Today, cataract surgeons have more options than ever. They have multiple ways of making a capsulotomy, attacking the nucleus and even controlling miosis during surgery. The results of this year’s cataract surgery survey may give you a clearer picture of how some of your colleagues are adopting these new methods. This year, for example, a slightly higher percentage of surgeons than in previous years say they’re giving femtosecond a try; some are still hesitant to dive into intraoperative wavefront aberrometry; and quadrant division is the preferred way to break up a cataract.

These are just some of the results from this year’s survey on cataract surgery. This month, 2,001 surgeons of the 12,509 who received the survey opened it (16 percent open rate) and, of those, 110 fully completed the survey. To see how your preferences jibe with theirs, read on.

Femto Use Creeps Up

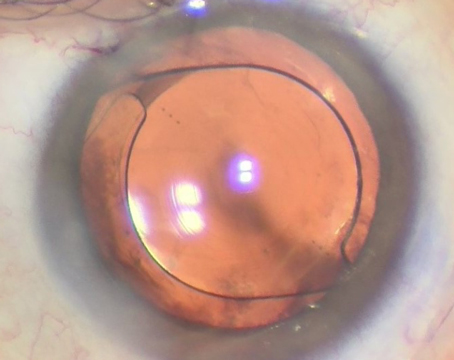

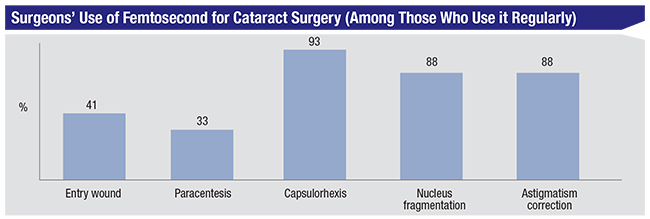

This year, a slightly higher percentage of respondents said they use the femtosecond laser for some phase of their cataract surgeries. Thirty-nine percent of the surgeons say they use the femtosecond (up from last year’s 36 percent), and 1 percent (one surgeon) says he uses the Zepto capsulotomy device. Among the femto users, it’s used most commonly to create the capsulorhexis (chosen by 37 percent). The popularity of its other uses appears in the graph on the facing page. The surgeons who use this technology say they appreciate the precision, and its usefulness in certain cases.

A surgeon from Pennsylvania lists what he likes about the technology: “Lower phaco energy, great astigmatism correction (especially with-the-rule) and a good patient experience,” he says. An ophthalmologist from Louisiana agrees, saying, “Femto is safer, creates a more precise capsulotomy and allows the management of mild astigmatism. Femto is essential for a very dense nuclear sclerotic cataract and I will use it in 100 percent of these cases, regardless of reimbursement.”

Kerry Hunt, MD, of Raleigh, North Carolina, says he thinks the femto is most useful in complicated cases. “I do like the ‘perfect’ capsulorhexis but I don’t need it for that,” he says. “Fragmentation is not possible in the most difficult cases where it would ideally be the most helpful. I think it’s greatest utility is in the setting of zonulopathy to get a good rhexis.”

Other surgeons are less impressed by femtosecond technology, for a variety of reasons, including the high cost.

“It’s useful for capsulorhexis for mature white cataracts,” says a New York surgeon. “Otherwise I do not find it valuable as compared to my standard technique. Time and expense are significant issues as well.” William E. Holcomb, MD, from Cullman, Alabama, needs to see more data. “There is no peer-reviewed evidence showing that either device improves clinical outcomes vs. a procedure performed by a good, experienced cataract surgeon,” he says. A surgeon from Oregon feels similarly. “Femtosecond cataract surgery and Zepto are solutions looking for a problem,” he says. “[It’s] more expense to be borne by the ambulatory surgery center and the patient without demonstrable benefit.”

|

“I have performed [femtosecond cataract surgery] in the past but no longer do it,” says a surgeon from Missouri. “I found it cumbersome. Positioning of the incisions was problematic at times. I also had two episodes of posterior capsule rupture due to gas buildup behind the cataract.”

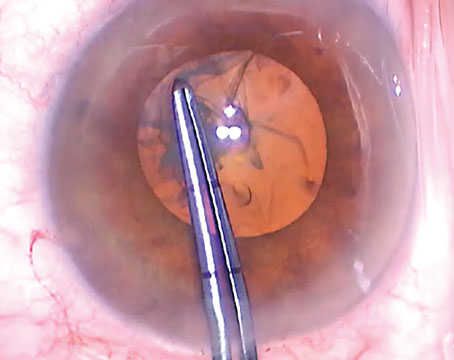

Breaking up the Nucleus

One of the primary areas where the art and science of cataract surgery come together is in the fragmentation of the nucleus. Many surgeons have their own particular way of attacking it that they feel works best for them.

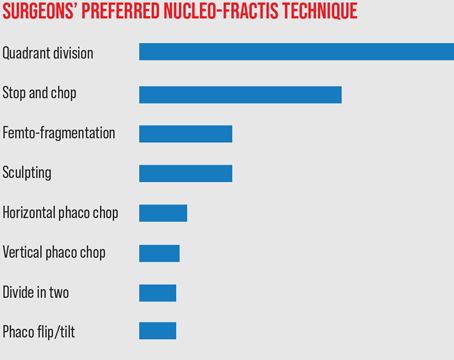

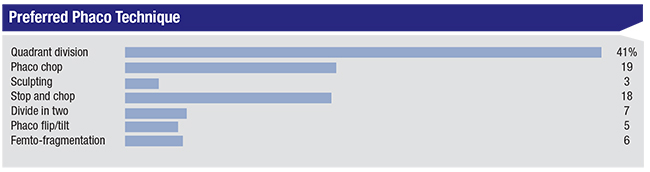

On this year’s survey, the most popular nucleo-fracture technique was quadrant division, chosen by 41 percent of the respondents. The next two most popular techniques were phaco chop (19 percent) and stop-and-chop (18 percent). All of the techniques chosen appear in the graph on p. 48.

“It’s simple, and I can use it on all grades of cataracts,” says a quadrant-division proponent from New Jersey. Alan Baribeau, MD, a surgeon from San Antonio, also likes the mechanical benefits of the technique: “It controls the fraction and phaco-ing best for the wide range of cataracts I have in my practice,” he says.

Several surgeons like the safety of quadrant division. “It works very well without passing instruments posterior to the lens equator,” an Arizona surgeon avers. “It puts less stress on the capsule zonules,” adds a doctor from Ohio.

Surgeons who prefer phaco chop say they use it because it minimizes the phaco power used in the eye.

“[I like] the speed of the nucleus disassembly and low ultrasound energy into the eye,” says Ivan Mac, MD, Charlotte, North Carolina, who uses phaco chop. A surgeon from Utah is thinking along the same lines: “It allows almost all the ultrasound to be expended at the iris plane or below, and wastes no energy with unnecessary, inefficient sculpting,” she says. “One can adjust fragment size to density. I prefer cross-action vertical chop with circumferential disassembly for brunescent nuclei.”

|

“Phaco chop allows me to perform my cases with minimal phaco energy and minimal stress on the cornea,” says Robert Bullington Jr., MD, of Phoenix.

Ben Hasty, MD, of Panama City, Florida, details his technique: “Phaco chop works in soft and hard lenses, and uses familiar tools, with the Seibel chopper already used as a ‘finger.’ ”

For the stop-and-chop adherents, the safety and stability of the technique are important to them.

“Debulking the nucleus with the central trough decreases overall cumulative dispersed energy, and helps protect the endothelium by allowing better control of chopped pieces,” says Alabama’s Dr. Holcomb. A Connecticut surgeon agrees, saying, “It’s easiest to perform efficiently with little energy.”

“I like to see the tip of the instrument at all times,” says an Illinois ophthalmologist. “I cannot do that with horizontal chop.”

|

Tackling Cylinder

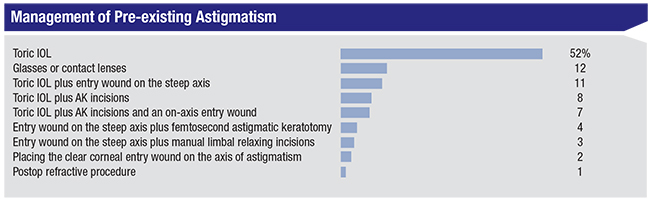

As in previous years, the most popular way surgeons correct asigmatism is with toric intraocular lenses, chosen by 52 percent of the respondents (53 percent in 2018). The second most popular choice was glasses and contact lenses (12 percent), followed by the combination of a toric IOL and the entry wound on the steep axis (11 percent). The full range of options selected by surgeons appear in the graph on p. 47.

A Pennsylvania surgeon likes the toric IOL’s predictability in certain cases. “It’s most predictable for moderate or severe astigmatism,” he says. “I generally use femto [AK] for mild astigmatism.” Eileen Wayne, MD, Moline, Illinois, agrees that “it’s very accurate.” Gregory Cox, MD, of Hamilton, New Jersey, calls toric IOLs “accurate and predictable.”

“The toric IOL is safe, reliable and predictable,” says Dr. Holcomb. “I’ll use it if the preop keratometric cylinder is 0.75 D or greater against-the-rule, or 1.25 D or greater with-the-rule.” Greensboro, North Carolina, surgeon Karl Stonecipher also shares his protocol: “For 0.75 D or less I do on-axis incisions and laser astigmatic incisions,” he says. “For 1 D or more I do toric IOLs.”

“I have generally seen very good to excellent results using this technology,” says Phoenix’s Dr. Bullington.

As for the tried-and-true options of spectacles and contact lenses, surgeons say it’s usually a matter of price. “Patients don’t want to pay for a toric lens,” says Christopher Papp, MD, of South Lyon, Michigan, who adds that he does provide toric lenses and limbal relaxing incisions for some patients who, presumably, are willing to pay for them.

Items of Interest

Surgeons also weighed in on other aspects of surgery, such as intraoperative wavefront aberrometry and maintaining an adequately sized pupil.

• Intraoperative aberrometry. On the survey, a third of the respondents use this technology to help select an IOL, with 11 percent deeming it excellent, 13 percent saying it’s good, 8 percent calling it fair and 0.9 percent (one surgeon) saying that it’s poor.

“This technology provides IOL power verification for post-refractive patients and adds confidence to my decision-making when choosing premium IOLs,” says a surgeon from Missouri.

Dr. Mac says he’s seen an improvement in his results. “I have objective clinical data that proves an improvement in my refractive clinical outcomes,” he says.

For the surgeons who only rate it as fair, they say it hasn’t separated itself from conventional methods.

|

“It hasn’t proven to be superior to calculations from the ASCRS website in my patients,” says Raleigh’s Dr. Hunt. “I use it only in post-refractive cases to avoid big errors.” A surgeon from Utah agrees, saying, “Most of the time there is very little value [to the technology]. The in-office measurements are good. It is beneficial in post-refractive cases [however].”

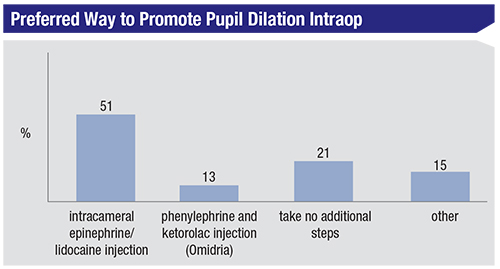

• Pupil dilation. Fifty-one percent of surgeons say they use a mixture of epinephrine and lidocaine, injected intracamerally; 21 percent take no additional steps; 13 percent use Omidria (Omeros, Seattle); and 15 percent use another method of pupil management (including phenylephrine/lidocaine injections, Malyugin rings and epinephrine in the irrigation bottle).

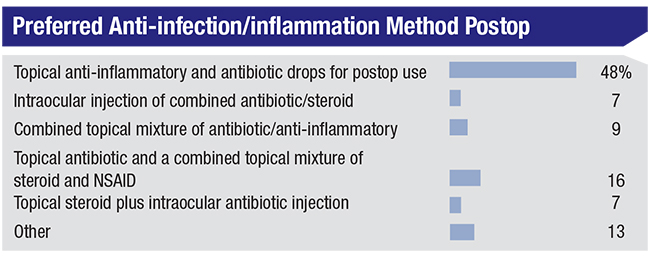

• Infection/inflammation prophylaxis. Here, the most popular answer was the conventional use of a topical anti-inflammatory and antibiotic postop (48 percent), followed by the use of a topical antibiotic and a combined topical mixture of a steroid and an NSAID (16 percent). Thirteen percent use another method (usually some permutation of intracameral drug combined with a topical drug or mixture postop). Nine percent use a combined mixture of antibiotics and anti-inflammatories, and 7 percent inject a combined antibiotic/steroid. The respondents’ answers appear in the graph above.

|

Surgical Pearls

The surgeons also provided their number-one piece of advice.

“Have the patient’s head in exactly the right position for their particular orbital/lid/head/neck configuration before ever touching the eye,” recommends Dr. Holcomb. A surgeon from Utah shares a safety tip: “Don’t allow the chamber to bounce around, and prevent both collapse and over-deepening,” she says.

A couple of surgeons have thoughts on the removal of cortex: “Remove subincisional cortex first during I/A before proceeding to other areas of cortex,” says a Pennsylvania ophthalmologist. And Jeff Whitman, MD, of Dallas, advises, “Irrigate/aspirate cortex centripetally—not with radial pulling.”

Though there are many techniques a surgeon can use, a doctor from New York says it’s better to simplify. “Learn a technique. Perfect it,” he says. “Your patients will be happy—and so will you!” REVIEW