With a large financial investment at stake, Genentech has done its best to keep the ophthalmologic community apprised of the Lucentis clinical trial results. But many surgeons have little experience with Avastin, and even fewer have treated patients with both. To find out more about Avastin, how it compares to Lucentis, and how the FDA approval of Lucentis may affect both drugs' use, we spoke to a number of surgeons who have extensive experience with one or both of them.

The Avastin Phenomenon

Ron Gallemore, MD, PhD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the Jules Stein Eye Institute, UCLA School of Medicine, is a partner at Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group in Los Angeles, a major clinical trial center for the SAILOR (Safety Assessment of Intravitreal Lucentis for AMD) study. Dr. Gallemore notes that in the recent past, when Lucentis was available only to those involved in clinical trials, many ophthalmologists were open to trying something similar. "Phil Rosenfeld got the bright idea to try Avastin," he says. "Avastin is a full-size antibody to VEGF, the factor that causes leakage in wet macular degeneration. Lucentis is actually an antibody fragment that's been engineered to have a higher affinity for VEGF, and hopefully better penetration in the retina because of its smaller size."

Fareed Ali, MD, FRCSC, director of clinical research at the Canadian Center for Advanced Eye Therapeutics, says that, considering the medical-legal situation in the United States, he's surprised how quickly Avastin was accepted. "Avastin is a cancer drug, and this use is off-label," he notes. "There's a theoretical risk of endophthalmitis and blindness."

Nevertheless, the positive results of Avastin treatment quickly became clear. "We did the first injections of Avastin in Canada here in our center," Dr. Ali says. "We were shocked and surprised by how quickly patients accepted it, given that it's an off-label treatment. And we were astonished and delighted by the excellent clinical results. My partner and I were one-upping each other: 'I have a patient who went from 20/200 to 20/50.' 'I have a patient who went from 20/200 to 20/30 in two days.' Who'd have thought we'd ever be talking like that about AMD patients?"

"People started using it, and word got around," he continues. "Many physicians assumed that, despite the good reports, only one out of 100 patients would accept it. It turned out to be the opposite: Everybody wants it."

Dr. Gallemore concurs. "With Avastin we've had a remarkably high rate of successful treatment—stabilization and improvement of vision in the majority of patients," he says. "It's now become a major player in the treatment of all forms of macular disorders associated with leakage, such as wet macular degeneration, branch retinal vein occlusion, central vein occlusion and diabetic macular edema."

Some of the most interesting work with Avastin is being carried out by researchers at Schepens Retina Associates in Boston as part of their benefactor-funded Avastin project. The project hopes to find ways to detect neovascularization earlier, so treatment can be started as early as possible. Their researchers also hope to characterize the response to Avastin as carefully as possible to determine the true significance of changes that follow use of the drug.

We spoke with Peter Hovland, MD, PhD, who runs the project. "When we first started using Avastin back in September, 2005, it was sort of on the fringe," he says. "Many doctors were violently opposed to even trying it. Since then, we've probably injected fewer than 50 patients, but everyone has had at least two injections. The response has been impressive—we've always been able to measure either an improvement in visual acuity or improvement on OCT. Some patients—perhaps 10 percent—have seemingly been 'cured' by treatment with Avastin, meaning that their active leakage has stopped. In some patients vision has returned completely to normal. A clear majority of those treated feel like they've gotten some beneficial effect, and every patient I've treated has asked to be reinjected."

Dr. Hovland notes, however, that response time varies, depending on the problem you're treating and its severity. "If someone has an acute hemorrhage in his eye and his retina is slightly swollen, he may get a response within a day after the injection," he says. "On the other hand, if he has diabetic macular edema, it may be months before you measure any appreciable improvement in visual acuity. Those conditions tend to be longer-standing before they're treated, and I think recovery should be expected to take longer as well.

"Avastin has now been widely adopted and is arguably part of the standard of care," he concludes. "There's no question that it works, and it appears to be affordable therapy."

The Follow-up Dilemma

One of the important issues that remains unresolved is how often and how long either drug needs to be continued in any given patient in order to avoid a relapse into leakage. Although a study is under way to provide some information about this in regard to Lucentis, it's clear that most surgeons are proceeding with caution.

"Unlike the paradigm that was proposed for Macugen therapy—treatment every six weeks—here, each patient requires independent evaluation at every office visit," explains Dr. Hovland. He says that he's simply monitoring those patients whose active leakage appears to have been stopped by Avastin. "We're hoping that the disease will not recur, but we don't know when, or if, the drug will wear off. However, I've had patients in whom the effect has clearly worn off after about three months. These patients we reinject.

"The question is, how long are we going to be doing this?" he continues. "Right now I'm comfortable following these patients every two to three months. But it's not clear what the optimal scheduling for follow-up visits will be."

Mark W. Johnson, MD, director of the vitreoretinal fellowship at the National Retina Institute in Chevy Chase, Md., has been an investigator in all of the Macugen and Lucentis trials. "At this point reinjection is somewhat individualized, based on exam results," he says. "With Avastin, it seems the disease begins to recur in the three to six month range. Maybe we can head that off by giving the patient a dose every three months. But we don't have good predictors. We need to be studying the clinical factors closely—the OCTs, the angiograms—looking for clues that might be predictive."

Dr. Ali notes that the patient's practical concerns can be a big part of the equation. "Some of these patients live far away, so the cost and inconvenience of coming in so often can be a burden," he says. "They're trusting us to do what's in their best interest—and not just from a clinical point of view. I may say, 'The best thing for you is to continue monthly.' They may say, 'How much of a risk am I taking if I don't do that?'

"Our Avastin protocol, so far, is a treatment every six weeks for three or four initial injections," he adds. "After that we watch to see what happens. But it's still a challenge to know how often to inject it. It may turn out to vary from patient to patient."

|

|

Why Patients React Differently

Regardless of which drug is used, it's clear that some patients get remarkable results while others don't. Since understanding the reasons for this could have a profound effect on treatment success and the direction of further study, we asked our surgeons what they thought might explain it.

Dr. Gallemore notes that part of the explanation may simply be how far the disease has progressed by the time you treat the patient. He says that in his practice, patients who respond to a single injection tend to be the ones who have a healthier-looking retina, a small amount of leakage, and are younger in age. "Patients with the kind of large lesions found in advanced dry macular degeneration tend to be more difficult to treat, and this happens more often in older patients," he notes. "I think a thicker retina may release more of the VEGF molecules because the pathways involved in VEGF release are tied to the amount of damage happening to the retina."

Dr. Johnson says different outcomes may reflect variations of the disease itself. "I suspect there's a differential response rate based on the type of blood vessels you're dealing with," he says. "For example, we're doing a small pilot study using Lucentis to treat retinal angiomatous proliferation, a variation on AMD that usually involves intraretinal rather than subretinal hemorrhages. So far, 100 percent of the patients in this category are improving. But this is a specific, atypical subtype of AMD that may be more VEGF-driven."

|

Dr. Johnson also notes that treatment differences could be explained by multiple causative factors behind the disease. "Our current focus has been largely on VEGF and its role in AMD," he points out. "But there are a lot of other factors that we haven't begun to target. For example, what role do other vascular growth factors like matrix metalloproteinase play?

"One thing I've seen as an investigator in the Macugen and Lucentis trials is that some patients who are three and four years out are having progressive decline in vision without showing any reactivation of their neovascularization," he continues. "This suggests that there may be other components of macular degeneration that we're not addressing at all. For example, there may be a neurodegenerative component to AMD. We've all seen patients with occult neovascularization who don't have visual symptoms and haven't lost vision from it, and there are pathology and autopsy studies that suggest that some patients have long-term neovascularization without ever developing symptoms. So there may be a subset of AMD patients in whom neovascularization is actually a compensation for something else.

"If we can identify some of the clinical features and understand some of these subtypes better," he concludes, "we might get a better sense of who's going to respond better to which drug. We need to understand the disease in its entirety."

Avastin or Lucentis?

With Lucentis now approved, ophthalmologists have to decide which agent to offer to their patients. But with no clinical data making a direct comparison between Lucentis and Avastin, the deciding factors could have little to do with health benefits.

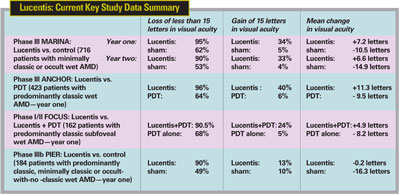

"A lot of my patients have had marked improvement in vision and reduction in edema with just a single injection of Avastin," says Dr. Gallemore. "Many have also had home runs with Lucentis. But Avastin has not been studied in a randomized, controlled clinical trial, and we're very impressed by the Lucentis data. So personally, I will be using Lucentis as my primary treatment of choice."

Dr. Hovland, whose research currently focuses on Avastin, says he believes the treatment effects of the two drugs are probably similar. "There's been some speculation that Avastin might even be better than Lucentis," he says. "But Lucentis certainly has very impressive clinical trial data. We would consider trying it and comparing it to Avastin."

The fact that Lucentis now has FDA approval is likely to be key for many ophthalmologists. "If a drug has FDA approval for injection into the eye, we tend to assume it must have undergone some sort of risk evaluation and be safe to use," says Dr. Hovland. "The flip side of that is a perceived risk to the doctor when using a drug that isn't FDA-approved. Many physicians think, 'This is unproven, it's unsafe, it's not covered by insurance, I'm afraid my patient might sue me.' It's easier for a treating physician to prescribe a drug that has FDA approval. Macugen has clearly benefited from that.

"With FDA approval, Lucentis will enjoy the same advantage," he continues. "Even if it's expensive, Medicare pays for it or it comes out of the patient's pocket, and it means less risk to the physician. Avastin isn't likely to get FDA approval because, ironically, Genentech owns both Avastin and Lucentis. They have no financial incentive to get Avastin approved."

On the other hand, Dr. Hovland notes that many off-label treatments have been widely adopted by ophthalmologists. "In my opinion, it's a fallacy to argue that simply because something has FDA approval, you should choose it. You really have to stick with the bottom line: What's best for the patient? If you're proceeding in a thoughtful, rational manner, in concert with your colleagues, you should be able to treat your patient with confidence with the best therapy. That might turn out to be Avastin."

Dr. Gallemore agrees that lack of FDA approval isn't sufficient to warrant eliminating Avastin. "Although we don't have clinical data on Avastin, we do have uncontrolled data that is very impressive, and that legitimizes its use," he says. "We rarely saw marked improvement in vision with other treatments, and now we're seeing an abundance of great results with Avastin. That gives power to the limited statistical data.

"At the same time," he continues, "there are potential side effects associated with administration of anti-VEGF drugs. The side effects have been studied carefully for Macugen and Lucentis, but not formally for intraocular use of Avastin, so your liability is somewhat higher with Avastin. But it's reasonable to consider it, and I don't think it should be eliminated from the choices for patient care.

"However," he adds, "if you're offering Avastin to your patients, it's critical to have carefully formulated informed consent to minimize your liability."

|

Either Way, We Win

With Avastin's use becoming widespread and Lucentis receiving FDA approval, one thing seems certain: It's a whole new era for AMD treatment, and the changes may just be beginning. Dr. Gallemore sees better delivery systems as the next wave of change. "I think a vehicle that allows sustained delivery of anti-VEGF therapy, either in the form of an implant or an integrated gene product in the eye, will be the great advance of the future," he says. "And I don't think this technology is far off."

"In the future, we won't be frustrated by a lack of treatments," adds Dr. Ali. "I think every year some big new development will be announced. The challenge for us now is not treating the disease, but managing the delivery of the treatment to the patient."

1. Ferris FL, Davis MD, et al; Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) Research Group. A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:11:1570-4.