Initial Therapy

Here are the steps physicians take when managing a newly diagnosed uveitis patient.

First, physicians say to first make sure that you’re dealing with a non-infectious uveitis. “My general approach is to first rule out infection with some targeted lab testing based on the patient’s history and ophthalmic exam,” explains Sam Dahr, MD, chairman of ophthalmology at Integris Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City. “Once I feel that there’s a reasonable chance that it’s not infectious, I’ll perform a trial of oral corticosteroids, and I’ll follow the patient especially closely for the first two weeks. If the patient worsens, I’ll then try harder to figure out if there is some sort of occult or atypical infection that I’m missing.”

Since pan-uveitis is the only variety that involves some anterior-segment inflammation, for these patients experts take steps to quiet the anterior inflammation first. “I first manage the anterior aspect of the disease, iridocyclitis, with aggressive topical therapy,” says Glenn Jaffe, MD, chief of retina at

|

| After ruling out infection, physicians usually begin treating uveitis with corticosteroids, though they have a low threshold for upping the ante to immunosuppressive drugs. |

Dr. Dahr notes that physicians say the initial therapy almost always involves some corticosteroid therapy, and Dr. Jaffe agrees with that assessment. “For almost all the types of uveitis, the initial therapy usually will be corticosteroids in one form or another,” Dr. Jaffe says. “If, in addition, or as an alternative, I have made a decision to treat the patient with immunosuppressive therapy, I tailor the immunosuppressive therapy to the specific type of uveitis. It’s important to remember that uveitis is a group of diseases—not one specific disease. Therefore, the treatment isn’t a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

“For uveitis that affects the posterior segment, the first decision point is whether to use systemic or local corticosteroids. If the patient has bilateral disease or if they have disease that has a systemic component that would do well with corticosteroids, then I’m more likely—at least initially—to treat with systemic steroids, namely prednisone,” Dr. Jaffe continues. “Again, the dose I’d start with depends on the particular condition, and it’s usually in the neighborhood of 1 mg/kg/day, but will vary depending on the type of uveitis, as well as some patient factors. For example, some patients may not be able to tolerate systemic corticosteroids, such as a diabetic patient about whom you’d worry that you might worsen the diabetes with the steroid treatment; or a hypertensive patient. If they have asymmetric or unilateral disease, and they don’t have a systemic disease component that would do well with prednisone, or they are not likely to tolerate systemic corticosteroids, then I’d be more inclined to start local therapy. Local therapy options would include a posterior sub-Tenon’s steroid injection or intravitreal steroids. However, I usually start with a posterior sub-Tenon’s injection. I can always go to an intravitreal injection later, if needed. As retinal specialists, we are almost programmed to treat people with intravitreal injections, but with a uveitis patient you can often achieve the treatment you need with a periocular steroid injection, which has the advantages of less risk for endophthalmitis and/or an increase in intraocular pressure. Having said that, though, if the inflammation is severe, or if the patient doesn’t respond to a periocular steroid injection, I’d use an intravitreal steroid.” For the intravitreal steroid route, Dr. Jaffe says that, at this point in the therapy, he prefers either an intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide (1 mg in 0.1 ml) or a short-acting sustained drug delivery system such as Ozurdex (dexamethasone implant), which lasts six weeks to three months.

• Why steroids first? Though there are several powerful drugs and drug delivery systems that can be brought to bear in uveitis, an initial course of steroids is considered the most prudent. “There are two reasons for giving steroids at the outset,” says Dr. Jaffe. “First, if it’s the patient’s first flare-up, you don’t necessarily know you’re going to have to treat chronically, even though many of these conditions are chronic. So, rather than commit the patient to a very long-acting implant or immunosuppressive therapy that takes several months to build up—and then you’re committing to treat him with it for years at that point—I’ll usually start with a steroid. The other reason is that steroids have a faster onset.”

The Next Level

In certain situations, usually in the setting of recurrences or in serious diseases that need to be hit hard early on, physicians will move to systemic, steroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy or possibly a long-term, sustained-release steroid implant.

“In certain presentations that are severe in the beginning and a form

|

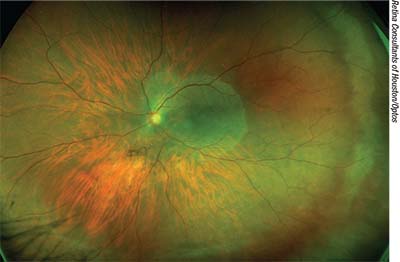

| In non-infectious uveitis, physicians usually quell anterior inflammation first before moving on to a therapy for the posterior segment. |

In addition to these serious diseases in newly diagnosed patients, patients already on therapy may show signs that they need systemic treatment. Dr. Dahr says such signs include:

• anatomic sequelae such as progressive synechiae and iris bombe;

• steroid-induced increases in IOP;

• glaucomatous optic atrophy;

• cataract;

• vitreous opacity;

• uveitic macular edema;

• retinal capillary bed dropout;

• macular fibrosis associated with inflammatory CNV;

• loss of retinal pigment epithelium with associated retinal degeneration; and

• visual field loss.

If you move to the established immunosuppressive therapy, there are several families of drugs to choose from, each with its own dosing characteristics and mechanism of action:

• Antimetabolites: azathioprine (50 mg/day orally); methotrexate (usually 2.5 to 7.5 mg/week orally, occasionally subcutaneously delivered to reduce side effects) and mycophenolate mofetil (500 to 1,000 mg/day orally);

• T-cell inhibitors: cyclosporine (50 to 100 mg/day orally) and tacrolimus (0.05 to 0.10 mg/kg/day orally); and

• Biologics: infliximab (Remicade, IV infusion) and adalimumab (Humira; 80 mg initial dose, then 40 mg a week later, followed by 40 mg biweekly via self-administered, subcutanenous injection); and

• Alkylating agents: cyclophosphomide and chlorambucil (both usually oral, though they can be given via IV).

There is also the relatively new repository corticotropin injection Acthar. Though its mechanism of action is unknown, it stimulates the body’s production of steroids. There currently isn’t any clinical trial data for Acthar’s use specifically for uveitis, though its maker, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, is conducting further investigations for the condition.

Dr. Dahr explains his approach to these immunosuppressive agents: “If I think a single drug will work in the beginning, then, in adults, I’ll usually start out with mycophenalate,” he says. “In children, I’ll often start with methotrexate. Then I’ll see how things evolve over time. If there’s the sense of a response but I think I need more of a therapeutic effect, I might add a second agent. Traditionally, this second agent was a T-cell inhibitor like cyclosporine or tacrolimus (Prograf). Lately, however, it’s been more often Humira because it gained FDA approval for uveitis. I usually don’t use Humira as my primary agent unless it’s Behçet’s disease, based on the findings of an expert panel.”1

If Dr. Jaffe feels the patient needs more than the initial steroid regimen, he chooses between an immunosuppressive medication and a long-acting drug delivery system. “If someone has unilateral or very asymmetric disease; if they can’t tolerate immune-suppressing medications; if they have a systemic condition in which immune-suppressive medications are contraindicated; or they don’t have a systemic disease for which they require either immunosuppression or a steroid, then I think the Retisert (fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant, Bausch+Lomb/Valeant) would be a good option, because it lasts about three years.

“If they have a bilateral or systemic disease like sarcoid which would benefit from an immunosuppressive medication, then I’d go to the immune-suppressing medication,” Dr. Jaffe adds.

If he goes the immune-suppressive drug route, Dr. Jaffe says he will tailor the specific agent for the patient’s disease. “For intermediate uveitis and uveitis associated with sarcoidosis, methotrexate is my first-line agent,” he says. “We’ve published a report on its efficacy in the latter category of patients.2 Methotrexate tends to have a relatively low number of side effects, is given once a week and patients tolerate it well.”

Dr. Jaffe uses the anti-metabolite mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) and azathioprine (Imuran) for conditions such as birdshot chorioretinopathy, multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. His typical dosing is 1,000-1,500 mg b.i.d. for mycophenolate mofetil and 150 to 200 mg/day for azathioprine. He may also give Humira in combination with methotrexate. “Humira is usually given in an initial dose of 80 mg and then, one week later, it’s given 40 mg/every other week.”

Drs. Jaffe and Dahr prefer to take a long-term view of uveitis treatment, especially if they’re using immunosuppressive agents. “Usually, when we make the decision to start someone on an immune-suppressing medication, I go into it with the idea that I’m going to try and treat him for at least two years, if possible, before deciding to start tapering it,” Dr. Jaffe says. “This is because there’s some evidence that if you treat someone for two years—at least in some forms of uveitis—it’ll lessen the chance that the uveitis will recur.

The other thing is, with most of these drugs—especially methotrexate—unlike corticosteroids, they don’t have a very rapid effect. It takes weeks for them to build up in the system. For example, with methotrexate, it can take between eight and 12 weeks before you reach the full, effective dosing level. And, if you increase the dose, it can take another eight to 12 weeks for it to reach the new dosing level. Therefore, it wouldn’t make sense to go into this thinking you’re going to treat someone for four to six months, because it takes most of that time just to get the patient up to full drug levels.”

If there’s no response to the therapy or the disease appears to be progressing rapidly, Dr. Jaffe notes that there are even heavier-duty agents such as the alkylating agents cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil. “These are the drugs we use when nothing else is working,” he says. “They can potentially cause serious side effects, including cancer, so we use them judiciously.”

Dr. Dahr says the recently released results of the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial help give physicians added confidence when they’re considering starting systemic therapy in uveitis patients.

In the seven-year, prospective, randomized study, uveitis patients who received systemic steroids supplemented with immunosuppression had better visual acuity (by about 7.2 letters) than those randomized to receive intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implants. “This doesn’t preclude use of the Retisert,” Dr. Dahr says. “But most of these cases are long-term patients, and you often have to think of a long-term game plan of five to 10 years. Over that longer time period, systemic therapy, per the results of the MUST study, probably gives you better outcomes.”

Possible Complications

Though many of these drugs are effective against uveitis, they do have potential side effects that could undermine your treatment efforts.

• Corticosteroids. “If we implant a Retisert and the patient is phakic in that eye, we’ll usually remove the lens and place an intraocular implant at the time of the Retisert implantation,” says Dr. Jaffe. “This is because we know the patient is going to need a cataract extraction down the road. And, the advantage of extracting the cataract when you put in an implant is that the latter keeps the eye quiet after surgery.” With intravitreal injections, surgeons warn that there’s a slight risk for complications related to the injection itself, such as intraocular infection (endophthalmitis), hemorrhage and retinal detachment.

Surgeons also note the possible complications of systemic steroid use, which include:

• increased blood pressure;

• exacerbation of diabetes;

• bone loss;

• redistribution of body fat;

• hirsutism;

• acne;

• a variety of metabolic changes;

• weight gain;

• anxiety;

• pyschosis;

• sleep disturbances; and

• tremors.3

The risk of these complications is one reason physicians prefer to have patients on 5 mg or less of a systemic steroid, and will move them onto a steroid-sparing agent if therapy will be necessary for a long period of time.

• Antimetabolites. Dr. Dahr says that, in the short term, the main issue with the antimetabolites is nausea. “They’ll often have it for the first week or two, but it will often pass,” he says. “If it doesn’t, then you have to try another member of the antimetabolite family. Some patients will experience the nausea with mycophenalate mofetil, for example, but not with azathioprine. In the long term, watch their liver enzymes, white blood cell counts and hemoglobin. This is why you should get a complete blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel every two to three months.”

• T-cell inhibitors. Dr. Dahr says that, with this family of drugs, you want to watch the patients’ liver enzymes, though there’s less risk of anemia or low white blood cell count. You also should monitor the patient’s blood pressure. “With cyclosporine, also watch for renal toxicity, low magnesium, elevated lipids and paresthesias,” Dr. Dahr adds.

• Biologics. Physicians say the primary concern when prescribing Humira is to ensure that the patient has been tested for tuberculosis, which is something the patient’s rheumatologist can usually help with.

“You have to be careful if you start a patient with intermediate uveitis on Humira because intermediate uveitis can be associated with multiple sclerosis,” warns Dr. Jaffe, “and this drug and the others in the tumor-necrosis-factor family can exacerbate pre-existing MS.”

Future Therapies

There are some uveitis treatments in the pipeline that ophthalmologists may be gaining access to in the coming year or so.

• Sirolimus (rapamycin, Santen). This is an inhibitor of mTOR, or the mammalian target of rapamycin. It brings about immunoregulation by interrupting the inflammatory cascade through the inhibition of T-cell activation, differentiation and proliferation, and promotes immune tolerance by increasing regulatory T lymphocytes. Santen filed a New Drug Application for sirolimus with the Food and Drug Administration in April of 2017.

• Durasert (fluocinolone acetonide injectable implant, pSivida). This is a long-term steroid implant designed to release drug over a period of three years. According to Durasert’s maker, pSivida, in a second Phase III trial of the insert involving 153 patients, at six months, 22 percent of Durasert patients had a recurrence of their posterior uveitis vs. 54 percent of patients in a sham group (p<0.001). However, in terms of safety, the average IOP rise in the Durasert group was 2.4 mmHg, compared to 1.3 mmHg in the sham group.

Ultimately, Dr. Dahr says ophthalmologists could treat uveitis more effectively if they stopped committing two mistakes. “A large proportion of uveitis cases won’t have any defined etiology,” he says. “Because of this, physicians will have doubts, and will undertreat or not treat at all. I say it’s better to go ahead and treat appropriately with steroid-sparing agents when necessary. The other related issue is, when you do treat, don’t just hit a patient who has severe disease with steroid injections for two years. Bite the bullet and put him on steroid-sparing therapy early on. The vast number of people take these drugs without significant complications and with tremendous benefit with regard to their eye disease. Don’t hesitate. If you have a 20-year-old with a blinding eye disease, he can go blind from VKH in 18 to 24 months and then, assuming normal life expectancy, live into his 80s. Put that kid on the medicine.” REVIEW

Dr. Jaffe is a consultant for AbbVie, and pSivida. Dr. Dahr has no financial interest in any product discussed.

1. Levy-Clarke G, Jabs DA, Read RW, et al. Expert panel recommendations for the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic agents in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:785-796.e3.

2. Dev S, McCallum RM, Jaffe GJ. Methotrexate treatment for sarcoid-associated panuveitis. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1:111.

3. Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn E, Leigh R, Brown J, Cohen A, Kim H. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:1:30.