Kevin J. Corcoran, COE, CPC

For most refractive surgery patients, their procedures are a way to get out of glasses to improve their appearance, or to take a dip in the ocean without the hassle of contact lenses. For others though, refractive surgery is a way to improve vision that's been damaged due to trauma or surgery. However, there are currently no universal, well-accepted guidelines to differentiate between cosmetic and therapeutic refractive procedures that might help a physician get reimbursed by third-party carriers.

In this article, we'll describe the general guidelines we use to differentiate between cosmetic and therapeutic refractive surgeries in our practice, and how we code the therapeutic procedures in an effort to receive some reimbursement for them. Though insurance companies don't always recognize these procedures as reimbursable, we hope that a discussion of our definitions will get other surgeons, and third-party payers, thinking about practical payment guidelines for such surgeries.

Walking a Fine (Guide)line

When attempting to differentiate cosmetic from therapeutic refractive surgery, we have an obligation not to draw guidelines that are too broad

and overutilize the health insurance system. Spending the insurance companies' resources on refractive surgery could hamper their ability to cover the expenses of other medically necessary services. Certainly, no one wants to trade coverage of a procedure such as an emergency iridotomy in an angle-closure attack for corneal refractive surgery. On the other hand, a patient with severe astigmatism or anisometropia following a corneal transplant who is unable to tolerate contact lenses shouldn't be forced to pay for a medically necessary surgical correction out of pocket if our health insurance system is working properly. By the same token, health insurance companies need to apply a prudent and fair policy toward therapeutic refractive procedures, and not take advantage of confusion in the marketplace to avoid paying for medically indicated services. Our job as eyecare providers is not only to provide treatment to our patients, but also to act as advocates for them when it comes to receiving appropriate insurance coverage.

|

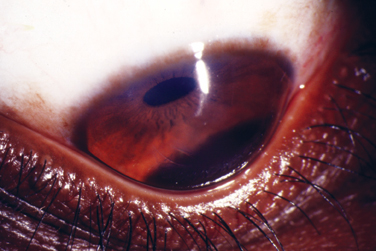

| A therapeutic refractive procedure may be able to help a keratoconus patient recover some useful vision and tolerate contact lenses. |

• Lessons from cataract surgery. In formulating a set of coverage guidelines, ophthalmologists should consider accepted criteria from other areas of ophthalmology and medicine in general. The payment guidelines for cataract surgery provide a useful reference.1

Most insurance carriers will cover cataract surgery when the patient's best corrected visual acuity falls to the 20/50 level, or 20/40 with complaints of glare, and when the patient's cataract interferes with the activities of daily living, such as reading or driving. In the cataract arena, visual function as measured by visual acuity in both bright and dim illumination is widely accepted. Glare testing is applicable when the patient's subjective complaints exceed measured visual acuity. Contrast sensitivity testing is not widely used, but some recommend it to evaluate the symptoms of those patients who might have contrast sensitivity problems related to the cataract when a black-and-white visual acuity chart in well-controlled room lighting doesn't fully reflect their visual disability. In these situations, we've learned to depend mostly upon our clinical judgment and experience in drawing the line between cataract surgery that insurance should pay for and refractive lens exchange or clear lens extraction that requires the patient to pay.

| Table 1. Therapeutic Procedures and Their Billing Codes | |||

| Therapeutic Name | Similar Refractive Procedure | Therapeutic Indications | Codes Used |

| therapeutic lamellar keratomileusis | laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) | Management of pathologically high levels of irregular astigmatism or anisometropia. | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 996.51, 367.22, V42.5, V45.6, 367.31 Fee: Billed to insurance |

| therapeutic conductive keratoplasty | conductive keratoplasty (CK) | Management of pathology causing irregular astigmatism associated with keratoconus or high levels of induced irregular astigmatism or anisometropia from corneal transplantation or following cataract surgery.18 | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 996.51, 367.22, V42.5, V45.6, 367.31, 371.6 Fee: Billed to insurance |

| phototherapeutic keratectomy | photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) | Manage pathologic situations such as recurrent erosion or high levels or irregular astigmatism or anisometropia following other surgical procedures.19-23 | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 371.42, 371.52, 371.03, 996.51, 367.22, V42.5, V45.6, 367.31 Fee: Billed to insurance |

| therapeutic Intacs | Intacs | Manage patients with corneal ectasia and irregular astigmatism for situations like keratoconus or ectasia following other surgical procedures. | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 371.60, 367.22, 367.31 Fee: Billed to insurance |

Similarly, in the field of intraocular lenses, IOL exchange for postoperative refractive surprises has become accepted in the ophthalmic community when the patient's degree of anisometropia reaches the level of 2 to

3 D, and is associated with intolerance to spectacles, particularly in the elderly for whom contact lenses may not be a useful option.2,3

• Keratoconus guidelines. In a vein similar to cataract, there are coverage guidelines that define when a patient with keratoconus has enough disability to warrant contact lens coverage or needs to undergo corneal transplantation. In a keratoconus patient, when eyeglasses are no longer sufficient to correct vision due to decreased visual acuity, anisometropia or glare, contact lenses are considered medically indicated and are reimbursable by many insurance companies. Later, when the patient becomes intolerant to contacts and glasses, or if scarring interferes with reading or driving with correction in place or prevents adequate vision (20/30 or below with or without glare), corneal transplant surgery is medically indicated.

With these situations in mind, therapeutic refractive surgery should be considered medically necessary for the correction of post-surgical or pathology-induced anisometropia in which the patient can't tolerate spectacles and contact lenses. The spectacle correction of anisometropia over

2 D in any meridian necessitates lenses of significantly unequal power, which induces a prismatic imbalance that interferes with reading, especially when the imbalance is vertical. Even a small amount of aniseikonia can disrupt binocular vision in adults and can lead to troublesome symptoms such as diplopia, reading difficulties, headaches, vertigo and poor depth perception.4,5 While contact lenses can minimize symptoms of aniseikonia in some patients, not everyone can tolerate them, and they're contraindicated in some ocular or systemic conditions. When contacts aren't an option, it's our opinion that therapeutic refractive surgical procedures then become medically indicated. Surgical options for treating anisometropia are the same as those used for correcting other forms of refractive errors.

• Therapeutic procedures. We feel that an appropriate naming system should be in place to enable clear communication between the physician, patient and payer. To that end, we've used the word "therapeutic" in our practice to label those procedures that we feel are medically indicated and aren't provided solely for the purpose of reducing dependence on glasses or contact lenses.

For instance, therapeutic lamellar keratomileusis (TLK) is a LASIK procedure that is used in the management of high levels of irregular astigmatism or anisometropia.6-9 At our practice, we also perform therapeutic conductive keratoplasty and therapeutic Intacs procedures in certain patients. We base our use of these procedures on published studies in the case of Intacs4,5,10-16 and our own in-house results of CK with almost two years of follow-up.17 Table 1 contains a summary of the terminology and therapeutic indications that we use in our practice to distinguish these procedures from their cosmetic counterparts.

In addition to corneal procedures, in certain cases of anisometropia in which a patient still has useful accommodation following trauma in the opposite eye, a phakic IOL implant procedure may be medically indicated and would be termed therapeutic phakic IOL implantation. Similarly, in patients without useful accommodation or with nuclear sclerosis who suffer from anisometropia following trauma in the opposite eye, clear lens extraction/IOL implantation may be medically indicated and would be termed therapeutic refractive lens exchange.

In general, we feel the physician should use the procedure that best fits the patient's refractive error, yet specific clinical factors may direct him toward another, more appropriate one. There are also times when a surgeon needs a combination of procedures to obtain the desired outcome, where one procedure might be done for a medically indicated reason and billed to the insurance company, and the other is cosmetic and billed to the patient.

Cost Analysis

Therapeutic refractive procedures tend to be more complicated. They usually involve higher levels of decision making, patient counseling, postoperative care and possible complications that usually need additional intervention for their management. Because of this increased complexity, our professional fee for these cases is about 30 percent higher than the charge for patients with more straightforward refractive errors or who don't start out with irregular astigmatism.

We also have significant operating costs involved in the procedure that aren't usually reimbursed separately, including the cost of:

• access to the excimer laser;

• the microkeratome; and

• the equipment used during the procedure, which typically includes, at least, a metal keratome blade, medications, supplies and contact lenses.

We currently charge a global fee for therapeutic procedures, which includes the surgical procedure and the postoperative care for 90 days. We bill the examination that determines the need for surgery separately. We also bill for postop care after the initial 90-day period. If the patient needs to return to the operating room during the first three months for management of a complication, we bill these procedures using modifier -78.

|

| Intacs can help manage patients with corneal ectasia or irregular astigmatism. |

If the surgeon plans on staging the surgical intervention, such as in a case where he performs relaxing incisions first and then plans to perform a PTK a month later, the second procedure is billed with modifier -58. If additional surgical intervention is required after the 90-day global period, then the procedure is billed in a manner similar to any initial procedure. Situations that require an extraordinary amount of work are identified with modifier -22.

Examples of Therapeutic Corrections

To help you get an idea of how these guidelines might work in practice, here are some possible scenarios:

• Case #1: A 48-year-old male comes in with a history of traumatic recurrent erosions in his right eye. His ophthalmologist finds anterior basement membrane dystrophy both eyes, yet the patient is symptomatic only in the right eye from the recurrent erosions. His refractive error is -4.5 D in both eyes. The patient has failed treatment with lubricating drops and ointments.

After discussing their options, the patient and the surgeon feel it's in the patient's best interest to proceed with phototherapeutic keratectomy to increase adhesion of the epithelial cells to Bowman's layer and reduce the frequency of recurrent erosions. This therapy is effective in 90 percent of patients.20 The patient prefers to leave his refractive error as it is, and desires treatment of the recurrent erosions only.

This patient would then undergo a PTK, which entails removing the epithelium, scraping off any residual anterior basement membrane material, and then applying between 4 and 8 µm of treatment to all areas of the exposed cornea. This medically necessary procedure would be reported as an unlisted procedure code (66999). This is the best choice to report these surgical procedures, because no other CPT code makes sense. The medical indications that justify this procedure are identified on the claim using ICD-9 codes describing recurrent erosion of the cornea (371.42) and anterior corneal dystrophy (371.52).

| Table 2. Charges for Complex Refractive Procedures | |||

| Case # | Name of Procedure | Indications | Codes Used |

| 1 | photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) | Refractivecorrection with PTK to the periphery to prevent erosions | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 367.10, 371.42 Fee: Refractive, not billed to insurance |

| 2 | complex-case Intacs & conductive keratoplasty (Intacs and CK) | Reduce refractive error in patients with keratoconus | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 367.10, 371.60, 367.22 Fee: Refractive, not billed to insurance; complex-case fee |

| 3 | complex-case LASIK | Reduce refractive error in patients with corneal transplants | Surgical: 66999 Diagnosis: 367.10, 367.21, V42.5, 367.22, 371.60 Fee: Refractive, not billed to insurance; complex case fee |

• Case #2: A patient with keratoconus is now contact lens intolerant and is having trouble with her reading and driving. Her best-corrected vision is 20/30, but she still has significant levels of glare and distortion of her vision and is symptomatic from the keratoconus. Non-surgical measures haven't been able to relieve the condition.

In our experience, therapeutic conductive keratoplasty and/or therapeutic Intacs would be useful to rehabilitate this eye's vision. Again, an unlisted procedure code (66999) is the best choice to report these surgical procedures, because no other CPT code readily applies. One of the ICD-9 codes in the range 371.6x (keratoconus) would support the claim for this procedure.

• Case #3: A patient with a corneal transplant has high levels of irregular astigmatism and anisometropia and is left with poor vision in spectacles and is contact lens intolerant. Despite corneal guttata, the pachymetry and specular microscopy show adequate corneal thickness, wound alignment and endothelial cell health to have a corneal flap.

In this patient, therapeutic lamellar keratomileusis, which entails removing tissue for therapeutic reasons under a lamellar flap of corneal tissue, would be medically indicated. This patient is likely to gain best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and balance between the eyes with an ability to function in spectacles again. This should be medically indicated. Again, an unlisted procedure code (66999) is the best choice to report these surgical procedures, supported by a claim describing irregular astigmatism (367.22), aniseikonia (367.32), corneal guttata (371.57) and status post corneal transplant (V42.5).

If the patient in this case didn't have adequate corneal thickness or endothelial cell health to support a corneal flap, but his presentation was otherwise the same, phototherapeutic keratectomy would be a good option instead, using the same coding listed above.

• Case #4: A corneal transplant leaves a patient with high irregular astigmatism and anisometropia, poor vision in spectacles and contact lens intolerance. Wound alignment shows wound override to a small to moderate degree, and not enough to warrant wound resuturing or repeat penetrating keratoplasty in this eye.

In this patient, therapeutic CK would be medically indicated, as he is likely to gain BCVA and balance between the eyes with an ability to once again function in spectacles or contact lenses. This procedure would be reported as an unlisted anterior segment procedure (66999) and would be supported by a claim describing irregular astigmatism (367.22), aniseikonia (367.32) and mechanical complication of corneal graft (996.51).

Cosmetic Refractive Procedures

To help draw the line between cosmetic and therapeutic procedures, following are cases that would have to be paid for by the patient (See Table 2 for examples of complex cosmetic refractive procedures and their charges.)

• Case #1: A 55-year-old patient comes in with the chief complaint of an interest in reducing her dependence on glasses and contact lenses. Her refractive error is -8 D and corneal thickness is 550 µm in each eye. There's evidence of anterior basement membrane dystrophy on slit lamp exam, yet the patient has no history of recurrent erosions or decreased vision due to irregular astigmatism from the anterior basement membrane dystrophy.

After discussing the risks and benefits with the patient, and because this patient's main interest is reducing her dependence on glasses or contact lenses, the surgeon decides to proceed with PRK with use of mitomycin-C to reduce the incidence of haze or scar tissue formation. In such a case, we might typically still apply a small amount of laser treatment to the peripheral cornea where the epithelium is most likely loose in order to reduce the incidence of recurrent erosion symptoms postoperatively. From the standpoint of billing for this procedure though, it's a PRK.

Because PRK for correction of the refractive error is the main reason for the treatment, the schedulers, billers, technicians and patient understand that this is a refractive procedure, which the surgeon feels is for a refractive indication, not a therapeutic one. In our system, this patient would be charged the standard fee for a refractive correction. The outcomes are relatively similar in this situation to those patients who don't have anterior basement membrane dystrophy, because their refractive error is typically very definable with manifest refraction and wavefront testing.

• Case #2: A 35-year-old man who sees well in glasses and contacts wants to reduce his dependence on them.

On exam, the physician finds keratoconus, but notes that it isn't causing any visual disability. The patient's refractive error is -4.00 + 3.00 x 135. His corneal thickness is 480 µm in each eye. The patient has no difficulty driving in contact lenses or glasses. After discussing the possible risks and benefits of surgery with the patient, both physician and patient agree to proceed with Intacs and CK.

Because this patient's main interest is reducing his dependence on glasses and contact lenses, the physician chooses to use a "complex-case" Intacs and CK. The complex designation indicates a procedure on a patient that has complicating factors that make the surgery more challenging, such as keratoconus, and warrants a higher charge and some more patient counseling.

From the standpoint of naming this procedure though, it's an Intacs and CK. Despite the pathologic diagnosis of keratoconus, the patient has no disability such as glare, decreased BCVA or intolerance to glasses or contacts, and therefore, the procedure is considered cosmetic and the patient has to pay. The primary diagnosis code is 367.10 and 367.21, even though the codes 371.60 and 367.22 may be appropriate secondary ones.

• Case #3: A patient has had a successful PK in both eyes for keratoconus and has a refractive error of

-3.00 + 1.00 x 90 in both eyes. He has good bilateral BCVA of 20/20 with spectacles and wears contact lenses occasionally. He's interested in decreasing his dependence on glasses and contact lenses. His endothelial cell counts are normal.

After he and his surgeon discuss risks, benefits and alternatives, both decide to proceed with LASIK. Because the patient's main motivation is reducing his dependence on glasses and contact lenses, the procedure the surgeon chooses is a complex-case LASIK. Despite the patient being post PK as well as having keratoconus, he has no disability from his disease state. To qualify for therapeutic application of the procedure, he would need to have decreased BCVA, symptoms from irregular astigmatism such as glare or starbursts, symptomatic anisometropia and intolerance to glasses and contact lenses.

We hope that a clearer understanding of the distinction between cosmetic and therapeutic refractive surgery eventually leads surgeons and health insurers to a rational coverage policy. Currently, refractive surgery is almost always deemed to be not covered without a second thought. However, refractive procedures like LASIK may actually be the most viable options for correcting debilitating visual outcomes of pathologic conditions or previous surgeries such as PK or cataract surgery.

Dr. Hardten is an adjunct associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota, and is director of fellowship training and research at his practice, Minnesota Eye Consultants. He may be reached at drhardten@mneye.com.

Dr. Hira practices at Minnesota Eye Consultants. She may be reached at nkhira@mneye.com.

Mr. Corcoran is president of Corcoran Consulting Group, a practice management consulting firm specializing in reimbursement issues for ophthalmology and optometry. He may be reached at kcorcoran@corcoranccg.com.

1. Johnson, MP, Corcoran, KJ. A Fresh Look at Cataract Surgery Reimbursement. Administrative Eyecare 2003;12:4.

2. Brooks SE, Johnson D, Fischer N. Anisometropia and binocularity. Ophthalmology 1996;103:1139-1143.

3. Ewalt HW Jr. A discussion of one hundred cases of aniseikonia. Aust J Optom October 1964:276.

4. Alio J, Salem T, Artola A, Osman A. Intracorneal rings to correct corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:9:1568-74.

5. Colin J, Velou S. Current surgical options for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:2:379-386.

6.Hardten DR, Chittcharus A, Lindstrom RL. Long-term analysis of LASIK for the correction of refractive errors after penetrating keratoplasty. Tr Am Ophthalmological Soc 2002;100:143-150;150-152 (discussion).

7.Lima G da S, Moreira H, Wahab SA: Laser in situ keratomileusis to correct myopia, hypermetropia and astigmatism after penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: A series of 27 cases. Canadian J Ophthalmol 2001;36:7:391-396;396-397 (discussion).

8. Nassaralla BR, Nassaralla JJ. Laser in situ keratomileusis after penetrating keratoplasty. J Refract Surg 2000;16:4:431-437.

9. Rybintseva LV, Sheludchenko VM. Effectiveness of laser in situ keratomileusis with the Nidek EC-5000 excimer laser for pediatric correction of spherical anisometropia. J Refract Surg 2001;17:S224-8.

10. Duffey RJ, Leaming D. US trends in refractive surgery: 2001 International Society of Refractive Surgery Survey. J Refract Surg 2002;18:2:185-188.

11. Boxer Wachler BS, Chandra NS, Chou B, Korn TS, Nepomuceno R, Christie JP. Intacs for keratoconus. Ophthalmology 2003;110:5:1031-40, 2003.

12. Colin J, Cochener B, Savary G, Malet F. Correcting keratoconus with intracorneal rings. [comment]. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:8:1117-22.

13. Colin J, Cochener B, Savary G, Malet F, Holmes-Higgin D. INTACS inserts for treating keratoconus: One-year results. Ophthalmology 2001;108:8:1409-14.

14. Kymionis GD, Siganos CS, Kounis G, et. al. Management of post-LASIK corneal ectasia with Intacs inserts: One-year results. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:3:322-326.

15. Lovisolo CF, Fleming JF. Intracorneal ring segments for iatrogenic keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis or photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg 2002;18:5:535-541.

16. Siganos CS, Kymionis GD, Kartakis N, Theodorakis MA, Astyrakakis N, Pallikaris IG. Management of keratoconus with Intacs. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:1:64-70.

17. Hardten, DR. Treatment of keratoconus using intracorneal ring segments and conductive keratoplasty. Presented at the 2003 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery meeting, 2003; ASCRS Abstract book:p.162.

18. Hamilton, DR, Hardten, DR, Lindstrom, RL. Conductive and Thermal Keratoplasty. In: Krachmer J, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. St. Louis: Mosby, 2003: in press.

19. Fagerholm P. Phototherapeutic keratectomy: 12 years of experience. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica 2003;81:1:19-32.

20. Hardten, DR., Ehlen, TJ. Management of Recurrent Corneal Erosions. In: Albert, Barney, Brightbill, et al., eds. Ophthalmic Surgery: Principles and Techniques. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Science, 1999.

21. Maini R, Loughnan MS. Phototherapeutic keratectomy re-treatment for recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:3:270-2.

22. Moniz N, Fernandez ST. Efficacy of phototherapeutic keratectomy in various superficial corneal pathologies. J Refract Surg 2003;19:S243-6.

23. Stewart OG, Morrell AJ. Management of band keratopathy with excimer phototherapeutic keratectomy: visual, refractive, and symptomatic outcome. Eye 2003;17:2:233-7.