Surface ablation continues to maintain a strong foothold in an increasingly competitive refractive surgery field. Some surgeons use the procedure more than in the past or even exclusively, arguing that today’s advanced technology can make visual recovery faster, postop pain more manageable and complications easier to prevent, positioning this pioneering form of laser vision correction for growth and enduring success. As with most procedures, this one requires the skilled hands and eyes of knowledgeable, experienced and committed surgeons.

Have you considered the latest advantages of surface ablation when you plan your procedures? In this article, your peers explain how they succeed while meeting the familiar challenges of surface ablation—selecting appropriate patients, effectively debriding the corneal epithelium, managing postop pain and minimizing unwanted outcomes.

One and Only

Leading surgeon Marguerite McDonald, MD, FACS, the first to perform a surface ablation procedure when she completed PRK with an excimer laser at Louisiana State University on March 25, 1988, has now returned to her roots, performing only surface ablation procedures.

“I’ve done PRK, EBK, LASEK, Epi-LASIK and—for many years—LASIK. Everything short of SMILE, for which I’m awaiting further refinements,” says Dr. McDonald, clinical professor at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City. “Today, with modern surface ablation, I get virtually the same result as with LASIK. I achieve exquisite outcomes, quick recovery and virtually no pain. Plus, I don’t have to worry about flap complications.”

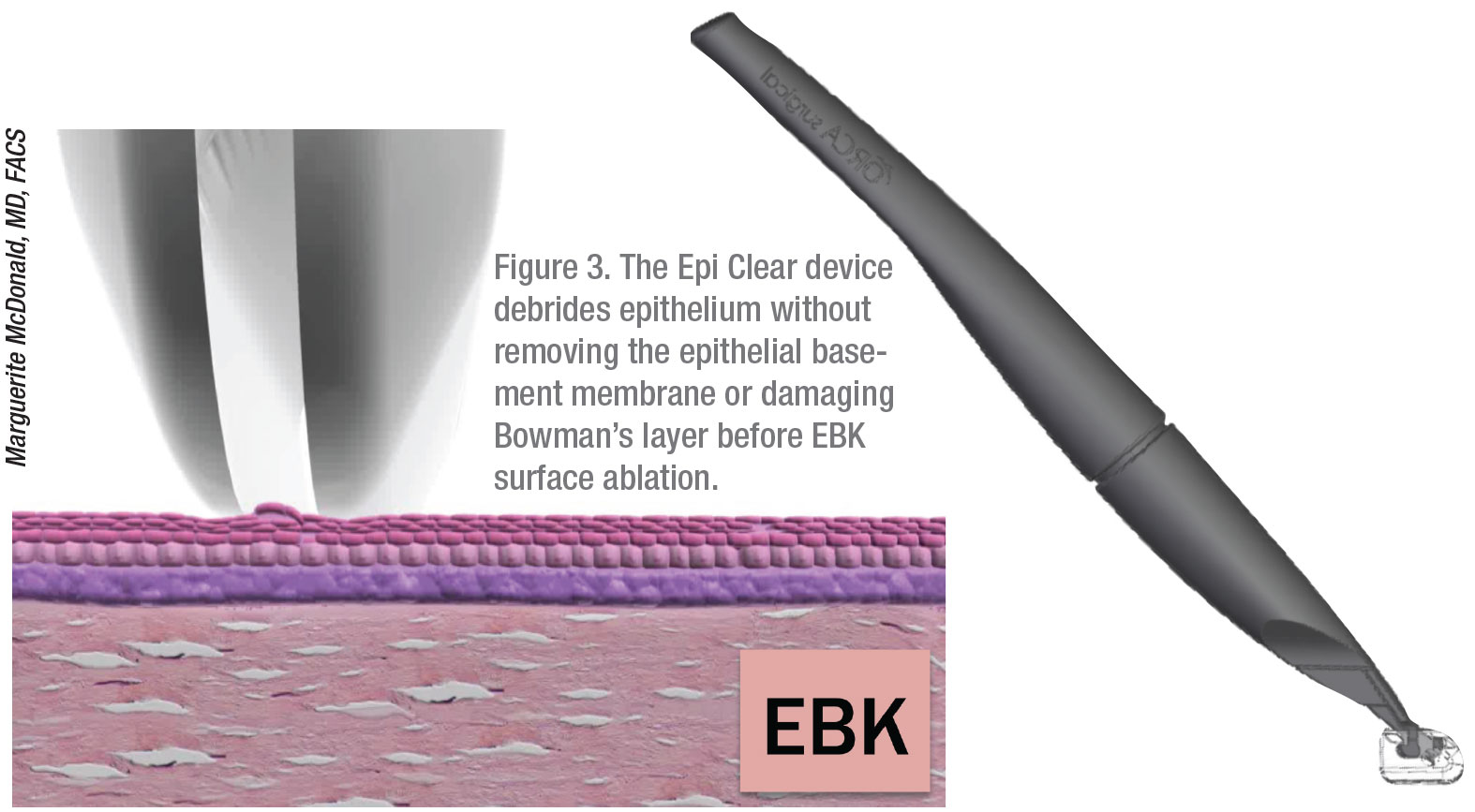

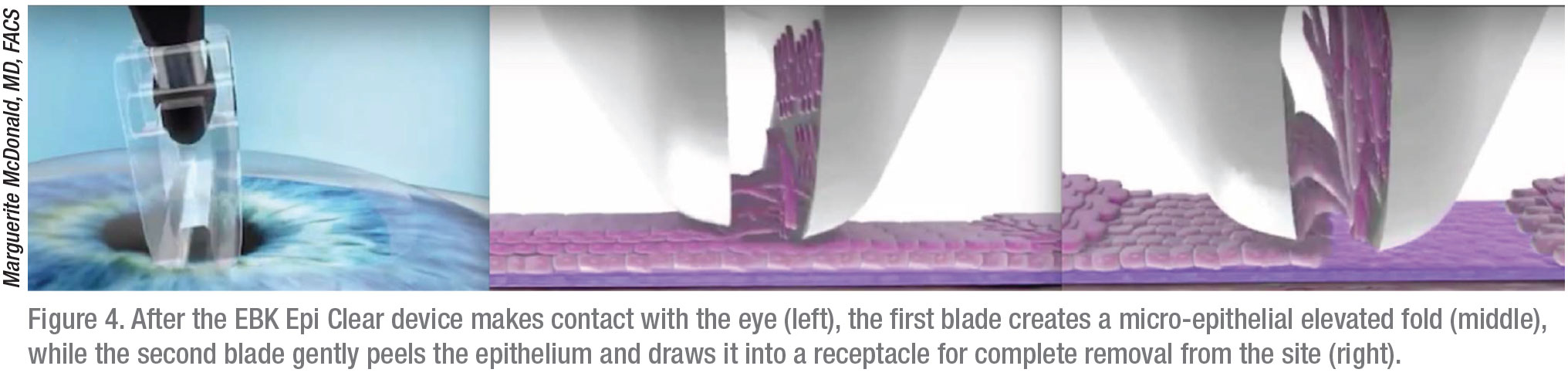

To achieve these results, Dr. McDonald exclusively uses Epi-Bowman Keratectomy (EBK), performed with the Epi Clear device (Orca Surgical, Israel). Before ablating the cornea with a Visx laser, she relies on the first “blade” of the Epi Clear device to create a micro-epithelial elevated fold, while letting the second blade gently peel the epithelium and draw it into a receptacle for complete removal from the site without touching the epithelial basement membrane or Bowman’s layer. “If you take your time, you can lift up the epithelium in sheets, which is much more effectively done with the EBK technique,” she says.

Norfolk, Virginia, surgeon Elizabeth Yeu, MD, takes a different approach to surface ablation. “I would say 15 percent of my procedures are PRK and 85 percent, LASIK,” she says. “I think advanced surface ablation provides us with a wonderful way to take care of our patients who may have marginal corneal thickness, a tendency toward more clinically significant dry-eye disease or who just shouldn’t be getting flap surgery,” she adds.

Rachel Epstein, MD, a refractive surgeon at Chicago Cornea Consultants, says she also offers PRK when surface ablation is indicated. “We probably perform a 50/50 split between LASIK and surface ablation,” she says. “We’re still exploring the possible implementation of SMILE into the practice. We have a very large referral base that includes patients with keratoconus and corneal ectasia. I think we’re uniquely attuned to the prevention of post-LASIK ectasia. With the use of Pentacam scans or even clinical evaluation, I find far too often that PRK is a safer option. It’s a procedure we were doing long before LASIK and a procedure we continue to do even with the availability of LASIK, so that speaks to its longevity.”

Edward Manche, MD, division chief of the cornea and refractive surgical service at Stanford University School of Medicine at Byers Eye Institute, says 90 percent of his practice involves refractive surgery procedures, including 15 percent via surface ablation.

“I typically perform PRK in patients who may not be suitable for LASIK or SMILE surgery,” he says, echoing the strategy of many of his colleagues. “The most common indication is for patients with thin corneas (i.e., less than 490 µ). I use the standard exclusion criteria for LASIK—ruling out patients with some autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, etc. I also exclude eyes with ectactic disorders, such as keratoconus and pellucid marginal degeneration, from undergoing LASIK.”

|

Why Surface Ablation?

LASIK, producing minimal postop pain and rapid vision correction, emerged as the darling of laser refractive procedures at the turn of the century, when 1.4 million patients underwent the procedure in the United States in 2000. However, the number of procedures dropped to 749,000 in 2009, following the recession of 2008.1,2 Besides the bad economy, a limited number of poignant complaints about LASIK complications and a well-publicized federal hearing held for distraught patients and their families on April 25, 2008 were blamed by some for the downturn in the number of LASIK procedures.3,4,5

The appearance of competing refractive surgery procedures—such as LASEK, Epi-LASIK, conductive keratoplasty, phakic IOLs, refractive lens exchange and SMILE—gave surgeons more options, and this has created opportunities for procedures that perform well.

“I’ve tried the newer surface ablation procedures, LASEK (ethyl alcohol [EtOH]-assisted laser-assisted subepithelial keratectomy)6 and Epi-LASIK (epithelial laser in situ keratomileusis),7 and I’ve found that PRK is superior,” says Dr. Manche.

During LASEK, a trephine is used to cut and lift a flap of epithelial corneal tissue to treat low myopia. An EtOH-based solution is used to loosen the epithelial cells. Once the epithelial flap is created and moved aside, the procedure is the same as PRK. “After the laser treatment, you’re supposed to lay the flap of epithelium back in place,” says Dr. Manche. “But that amounts to putting dead epithelial tissue back. The new epithelial cells need to reproduce under this dead tissue, which doesn’t seem to make sense. Nobody is doing that procedure anymore.”

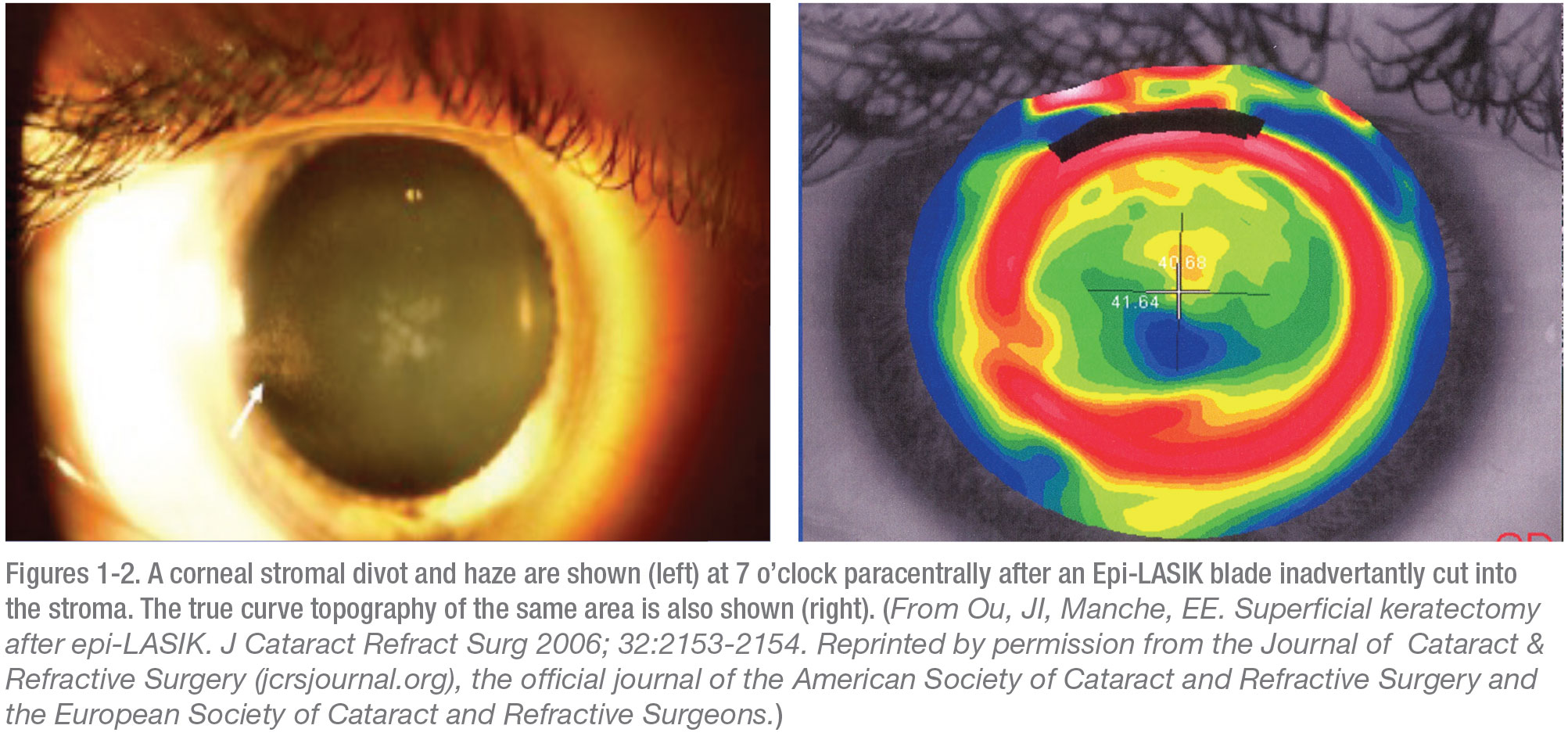

Epi-LASIK, the other newer surface ablation method, involves the use of a special microkeratome called the Epi-keratome. “This technique was abandoned because every once in a while, even with the dullest of plastic blades, the blade would evulse a little chunk of stroma, which can create a significant decrease in vision if it happens over the visual axis,” points out Dr. McDonald.

“We published a case report in which we had the Epi-LASIK blade cut into the stroma and the result was a really bad outcome,”8 adds Dr. Manche. (See Figures 1-2.) “This is another procedure that has never taken hold.”

Division Over Debriding

One of the critical techniques involved in surface ablation—over which many surgeons respectfully disagree—is debriding the epithelium. Dr. Yeu says she’s comfortable using an Amoils brush for naïve corneas and EtOH wells for enhancements. Dr. Epstein is also comfortable with EtOH. “One of my associates and I prefer to debride the epithelium with alcohol, while another associate prefers the Amoils brush,” she says.

However, Dr. Manche, who debrides with a mechanical brush, only uses EtOH to debride when he needs to avoid disrupting the corneal surface of post-LASIK and post-radial keratectomy patients while preparing these patients for follow-up PRK. “I’ve seen cases where the alcohol affects areas differently than we’d hoped, and we’ve seen a little bit of an irregular ablation in some patients,” he says.

|

Avoiding the use of EtOH to debride the cornea is one of several reasons Dr. McDonald uses EBK. “Published studies show that EBK’s outcomes are superior, and the amount of discomfort is significantly less, than with standard PRK,” she notes.9,10 “Any time you have to remove epithelium, it will re-epithelialize faster and the patient will be more comfortable if you’re using the EBK technique versus an alcohol-soaked/alcohol-containing device—which has been shown to be toxic to the epithelium11,12—or other instruments, such as a Tooke knife and the Amoils brush. (See Figure 3 and Figure 4.)

“Surgeons can also use the Epi Clear device to perform pterygium surgery or clean up the edges of an indolent non-healing corneal ulcer,” Dr. McDonald continues. “With EBK, you never accidently damage the stromal tissue. In fact, you also spare the epithelial basement membrane and Bowman’s layer.”

She notes that the use of the Amoils brush, EtOH or transepithial PTK to debride the epithelium ruptures the epithelial cell walls, “causing pro-inflammatory cytokines to pour into the stroma and initiate an inflammatory cascade. Basement membrane is also removed.”

In the past, before improved laser technology enlarged ablation zones, Dr. Manche’s preferred method of debriding the epithelium was to use transepithelial phototherapeutic keratectomy (T-PRK) before PRK.

“This is a feature on the Visx excimer laser,” he says. “You could remove 6.5 mm of epithelium, allowing it to be perfectly centered, using autotracking and autocentration. In my opinion, it’s best to remove exactly the right amount of epithelium, allowing the fastest rate of re-epithelialization. T-PRK uses a very sharp edge, so the cells grow back immediately, as opposed to when you use EtOH, a brush or mechanical scraping.

“We were once able to get eyes re-epithelizing in 24 to 36 hours. Unfortunately, with the development of larger treatment treatment zones, up to 8 or 9 mm, debriding with T-PRK isn’t viable at this time.”

Dr. Manche hopes an enlarged T-PRK target zone will be introduced in the United States with a new technology, such as the type used by Schwind Eye-Tech Solutions in Germany.

“That’s something that would definitely be welcomed by surgeons in the U.S.,” he says.

|

Improved Technologies

No matter which debridement method you use, Dr. McDonald points to improved technologies as a primary motivation in her restored commitment to surface ablation.

“Before flying spot lasers, we had the wide beam lasers with the diaphragm opening or closing,” she recalls. “As a result, more patients experienced haze and regression due to the rough surfaces created by the ablation. Now our laser treatments are so incredibly smooth that haze is really a non-issue, unless you attempt to remove too much tissue. Most surgeons stop at approximately 8 D of myopia.

“For virtually every patient, I use the Visx laser to do custom wavefront EBK,” Dr. McDonald continues. “The only time I wouldn’t consider this approach is if I were trying to touch up a multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus IOL, when you want to get patients closer to plano at distance. If you attempt to do a wavefront-guided procedure on these patients, you risk reversing the multifocality of the IOL.”

Wavefront-guided treatment, which has improved the precision of LASIK, has benefited surface ablation equally, according to Dr. McDonald. “Higher-order aberrations and astigmatism are well-treated now with this technology,” she says. “Topography-guided treatments also effectively treat highly-aberrated eyes, as you may find in a patient who’s had a corneal transplant. The early results are good, although we’re still refining those treatments.”

Dr. Yeu uses the WaveLight Allegretto Wave Eye-Q excimer laser (Alcon) for patients who don’t need significant cylinder correction. “I also use the Contoura Vision topography-guided system (Alcon) to individualize the treatment of patients who have higher amounts of astigmatism,” she adds.

Dr. Manche says he has three excimer lasers, including a Star S4 IR Excimer Laser (Johnson & Johnson), Alcon’s Allegretto system and a MEL 90 excimer laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec), awaiting FDA approval. “We also have an Intralase iFS Advanced Femtosecond Laser (Johnson & Johnson Vision) and a VisuMax femtosecond laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec),” he says. “I do all of my wavefront-guided treatments (both LASIK and PRK) on the Visx CustomVue system. My topography-guided treatments (both LASIK and PRK) are performed on the Allegretto Contoura system. I also use the Allegretto system for my wavefront-optimized treatments (both LASIK and PRK).”

And the breakdown of his cases? “I use wavefront-guided treatments in 95 percent of my PRK and LASIK cases,” he says. “About 5 percent of the remaining cases are performed using topography-guided ablation, with only occasional use of wavefront-optimized ablations, which I most commonly provide when offering LASIK or PRK to pseudophakic multifocal IOL patients with residual refractive errors.”

Dr. Manche says he achieves equal results with of all of his refractive surgery procedures. “The meta-analysis shows nearly identical outcomes,” he notes. “We’ve done LASIK in one eye, PRK in the other eye. The outcomes are identical from the patient’s perspective. We look at wavefront-guided in one eye and optimized in another, and we get the same results, as we do with PRK. You can find minor differences when looking at the results, such as higher-order aberrations. But when you ask patients which eye is better, they can’t tell.”

In Chicago, Dr. Epstein uses the Alcon/WaveLight EX500 laser for all of her refractive surgery patients and the Johnson & Johnson iFS femtosecond laser to create LASIK flaps. “We use this laser for LASIK and PRK,” she says. “We’ve been implementing Dr. Mark Lobanoff’s Phorcides planning software to both identify and treat astigmatism, utilizing some of the most advanced technology. This software allows for both Contoura and wavefront-optimized treatment planning.”

Managing Pain

Of course, the least desirable aspect of surface ablation procedures is postop pain. But it’s getting better.

Dr. Manche uses an AcuVue Oasys plano lens with a base curve of 8.4 postop. “It helps to have a relatively tight lens to reduce pain,” he observes. “I use one drop of an NSAID at the conclusion of PRK surgery, and I treat patients with a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone antibiotic and topical steroids to control infection and pain. We also use oral NSAIDS (ibuprofen) and either hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen (oral Vicodin) or acetaminophen/hydrocodone (Norco) for rescue relief.”

Dr. Manche’s PRK patients typically undergo the procedure on a Thursday because pain usually doesn’t develop until inflammation peaks 48 to 60 hours after the procedure. “By Saturday, most of them have burning, tearing and light sensitivity,” says Dr. Manche. “Some patients don’t use any pills for rescue relief. Others go through the whole bottle. Because we’re using the larger ablation zones of wavefront-guided and topography-guided lasers, we’re exposing more corneal nerve endings, so it takes longer for the pain to diminish while these larger defects re-epithelialize. However, the contact lenses and nonsteroidal drops are better these days, so that helps a lot.”

Based on research, Dr. McDonald has developed an effective postop pain control regimen for surface ablation. Below are the treatments she recommends:

• vitamin C 500 mg, twice a day by mouth, beginning the day surgery is scheduled, to help with corneal healing;13

• topical cyclosporine, b.i.d., begun immediately postop and continuing for three months, whether or not patients have dry eye;14

• rapidly-tapering oral steroids for healthy, nondiabetic patients, including eight 10-mg tablets taken under her supervision precisely 30 minutes before surgery, eight 10-mg tablets the first postop day, four the second postop day, two the third postop day, one the fourth postop day and one-half of a tablet the fifth postop day. “I also put them on ranitidine (Zantac), p.o. 150 mg b.i.d for six days to protect against gastritis,” she notes;

• loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel (Lotemax SM 0.38%) or prednisolone acetate (Pred Forte), four times a day for seven days, starting on the day of surgery;

• besifloxacin (Besivance, Bausch + Lomb) or ofloxacin (Ocuflox, Allergan), four times a day for seven days, starting on the day of surgery;

• ketorolac tromethamine ophthalmic solution (Acuvail, Allergan) up to four times a day for three days, as needed for pain;

• “comfort drops” from a specialty pharmacy that includes 0.1% tetracaine, one drop up to every hour for pain during the first three postop days;

• preservative-free tears, every two hours while awake;

• Refresh Celluvisc (Allergan), one drop at night until the patients’ bandage contact lenses are removed at five to seven days, after they’ve worn them 24 hours a day for a week;

• over-the-counter Retain PM ointment (Ocusoft) when the contact lenses are removed, applied every night at bedtime until the one-month postop visit;

• over-the-counter, extra-strength acetaminophen tablets (Tylenol);

• Vicodin, 5 mg/300 mg, four to six tablets, for rescue relief;

• ice packs on the patient’s eyes for 10 minutes after surgery, under Dr. McDonald’s direction, then as much as possible at home during the first 24 hours postop.

Although Dr. McDonald thinks about cutting down her pain-control protocol because of EBK’s pain-sparing benefits, she continues with the therapy. “When patients return to the office, their eyes are open, white and they’re smiling,” she says. “They’ve taken a shower. They’re comfortable.”

To ward off postop pain, Dr. Yeu prescribes ketorolac tromethamine (Toradol), 10 mg daily, for three days, and uses a compounded dilute topical lidocaine drop and oral tramadol, as needed, for rescue relief.

|

“For our PRK patients, if mitomycin-C is used, I rinse the surface thoroughly with two bottles of very chilled BSS and place an appropriately sized bandage contact lens made of appropriate material after treatment,” says Dr. Epstein. “I also place a drop of homatropine, which we’ve found improves patient comfort. I generally give a very small amount of an oral painkiller, typically Vicodin, to use as needed, with the caveat that they first must try an over-the-counter NSAID. I also prescribe a topical NSAID, to be used during the first 48 hours postop. We also stress the importance of very frequent lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears, especially in the immediate postop period.”

Preventing Ectasia

Surgeons also report progress in steering clear of thin corneas, a challenge in all refractive surgery procedures. Choosing the right patients for treatment is an obvious key to success.

“One of the areas where we have improved during the past decade or so is in our ability to properly screen and exclude patients who may be at higher risk for ectasia,” says Dr. Manche. “The key is prevention. Sometimes, though, we don’t find out about this problem until after surgery. In the rare cases where you do see ectasia postop, we now of course have the ability to offer corneal cross-linking.”

Dr. McDonald says identifying ectactic conditions is critical when evaluating questionable preop patients. “Surgeons choose surface ablation when the cornea is too thin or the patient appears to possibly have keratoconus,” she observes. “They’re afraid to do LASIK in these cases, but they’ll go ahead and do PRK. Well that, in my opinion, is a bad idea. In other words, if somebody looks like they have keratoconus, or a corneal thickness that’s below 512 µm, I would not recommend laser vision correction.15 I’ve had every possible complication you can have in refractive surgery, but I’ve never had ectasia because I’m conservative and I’ve always followed those few simple rules.”

Because of the extensive preop evaluation performed in Dr. Epstein’s practice, she says she has only seen ectasia in a handful of cases. “However, we do see a fair number of outside referrals for post-LASIK ectasia, generally in patients who underwent LASIK five-to-10-plus years ago,” she says. “We typically recommend corneal collagen cross-linking and specialty contact lens fitting for these patients.”

Dr. Epstein notes that her practice is investigating the potential for combined treatment of corneal collagen cross-linking and PRK for certain subsets of patients with keratoconus. “But generally, we avoid refractive procedures in patients with unstable refractions, abnormalities on Pentacam (posterior elevation, displaced apex), history of ocular herpetic disease, uncontrolled ocular surface disease and corneal endothelial dystrophy, as well as patients who are planning to become or are currently pregnant and breastfeeding.”

Fewer Unwanted Outcomes

“With our modern technology, we have fewer induced higher-order aberrations,” says Dr. Manche. “If you use wavefront- or topography-guided systems, you can improve those symptoms. Also, because of larger treatment zones, patients experience fewer night vision issues, such as glare and halos.”

Dr. Manche notes that advanced technology allows you to effectively treat induced or residual astigmatism from a previous refractive procedure. “We were able to do it in the old days, but now we have lasers that are much more accurate. We’ve come a really long way because of iris registration, autocentration and tracking.”

|

Dr. Epstein says she’s found the Phorcides software to be a useful tool for both preventing and treating higher-order aberrations and astigmatism. “I employ that technology in both our primary and secondary treatments, where applicable,” she notes.

Better strategies are also now available in the event of postop haze. When a postop patient develops haze, Dr. Epstein starts with a topical steroid—Durezol, if possible—to determine how much improvement she can achieve with medical management.

“I’m very careful to monitor IOP in these patients,” she says. “If medical management doesn’t provide us with a satisfactory degree of improvement, I’ll recommend superficial keratectomy, followed by application of 0.02% mitomycin-C to the stromal bed for two minutes. This may have to be repeated. I typically wait to treat residual refractive error until we’ve adequately addressed the haze.”

Dr. McDonald takes postop precautions to avoid haze and regression. “I tell surface ablation patients to wear UV-blocking sunglasses whenever they’re outside, for at least the first year, though we really don’t know how long the ‘plastic period’ lasts, during which UV light can cause haze and regression,” she notes. “We do know that if you expose these eyes to significant amounts of direct sunlight during the early postop period, you can cause haze and regression.”

If patients return to Dr. McDonald with postop haze, the prognosis is good. “Most of the time, if you just give steroid drops q.i.d. for a week or two and then wait, it’ll go away,” she says. “Even with a referral practice, however, it’s been a long time since I’ve had to physically remove the hazy tissue with a Tooke knife or EBK. It’s been years since I’ve seen a patient who needed the prior two-step procedure—haze removal followed three months later by a laser retreatment. It just doesn’t happen anymore.”

Dr. Yeu encounters other postop issues. “Besides excessive sun exposure, I also see haze from poor adherence to topical steroids,” she notes. “Higher-diopter treatments (more than 5 D) can also have the tendency to raise potential issues. I turn to mitomycin-C 0.02% for six to 12 seconds—and for longer periods for higher-power treatments and retreatments (such as after I am performing PRK over LASIK).”

In Search of Perfection

Despite the progress surgeons have made in surface ablation procedures, they’re quick to say there’s room for improvement. “If you customize care for each patient and respond to their needs with the latest information in mind, you should do well with surface ablation,” says Dr. McDonald. “Our surface ablation outcomes are much better now, in every way, and they’ll only continue to improve.” REVIEW

Dr. McDonald is a consultant to Orca, the makers of the Epi-Clear device. Dr. Yeu consults with Alcon, Allergan, Bausch+Lomb/Valeant, J & J Vision, Merck, Novartis, Ocular Science, Ocular Therapeutix, OcuSoft, Shire, Sight Sciences, Sun Pharma, Topcon, and Zeiss. Dr. Manche is a consultant for Allergan, Avedro, Zeiss and J&J Vision. He provides sponsored research for Allergan, Alcon, Avedro, Zeiss, J&J Vision and Presbia. He owns equity in RxSight and Vacu-Site. Dr. Epstein reports no relationships.

1. Statista.com https://www.statista.com/statistics/271478/number-of-lasik-surgeries-in-the-us/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2020.

2.WebMD.https://www.webmd.com/eye-health/news/20180727/lasik-know-the-rewards-and-the-risks Accessed Jan. 14, 2020

3. Feder B. As economy slows, so do laser eye surgeries. New York Times, Business Day, April 24, 2008. nytimes.com/2008/04/24/business/24lasik.html Accessed Jan. 14

4. Associated Press. Witnesses Tell of Suffering After Lasik. New York Times, Business Day, April 25, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/25/business/aplasik-web.html

5. Stein JD, Childers DM, Nan B, Mian SI. Gauging interest of the general public in LASIK eye surgery. Cornea 2013;32:7:1015-8.

6. Camellin M. Laser epithelial keratomileusis for myopia. J Refract Surg 2003;19:6:666-70.

7. Pallikaris IG, Katsanevaki VJ, Kalyvianaki MI, Naoumidi II. Advances in subepithelial excimer refractive surgery techniques: Epi-LASIK. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2003;14:4:207-12.

8. Ou JI, Manche EE. Superficial keratectomy after epi-LASIK (correspondence). J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:12:2153-4.

9. Vingopoulos F, Kanellopoulos AJ. Epi-Bowman blunt keratectomy versus diluted EtOH epithelial removal in myopic photorefractive keratectomy: A prospective contralateral eye study. Cornea 2019;38:5:612-616.

10. Taneri S, Kießler S, Rost A, et al. [Epi-Bowman Keratectomy: Clinical evaluation of a new method of surface ablation]. [Article in German] Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2018;235:12:1371-1382.

11. Fattah MA, Antonios R, Arba Mosquera S, et al. Epithelial erosions and refractive results after single-step transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy and alcohol-assisted photo refractive keratectomy in myopic eyes: A comparative evaluation Over 12 Months. Cornea 2018;37:1:45-52.

12. Zhang P, Liu M, Liao R. Toxic effect of using twenty percent alcohol on corneal epithelial tight junctions during LASEK. Mol Med Rep 2012;6:1:33-8.

13. Chen J, Lan J, Liu D, et al. Ascorbic acid promotes the stemness of corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells and accelerates epithelial wound healing in the cornea. Stem Cells Transl Med 2017;6:5:1356-1365.

14. Salib GM, McDonald MB, Smolek M. Safety and efficacy of cyclosporine 0.05% drops versus unpreserved artificial tears in dry-eye patients having laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:5:772-8.

15. Randleman JB, Dupps WJ Jr, Santhiago MR, et al. Screening for Keratoconus and Related Ectatic Corneal Disorders. Cornea 2015;34:8:e20-2.