When a patient with dry eye isn’t responding to treatment, it can be frustrating for the clinician and even more so for the patient experiencing discomfort. When you come across these cases, it’s important to thoroughly review the history, re-interview patients, perform additional testing and evaluate the possibility of underlying illness. A combination of factors could be responsible.

Here, cornea specialists offer guidance on troubleshooting stubborn ocular surface problems.

Confirm the Diagnosis

Only once you’re confident a patient has been properly diagnosed can you search for effective options to treat or manage their dry eye. When traditional treatment methods fail to relieve symptoms, the first step is to call the initial diagnosis into question. Ask yourself such questions as, “How was the initial diagnosis determined?” and “Do the patient’s past and current clinical signs, symptoms and treatment responses align with the diagnosis?”

|

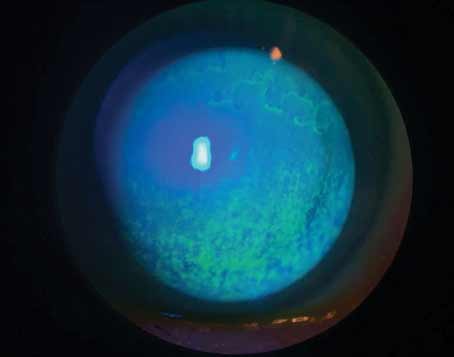

| Figure 1. Slit lamp image of a cornea with neurotrophic keratitis showing central corneal punctate erosions. This patient was misdiagnosed as having dry eye and treated with topical anti-inflammatories and lubricants without improvement. Corneal punctate erosions could be due to a number of ocular surface diseases, including dry eye. In this case, timely diagnosis and treatment using topical recombinant nerve growth factor would be appropriate. Photo: Esen Akpek, MD. |

Esen Akpek, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and director of the Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic at the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore, says, “You first need to define the patient’s dry eye. Have you confirmed that it’s nothing else but either aqueous or evaporative tear deficiency? There are many forms of ocular surface disease that may affect more than only tears, so there are a number of differentials that you need to consider,” she explains.

One thing that makes it challenging to identify the root cause of a patient’s dry eye is the overlap between signs and symptoms. “There’s no unique sign or symptom for any of the ocular surface diseases,” Dr. Akpek says. “Patients complain of itching, burning, blurry or fluctuating vision, stinging, foreign body sensation, etc., with any of these conditions, so symptoms don’t always help to identify the problem.

“Signs aren’t always helpful, either,” she continues. “There could be corneal staining in the presence of neurotrophic keratitis, for example (Figure 1). That’s not an inflammatory condition, neither is it caused by a tear-film or tear-production problem. Although it’s true that patients with NK don’t produce enough tears, the underlying problem is a neurotrophic state of the cornea, which may be a result of an injury or systemic condition like diabetes or multiple sclerosis.” In cases like this example, medical history may be more useful in conjunction with signs and symptoms to help inform the diagnosis and direct further testing or referral options.

Once you go back and review the patient’s case history, including comorbid conditions, surgical history and prescribed or over-the-counter medications, “perform another comprehensive exam paying attention to all the findings, including tear-film breakup time, tear osmolarity, inflammatory markers, corneal staining patterns, conjunctival staining, conjunctival topography, meibum quality and lid margins,” Dr. Akpek suggests. “This is key to reconfirm the patient’s initial diagnosis and determine whether there’s another or multiple other conditions that could be underlying the ocular surface disease.”

Let’s talk about some other conditions that might be at play.

Ocular Differentials

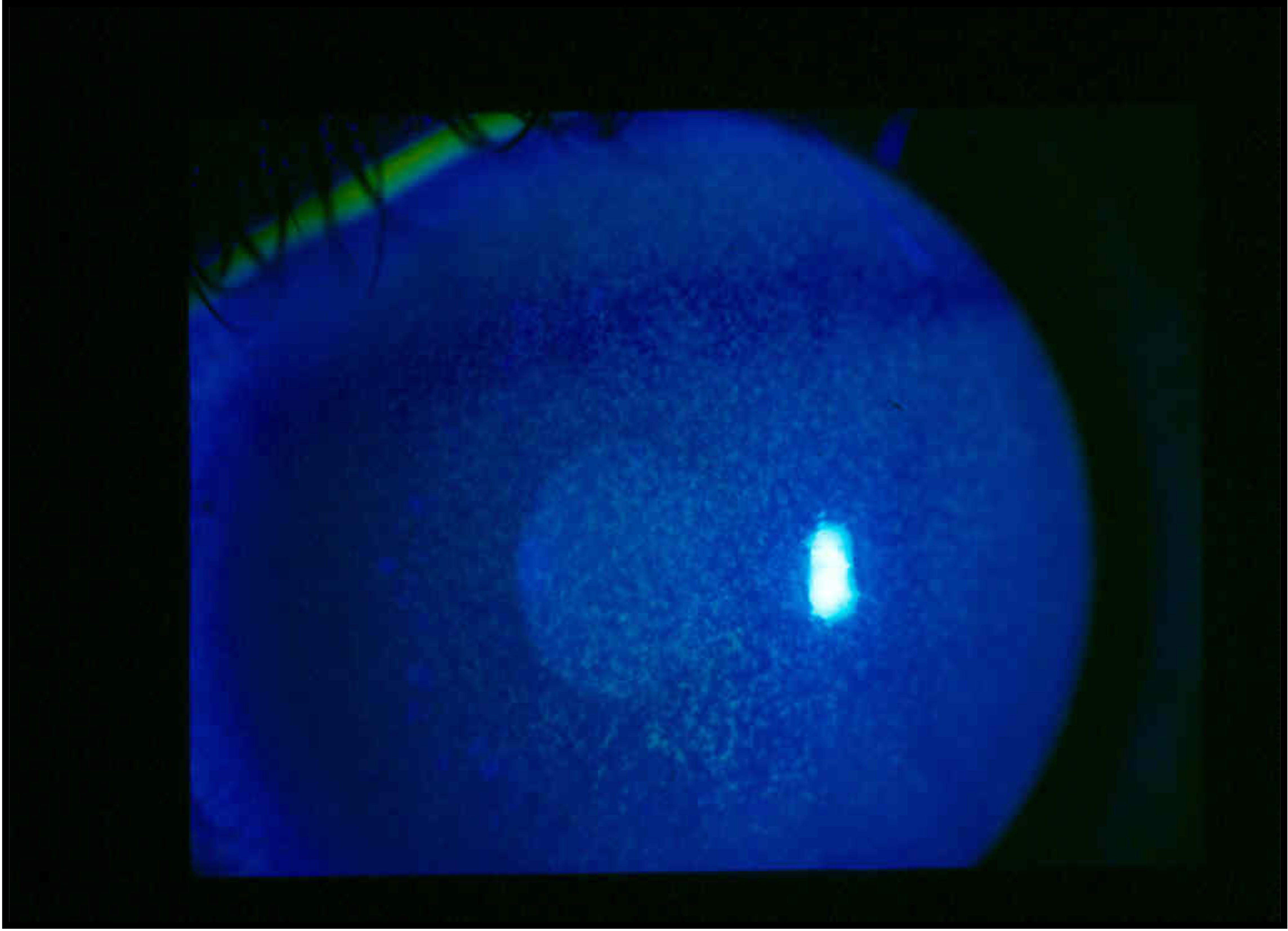

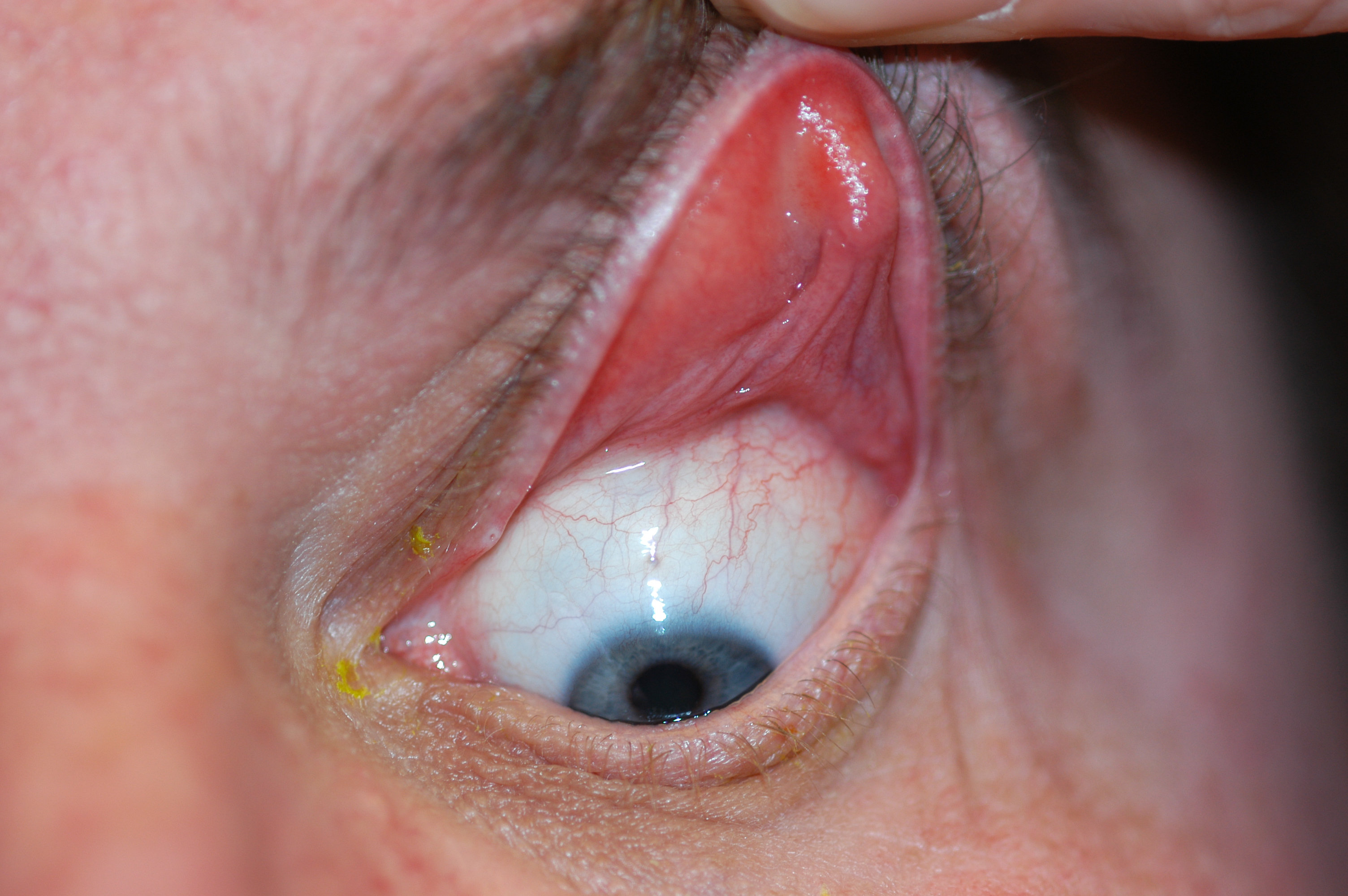

“If your patients aren’t responding to treatments for dry eye or blepharitis, you’re going to have to think outside the box a little,” says Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, Chief of Wills Eye Hospital’s Cornea Service. “Look behind the lids and ask yourself if you see signs of giant papillary conjunctivitis or severe allergy. When you flip the lid, is it very floppy? If it is, floppy eyelid syndrome may be causing some of their symptoms (Figure 2). There’s also a severe form of this condition called eyelid imbrication syndrome, where the upper lid is so loose that it sort of overrides the lower, and that can cause significant symptoms.” He adds that floppy eyelids are often associated with sleep apnea, and especially if patients snore at night, send them to their primary care physician who will likely perform a sleep study.

|

| Figure 2. This middle-aged man complaining of chronic dry and irritated eyes has severe floppy eyelid syndrome. He also has sleep apnea, which is not uncommon in patients with floppy lids. Photo: Christopher Rapuano, MD. |

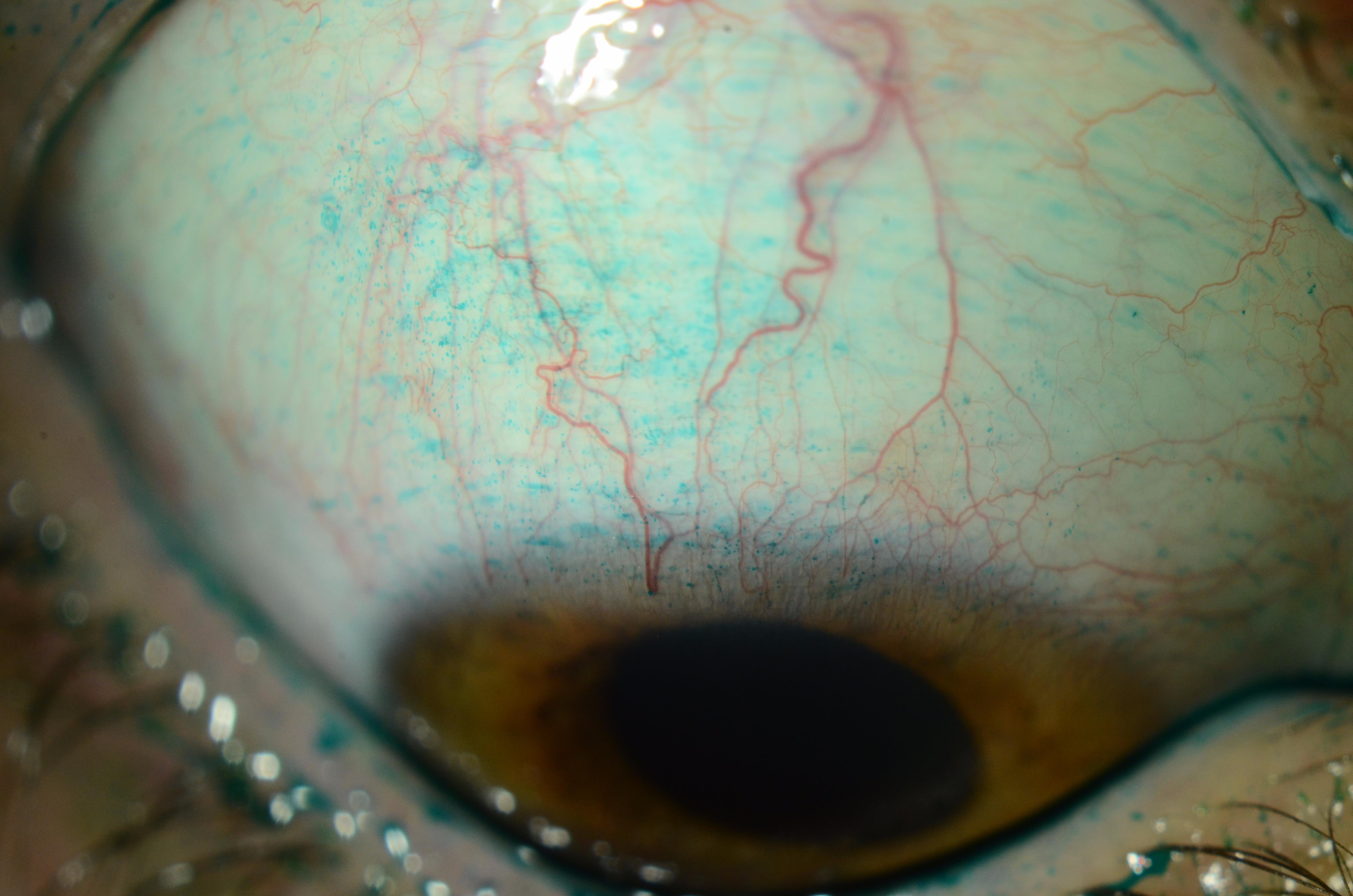

Another condition that Dr. Rapuano says is often missed is superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. “When you flip the lid and have the patient gaze down, look at the upper conjunctiva,” he explains. “If the patient has SLK, you may see thickening of the conjunctival tissue, and punctate erosions will be seen on the superior cornea, limbus and bulbar conjunctiva.”

Conjunctivochalasis is also an underappreciated differential diagnosis for dry eye. “With this condition, there’s excess conjunctiva usually rubbing against the lower lid,” Dr. Rapuano notes. He adds that conjunctivochalasis particularly affects older patients, as the conjunctiva becomes looser with age. “If you look at the lower lid margin and see excess conjunctival tissue, sometimes doing a little ‘tummy tuck’ and snipping the excess tissue can make patients’ symptoms a lot better,” he says.

Another condition to look out for particularly in older patients is mucous membrane pemphigoid. “When you have a patient look up and pull the eyelid down, you want to make sure you don’t observe any scarring of the inferior conjunctiva or forniceal foreshortening,” says Dr. Rapuano. “If the fornix is shortened, that can be an early sign of mucous membrane pemphigoid that’s often missed because clinicians don’t look for it, and by the time they find it, the patient’s symptoms are already severe.” He adds that if you suspect this condition in one of your patients, a biopsy must confirm the diagnosis, and it’s often treated with immunosuppressives.

To rule out incomplete lid closure, he suggests asking patients to close their eyes gently as if they’re sleeping. “You can also ask if their partner or family member has remarked that they sleep with their eyes partially open. That can lead to exposure and be causing the eyes to dry out at nighttime.” These patients can try to alleviate the problem using ointments, sleep masks or, in severe cases, eyelid surgery.

Although ocular cancer isn’t typically a concern in complex dry-eye cases, it is still a possibility to keep in mind. “If you notice very asymmetric blepharitis or asymmetric lid disease, consider performing a biopsy to check for sebaceous carcinoma,” notes Dr. Rapuano.

|

| Figure 3. This patient had seen several eyecare specialists with complaints of chronic foreign body sensation and discomfort with blinking. Upon downgaze, a slightly injected and thickened superior conjunctiva that stains with lissamine green dye can be seen. Photo: Christopher Rapuano, MD. |

Systemic Conditions

Besides eyelid and tear-film issues, it’s important to familiarize yourself with the various systemic conditions that can also lead to or mimic symptoms of dry eye. If your patient has a diagnosed or undiagnosed illness, treating their ocular symptoms will only put a Band-Aid over the core issue. Dr. Akpek says in cases like these, referring patients to a doctor specializing in their underlying condition is typically the best option.

Here are a few systemic diseases to consider when managing patients with persistent eye dryness.

• Diabetes. This is one common condition affecting the ocular surface that is often overlooked by eye doctors. “Diabetes is considered an epidemic today,” says Dr. Akpek. “Ophthalmologists, aside from those who work in retina, don’t pay enough attention to diabetes, which is a common cause of ocular surface disease, although it’s not a tear-film problem. If a patient has a family or personal history of diabetes and is dealing with dry eye, I might refer them to an endocrinologist to have their HbA1c level measured and discuss ways to get that value back into range, which, in turn, may improve their ocular symptoms,” she continues. “If there’s no history of diabetes but I suspect the patient might have it, I will refer them to their PCP.” Ocular signs that may point to diabetes include (characterized by decreased corneal sensation and decreased tear production in the absence of pain) and delayed ocular surface regeneration.

• Sjogren’s syndrome. Dry eye is a hallmark sign of this condition, which Dr. Akpek argues is “severely underappreciated, underdiagnosed and undertreated.” When dry eye is accompanied by dry mouth, consider this autoimmune disease a differential. “Depending on symptom severity, I will either send these patients to their PCP or a rheumatologist,” says Dr. Rapuano.

• Thyroid eye disease. Also known as Graves’ disease, “TED is a common and undiagnosed autoimmune disease,” says Dr. Akpek. “It’s not always obvious; it could be occult. Patients might have had it for a while but didn’t know, and they may have eye problems because of it.” TED may cause a range of ocular symptoms, including eye bulging, gritty sensation, pressure or pain, puffy eyelids and visual problems such as light sensitivity, double vision or vision loss. Dr. Rapuano says that at Wills Eye, “exposure keratitis is probably the number one thing that we see with Graves’.”

If you suspect TED, Dr. Akpek recommends ordering an MRI or ultrasound to observe the ocular muscles and determine whether inflammation is present, as well as “check anti-thyroid antibodies to see if the problem is still active subacutely.” She adds, “if the patient is hypo- or hyperthyroid, I’d refer them to an endocrinologist, but it’s our job to treat the inflammation.” Drop therapy, in combination with systemic treatments, should help to alleviate the patient’s symptoms, Dr. Akpek suggests. There’s also a fairly new treatment for TED that became FDA-approved in 2020—Tepezza (teprotumumab-trbw)—which Dr. Rapuano says “could help with the bulging and decrease some of their redness and dry-eye symptoms.”

• Other autoimmune conditions. “There are approximately 1.5 million individuals in the United States with rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Akpek says. “These patients have already been diagnosed by a rheumatologist 98 percent of the time, but they might be undertreated. The same goes for lupus patients. Most already have a diagnosis and are taking medication, but they still may have ocular symptoms, which might call for escalation of treatment for dry eye.”

Keep in mind that patients with autoimmune diseases often have more than one. For example, it’s not uncommon for patients with Sjogren’s to also have rheumatoid arthritis or lupus. Work with the patient’s rheumatologist if you feel that further testing may be needed. Dry-eye symptoms may improve once underlying diseases and comorbidities receive proper intervention.

Additional Considerations

Medication use and history of ocular surgery could also help explain why a patient’s dry-eye symptoms aren’t responding to treatment. Here’s why.

Medications. There are dozens of medications that can cause dry eye. Here are a few:

- painkillers;

- topical and oral antibiotics;

- antihistamines;

- antidepressants;

- certain heart and blood pressure medications;

- diuretics;

- birth control/hormones;

- ulcer medications; and

- cancer medications.

“Sometimes, patients are on so many kinds of drugs—painkillers, antidepressants, diuretics for blood pressure and so on—that you can’t adequately address the dry-eye symptoms or eye structure,” Dr. Akpek points out. “But, once they discover that one or multiple of these medications may be causing or contributing to their discomfort, they might be willing to discontinue some or decrease the dosage where they can,” she says.

If you infer a patient’s medication could be causing their dry eye, Dr. Rapuano also suggests “contacting the prescribing doctor to see whether there are other medications that might work just as well without the side effect. In either case, your job is to treat the patient’s ocular symptoms.”

Past ocular procedures. “Some patients who’ve had corneal surgery like LASIK or PRK may have neuropathic pain along with dry eye,” says Dr. Rapuano. “In this case, the nerves have been damaged, causing hypersensitivity, which is a much more difficult entity to treat. Some neuropathic pain medications such as Lyrica (pregabalin) or Neurontin (gabapentin) might be able to help,” he suggests.

Eyelid surgery such as blepharoplasty can also cause eye dryness from exposure, Dr. Rapuano explains. “After the lid is lifted, the eye may not close very well. I have a lot of patients who have exposure keratitis from blepharoplasty, and it may take me a while to figure that out because they either forgot or don’t want to admit it,” he notes.

Ultimately, to help narrow down differentials in stubborn dry-eye cases, Dr. Akpek says, “Ask questions and evaluate the ocular surface as a whole. It’s usually not just dry eye, but a number of different things causing the patient’s symptoms.”

Dr. Akpek is a consultant for Novalique and Dompé and an investigator for Ocular Therapeutix. Dr. Rapuano is a consultant for Bio-Tissue, Dompé, Glaukos, Kala, Oyster Point, Sun Ophthalmics, Tarsus and TearLab.