No matter how you look at it, physician burnout has become an epidemic—and one with serious consequences. Not only does it rob doctors of the pleasure they might expect to derive from being a physician, it undercuts patient care; it’s contributing to doctors abandoning the profession, while the number of patients keeps increasing; and it’s contributing to an alarming increase in physician suicide. Leaving matters as they are isn’t an option; physician burnout is becoming more widespread every year.

|

To help get a handle on this epidemic, three professionals who have devoted significant time and effort to dealing with this crisis share what they’ve learned about 1) the causes of burnout—which may extend beyond the obvious culprits; 2) recognizing that you’re not simply tired—you’re in trouble; and 3) specific steps you can take to prevent burnout from derailing your life and career.

The Root of the Problem

Susan E. Connolly, MD, who practices at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, a large multispecialty medical group in northern California that employs more than 1,500 physicians, says she became interested in the subject of physician burnout when she realized that the phenomenon was becoming an epidemic—both across the country and in her own organization. (Dr. Connolly is an active member of the organization’s physician wellbeing committee, and she’s spoken on the topic of physician burnout at the past two meetings of the American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

|

“Over the past five to seven years, more and more physicians in our organization started showing symptoms of burnout,” she explains. “Doctors were complaining about the changing nature of the job and cutting back their hours. Physicians who used to talk enthusiastically about their work stopped doing so. Doctors began retiring early or leaving medicine. Never in my career had I seen such a mass exodus from the profession.

“It’s no secret that a big part of why we’re all burned out is because of the way American medicine and technology have evolved,” she says. “Technology in medicine, for example, has been sort of an evil rather than a benefit. Our medical records are now computerized, so we wind up typing the whole time we’re with a patient instead of making eye contact the way we would have in the past.

“That’s piled on top of other stresses,” she continues. “We have to fulfill countless requirements just to be reimbursed. We spend a lot of time trying to convince insurance companies that medicines or other treatments we recommend are truly best for our patients, even though they may be more expensive than what the insurance company wants to cover. Essentially, we’re doing the opposite of what we intended to do when we entered the profession. I think that’s why physicians are more burned out than most other professions.”

Dr. Connolly says she decided to join her organization’s wellbeing committee because she had some ideas she thought might help alleviate the situation. “One of the first things we did was to formally study physician burnout in our organization,” she says. “We created a one-page survey that we distributed to about 1,000 of our physicians. We discovered many factors that are associated with increased levels of burnout, including having less control over your work schedule and work environment; spending more hours documenting data on the computer; and feeling undervalued and underappreciated. We also found higher levels of burnout associated with female gender, and with holding leadership positions within the organization.”

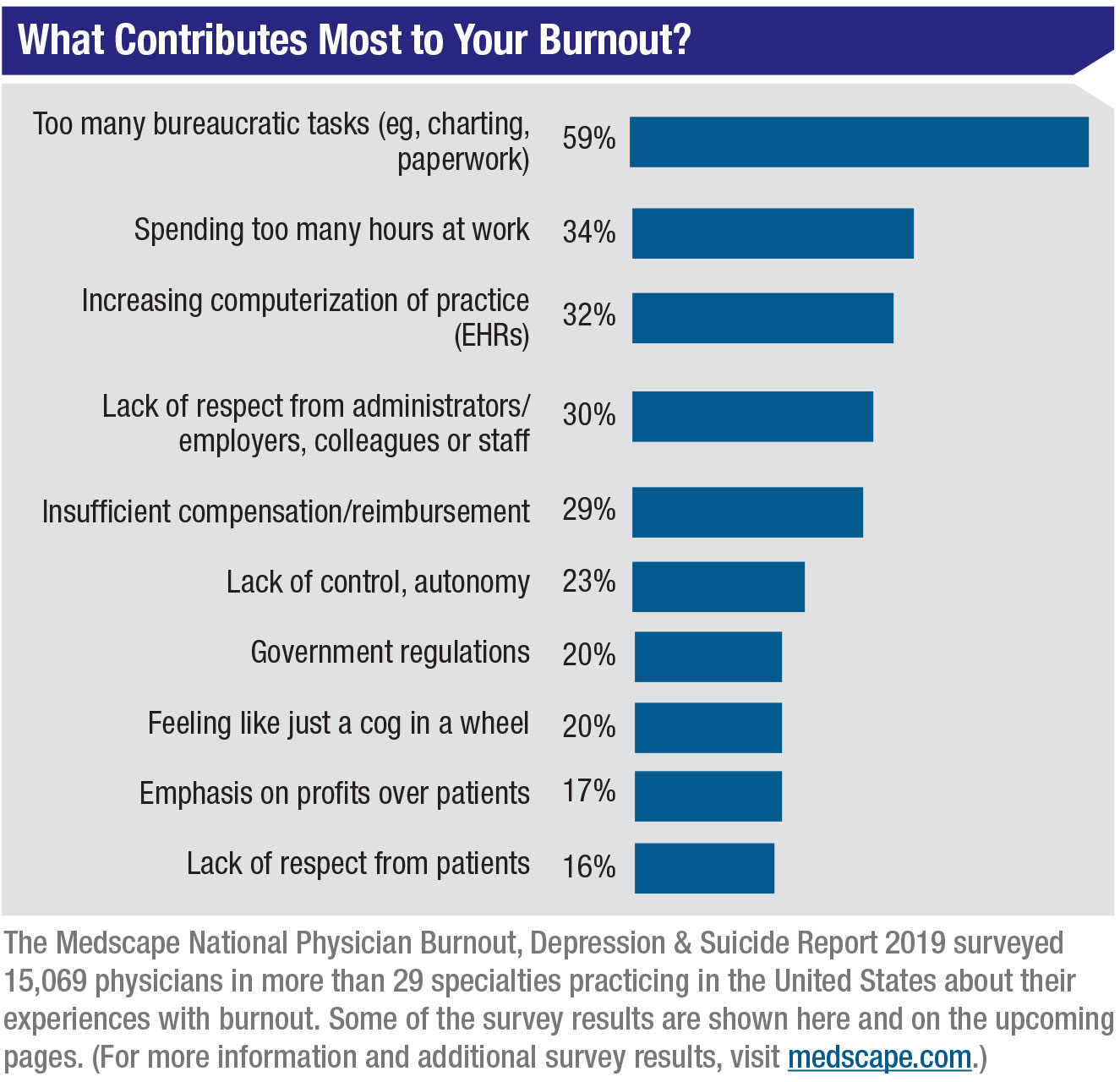

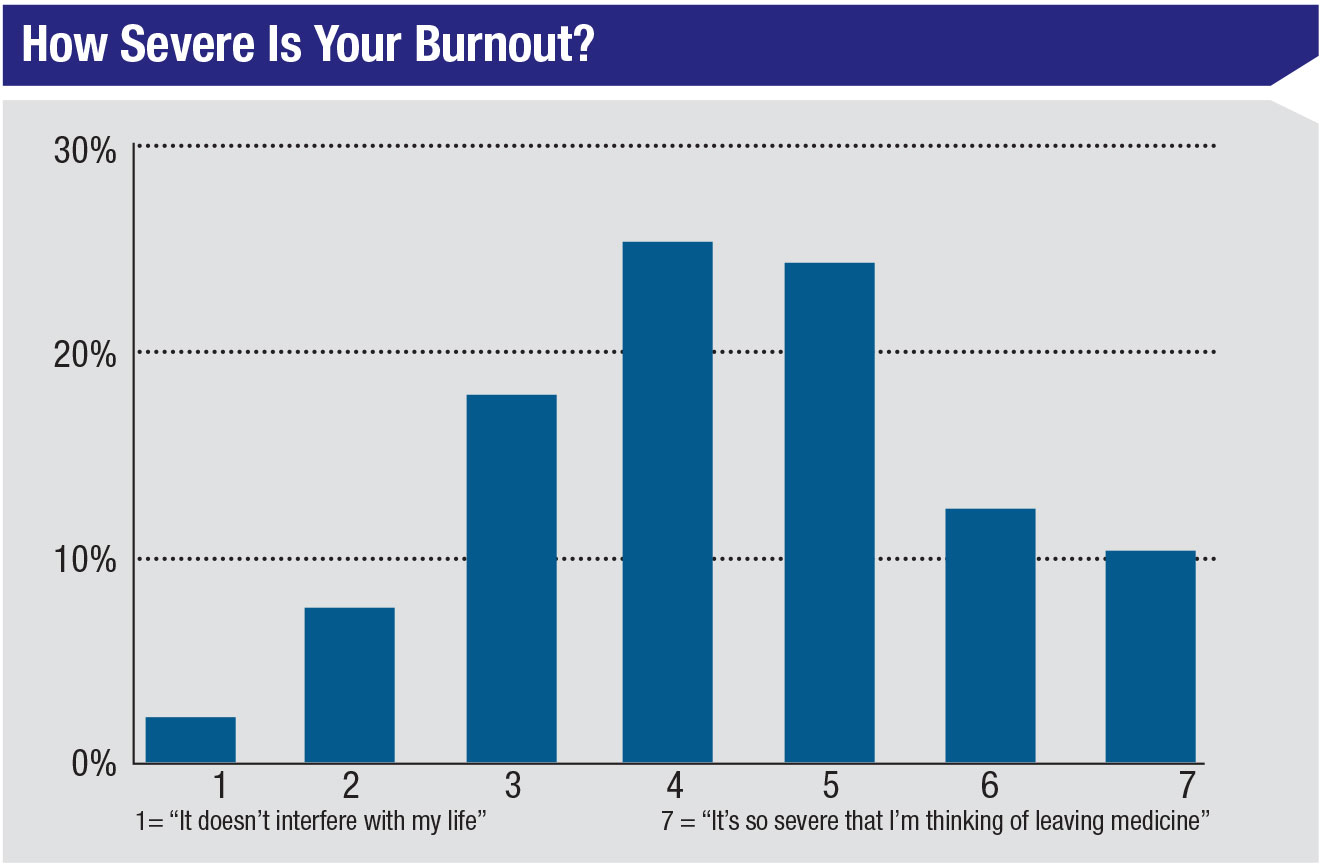

Dr. Connolly says the next question they asked was how their survey results compared to the rest of the nation. “Medscape has surveyed more than 15,000 physicians across the country in the past several years,” she says. “Their data is very similar to ours. For example, the specialties with the highest levels of burnout are the primary care specialties, such as internal medicine and family medicine. Ophthalmologists are about the third lowest among all physicians in terms of burnout, but we still have more than 30-percent burnout. This is no small problem.”

Delving Deeper

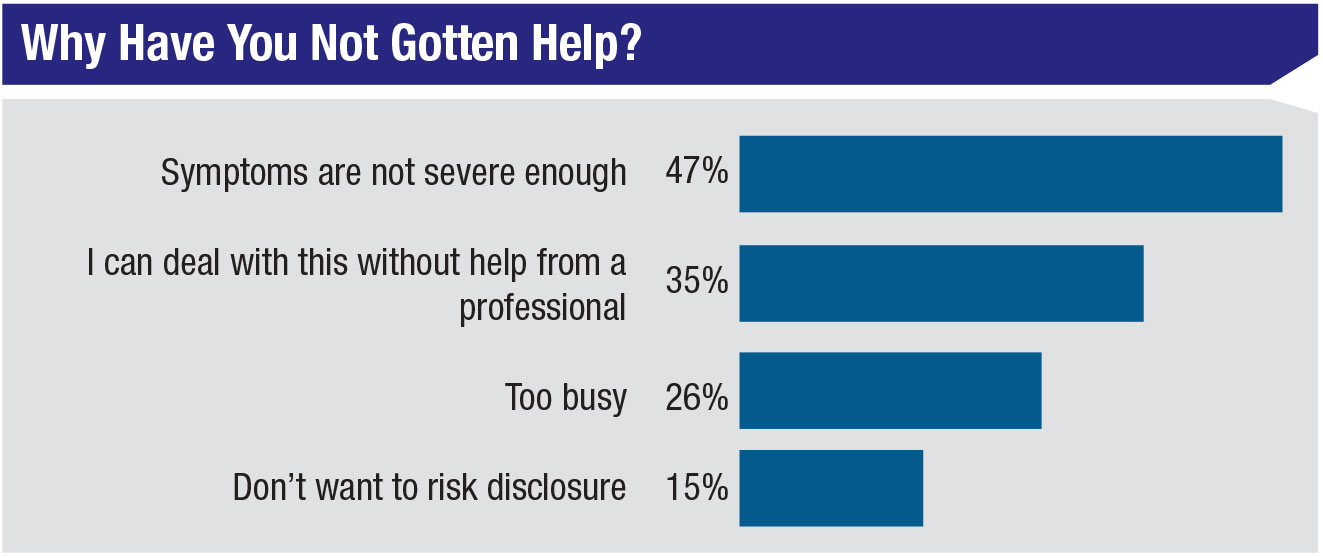

Robert Pearl, MD, the former CEO of The Permanente Medical Group, who now writes and lectures about how to improve health care in America, agrees that the obvious systemic problems physicians face contribute to burnout. However, he believes there may be more to this than meets the eye. “If you survey physicians about the problem of burnout, they all point to practical day-to-day issues,” he says. (For example, see the chart above.) “Those factors are real, of course, but they don’t fully explain the problem of physician burnout. There’s a second aspect to this that doctors often fail to recognize. Why do some specialties have a lot more burnout than others? It’s not about money, because some specialties, like pediatrics, make very little money but have a relatively low rate of burnout. I believe the answer has to do with the issue of mission and purpose.

“There’s a clash between the rapidly changing world around us and a very slowly changing health-care culture,” he says. “Physicians pursue medicine partly to make a good living, but also for mission and purpose. Right now, mission and purpose are being eroded. The culture of medicine and the world around us don’t connect the way they used to. As a result, medicine has become a far less fulfilling profession than it used to be. This change is easy to overlook, because we don’t usually notice the culture we’re enmeshed in. We just accept it. It’s only when it starts to clash with what’s happening around us that we start to notice it.”

Dr. Pearl says a key to dealing with this culture clash is to stop resisting change; instead, find ways to make it work to your advantage. “For example, one development that could help reduce cost and improve patient care is using artificial intelligence to evaluate the retina,” he says. “This could be far more efficient than the system we have today. Are ophthalmologists going to help that change occur, or resist it? My prediction is they’ll resist it, simply because it’s so different from their historical culture, and there are economic consequences. This is the clash between the old culture and the new science.

“Doctors need to lead the process of change, not be a brake on it,” he says. “We have to be the ones coming up with solutions, because we’ll come up with better answers than administrators or elected officials. The insurance companies and drug companies aren’t going to get this right. Physicians have to lead the way. If we don’t, the problem of burnout will just continue to grow.”

|

Realizing That You’re in Trouble

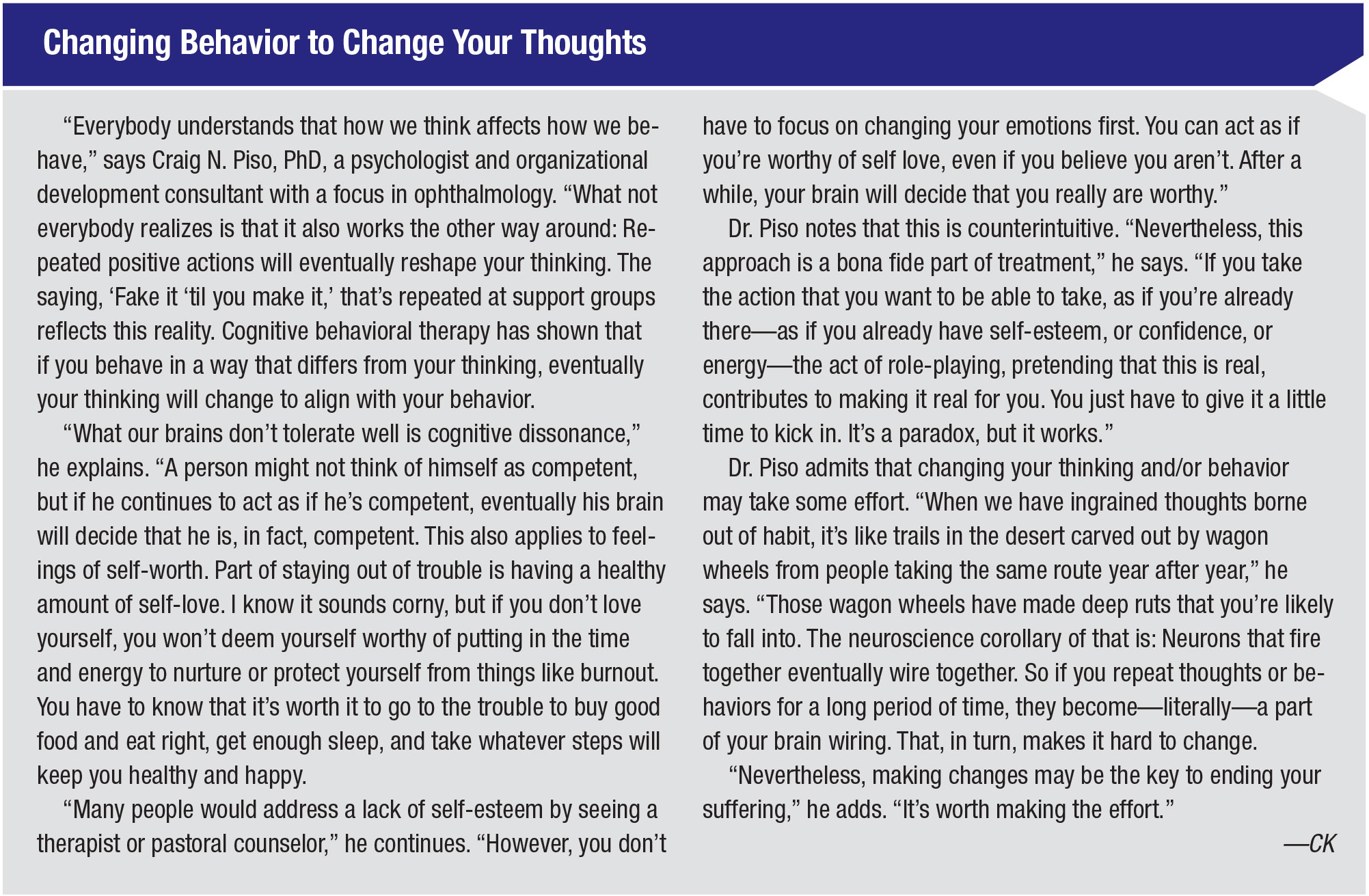

One reason the epidemic is growing is that physicians aren’t always good at recognizing when they’ve gone beyond just being tired to being in danger. Craig N. Piso, PhD, a psychologist and organizational development consultant with a focus in ophthalmology, offers some perspective on how burnout affects an individual.

“I like to think of human beings as having a reservoir of mental energy,” says Dr. Piso. “This is a concept I first encountered in the work of C. Nathan DeWall, PhD, a professor of psychology at the University of Kentucky. We need a full reservoir of psychological, emotional and cognitive energy to do all the things we normally do. When our reservoir of energy gets low, we start to get into trouble, not the least of which is—as Dr. DeWall describes it—a gradual erosion of our ability to control ourselves, physically, mentally and emotionally. That’s a key symptom of burnout.

“I like to take it to the next level,” Dr. Piso continues. “During burnout we start to lose what’s called ‘emotional intelligence,’ a concept championed by Dan Goleman in his book of the same name. Emotional intelligence refers to our ability to recognize and manage our emotions, as well as recognizing emotions in others and being able to influence them.

“Empathy is a big part of this—being able to put yourself in another person’s place and understand that person’s perspective,” he explains. “This is a cornerstone of building and maintaining great relationships, and lack of it is a sure sign of burnout. We become self-absorbed, distancing ourselves from others and cutting off relationships—including those close to us. We become more cold, uncaring and disconnected, and others notice it.

“A second aspect of this is what might be called emotional self-regulation—the ability to manage our own emotions,” he says. “When we’re healthy, emotions don’t overwhelm us. We can maintain an even keel, emotionally speaking. When we get burned out we start to lose control, and our emotions can get the best of us. We become more impulsive, irritable and agitated, and we lose patience more quickly.”

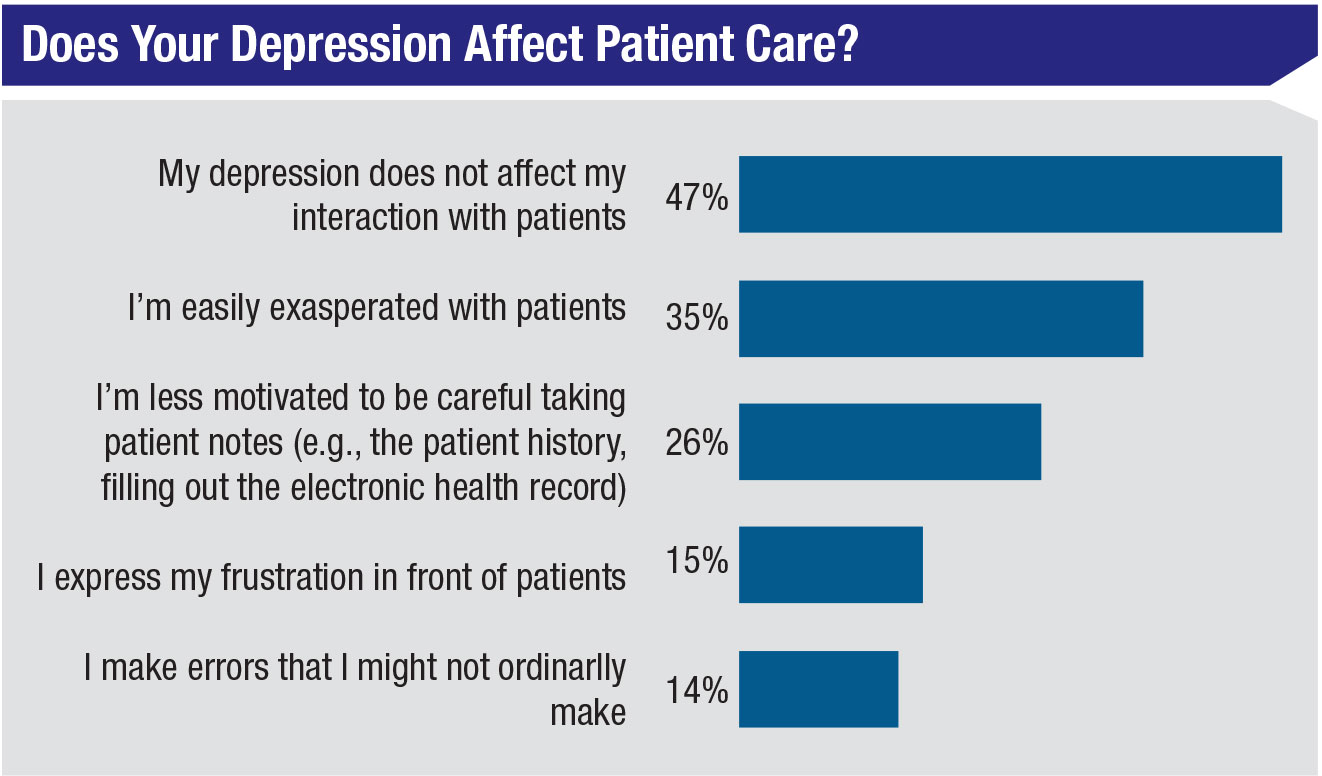

Dr. Piso notes that the signs and symptoms of burnout can be similar to those of clinical depression. “For example, people getting burned out start to feel exhausted,” he says. “They don’t have physical or emotional energy. They stop taking pleasure in things they previously might have enjoyed. They lose interest in what they’re doing. They start asking themselves: Why bother? Who cares? What’s the use?”

Dr. Pearl points out that recognizing burnout in yourself isn’t rocket science; he believes the danger lies in not realizing when it’s become a threat. “Most doctors who are burned out are well aware of it,” he says. “If you’re unhappy and depressed, you know it. If your work is less and less fulfilling, you know it. If you’re having increasing difficulty integrating your personal and professional lives, you know it. That’s why doctors report being burned out in those surveys. They clearly know what they’re experiencing.

“On the other hand, it can be a lot harder to realize that you’ve reached a point at which you’re in serious trouble because of the burnout,” he says. “Burnout can have negative consequences, all the way to suicide. Four hundred doctors a year commit suicide—more than one a day. So the problem isn’t so much knowing that you’re experiencing burnout; it’s knowing that you’ve reached a point at which you need to get help before things get out of hand.”

|

Addressing the Problem

Dr. Connolly says that to help come up with effective ways to combat burnout, her wellbeing committee has borrowed a model of professional fulfillment created at Stanford University. “The Stanford model lays out three things that are required in order to have professional fulfillment—or in this case, to prevent physician burnout,” she explains. “The three components are: a culture of wellness; personal resilience; and efficiency of practice. You need all three in order to prevent physician burnout. We’re working on improving them at our organization, and we’ve had good results so far.

“The first component is a culture of wellness,” she says. “Basically, physician wellness has to be a priority in your practice. You can’t make changes for the better if the problem of burnout isn’t taken seriously. Fortunately, our CEO—who is an MD—has made it a goal to bring joy back to the workplace. He created the Joy of Work Ini-

tiative, and it’s part of our budget. That means we have funding to work on alleviating physician burnout.

“The second thing is personal resilience,” she continues. “Through the wellbeing committee we’ve implemented a number of programs to help physicians with this. For one thing, our research showed that physicians who attended more physician meetings had lower levels of burnout, so we realized that socializing with colleagues might be helpful. With that in mind we’ve sponsored a number of social events, involving things such as eating together, visits to art museums and attending concerts. We also have a wellbeing retreat weekend every year-and-a-half for physicians and their families. These events have been popular and well-attended.

|

“Putting money towards social events might sound frivolous, but it turns out that we can’t afford to not do it,” she notes. “Keeping people from feeling isolated is very important. Paying for a happy hour, for example, isn’t that expensive. On the other hand, it’s been shown that it can cost a medical organization as much as $500,000 per year to lose a physician. Holding social events increases the sense of community in a practice and increases the happiness set point. The return on investment is high.

“Another way to increase personal resilience is through mindfulness training,” Dr. Connolly continues. “The original Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction course was designed by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical School more than 40 years ago; the techniques taught in the course have been shown to reduce depression, stress and anxiety. His course is now offered all over the country. In fact, our organization has been offering it to patients and the community for about 20 years.

“Five or six years ago I took the course myself, and it was great,” she says. “However, I realized it would have been even more worthwhile for me if the other people in the class were also physicians experiencing things similar to what I was going through. So I suggested to the wellbeing committee that we offer a modified version of the course to our physicians, free of charge. We got approval and funding and then worked with the mindfulness teachers we already employed to create a modified version of the course designed specifically for our physicians. We’ve been offering it for the past two years, and it’s been very popular. It really does help our doctors avoid burnout.”

Dr. Connolly notes that the third aspect of the professional fulfillment triad—efficiency of practice—is probably the hardest to accomplish. “It’s hard to make the system more efficient,” she admits. “Many changes that can increase efficiency require an investment of time and money. However, in our organization, a few simple things have been helpful. For example, we’ve found that having the same support staff every day, a consistent ‘health-care team,’ improves efficiency and wellbeing for providers and patients alike.” (For more suggestions, see the pearls below.)

|

Keeping Burnout at Bay

As noted earlier, a little burnout may be hard to avoid for many physicians. The key is making sure you address the problem head-on and do everything possible to reignite joy in your work and prevent further decline. The following strategies can help keep burnout from getting out of hand.

• Watch out for all-or-nothing negativity. Dr. Piso says this is a sign of a more serious level of burnout. “At this stage people start seeing everything as awful,” he explains. “A healthy person can tease out the good and separate it from the not-so-good, but a person with advanced burnout just lumps it all together: ‘Life sucks and then you die.’ ‘I can’t succeed at anything and I never will.’

“That type of depressive thinking should be a huge red flag that you’re in trouble,” he notes. “The worst part about this type of thinking is that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy and contributes to a more intensive downward spiral. It can culminate in serious depression—or worse.”

• Don’t take on the role of victim. Dr. Piso says this is one of the most important parts of preventing or recovering from burnout. “It’s crucial to take personal responsibility for being the steward of your own heath and wellbeing,” he says. “The biggest mistake people make is externalizing, blaming, making excuses and feeling like a victim. You have to stop buying into the idea that the circumstances stressing you out are somebody else’s fault. If you take on the role of victim, you’re abdicating the power to improve things. The mindset that will put you back in control is: I’m responsible; I’m the steward. The buck stops here. It’s up to me to make things better.”

• If you find you’re turning inward, do the opposite. “When we get stressed out, we turn inward,” Dr. Piso notes. “We make it all about ourselves. We don’t necessarily do it consciously, and it’s usually not malicious. It’s just dysfunctional. It’s like a form of self-preservation when we’re feeling attacked, in danger and depleted.

“The solution is to do the opposite,” he says. “When you’re getting tired and thinking ‘What’s the use? Why bother?’ do the opposite of what you’re tempted to do: Turn outward. Become altruistic. Decide to get even more focused on taking great care of your patients and your staff, even if you don’t feel like you have it in you. Because something miraculous happens when you put your heart back into your work—what I call ‘working wholeheartedly.’ We know from neuroscience that being of service to others, unselfishly and unconditionally activates a part of the brain that makes us feel joy, fulfillment and satisfaction, and increases our energy.”

Dr. Piso acknowledges that doing this may seem like a huge leap when you’re already feeling burned out. “You have to prime that pump,” he says. “You prime it by saying, I’m going back to the reason I went to medical school in the first place. Most likely, before you thought about money, you thought it would be really cool to heal people, ease their suffering, or perhaps do surgery and correct problems. Go back to focusing on that! Work wholeheartedly.

“It’s not necessarily logical, but after 40 years as a psychologist working with thousands of people, I can tell you that this secret sauce is real,” he adds. “Focus on the idea of helping others rather than the obstacles you face, and you can come back from burnout. This is something you can do every day. You don’t have to wait for a trip to Italy.”

• Remember that difficult life circumstances can increase the risk of depression and burnout. Dr. Connolly says that one of the things her group does to combat burnout is take note when a physician is at higher risk because of challenging life circumstances, such as dealing with a death in the family, having a serious illness or going through a divorce. “Doctors in these situations are at risk of falling way below the curve,” she points out.

“We’ve set up a system to address this type of circumstance discreetly,” she continues. “When someone on our wellbeing committee realizes that a doctor is under unusual stress, we reach out and let the doctor know that we’re here if he or she needs someone to lean on. We’ve received additional training in this area, and we’re available to provide emotional support. We can also direct the individual to additional resources when necessary.

“It might be even easier to manage this in a small practice where everyone knows everyone else,” she says. “One person could be assigned to stay alert for doctors or staff dealing with tough life circumstances, or a committee of two or three people could get together once a month to talk about issues like this.”

In the Office

Here are a few steps you can take to improve things and lower stress in your workplace:

• Set up your exam rooms to make your job as easy as possible. Dr. Connolly describes two changes her organization made to exam rooms that have helped to eliminate a little bit of stress. “First, we make sure every exam room is set up exactly the same,” she says. “That allows us to standardize where everything is kept, so we’re not wasting our time looking for things.

“Second, we aim to have a printer in every exam room so there’s no disruption if we want to give a handout to the patient or print out a prescription,” she continues. “If we have to leave the room to go to the printer, we’ve already broken eye contact with the patient. If there’s a printer in every exam room, we can continue to have eye contact with the patient and we don’t disrupt the flow. This is helpful, and it doesn’t cost much.”

• Look for additional ways to offload tasks. “As part of our effort to make things more efficient, we’ve tried to figure out which tasks don’t really need to be done by an MD,” Dr. Connolly says. “For example, we physicians receive numerous emails from patients every day, and patients expect an immediate response. We’re now aiming to have our support staff weed through the emails and handle whatever they can on their own, such as helping a patient schedule an appointment, or forwarding medical records or DMV forms. It’s worth stepping back for a minute and considering if there are tasks you’re doing that could be done just as well by another staff member.”

• Remember that your team takes their cue from you, creating a feedback loop. “In American culture, people see doctors as powerful individuals,” notes Dr. Piso. “They’ll follow your lead, so your mood and attitude sets the tone for your team. What most people forget is the counterintuitive part: The mood of your team then affects you in return.

“So, if you want your team to be more energized, have more fun, work harder and be more productive, you need to model that behavior,” he says, “even if you have to ‘fake it until you make it.’ If you do this—even when you’re not feeling 100 percent—the people around you will follow your lead, and you’ll find yourself surrounded by positive people. That, in turn, will make it easier for you to avoid becoming tired and negative.”

• Even if you feel down, don’t complain to your team or patients. “Complaining will always backfire, because people almost always see a doctor’s life situation as more privileged than theirs,” notes Dr. Piso. “They won’t understand that you’re dealing with burnout. They’ll say, ‘What gives this doctor the right to complain? This is a successful, powerful person who owns three Porches and four houses and has more money than God.’ You’ll never get sympathy, and it will lower people’s estimation of your character. So save your complaints for people who understand that you’re struggling with burnout—especially those who may be in a position to help you deal with the problem.”

• Keep your focus on improving patient care. “Many of the problems that lead to burnout are tied to the problems patients are having getting help in the current system,” notes Dr. Pearl. “We need to be proactively looking for ways to provide more high-quality care at a lower cost. If we succeed, we’ll end up addressing many of the factors that have helped create burnout in the medical profession.”

Make the Most of Resources

There are plenty of things you can do to mitigate the challenges of being a physician today:

• Take the time to do things that add purpose to your life. “Many ophthalmologists travel to other countries and do intraocular lens replacements for patients with cataracts,” notes Dr. Pearl. “They come back energized.

“Of course,” he adds, “many physicians will say, ‘I have no time for that.’ If you’re experiencing burnout, taking the time to do something like this will not only help save the sight of the people you reach, it might save your life.”

• Reinstate socializing with your peers. Dr. Pearl notes that in large medical systems physicians sometimes have a physician dining room where doctors of many specialties and backgrounds interact during meals. “Meeting with your peers does two things,” he says. “First, it minimizes a sense of isolation. You can see that your peers are dealing with challenges similar to yours and find out how they’re dealing with them. Second, it makes it possible for our medical culture to evolve. That evolution is necessary for our culture to keep up with the rapidly changing world around us.”

Dr. Pearl acknowledges that there’s plenty of interaction taking place via social media, but says that’s not sufficient. “There’s a huge amount of discourse taking place online,” he notes. “However, it’s mostly people with the same beliefs talking to each other about their unhappiness with the current situation. They’re not asking what we can do differently, so it’s not helping medicine to evolve.”

• Give those close to you permission to let you know how you’re doing. “There are many things you can ask family, friends and coworkers to do to help you deal with burnout, but one of the most helpful is to ask a few people close to you to be your accountability partner,” says Dr. Piso. “Of course, you have to select the individuals judiciously. But let them be your social mirror and tell you if your behavior is headed in a bad direction.

“Think of someone who tells you you have parsley in your teeth at a cocktail party,” he continues. “You may feel a little embarrassed, but you’re grateful that they told you, because they could see what you couldn’t see. So, ask people you feel close to to do that for you. When you’re starting to be irritable or selfish, insensitive, short-tempered, impatient, lackluster, they’ll bring it to your attention so you can take action.”

Dr. Piso points out that those close to you are more likely to do this if you give them full consent. “You have to expressly give them permission to upset you,” he says. “Ask them not to do it in public, or in a malicious way, but tell them you want to know if you’re starting to exhibit signs of burnout. This is far better than having them be silently worried or annoyed while you get deeper in trouble.”

• Check out Yale University’s “happiness class.” “A very interesting set of conversations is being held right now by Laurie Santos, PhD, a professor from Yale,” says Dr. Pearl. “Her 20-hour class, ‘The Science of Wellbeing,’ delves into what does and doesn’t actually make people happy. It’s become the most popular course in the history of Yale University. One out of every four students takes it. Best of all, anyone outside of Yale can now take it, for free: It’s available online at no cost.

“Dr. Santos shows how and why the things we expect to bring us happiness—and I would add the word ‘fulfillment’—often fail to do so,” he continues. “For example, many people believe that having more money will make them happier. The data says that’s not true, once you’ve reached a certain basic level of income. (That income level, by the way, is well below the average ophthalmologist’s salary.)She also spells out many specific things you can do that will help to make you happier.

“Taking her course is a good investment of your time, even if you’re not burned out,” he concludes. (For more information, visit coursera.org/learn/the-science-of-well-being#)

• Learn some of the “mindfulness” techniques. “I realize that a small practice may not be in a position to duplicate some of the things we’ve done, such as creating a special version of the popular mindfulness course, tailored to physicians,” says Dr. Connolly. “However, there are many other things anyone can do for free or very little cost. There’s plenty of free information about mindfulness and the course online. Also, some of the techniques it teaches are very simple, such as learning to do mindful breathing. You don’t have to attend a formal program to pick up some of those techniques.”

Dr. Connolly offers another example. “It may sound overly simple, but one thing I’ve learned to do is keep a small, smooth stone in my pocket,” she says. “When I find myself feeling stressed, I put my hand in my pocket and feel the smoothness. It reminds me to breathe in and out and pay attention to my breath. I may take one minute to just meditate, even in the hallway between patients. It’s amazing how much difference small things like this can make.”

• Take advantage of free online meditation apps. “The practice of ‘sitting meditation’—even if you only do three minutes a day, ideally in the morning—sets the tone for the day,” says Dr. Piso. “It’s like calibrating your mind and body and emotions to be in a more helpful mindset. There’s a lot of free material online to help guide you through doing this, and it can make a big difference.

“I know some doctors will say, ‘I don’t have three minutes in the morning.’ Well, think about it,” he says. “If you don’t have three minutes a day to invest in yourself by doing something simple and easy that might really help you, that’s an early warning sign that you’re already a long way down the wrong road. That’s diagnostic. You’re living in denial and putting yourself at greater risk.”

Don’t Wait to Ask for Help

The greatest danger when experiencing burnout is that you’ll simply treat it as an unhappy fact of life and do nothing about it. Everyone with expertise in this area agrees: If you’re experiencing burnout, don’t wait to take corrective action.

“If you’re hiking and you’re not sure you read the path signs correctly, it’s better to stop and retrace your steps when you’re only 50 yards down the wrong path than to wait until you’ve gone five miles,” says Dr. Piso. “Similarly, it’s easier to do something to counteract your burnout when you’re just starting to get exhausted and noticing your negativity and lack of empathy and lack of emotional self-regulation. If you choose to ignore it or pretend it will go away on its own, you’ll find yourself getting deeper and deeper into burnout—and potentially in the throes of depression. As in any type of health care, early detection and treatment is the best medicine.”

Dr. Pearl notes that seeking help for psychological stress is sometimes seen as a personal failing. “We use the term ‘mental health’ as a pejorative in this country, as if being overwhelmed by stress is a failure of the individual,” he says. “Burnout is not a personal failing. If you’re in this situation, it’s not your fault. You shouldn’t blame yourself—but you SHOULD take action. The symptoms can be debilitating, and they can lead to suicide. So don’t blame yourself for needing help dealing with this. Instead, take action.”

Back in the Driver’s Seat

All of this can be boiled down to 10 key points:

1. Take the problem of burnout seriously. Make dealing with this a priority in your practice and in your life.

2. If you recognize that you’re showing signs of burnout, don’t wait for a crisis before addressing the problem.

3. Be aware that unusually difficult periods in your life put you at greater risk; ask for help dealing with your situation.

4. Do more socializing with your peers. Don’t become isolated.

5. Take advantage of the resources around you. Investigate the concepts in the “mindfulness” curriculum; if possible, take a course. In addition, take the online version of Yale University’s “happiness class.”

6. Find ways to offload day-to-day burdens in the office that you might have previously overlooked.

7. Instead of resisting changes in the profession that you dislike, look for ways to turn them to your advantage.

8. Don’t take on the role of victim; doing so takes away your ability to change things for the better. Focus on what you can change, not the things beyond your control.

9. Take the time to do things you love. Do things that remind you why you went into medicine—even if it means a loss of some income.

10. Give people you trust permission to provide feedback on how you’re doing.

“Again, it’s important for doctors to understand: If you’re suffering from burnout, you need to get help,” says Dr. Pearl. “You didn’t do anything wrong. You need to make changes that will bring you happiness and fulfillment, not because the problem is your fault, but because this is your life.”

Dr. Connolly says that perhaps the most important way to avoid burnout is to take a moment each day and remember why you became a doctor—and why you chose ophthalmology in particular. “Even with all of the hassles and the ways in which medicine has changed, it’s still one of the best professions,” she points out. “It’s truly an amazing thing to be doing. Every single day, we physicians have the unique opportunity to make eye contact with other another human being. We have the opportunity to interact with people in a deep and meaningful way and make a difference in their lives. That truly is a great privilege.

“At the end of the day, if we can simply remember that, it will make the whole thing worthwhile,” she concludes. “The rest of it is just paraphernalia. If we can shift our focus back to all the positive things that are still here, we’ll not only be able to withstand the negative things, we’ll extinguish burnout and reignite our joy in medicine.” REVIEW

Dr. Piso is the author of the book “Healthy Power.” Dr. Pearl is the author of the bestseller “Mistreated: Why We Think We’re Getting Good Health Care and We’re Usually Wrong.” All profits from the sale of Dr. Pearl’s book go to Doctors Without Borders.