Incidence

Although there is a lower incidence of uveitis in children, the rate of visual loss may, in fact, be worse than that of adults. Uveitis in the pediatric population is a serious concern for ophthalmologists and pediatricians, given the greater life span of children and potential long-term disability from vision loss.

The incidence of childhood uveitis per year is estimated to be 4.3 to 6.9/100,000 in North America and Europe, while the incidence of adult uveitis is estimated to be 26.6 to 102/100,000. The prevalence of pediatric uveitis is about 30 cases in 100,000 versus 93 in 100,000 in adults.1-5

Major changes in the pattern and anatomic distribution of uveitis have occurred since early studies were reported in the 1960s. Noticeable changes occurred over the last decade, including the rise in the amount of panuveitis and the decrease in posterior uveitis, happening presumably due to a decrease in toxoplasmosis and toxocariasis in children in developing countries. Idiopathic uveitis remains the most common diagnosis, despite the increasing sophistication of diagnostic techniques and, possibly, autoimmunity in the population.6

It is not easy to obtain reliable data. Although most data suggest that uveitis has increased, the cause of the increase is unknown. Hopefully, it is only a reflection of better surveillance and the fact that eye doctors are diagnosing uveitis more quickly.

Etiology

Ophthalmologists are familiar with the challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric uveitis. Children can have the condition and not be aware of it because uveitis does not produce noticeable symptoms, such as light sensitivity or red eye. This often leads to late presentation to the ophthalmologist and frequently pathology is already established and a significant amount of visual acuity has been lost. Other challenges include obtaining a history and examining the children.

Numerous causes for pediatric uveitis exist. They include the classical broad categories of: trauma—intraocular foreign body (rare); cancer (rare), autoimmune disorders (by far the most common); and infectious origins (second most common).

|

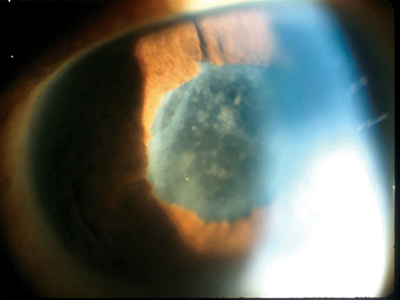

| Figure 1. Active uveitis, with posterior synechiae and with fibrin and cells on the anterior lens capsule. |

With regard to autoimmune disorders, uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common. Other endogenous syndromes associated with uveitis include: Kawasaki syndrome; chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular/neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease syndrome; sarcoidosis; HLA-B27-associated uveitis; tubulonephritis and uveitis syndrome; psoriasis; enteropathic associated uveitis; and familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis.

Foster Study

Our recent study of a 269 children with uveitic syndromes found that uveitis remains a serious cause of morbidity and visual loss in children. Timely referral to uveitis specialists may lead to improved visual outcomes in children with chronic uveitis.6

Our retrospective cohort study analyzed demographics, anatomic data, diagnoses, systemic associations, and visual outcomes of pediatric patients referred to me from 1985 to 2003. After retrospectively reviewing the records of 1,242 patients with uveitis, 269 patients 16 years and younger were identified.

Results

Among the 269 children with uveitis, 53.5 percent were girls, 82 percent were Caucasian, and 82 percent were born in the United States. The type of uveitis varied: anterior uveitis (56.9 percent of cases); intermediate (20.8 percent); panuveitis (16 percent); and posterior (6.3 percent). The most frequent type of inflammations were: nongranulomatous (77.6 percent) and noninfectious (85.7 percent). The process was bilateral in 74.4 percent of patients. Mean follow-up was 22 months, with mean age of 8 years at diagnosis. Mean duration of uveitis at the time of presentation to me was two years.

The time between the diagnosis of uveitis and referral ranged from one day to 5.6 years. The length of time between diagnosis of uveitis and the referral to a uveitis specialist strongly correlated with the complication rate and degree of visual impairment in our study. In other words, the longer the time before the patients were seen by the uveitis expert, the worse the visual outcomes.

No systemic associations were found in 58 percent of patients. JIA was responsible for 33 percent of cases, 8 percent of patients had other systemic associations, and 1 percent had tubulointerstitial nephritis uveitis syndrome.

Complications

Uveitis is a major cause of vision loss. The best available data indicate that 12 percent of children with JIA-associated uveitis eventually have profound loss of vision. However, it may take many years to get to that point. The child's vision loss doesn't appear so bad in the short term, and loss is incremental. However before the eye doctor may realize, the child is not seeing adequately and has developed a cataract or some even more serious source of vision loss, such as maculopathy, from chronic uveitis. The slow "dance" with the steroids can be quite seductive.

|

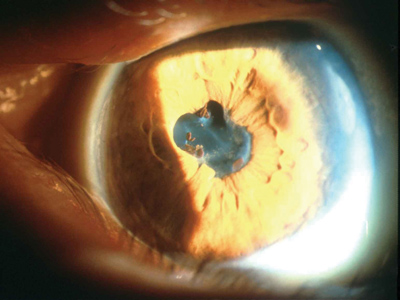

| Figure 2. Inactive uveitis, quiet for three months, ready for cataract surgery. Posterior synechiae are present, as is a pupillary membrane. |

Complications of pediatric uveitis include band keratopathy, glaucoma, phthisis, cataract formation, macular edema, and optic nerve problems. In our current study the rates of complications were lower. This is possibly due to the short mean follow-up period (22 months) compared to other similar studies; however, we believe that it is, more likely than not, a consequence of our more therapeutically aggressive approach to the problem, and our intolerance to endless steroid therapy.

|

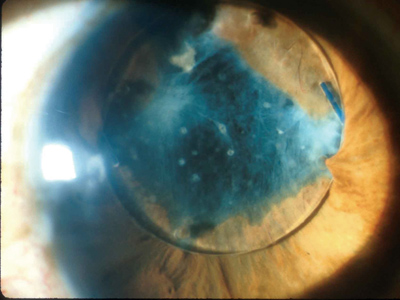

| Figure 3. This patient has a long history of recurrent uveitis, and the uveitis was successfully placed into remission with systemic immunomodulatory therapy. Cataract surgery was then performed, and it was uncomplicated. A posterior chamber lens implant was used, and this turned out to be a mistake in judgment, with lens intolerance by this eye. After one year of multiple YAG laser sessions for membrane and lens deposit removal, it is now clear that this lens implant should be removed and the patient left aphakic. The chronic inflammation and membrane formation has dragged the lens optic into the pupil and has produced intractable macular edema. |

Uveitis and Referral

Eye doctors are becoming more and more aware of the importance of screening even very young children by slit-lamp examination. In addition, they are recognizing the importance of moving a child with JIA-associated uveitis along to a uveitis specialist very early in the course of events instead of repeatedly treating with steroid drops as was done frequently in the past.

Treatment for pediatric uveitis by the general ophthalmologist includes a general diagnostic work up and then administration of a substantial number of corticosteroid eye drops each day to quiet the eye. Drops then are tapered to full discontinuation. If the uveitis flares up again, I recommend that the eye doctor immediately make the referral to the uveitis specialist. Some eye care physicians, however, may choose to refer the pediatric patient for the initial treatment. In general, the chronicity of uveitis is a tip-off that the patient should consult a uveitis specialist.

Early Detection

Uveitis can begin in infancy. Our study included large numbers of children between 2 and 7 years old. This age group faces another hurdle. If vision is damaged and a cataract develops, then it is only a matter of time until the development of amblyopia.

If the child does not receive treatment promptly so he can obtain a good formed image on the retina of that eye that is affected, then he will be deprived of good formed images during the formative years when the neuroconnections are being made. If the uveitis and cataract problems are resolved later when the child is 11 or 12-years old, the child may still have a lifetime of poor vision because of the inevitable and irreversible lazy eye or amblyopia.

|

Future Implications

The key to earlier and earlier detection is legislation. Activists like Jean Ramsey, MD, of Massachusetts, have become involved with their state legislators and have effectively brought legislation to the forefront that mandates vision screening for young preschool children. Through their work, they have found the resources to pay for the devices used for vision screening and set up the appropriate training for screeners. It is a big challenge, but it is a challenge worth meeting (See sidebar, p. 38).

|

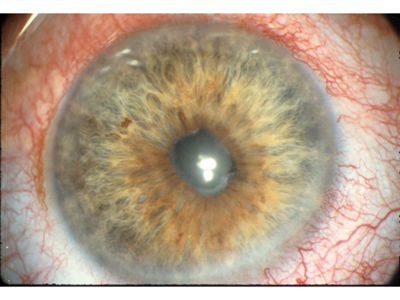

| Figure 4. Uveitis, active, and not ready for cataract surgery. Note the posterior synechiae, the pupillary membrane and the ciliary flush superiorly. |

Because of such early vision screenings, the child whose uveitis (or other visual problem) would have been detected at age 8 now can be detected at age 3, when something can be done before permanent damage sets in. This legislation is a boon to ophthalmologists and to the population at large. It is going to be one of two critical elements of driving down the prevalence of blindness caused by pediatric uveitis. The other element is earlier referral of chronic uveitis patients to a uveitis specialist who is prepared to use drugs other than steroids.

By working together and following through on these two critical elements we can best preserve the health and vision of young patients with chronic uveitis.

Dr. Foster is the founder and president of the Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation at the Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institute, in Cambridge, Mass. He is also a clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School. For more information visit uveitis.org.

1. Gritz, DC. Wong IG Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California: The Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology 2004;111:491-500.

2. Edelsten C, Reddy MA, Stanford MR, Graham, EM. Visual loss associated with pediatric uveitis in English primary and referral centers. AM J Ophthalmol 2003;135:676-80.

3. PaivÖnsalo-Hietanen T, Tuominen J, Saari KM. Uveitis in children: population-based study in Finland. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000;78-84-8.

4. Darrell, RW, Wagener HP, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of uveitis. Incidence and prevalence in a small urban community. Arch Ophthalmol 1962;68:502-14.

5. Kimura SJ, Hogan MJ, Thygeson P. Uveitis in children. Arch Ophthalmol 1954;51:80-8.

6. Kump L, Cervantes-Castañeda R, Androudi S, Foster CS. Analysis of Pediatric Uveitis at a Tertiary Referral Center. Ophthalmology 2005;112:1287-92.