Background

The lifetime risk of having herpes zoster is 20 to 30 percent, with 10 to 20 percent of the patients developing herpes zoster ophthalmicus.1 HZO may present with diverse ocular and central nervous system symptoms with 50 percent of patients having ophthalmic manifestations.1 HZO has caused extraocular muscle palsies of the third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves in 7 to 31 percent of patients and is usually a self-limiting condition.2 Optic neuritis and orbital involvement from HZO has been described.3-6 However, panuveitis and orbital disease in one patient is rare.

Diagnosis and Treatment

As initially described in 1965, HZO reactivation is largely dependent on depressed cellular immunity as is often the case in patients on immunosuppression therapy.1,7 Various ocular complications of the HZO may include inflammation in any part of the eye including blepharitis; keratoconjunctivitis; iritis; and scleritis as well as intraocular involvement of anterior uveitis and posterior uveitis involving the retina.8 Optic neuritis has been documented as well and may be bilateral even in unilateral HZO.5

|

Treatment of HZO is mainly antivirals. Combination of IV acyclovir as initial therapy in the acute phase and valacyclovir as an outpatient regimen can be often utilized. Tapering doses of oral prednisone in 60, 30 and 15 mg/day per week may be used as well in cases of severe pain, severe rash and cranial polyneuritis.14,15 Our patient’s condition significantly improved with oral antiviral alone in terms of visual acuity, motility and inflammation.

Without increased awareness of the disease, herpes virus often has protean presentations that may be misdiagnosed initially, as it was in this case.

Case Report

An 82-year-old retired nun with a history of dementia was referred for evaluation of right visual loss and ophthalmoplegia. The patient initially presented to an outside emergency department for altered mental status and was discharged to a short-term rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of worsened depression. During the admission, she was treated with topical and oral antibiotics for presumed right conjunctivitis. Two weeks later she was seen by an outside ophthalmologist and found to have right vision loss and ophthalmoplegia. She was referred to neuro-ophthalmology for further evaluation.

The patient complained of a gradual decrease in vision, redness and swelling of the right eye over one month. She also described a non-painful rash over her right eye, which preceded all other symptoms. Her systemic review of systems was otherwise negative. Pertinent medical history includes history of herpes zoster over the abdomen 10 years previously.

On examination, the patient was awake and alert. Best-corrected visual acuity was count finger at 3 feet in the right eye, and 20/30 in the left. Pupillary exam showed a dilated, poorly reactive right pupil with a relative afferent defect. Intraocular pressure was 24 mmHg in the right eye and 12 mmHg in the left. There was ophthalmoplegia with -3 restriction of supraduction, -2 abduction, -2 infraduction, and -4 adduction (See Figure 1).

|

The patient was admitted to the hospital and started on IV acyclovir (10 mg/kg), and topical prednisolone and cyclopentolate eye drops.

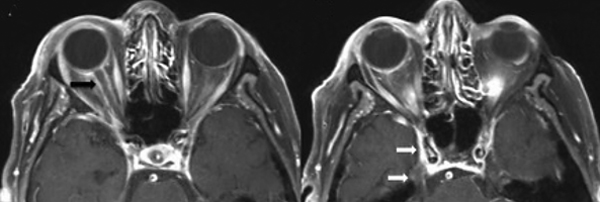

Laboratory evaluations for other infectious and inflammatory etiologies were negative. HIV status was not documented. A contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain and orbit showed right optic nerve sheath enhancement with intraconal inflammation and right trigeminal nerve enhancement of V1 and V2 distribution (See Figure 2).

After 48 hours of systemic therapy with acyclovir, the patient’s vision and orbital findings began to improve. On one week follow-up after discharge with oral acyclovir, the patient’s right visual acuity improved to 20/60 and intraocular pressure decreased to 18 mmHg without any ocular hypotensive therapy. Motility improved in all directions. Vitritis subsided to allow dilated fundus exam, which showed vitreous debris. The optic nerve appeared sharp and pink with no retinal involvement. REVIEW

The authors are at the Yale School of Medicine. Drs. Yun, Wong, Huang and Levin are in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences; Dr. Malhotra is in the Department of Neuroradiology.

1. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology 2008;115:S3-12.

2. Marsh RJ, Dulley B, Kelly V. External ocular motor palsies in ophthalmic zoster: A review. Br J Ophthalmol 1977;61:677-82.

3. Selbst RG, Selhorst JB, Harbison JW, Myer EC. Parainfectious optic neuritis. Report and review following varicella. Arch Neurol 1983;40:347-50.

4. Deane JS, Bibby K. Bilateral optic neuritis following herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:972-3.

5. Gunduz K, Ozdemir O. Bilateral retrobulbar neuritis following unilateral herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmologica 1994;208:61-4.

6. Wang AG, Liu JH, Hsu WM, Lee AF, Yen MY. Optic neuritis in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2000;44:550-4.

7. Hope-Simpson RE. The Nature of Herpes Zoster: A Long-term Study and a New Hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965 ;58:9-20.

8. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology 2008;115:S24-32.

9. Kurimoto T, Tonari M, Ishizaki N, et al. Orbital apex syndrome associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Clin Ophthalmol 2011;5:1603-8. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S25900. Epub 2011 Nov 9.

10. Saxena R, Phuljhele S, Aalok L, et al. A rare case of orbital apex syndrome with herpes zoster ophthalmicus in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Indian J Ophthalmol 2010;58:527-30.

11. Archambault P, Wise JS, Rosen J, Polomeno RC, Auger N. Herpes zoster ophthalmoplegia. Report of six cases. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1988;8:185-93.

12. Lexa FJ, Galetta SL, Yousem DM, Farber M, Oberholtzer JC, Atlas SW. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with orbital pseudotumor syndrome complicated by optic nerve infarction and cerebral granulomatous angiitis: MR-pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993;14:185-90.

13. Naumann G, Gass JD, Font RL. Histopathology of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am J Ophthalmol 1968;65:533-41.

14. Whitley RJ, Weiss H, Gnann JW Jr., et al. Acyclovir with and without prednisone for the treatment of herpes zoster. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:376-83.

15. Wood MJ, Johnson RW, McKendrick MW, Taylor J, Mandal BK, Crooks J. A randomized trial of acyclovir for 7 days or 21 days with and without prednisolone for treatment of acute herpes zoster. NEJM 1994;330:896-900.