The year was 1994 … Nelson Mandella was elected President of South Africa, the Northridge Earthquake rocked California, Tonya Harding was stripped of her skating championship for having her rival, Nancy Kerrigan, attacked; the Channel Tunnel finally opened, connecting England to France; the iconic television show “Friends” debuted; and people flocked to theaters to see “The Lion King,” “Forrest Gump,” and the “The Shawshank Redemption.” Also, in April of 1994,

|

Review of Ophthalmology premiered, under the hand of late Publisher Rick Bay, Editor-in-Chief Stan Herrin and Chief Medical Editor Mark Blecher, MD. (Review’s current EIC, Walter Bethke, joined the staff a month later as a junior editor.)

Here’s a look back at some of the developments we’ve covered over the past 25 years and how they’ve shaped ophthalmology.

Health-care Reform

One of the first ways the mainstream news of 1994 intersected with ophthalmology was First Lady Hillary Clinton’s push for health-care reform, eventually dubbed “Hillarycare” by pundits.

Among other provisions, the Health Security Act, as it was called, would require all citizens to have health care, and all employers to provide it (with financial assistance for small businesses). Cooperatives in each state would sell insurance plans to citizens and oversee insurance companies, and a National Health Board would control spending and oversee the entire operation.1,2

|

| In 1993, Review editorial board member Jeffrey Morris, MD, MPH, was on the Clintons’ health-care task force. The Clintons’ health-care bill failed to gain popularity and ultimately didn’t come to pass. “After you shave away all the mind-numbing details,” wrote Dr. Morris in a September 1996 feature on Mr. Clinton’s bid for a second term, “the underlying concept of President Clinton’s proposal was simple: Shift power away from big employers and insurance companies and give it to patients and physician networks.” |

Organized ophthalmology took issue with one provision of the plan that proposed establishment of cataract “Centers of Excellence”—surgical centers in urban areas that would be able to perform cataract surgery, coronary artery bypasses and other procedures for less cost to Medicare. The American Society of Cataract and Refractive surgery opposed this provision. A news article from Review’s second issue stated ASCRS’s opposition to the Centers on the following grounds: “ ‘Centers of Excellence’ implies that providers sanctioned by the government would offer a higher quality of care than other physicians in the same area; Medicare would also pay beneficiaries to seek care at these centers; the provision is an unnecessary and unfair government intrusion into the marketplace, because smaller providers will not be able to compete with the Centers; by focusing only on the competition the Centers will foster, supporters are focusing only on cost and not on the issues of quality and access.” Ultimately, much to the chagrin of Mrs. Clinton and her task force, but maybe to the relief of ASCRS members, the bill was nixed in the fall of 1994.

A lot of ink was also devoted to the specter of managed care, which, to hear some observers tell it, appeared to be growing like a deadly virus in a host body. Articles with titles such as, “Will Your Patients Go to a Medicare HMO?”, “Yes You Can Profit from Managed Care Plans,” “How I Succeed in a Managed Care World,” and “Why I Joined Forces with the Enemy,” filled each issue.

In our premiere issue, cataract and refractive pioneer Richard Lindstrom, MD, dispensed tips on existing in the brave new world of managed care. Among them were “lower your standard of living,” diversify your income stream by offering refractive surgery, invest in real estate and businesses other than your own; and lobby your state legislature. “Adapting to managed care isn’t easy. It’s hard,” Dr. Lindstrom wrote. “However, practicing under managed care can still be rewarding, as long as you are proactive. Fortune will favor you if you’re prepared, and 80 percent of success is being in the right place at the right time. Make sure you do both and you’ll do fine under managed care.” Soothsayers who saw the writing on the wall and positioned themselves to succeed in managed care were ultimately proven right: Today, more than 80 percent of covered individuals are in a managed-care plan, according to the latest data from Managed Care Online.3

Refractive/Cataract Rewind

In the mid-90s, phaco was providing the buzz in cataract surgery, with the magazine featuring many discussions on innovative ways to break up the nucleus.

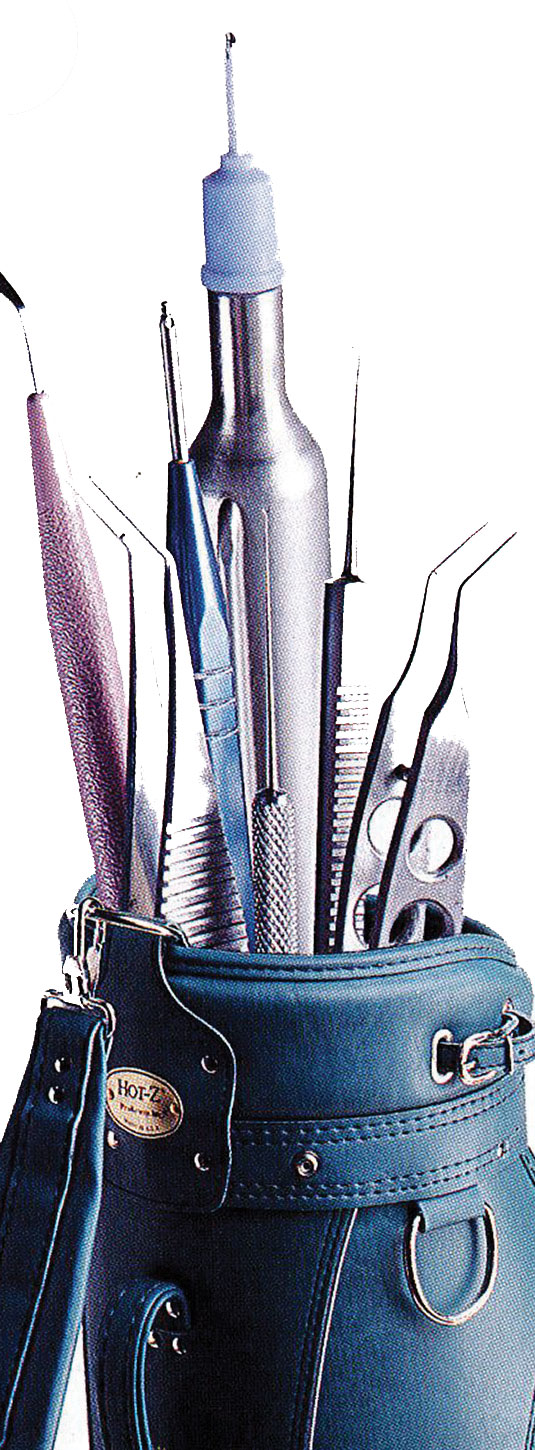

Two surgeons offered creative takes on cataract surgery in our June 1994 issue. First, Danville, Illinois, surgeon Dave Dillman likened his approach to cataract surgery to a golfer who “uses all 14 clubs.” “I’ll wager you’ll never see a professional golfer in a tournament play the course with only four clubs in his or her bag…” he wrote. “I like to think of cataract surgeons as ‘professionals’ as well, and yet, I wonder how many of our ‘pros’ walk into the operating room with only four clubs in their bag? My guess is way too many. So, let’s discuss how we can identify and use the variables, the ‘clubs, [the balance of fluid ingress and egress, aspiration flow rate and followability, the right phaco needle for the right situation and others] that are available to us during phacoemulsification.”

In the same issue, Boca Raton, Florida, surgeon Alan Aker advocated a unique approach that drew on Eastern philosophies to allow cataract surgeons an almost Zen-like mastery over their procedures. Though the article is old, the advice remains fresh. Drawing on the work of psychologist Albert Bandura, Dr. Aker wrote that the people most successful in life don’t just have raw talent, but possess several other qualities: persistence, even in the face of difficulties and setbacks (such as a torn capsule); an understanding of, and belief in, their own capabilities in order to motivate them; and they all have a philosophy of constant self-improvement. “They methodically analyzed their setbacks and learned from their mistakes,” Dr. Aker wrote.

In addition to beginning to embrace topical anesthesia and clear corneal incisions for more of their cases, following are some other steps in cataract surgery’s evolution that Review covered over the years:

• Phaco technology. Though phaco had been around since the late 1960s thanks to Charles Kelman, MD, the 1990s and early 2000s saw a flurry of innovations both in techniques and technology that kept surgeons constantly exchanging new thoughts on the subject. There seemed to be a new phaco machine almost every year.

|

| Dave Dillman, MD’s, phaco golf bag. |

One of the main problems both manufacturers and surgeons alike constantly contended with was occlusion breaks and post-occlusion surges. In response came inventions such as dual-linear-control footpedals and phaco burst on Bausch + Lomb’s machines, NeoSonix on the Alcon Legacy, “sonic phaco” on the Staar Wave device and WhiteStar phaco on the (then) AMO Sovereign. These incremental changes led to the features on the Alcon Centurion, the B + L Stellaris Elite and the WhiteStar Signature Pro from Johnson and Johnson Vision that surgeons use today.

Around this time, micro-incision, or “bimanual,” phaco also grabbed some surgeons’ interest. But, as Cincinnati’s Robert Osher, MD, said in an article from that period, more pieces of the puzzle needed to be in place for micro-phaco to take off: “When we have a superior lens to fit through a 1.2- to 1.5-mm incision,” Dr. Osher said, “then micro-phaco will become the standard of care.”

• Tackling spherical aberration. Also in the early 2000s, lens researchers began to think there was more to postop cataract surgery vision than just acuity, and that spherical aberration may have a hand in the quality of patients’ vision. This led to the eventual trial and approval of the AMO Tecnis IOL (now made by Johnson & Johnson Vision), which was designed to counteract the positive spherical aberration present in the cornea. Approvals of the B+L SofPort AO and the Alcon AcrySof IQ followed. Though they each took different approaches to handling a patient’s SA, many surgeons saw value in the idea. “The need to manipulate spherical aberration derives from the improved clarity of vision (or contrast) under mesopic and photopic conditions,” wrote Ontario’s George H.H. Beiko, BM, BCh, FRCSC, in a Review article on the topic in 2008, “as well as the improved functional performance under night driving conditions.”

|

• Premium IOLs. In the United States, cataract surgery in general, and premium intraocular lenses in particular, took a major step forward in November of 1998 when the first toric intraocular lens, the Staar Toric IOL, was approved. As Sarasota, Florida, surgeon and Staar investigator Harry Grabow commented in Review’s December 1998 issue, “Few surgeons actually do AK at the time of surgery,” he said, noting that many surgeons would feel more comfortable with the idea of correcting astigmatism with a lens. “The correction for astigmatism is a fixed and known value in the implant, so we’re not dependent on corneal healing, age or the depth of our incisions as variables,” Dr. Grabow added. “The only variable is the final position of the IOL.”

The Staar Toric proved to be the tip of the iceberg, with many toric lenses and presbyopic-correcting IOLs from the other major manufacturers following it in the years to come. The first multifocals approved were AMO’s ReZoom and Alcon’s ReSTOR, soon followed by the Tecnis MF and the Crystalens from B+L, leading up to today’s most recently approved technologies: the Tecnis Symfony and the Alcon PanOptix trifocal.

An innovative technology that Review has followed closely since 2002 is the adjustable IOL from RxSight, formerly called the Calhoun Lens. The lens’s power can be manipulated after implantation via a special light-delivery device until the patient’s happy with the result. “It’s FDA-approved and seeing a slow commercial release in the United States,” notes Review’s cataract and refractive editor Arturo Chayet, MD, who took part in the lens’s clinical studies.

• Femtosecond cataract. This technology made a big splash when it appeared, especially with its ability to create circular capsulorhexes. Some surgeons rushed to adapt their techniques to use it, while others adopted a wait-and-see attitude, stating that they’d like to see more definitive femtosecond-cataract results in the literature that would tip them over to the FLACS camp. In our March 2015 issue, a surgeon who took part in a Veterans Administration meta-analysis of peer-reviewed literature on FLACS to help determine whether the VA would implement it chimed in. “In terms of other complications, femtosecond and conventional surgery had the same adverse events and the rates of complications were comparable between the two,” said Ken Gleitsmann, MD, an ophthalmologist from Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, one of the report’s co-authors. “However, a lot of this has to do with the small size of the study groups. As femtosecond goes out into the marketplace and you have a million cases to look at, things may look a little different. Also, making things more difficult is the fact that the complication rates with conventional surgery are so low; to get something even lower than that is difficult.”

Though surgeons say both manual cataract surgery/phaco and FLACS produce very good outcomes, the latter may be the go-to in challenging cases with pseudoexfoliation and brunescent lenses. Despite this, many surgeons remain on the fence.

|

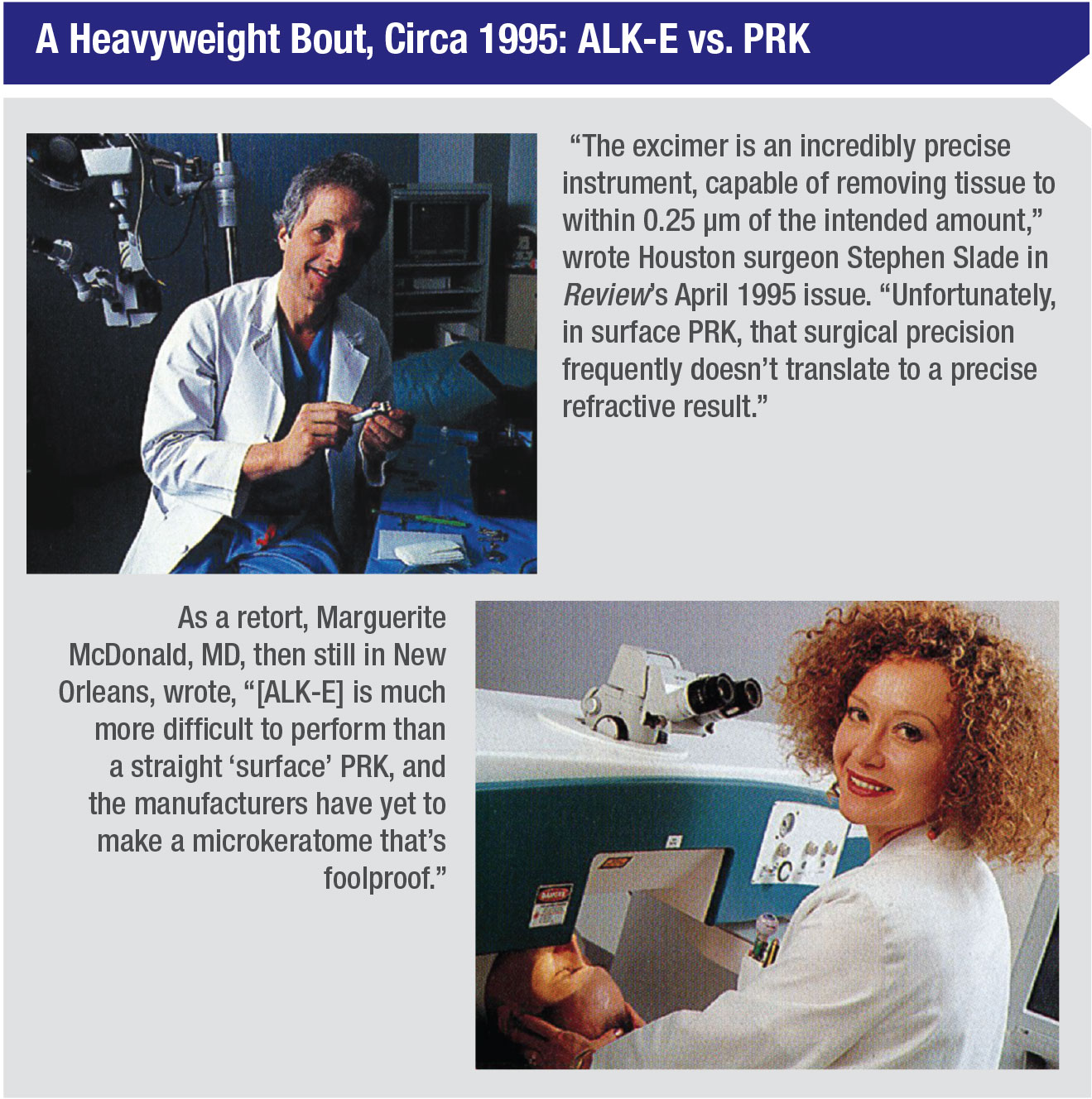

• Excimer-based refractive surgery. In October of 1995, the Summit excimer laser fired the pulse heard ‘round the world and became the first laser approved for photorefractive keratectomy in the United States. “The concept of using a high-tech laser to ‘sculpt’ corneal tissue has captured the imagination of doctors, financial investors, journalists and the public like no other procedure or device in ophthalmic history,” wrote Jack Persico, then Review’s special projects editor in a feature about the potential of the new procedure. Three years later, LASIK would be approved, touching off debates over which procedure was better, such as the “Point-Counterpoint” in our April 1995 issue, written before LASIK was officially approved, when it was known as laser ALK or ALK-E (excerpts from it appear to the left).

Though LASIK would go on to become the dominant refractive surgery procedure in the country, the emergence of ectasia in some cases eventually let PRK up off the mat and back into the refractive surgeon’s armamentarium as a trusty alternative for certain patients. Relatively recently, small-incision lenticular extraction, or SMILE, has arrived, vying for a seat at the table, with some surgeons arguing it has advantages over LASIK.

A Revolution in Retina

Carl Regillo, MD, the director of Wills Eye Hospital’s retina service, and co-editor of Review’s Retinal Insider department, recalls what it was like treating wet age-related macular degeneration patients in 1994. “We would examine most of them once and say, ‘Sorry. We can’t do anything for you,’ ” Dr. Regillo says. “It was a hard conversation to have, telling these patients they would be experiencing severe vision loss in another 12 to 18 months.” The best he could do was refer them to a low-vision specialist, knowing that even the most sophisticated magnifying devices wouldn’t stop 90 percent of them from going blind.

Since then, retinal care has undergone a sea change, resulting in greatly improved outcomes and continually increasing patient and clinician expectations. Advances in injectable anti-VEGF therapy, continuing to this day, have enabled Dr. Regillo and his colleagues to save and actually improve the vision of thousands of patients once doomed to live out their lives without vision. Miniaturization of surgical instruments, refined surgical techniques and improved diagnostic equipment have combined with the new therapy to put retinal practice at the forefront of modern eye care.

“Retina has undergone a virtual revolution in just about every aspect of our practices in the past 20 to 25 years,” says Dr. Regillo. “It’s nothing short of amazing.”

“[PDT] was the first significant step forward in achieving better outcomes for wet AMD patients,” he reflects. “All of a sudden, AMD became a routine manageable condition.” As the early years of the 21st century unfolded, ongoing progress soon included the treatment of diabetic retinopathy and retinal vein occlusion with intraocular injections of steroids.

Meanwhile, in advance of the historic debut of anti-VEGF therapy, the first optical coherence tomographers made their way into retina specialists’ offices, and eventually helped establish a new standard of care. “OCT was a landmark advance in diagnostics,” Dr. Regillo says. “It arrived at the perfect time for us, when anti-VEGF therapy was coming into our hands.”

|

After Macugen had its brief moment in the sun, Dr. Regillo says 2006 was another milestone year, introducing a second wave of anti-VEGF therapies. “We saw a major leap forward for wet AMD,” he recalls. “Lucentis replaced Macugen that year, and soon Avastin (bevacizumab) and Lucentis (ranibizumab) powered our therapeutic practices like never before.”

In 2011, Eylea (aflibercept) was released and approved to provide effective treatment for diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, wet AMD and macular edema following retinal vein occlusion. “Now we could confidently treat wet AMD, DME, and RVO—the three most common medical retinal conditions,” he says. “Eylea, Avastin, and Lucentis emerged as the so-called pan-VEGF-A blockers.”

Besides the landmark emergence of anti-VEGF therapy, Dr. Regillo says the ability to view surgery on a 3D screen rather than through the microscope, as well as small-incision, trocar-based surgery and widefield viewing have each made an impact.

“Of all the advances on the surgical side, obviously, the introduction of small incision, trocar-based vitrectomy surgery has been very significant,” he says. “But couple that with modern widefield viewing, and I think you can say today’s surgery is revolutionary. Widefield viewing is probably one of the biggest advances in allowing us to be much more capable, because, as surgeons always say, ‘You can’t treat what you can’t see.’ ”

Reflections on Glaucoma

Peter Netland, MD, PhD, professor and chair, University of Virginia School of Medicine, and Review’s Glaucoma Management co-editor, reflects on the changes physicians have witnessed since the 1990s.

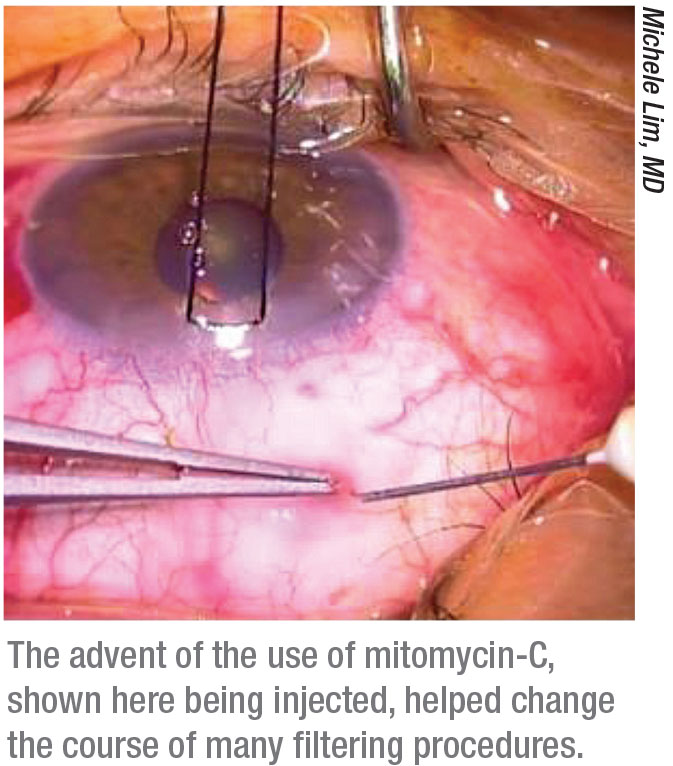

“In glaucoma, we monitored patients with disc photos (not OCT),” he recalls. “We had timolol for primary medical therapy along with drugs such as pilocarpine, epinephrine and dipivefrin (Propine). We treated patients with trabeculectomy, had started using antifibrosis drugs (5-fluorouracil), and were gaining experience with glaucoma drainage implants. Use of drainage implants was accompanied by serious complications, and we continued to perform an occasional full-thickness filter in order to achieve low postop IOP. ”

Dr. Netland says the subspecialty has come a long way since then. In terms of monitoring the disease, OCT has become useful for glaucoma specialists. In fact, physicians are pushing it further than was once thought possible. “Once you broaden your scanning to include the macular region,” wrote Senior

Editor Christopher Kent in our August issue’s Technology Update, “OCT may be very useful, even in advanced disease.”

|

Another major change in the treatment of glaucoma came with the approval of Xalatan (latanoprost; launched by Pharmacia & Upjohn) in 1996, followed by subsequent approvals of other prostaglandin analogs, and their promise of q.d. dosing. In a piece in the July 1996 edition of Review, glaucoma specialists Eve Higginbotham, Carl Camras, Dale Heuer, Alan Robin and Thom Zimmerman expressed their excitement over Xalatan. “For the first time in two decades, ophthalmologists have what we believe to be a truly new ‘first-line’ glaucoma drug …” they wrote. “Because our experience with this drug was so positive during the investigation, we believe clinicians may consider latanoprost as a first-line therapy for glaucoma, particularly for patients who have a cardiopulmonary contraindication to beta-blockers, as well as normal-pressure glaucoma patients.”

|

Dr. Netland notes that, fortunately, there is now an array of new medications, including generic latanoprost, Vyzulta (latanoprostene bunod, Bausch + Lomb), Rhopressa (netarsudil, Aerie), Rocklatan (netarsudil + latanoprost, Aerie) and Xelpros (latanoprost without BAK preservative, Sun Pharma).

Looking back over the past quarter- century, Dr. Netland closes with some very kind words. “Review of Ophthalmology has informed and updated us, provided important new information and given perspectives that have strengthened our clinical practice and helped ‘move the needle” forward,’ ” he says. “I have personally enjoyed working with the outstanding professionals at Review for all of its history. Congratulations on reaching a milestone anniversary, and sincere best wishes for the future.” REVIEW

1. Jansson, B. The Reluctant Welfare State: American Social Welfare Policies. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 2001: 366-367.

2. Moffit R. A guide to the Clinton health plan. The Heritage Foundation (online report) Nov. 19, 1993. Accessed 23 September 2019.

3. Current National Managed Care Enrollment, 2016. Managed Care Online. http://www.mcol.com/current_enrollment. Accessed 17 September 2019.