Currently, surgeons are beginning to gather results from studies of Epi-LASIK, a procedure invented by Greek surgeon Ioannis Pallikaris. These initial results appear to show that the procedure, which is a fusion of LASIK and LASEK, may be able to yield acceptable results in low myopes without the risk of ectasia from cutting a relatively thick LASIK flap, or the risk of epithelial cell death from LASEK's use of alcohol. Here is what these surgeons are finding, and how the procedure compares to other refractive surgeries.

The Procedure

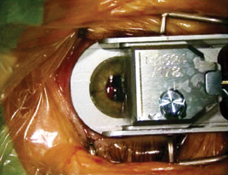

The Epi-LASIK procedure uses a special device resembling a microkeratome, developed in part by Dr. Pallikaris. It uses an oscillating blunt plastic blade rather than a sharp metal one to incise the epithelium just below the basement membrane. The epithelial separator creates a thin, hinged epithelial sheet similar to that made in LASEK but without the use of potentially toxic alcohol. Currently, two companies make such epithelial separators: Norwood Abbey (Melbourne, Australia), which acquired the rights to CIBA Vision's Centurion SES EpiEdge Epikeratome; and Gebauer Medizintechnik (Neuhausen, Germany), maker of the Epi-lasitome.

|

| The steeper a cornea is, the more trouble the epithelial separator's oscillating, blunt plastic blade has with making a flap. |

The Epi-LASIK procedure is proposed as an alternative for low myopes and patients with thin corneas (to avoid possible ectasia from a full LASIK flap). It's also a possible choice for patients who might be struck in the eye as a result of their occupations or hobbies, such as soldiers, firefighters, policemen or boxers; since there's no LASIK flap to be dislodged, these patients won't risk losing or displacing a flap.

Another possible benefit of Epi-LASIK is the ability to convert to a traditional PRK if there's difficulty with the flap.

"Even if there's a problem during flap creation," says Antwerp, Belgium's Erik Mertens, MD, who has done just over 50 Epi-LASIK cases, "you can still convert the surgery to a PRK and then use the partial flap to cover the stroma, but such problems haven't occurred often." This may not always be possible, however, if the flap cut includes some stroma, since this may introduce the potential for haze.

Dr. Mertens says the quality of the cut depends a lot on the cornea's dimensions. "It depends on the diameter and the steepness," he says. "The steeper it is, the more problems the [separator] has making a good epithelial flap, and the more power you need to make a flap. Above a K reading of 45 or 46, you have to be careful. If the cornea's too steep, I've had cases in which the oscillation of the plastic piece stopped, resulting in a partial flap. The incidence of this is less than 10 percent."

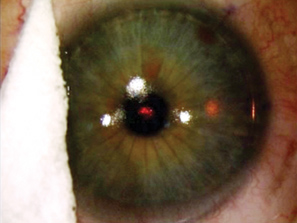

After the surgeon finishes the ablation, he replaces the epithelial flap and then places a high-Dk contact lens on the eye to keep the epithelial flap in place while it reepithelializes. The choice of lens is another key factor, say doctors.

"I think the contact lens is very important," says the director of refractive surgery at Germany's Mainz University, Burkhard Dick. "It should be a high-Dk value lens, offering good oxygen transmissibility. If it's not, the epithelial cell layer might die."

Dr. Mertens says that, in the beginning of his Epi-LASIK learning curve, he had a problem with the contact lenses the patients used postop. "But, when I switched to a contact lens with very high oxygen permeability, like the PureVision (Bausch & Lomb) or the Focus Night and Day (CIBA Vision), the eyes healed nicely," he explains.

In most cases, the eyes reepithelialize by the third day postop.

Epi-LASIK's Results

Based on preliminary results, it appears Epi-LASIK could possibly rank just below LASIK, but above LASEK and PRK, in terms of visual recovery and pain.

Dr. Dick is part of a multicenter trial of Epi-LASIK, and has six-month results on 22 cases performed with the Centurion separator and the Carl Zeiss Meditec Mel-80 excimer laser. The patients' preop errors ranged from -1.25 D to -5 D (mean: -3.25 D) with less than a diopter of cylinder.

After six months, the average refraction went from -3.25 D preop to

-0.1 D. There was no loss of lines of best-corrected acuity, and 19 percent of the patients gained a line or more of best-corrected vision.

|

| The surgeon protects the flap hinge during the ablation. |

"The speed of visual recovery was very fast," says Dr. Dick. "After three days, the mean acuity was 20/40 without correction, which compares favorably with the LASEK procedure, but is still inferior to LASIK."

He says that, though predictability is more or less a function of the laser, all eyes were within ± 1 D of intended refraction, and, by three months, 82 percent (18 eyes) were within ± 0.5 D. All the eyes see 20/30 or better at six months.

"Interestingly," he says. "We conducted histopathological tests on the eyes of patients who allowed us to convert the procedure to a PRK so we could study their epithelial flaps. We found the epithelium was fully intact after separation, which is definitely different from LASEK procedures using alcohol."

Dr. Mertens says that he thinks that the pain patients experience is less than standard PRK or LASEK, based on the results of a postop patient questionnaire. Dr. Dick also asked questions of patients. In his case, all the patients said they'd undergo the same procedure again. Some surgeons feel, however, that a comparison study in which one eye receives PRK and the other Epi-LASIK gives a true comparison of pain levels.

As for Dr. Mertens' visual results, "Days one and two are very good most of the time," he says. "Then, for days three and four, the acuity drops off a little bit. But, after that, it climbs back to being better than days one and two. I always tell Epi-LASIK patients that they should be able to drive after a week, which is a big difference from the one-day LASIK recovery period.

"The refractive results are comparable to PRK and LASIK, but the big difference is the relatively greater patient comfort compared to PRK and LASEK," he says. "I still prefer to use LASIK because the recovery is much faster than the other procedures, but I'll use Epi-LASIK for dry eyes, thinner corneas, patients who are scared of dislodging the LASIK flap, or those with potential for dislodging a flap at work."

Dr. Mertens says corneal haze hasn't been a problem, which may be a function of the relatively low corrections. "The maximum haze I've seen is 0.5+, very minimum haze. After a month, you see that there is something on the cornea, but you can't call it haze, and then it vanishes by three to six months," he says. "However, you get more haze when the regrowth of the epithelium takes longer, so it's important that the stroma is covered with epithelium as much as possible after the procedure."

"For me, Epi-LASIK is a clear improvement over PRK and LASEK," asserts Dr. Dick. "But this has to be proven by randomized studies. And, of course, we had a limited number of cases without long-term follow-up. Even so, I've learned that it's a very short learning curve for the surgeon familiar with LASIK or LASEK, and we had no intraoperative complications."

"I think Epi-LASIK will improve," says Dr. Mertens. "The epi-keratome is still one-size-fits-all, with a single diameter ring size and so on, as opposed to LASIK, which has different ring sizes and cutting heads. We also have to learn how to handle the epithelial flap better, decide which contact lens is best and determine which drops are better postop."