For years, the treatment paradigm for patients with diabetic retinopathy was fairly well-established. Recently, however, the advent of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections and data from studies are changing some treatment patterns. Here’s a review of how retina specialists currently approach these patients, after taking into account all of the recent developments.

Treatment Philosophy

Treatment for nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy depends on severity. Assuming there’s no diabetic macular edema, most cases of mild NPDR can be observed. More advanced cases-—moderately severe to severe NPDR—can be considered for treatment, which typically includes intravitreal injection or laser photocoagulation.

|

|

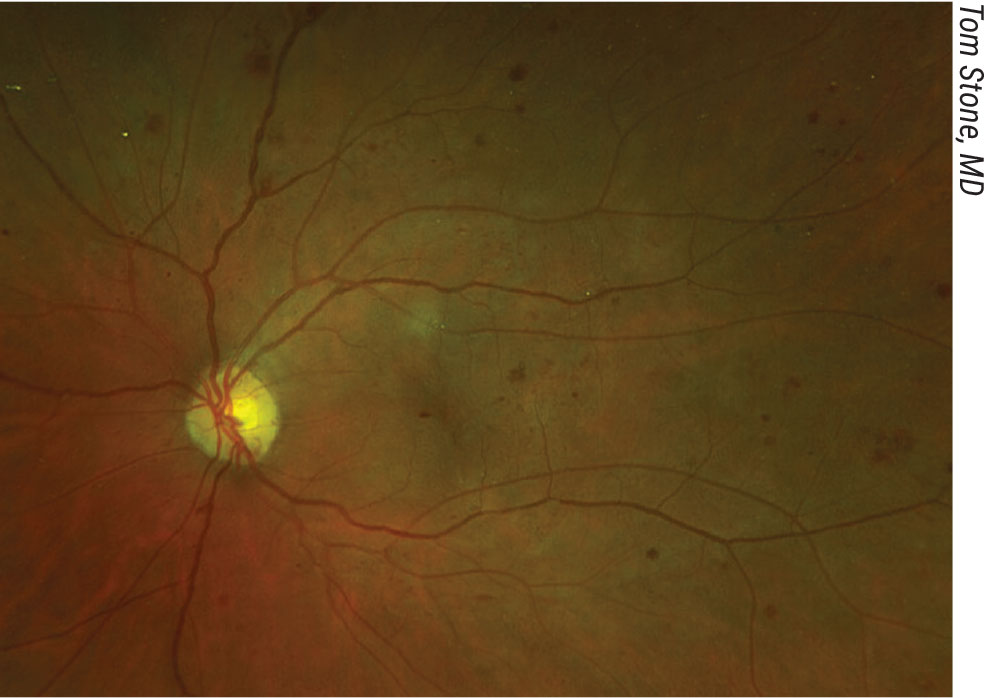

Severe NPDR in a patient with significant peripheral nonperfusion on fluorescein angiography. Click image to enlarge. |

Whether to use injection or laser, as well as the length of treatment, is up for debate. “Obviously, if you ask 10 retina specialists, I’m sure you’ll get different answers,” says Tom Stone, MD, who practices in Lexington, Kentucky. “For me, it depends on the underlying condition of the patient. If someone has kidney disease, hypertension, or if he or she smokes or is obese, these conditions will further compound the care of NPDR. I would consider anti-VEGF therapy in these patients. In other patients who have mild cases, I will just watch them and try to coordinate with their primary care physician to optimize their systemic status.”

Chicago’s Jennifer Lim, MD, agrees that patients with mild cases of NPDR shouldn’t be treated unless there is clinically significant edema. “This can happen in any category of diabetic retinopathy, and we make decisions based upon the location of the edema,” she says. “The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Retina Network Protocol V results1 say that if vision is 20/20 or 20/25, patients can just be watched for worsening in terms of vision loss or thickening. If worsening occurs, then we’ll institute treatment. However, if patients are mild and there’s no macular edema, we typically just follow them. If it’s very mild, I’ll see them once a year and just educate them about the symptoms of macular edema, such as distortion, decreased vision or developing neovascularization. It would be rare for a patient with mild NPDR without edema to develop NPDR progression within a year. We also recommend good control of glucose, blood pressure and cholesterol. I advise my patients to have a hemoglobin A1C goal of 7 or below. I also remind patients with renal issues that renal control also affects macular edema. I think those factors are really key to systemic control in these patients.”

A recent study confirmed the use of observation-only for mild cases of NPDR.1 The study compared vision loss at two years among eyes initially managed with aflibercept, laser photocoagulation or observation and found that, among eyes with center-involved DME and good visual acuity, there was no significant difference in vision loss at two years between the three groups. The researchers concluded that observation without treatment, unless visual acuity worsens, may be a reasonable strategy for center-involved DME.

This randomized clinical trial was conducted at 91 sites in the United States and Canada and included 702 adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. All participants had one study eye with center-involved DME and visual acuity of 20/25 or better. Participants’ mean age was 59 years, and 62 percent were men.

All eyes were randomly assigned to one of three groups: 226 eyes received 2 mg of intravitreous aflibercept as frequently as every four weeks; 240 eyes received focal/grid laser photocoagulation; and 236 eyes were observed. Aflibercept was required for eyes in the laser photocoagulation or observation groups that had decreased visual acuity from baseline of at least 10 letters at any visit, or a loss of five to nine letters (one to two lines) at two consecutive visits.

Of the original 702 randomized participants, 625 completed the two-year visit. For eyes with visual acuity that decreased from baseline, aflibercept was initiated in 25 percent of the laser photocoagulation group and in 34 percent of the observation group. At two years, the percentage of eyes with at least a five-letter visual acuity decrease was 16 percent in the aflibercept group, 17 percent in the laser group and 19 percent in the observation group. There was no significant difference in vision loss between groups.

Moderately Severe and Severe Cases

Even in cases without diabetic macular edema, moderately severe to severe cases of diabetic retinopathy always require treatment.

The PANORAMA study found that intravitreal aflibercept injection improved diabetic retinopathy and prevented disease progression in eyes with moderately severe to severe NPDR, in patients without DME.2

Patients were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years of age and had type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus and moderately severe to severe NPDR, absence of center-involved DME, and baseline best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better in the study eye. A total of 402 eyes were randomized to three groups: 135 received intravitreal aflibercept injection (IAI) 2 mg every 16 weeks (2q16) after three monthly doses vs. one dose at an eight-week interval; 134 received IAI 2 mg every eight weeks (2q8) after five monthly doses; and 133 eyes received sham. The primary endpoint was the proportion of eyes with at least a two-step improvement in DRSS score at week 52. Data were analyzed to determine the visual and anatomic outcomes at 100 weeks.

Two-thirds (66 percent) of the patients were men, and participants had a mean age of 55.7 years. The mean baseline BCVA score was 82.4 ±6.0 letters. At week 52, 65 percent of the 2q16 eyes and 80 percent of the 2q8 eyes had at least a two-step improvement in DRSS score, compared to 15 percent of sham eyes. Additionally, 9 percent of 2q16 eyes and 15 percent of 2q8 eyes had at least a three-step improvement in DRSS score, compared to less than 1 percent of sham eyes.

Through week 52, 4 percent of 2q16 eyes and 3 percent of 2q8 eyes developed a vision-threatening complication, compared with 20 percent of sham eyes. IAI significantly reduced the risk of developing a vision-threatening complication, by 85 percent in the 2q16 group and 88 percent in the 2q8 group compared to sham. The incidence of center-involved DME was lower in the 2q16 (7 percent) and 2q8 (8 percent) groups compared with the sham group (26 percent). Additionally, IAI significantly reduced the risk of developing center-involved DME, by 79 percent in the 2q16 group and by 73 percent in the 2q8 group.

David S. Boyer, MD, who is in practice in Los Angeles, says that this study provided a good indication of the value of anti-VEGF therapy for the treatment of high-risk NPDR without diabetic macular edema as a means to prevent further visual loss and severe vision-threatening complications. “Prior to that, we knew that diabetic retinopathy severity improves with anti-VEGF therapy, but we really didn’t have a great way of following patients, or some type of cookbook that we could use. This trial really gave us a foundation regarding what to do,” he says.

|

However, he notes that compliance with routine injection schedules can be difficult to maintain. “We all know that diabetic patients who have severe NPDR may have other medical conditions that don’t allow them to come back as scheduled for these injections. In addition, diabetic patients may lose their insurance and not be able to return for that reason. In cases where we use anti-VEGF and then stop, patients worsen. So, you need a very cooperative and compliant patient to institute anti-VEGF alone. In these cases, laser treatment has an advantage. If you stop treating with a laser, you will get some progression of the retinopathy, but you may not get the devastating loss of vision that you would get by stopping anti-VEGF therapy,” Dr. Boyer explains.

He adds that he is currently treating patients with both anti-VEGF injection and laser. “I might treat the periphery, those areas adjacent to severe non-perfusion, with laser,” he says. “I’m using less laser than I was previously, and I’m using anti-VEGF in combination with it to make sure that I’m keeping the eye under control, because laser treatment can institute some degree of macular edema. So, many times, I’ll use a combination of both entities. Once I feel comfortable that, even if the patient didn’t return, he or she won’t develop rubeosis or the eye feels stable, I may follow the patient and treat every three to four months to prevent the development of vitreous hemorrhage and other high-risk complications.”

How Long to Treat?

Dr. Boyer notes that one reason ophthalmologists are hesitant to institute anti-VEGF therapy is that they don’t know when to stop. “Do we treat every four months for the rest of the patient’s life? Do we get to a certain point where we can stop, and the clock resets, and we can watch them for a while?” he muses. “If a patient presents with an A1C of 9 or higher, I know the patient’s not going to be able to come in as often he or she needs to. This patient will get other side effects, including kidney disease. I’m more likely to treat that patient aggressively with a laser to prevent him or her from experiencing further vision loss, because the patient may not come back. On the other hand, if a patient has an A1C of 6.5 or 7 and has improved the quality of diabetic control, I might consider treating those cases with anti-VEGF, but, again, we don’t know the endpoint.”

Dr. Lim follows patients with moderate NPDR every four to six months, depending on the severity. For severe NPDR, she typically follows patients every three to four months, again depending on severity. “There’s mild, moderate and then there’s more severe moderate,” she says. “Similarly, for severe, there’s moderately severe, and then there’s very severe. Generally, the more severe it is, the more often we see them. The PANORAMA study did show benefits for eyes with moderate NPDR to severe NPDR, in terms of limiting the progression of retinopathy and preventing complications such as anterior segment neovascularization, center-involving DME and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The reductions are significant—60-percent to 79-percent reductions in what would have happened otherwise over the course of time. When I look at a patient and I’m trying to decide whether to start him or her on anti-VEGF, I have to take into account the patient’s risk of complications, the risk of the injection itself, the cost of the drug and the societal cost of having the patient taking off work or having someone else take off work if the patient is incapable of coming in on his or her own.”

Dr. Lim adds that the patient must be willing to return for the series of injections. “Otherwise, he or she won’t get the same benefit that we experienced in the PANORAMA clinical trial, and we saw some pretty amazing results,” she says. “So, if I have a partnership with the patient, the patient agrees to come in for multiple injections, the patient knows and accepts the risks, and the patient is willing to undergo treatment, then we’ll go ahead and do it. However, this doesn’t happen often. It’s hard to convince patients to get a treatment when they have no symptoms and there’s a downside in terms of risk of infection. However, if they can see that their disease is progressing from moderately severe to severe, they may agree to start therapy.”

The Future

Dr. Lim believes that the use of lasers in the future will be limited mostly to PDR. “You’re basically scarring the patient’s retina,” she says. “Although there’s essentially no risk of endophthalmitis with the laser, I prefer not to create retinal scars. In some patients, depending on the degree of pigmentation in their retinal pigment epithelium, the laser scars can expand with time. The more energy you use and the more pigmentation the patient has, the more scarring will occur. I would rather inject an anti-VEGF in patients with early PDR. If there is early proliferative retinopathy and the patient is reliable, we can choose an anti-VEGF instead of laser. I would definitely not use laser for severe NPDR. I reserve its use for moderate to advanced PDR and also for preoperative use in patients who have traction retinal detachments and active PDR.”

Dr. Stone says that the only time he’d start with laser is if the patient has proliferative disease in one eye that’s been hard to control, and if he’s concerned that the patient won’t return for subsequent injections. “In these cases, I’ll preemptively do laser,” he says.

Dr. Boyer has consulting relationships with Alcon, Bausch + Lomb (Valeant), Bayer, Chengdu Kanghong Biotechnology, Genentech, Novartis Ophthalmics and Regeneron. Dr. Stone consults for Regeneron and Genentech. Dr. Lim consults for Genentech, Regeneron, Alcon and Chengdu.

1. Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:19:1880-1894.

2. Lim JI. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: Year 2 results from the PANORAMA study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2020;61:7:1381.