Researchers in New York City believe they may have found the link tying together age-related macular degeneration—today’s leading cause of blindness—and cardiovascular disease—today’s leading cause of death. The MDs behind this development explain that the link has been elusive because both AMD and CVD are “umbrella” categories, and the link only becomes apparent when looking at the right subgroups.

“There are two fundamental forms of early macular degeneration, and they’re very different,” notes R. Theodore Smith, MD, PhD, a professor of ophthalmology and neuroscience at the Icahn School of medicine at Mt. Sinai in New York City, and the director of biomedical imaging at the NY Eye and Ear Infirmary. (His partner in developing this theory is K. Bailey Freund, MD, a clinical professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.) “One causes drusen; the other causes what are called subretinal drusenoid deposits,” Dr. Smith says. “Both can progress to ‘wet’ macular degeneration, but the drusen are the result of a local process, not hardening of the arteries. Only the subretinal drusenoid deposits are triggered by poor vascular perfusion.”

|

|

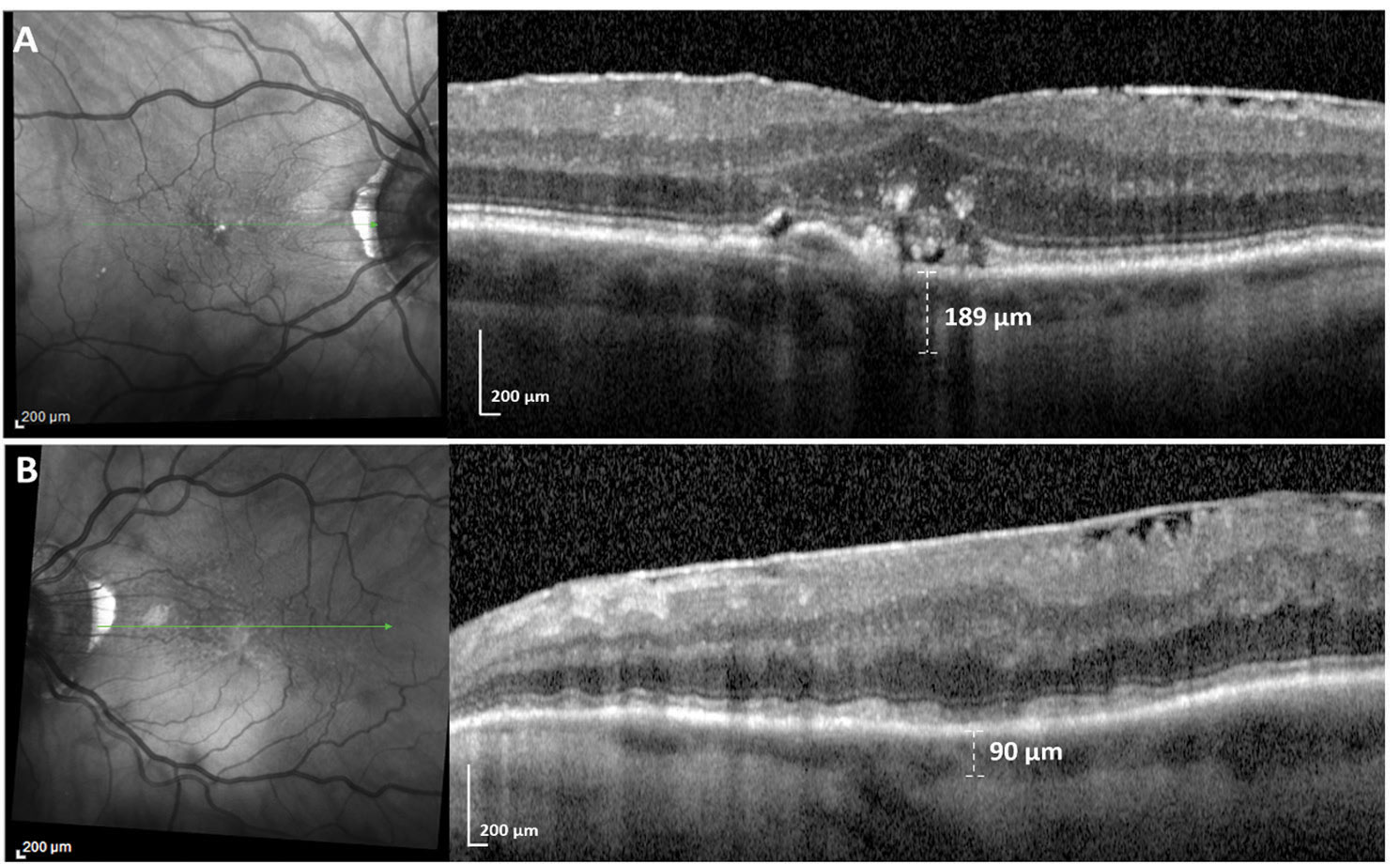

A patient who has had a stroke on the left side. The top scans show the unaffected right eye; the visible lumps are soft drusen, lying underneath the RPE. The left retina (bottom scans) is packed with subretinal deposits on top of the RPE, caused by poor perfusion following the stroke. On the right, they create a wavy appearance in the layer above. The en face scan on the left has small, dark dots widely spread, with more toward the top of the image; those are the subretinal deposits. Note that the choroid layer has shrunk from 189 µm in the right eye to 90 µm in the left eye, a consequence of insufficient blood flow. |

Dr. Smith notes that surgeons can miss the subretinal deposits on OCT because they tend to be more peripheral, out toward the arcades, especially superiorly. “That’s because of gravity,” he says. “When blood flow becomes insufficient, the superior vessels lose flow first; over time, the deposits appear lower and lower. In contrast, drusen, driven by local factors, tend to start in the central retina. The location difference may also relate to rods and cones; drusen tend to appear among cones, which are largely in the middle of the eye; subretinal deposits tend to appear amidst rods, which are more peripheral.”

So what’s the clinical value of catching these in a scan? “In terms of caring for the eyes, you wouldn’t do anything differently than if you found drusen,” says Dr. Smith. “If there’s no neovascularization, you follow the patient and see what happens. However, those deposits won’t form unless there’s inadequate blood flow to the retina, which almost certainly means there’s inadequate flow systemically. So, if I find those subretinal deposits, I send the patient to a cardiologist or neurologist. This patient may be in serious danger of having a stroke or heart attack.”

Dr. Smith says surgeons don’t usually look at the superior part of the scan. “They’re looking at the central macula for the fluid buildup from choroidal neovascularization,” he says. “The first place I look when I’m reviewing an OCT scan of a macular degeneration patient is the superior macula. If the deposits are up there, I’ll spot them. If I don’t find them there, I probably won’t find them anywhere else.”

Dr. Smith points out that the other way to find subretinal deposits is to look at the en face image of the retina on the left-hand side of the OCT scan. “On those scans drusen look like bright or reflective spots. There will be more in the middle, and they’re different sizes. The subretinal deposits are a bunch of little dark dots, all the same size, and spread around uniformly. People tend to ignore them because they don’t know what they are. They may also escape notice because the left-hand image often shows 30 green scan lines at once, making it a challenge to evaluate the underlying image. But with one click you can turn off the grid pattern and just see the picture. Then it’s much easier to spot those little dark dots.”

RRD Repair: Is Slow and Steady Best?

|

|

An en face OCT image of a patient’s retinal folds. |

Single-operation success has long been held as a marker for surgical success, but a new post hoc analysis of the PIVOT trial data presented at the Retina Society and ASRS this year suggests that even though pneumatic retinopexy has a lower single-operation reattachment rate than pars plana vitrectomy, it seems to induce fewer anatomic abnormalities that affect long-term visual acuity.

“We’ve been learning over the last few years that it’s not just about how often but how well you reattach the retina,” says Rajeev Muni, MD, FRCSC, an assistant professor in the department of ophthalmology and vision sciences at the University of Toronto.

One of these abnormalities is outer retinal folds, which are partial-thickness folds of the photoreceptor layer. “Instead of the photoreceptor layer being in contact with the RPE, it’s folded in such a way that the photoreceptors are in contact with each other,” Dr. Muni says. He and his group assessed the incidence of postoperative ORFs in PPV and PnR following rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.1

“We assessed the macula-off patients from the PIVOT trial and found that there were differences in their functional outcomes based on whether they had folds or not,” says Wei Wei Lee, MD, a retina fellow at the University of Toronto. “In the PnR group, the risk of ORFs was 14.3 percent, and in the PPV group, the risk was significantly higher at 34.1 percent (p=0.011).”

Dr. Lee says all folds resolved before six months, except in one PPV case which took eight months. “When we compared all PnR and PPV patients who had folds at one month and those who didn’t, there was a 9.4-letter difference in

ETDRS visual acuity—almost two lines of vision, with vision being worse in patients with early ORFs. Mean ETDRS acuity was 65.7 in patients who had ORFs at one month and 75.1 in patients who didn’t have ORFs at one month.”

Dr. Muni says there’s a possibility that something else about PnR or PPV is causing these differences in vision. “Perhaps ORFs are correlative but not causative,” he says. To learn more, the team performed a subgroup analysis of the PPV patients. “There was a 12.6-letter difference between those who had outer retinal folds (62.8 letters) and those who didn’t (75.4 letters). This was powerful data. It tells us that this anatomic outcome that we can detect on imaging has a significant impact on long-term visual acuity. We also found that the closer the folds were to the fovea, the stronger the correlation with vertical metamorphopsia.

“Even though the PPV single-operation reattachment rate is greater by 12 percent, is it worth it if patients have these microstructural or other anatomical abnormalities and have worse vision?” adds Dr. Muni, who prefers first-line PnR. “A patient’s final vision matters most to me.”

He proposes a modified vitrectomy approach to avoid ORFs, called minimal-gas vitrectomy. “We perform a full vitrectomy but then put just a small gas bubble in and leave the retina to reattach itself naturally by the RPE pump,” he says. “A detached retina causes little corrugations. In another study we recently published, we found the retina reattaches in five specific stages.2 We learned that the corrugations resolve in stage two, before the retina comes in contact with the RPE, which is stage three. By draining fluid in vitrectomy, you’re basically rushing through stage two so fast the corrugations don’t have time to resolve.”

If you’ve never seen these folds before, you’re not alone. It’s not easy to see ORFs, mostly because catching them requires tediously scrolling through every cut of your en face OCT volume scan. “If you just look quickly at a five-line raster scan, you won’t pick these up,” Dr. Muni says. (His group developed a custom segmentation algorithm with high sensitivity for detecting ORFs, making visualization much easier.) Ultimately, he says retina surgeons should be comfortable performing all techniques of RD repair so they can choose the most appropriate procedure for an individual patient.

1. Lee W, Bansal A, Sadda S, et al. Outer retinal folds following pars plana vitrectomy vs. pneumatic retinopexy for retinal detachment repair: Post hoc analysis from PIVOT. Ophthalmol Retina 2021. In Press. [Epub September 11, 2021].

2. Bansal A, Lee W, Felfeli T, Muni R. Real-time in vivo assessment of retinal reattachment in humans using swept-source optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol 2021;227:265-274.

Slow Taper of Steroids Effective in Postop Iritis

Idiopathic persistent iritis after cataract surgery is a distinct clinical anterior uveitis most common in African-American and female patients. It’s characterized by an unexpected onset of iritis after cataract surgery and a high rate of steroid dependency, glaucoma and macular edema. Recent research suggests it’s best treated with an initial slow taper of topical steroids, although adjuvant systemic anti-inflammatory therapy may be necessary for remission and complication avoidance.1

This retrospective interventional case series included 45 patients with idiopathic persistent iritis after cataract surgery patients (86.7 percent African American, 77.3 percent female) who were evaluated for demographics, clinical characteristics and immune blood markers. Those with more than six months of follow-up were evaluated for treatment efficacy in achieving remission (absence of inflammation for three months), with either exclusive slow tapering of topical steroids or systemic immunosuppression.

Antinuclear antibodies were present in 69.9 percent of patients. The main complications were steroid dependency (84.4 percent), glaucoma (53.5 percent) and macular edema (37.5 percent). The proposed treatment strategy achieved remission in 93.8 percent of the population, with a mean of 6.1 months via tapering of topical steroids in 46.9 percent of patients. However, in 53.1 percent of cases, adjuvant anti-inflammatory systemic medication was indicated. Meloxicam use was associated with remission in 64.7 percent of these patients; in the minority with persistent iritis, treatment was escalated to methotrexate, which was successful in all of the cases.

The authors recommend “a strict systematic treatment with an algorithm which begins with a slow tapering of steroids over two months and, if iritis flares, systemic medication should be introduced, escalating from meloxicam to methotrexate.”

1. Soifer M, Mousa HM, Jammal AA, et al. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic persistent iritis after cataract surgery (IPICS). Am J Ophthalmol. October 12, 2021. [Epub ahead of print].