Today, minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries, or MIGS, are being adopted by many general ophthalmic surgeons. Unlike many glaucoma surgeries—some of which are complex and involve significant postoperative care—MIGS tend to be straightforward, involving minimal risk and minimal follow-up. However, they also usually have a less-dramatic impact on intraocular pressure, making them best-suited for patients with early glaucoma—and for surgeons less interested in doing extensive patient follow-up.

Michele C. Lim, MD, professor of ophthalmology and vice chair and medical director of the U.C. Davis Eye Center in Sacramento, California, points out that many of the MIGS devices have been specifically marketed for general ophthalmologists. “Comprehensive ophthalmologists tend to do a lot of cataract surgery, and they usually see patients who have glaucoma at the earlier stages of disease,” she notes. “Because many of the MIGS to date work well for early to moderate glaucoma, the companies usually market their MIGS products toward those ophthalmologists.”

Dr. Lim notes, however, that the use of these devices has been somewhat limited by the nature of the FDA approvals. “Some of the devices, like the iStent and the CyPass, were only approved for reimbursement when performed in combination with cataract surgery,” she says. “That’s kind of a shame, because patients who’ve already had cataract surgery could probably still benefit from these devices.”

Alan Crandall, MD, a clinical professor, senior vice chair of ophthalmology and director of glaucoma and cataract in the Department of Ophthalmology at the Moran Eye Center—part of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City—agrees. “Most MIGS have to be combined with cataract surgery if you want to get reimbursed,” he says. “Using those MIGS as standalone procedures would require getting the patient to pay out-of-pocket. For that reason I suspect most cataract surgeons will use them exclusively in combination with cataract surgery.”

Here, surgeons well-acquainted with the MIGS procedures share their answers to key questions that non-glaucoma-specialist surgeons often ask when thinking of adding one or more MIGS procedures to their armamentarium—especially as an option to combine with cataract surgery.

1. Which MIGS procedure should I learn?

“I haven’t seen any surveys regarding how many general ophthalmologists are using MIGS, or which ones they’re using,” notes Dr. Lim. “However, based on the referrals I get, I’d say that most general ophthalmologists are doing the iStent. That’s most likely because it’s one of the easier and safer MIGS to implant. Some of the other MIGS are more complex, and for the most part I’ve only seen glaucoma specialists do them.”

Most MIGS surgeons seem to agree that a trabecular meshwork stent is a good place for a general ophthalmologist to start. “In this situation [when performing MIGS with cataract sur-

gery], I’m a strong proponent of MIGS procedures that work synergistically with the effects of phacoemulsification,” says Thomas W. Samuelson, a founding partner and attending surgeon at Minnesota Eye Consultants in Minneapolis and an adjunct professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota. “We now have the results of five major, large-scale, prospective randomized MIGS trials in the literature. In all five of these trials, the control arm—i.e., phaco alone—lowered IOP significantly. The average composite IOP reduction in the control group of these papers was more than

5 mmHg. Thus, for combined surgery, I select MIGS procedures that are least likely to adversely affect that benefit and most likely to be synergistic with normal outflow physiology, such as a canal-stenting device. I’m less likely to use an ablative technique.

“The opposite might be said for procedures in pseudophakic eyes, where the cataract card has already been played,” he adds. “Of course, canal stenting devices aren’t labeled for standalone surgery anyway—at least for now.”

“By far, conventional outflow enhancement with MIGS is the safest way to surgically lower IOP, although it’s limited by episcleral venous resistance,” says Ike Ahmed, MD, FRCSC, assistant professor of ophthalmology and research director at the Kensington Eye Institute at the University of Toronto, and a professor at the University of Utah. “Most MIGS procedures—including stenting, cutting and dilating approaches—work with the trabecular meshwork/Schlemm’s canal pathway, and these procedures can be relatively efficiently combined with cataract surgery.”

|

Dr. Crandall believes most general ophthalmologists would have the greatest success with trabecular meshwork stents. “There are a number of MIGS outflow devices to choose from, including iStent, iStent Inject and Hydrus,” he points out. “The other MIGS options all have some potential drawbacks for a general cataract surgeon. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation, transscleral cyclophotocoagulation and micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation are all reasonable choices for combining with cataract surgery, but the general ophthalmologist has to consider the cost of the machine, as well as the fact that the procedure may need to be redone. MIGS procedures that open the canal—OMNI, GATT, the Kahook Dual Blade and so forth—require wash-out and further care that most general ophthalmologists may not be comfortable with. And some of the others, such as MIGS devices that use the sub-Tenon’s space, can be technically challenging, unless the surgeon has the right kind of experience. If the surgeon is comfortable performing trabeculectomy, the latter would be reasonable options.” [More on all of these options below.]

“A surgeon’s choice of MIGS procedure should be customized for each individual patient,” says Vikas Chopra, MD, medical director of the Doheny Eye Centers Pasadena, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and the director of glaucoma research at the Image Reading Center at the Doheny Eye Institute. “That being said, I think it’s probably a good idea to initially try to enhance the patient’s own outflow system rather than bypass it. I’d recommend a trabecular meshwork bypass procedure as the first-line choice, especially in patients with mild to moderate glaucoma and/or a desire to reduce topical medication burden. Dr. Crandall believes most general ophthalmologists would have the greatest success with trabecular meshwork stents. “There are a number of MIGS outflow devices to choose from, including iStent, iStent Inject and Hydrus,” he points out. “The other MIGS options all have some potential drawbacks for a general cataract surgeon. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation, transscleral cyclophotocoagulation and micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation are all reasonable choices for combining with cataract surgery, but the general ophthalmologist has to consider the cost of the machine, as well as the fact that the procedure may need to be redone. MIGS procedures that open the canal—OMNI, GATT, the Kahook Dual Blade and so forth—require wash-out and further care that most general ophthalmologists may not be comfortable with. And some of the others, such as MIGS devices that use the sub-Tenon’s space, can be technically challenging, unless the surgeon has the right kind of experience. If the surgeon is comfortable performing trabeculectomy, the latter would be reasonable options.” [More on all of these options below.]

“However, there may be exceptions,” he notes. “For example, an older, monocular patient might not be a good surgical candidate because of systemic or ocular health issues. In that situation, it would make sense to consider a non-incisional procedure like micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation first.”

Dr. Lim points out that it’s important to base your choice of MIGS procedure on the literature—while also keeping in mind the limits of the available studies. “Surgeons shouldn’t base MIGS choices on hype, word-of-mouth or the latest trend,” she says. “It’s important to perform a review of the literature first. Of course, one caveat when reviewing MIGS literature is that most clinical trials report short-term outcomes; very few have followed patients beyond 36 months. Longer studies might show even better efficacy—or they might find the opposite. I think we saw that with the original iStent. The data did show superiority with pressure control after one year, but when the two-year study came out, you could see that the pressure control started to wane.

“In terms of different treatment modalities that have the same goal, such as placing an iStent vs. placing a Hydrus, there are no comparative studies at this time showing that one is superior to the other,” she adds. “However, if you’re a surgeon who sees a great deal of glaucoma, I think you should explore multiple treatment options.”

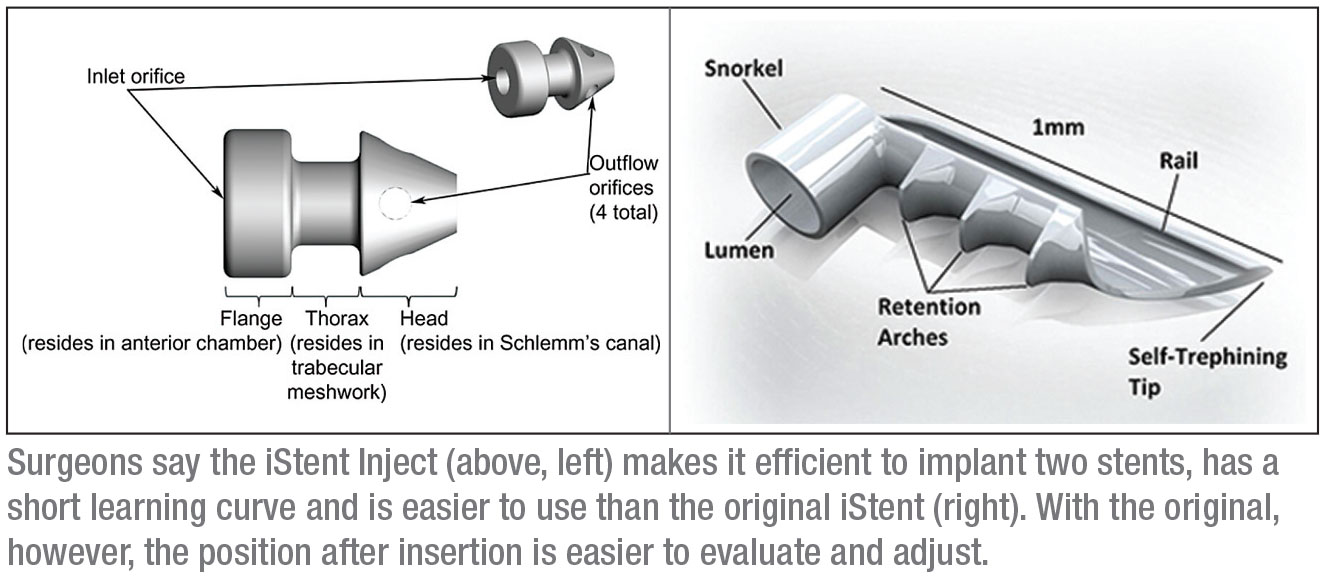

2. If I choose the iStent, which should I start with: the iStent or the iStent Inject?

Dr. Ahmed explains that the original iStent and the iStent Inject each have their own rationale. “First of all, the iStent Inject makes it efficient to put two implants in,” he says. “We believe that does enhance the IOP-lowering ability of the intervention. Another advantage is that the Inject has a shorter learning curve, which is helpful for surgeons that haven’t placed many of the original iStents. I suspect it’s already motivated many comprehensive ophthalmologists to try it.

“However, I’ve had a lot of experience with the classic iStent,” he continues. “Here in Canada I often implant two of the original iStents, and I’ve had good success with that approach. With the first-generation iStent, I’m sure of the placement and I can easily make adjustments. However, when implanting the original

iStent, the need to use lateral motion and the turning of the hand poses a technical challenge for a number of surgeons; the iStent Inject obviates that. Another difference between them is that gauging the depth of the iStent Inject implants can be a bit of a challenge. With the original iStent, you have a better idea of whether or not the stent is inserted into the tissue correctly, and you can adjust it if necessary.

“In short, there are unique features and advantages to both devices,” he concludes. “However, if you’re a surgeon who’s never done MIGS procedures, I think you’ll find the iStent Inject easier to adapt to, with a shorter learning curve.”

| “Surgeons who aren’t interested in bleb management should stick to trabecular-meshwork MIGS.” —Ike Ahmed, MD |

3. What about cyclophotocoagulation?

Dr. Lim says she considers endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation and transscleral cyclophotocoagulation to be MIGS procedures. “I know some people would argue with labeling these procedures MIGS, because they use a laser,” she says. “However, in a way, transcleral cyclophotocoagulation is the ultimate MIGS procedure. It’s one of the most noninvasive things you can do. Then there’s the micropulse CPC, which is being marketed as even less invasive than continuous-wavelength TSCPC. Both CPC and TSCPC have worked well for many of my patients. ECP is more invasive, of course, but many doctors do it in conjunction with cataract surgery.

“The downside of these procedures is that most comprehensive ophthalmologists don’t have access to those types of lasers,” she adds. “In fact, even some glaucoma specialists I know refer patients to us for that because of laser access issues.”

Dr. Ahmed notes that the newest iteration, micropulse cyclophotocoagulation, is still a novel treatment. “It has some potential to reduce the side effects associated with other forms of CPC,” he notes, “and I do think cycloablation may have a role earlier in the course of treatment than we’ve traditionally used it, especially with the ability to do things in a safer manner. However, with this new approach I think we still need to learn more about the proper dosing and the right treatment for a given patient; we need more studies to determine the optimal settings. What’s the right duty cycle? The right energy delivery? The right timing? I don’t believe we’re ready to use micropulse CPC to treat very early glaucoma, or as initial therapy.”

4. What about the subconjunctival MIGS?

“We have new classes of MIGS that bypass the angle completely and shunt fluid into the subconjunctival space, as a trabeculectomy or tube would do,” notes Dr. Lim. “They’re meant to address moderate to severe levels of glaucoma. The two things in this category are the XEN gel stent and the not-yet-approved InnFocus Microshunt. They’re still considered MIGS because they require less dissection of tissue than traditional surgeries. However, both of these do require manipulating the conjunctiva and injection or application of mitomycin-C. That puts them in a different class from the iStent or Hydrus.

“In general, I think the trickier and less-well-understood the procedure, the fewer comprehensive doctors you’ll find doing it,” she continues. “For example, the XEN is challenging to implant, and it’s a bleb-forming procedure that requires the use of mitomycin-C. Most comprehensive doctors don’t have a lot of experience with MMC, so I think you’re less likely to see a non-specialist using the XEN. That goes for the InnFocus Microshunt as well, which isn’t FDA-approved, although there’s an ongoing U.S. clinical trial underway to try to gain approval.”

Dr. Ahmed agrees. “Microstenting and microshunting devices that involve the subconjunctival space fall into a somewhat different category from the others,” he says. “In those procedures, the management of the bleb is important, which means that managing those patients postop involves a different learning curve. Of course, a number of general and comprehensive ophthalmologists do feel comfortable managing a bleb, and for them I think performing these procedures is appropriate. For example, many comprehensive surgeons do trabeculectomies; that skill set would be perfect with this type of procedure. But if you’re not accustomed to managing a bleb, these procedures will be challenging. Surgeons who aren’t interested in bleb management should stick to trabecular-meshwork MIGS.”

Dr. Lim notes that these more complex MIGS represent an exciting shift in where MIGS is going. “They give us options for people with more advanced levels of glaucoma,” she points out. “We’ve learned from the previous MIGS that even if you bypass the trabecular meshwork, you’re still not likely to get pressures below the mid-teens. People who have significant glaucoma need lower pressures than that. These newer devices are meant to provide treatment options that can compete with trabeculectomy or tube shunts.”

5. Should I offer more than one MIGS procedure?

”Whether a general ophthalmologist should add more than one MIGS procedure to his or her armamentarium depends on several factors,” says Dr. Chopra. “First, how comfortable are you with the type of procedure you’re considering adding? Second, are you willing to manage any potential intraoperative and postoperative complications associated with the procedure? And finally, do you have enough surgical volume to allow you to manage the learning curve and continue to get better at the procedure?”

|

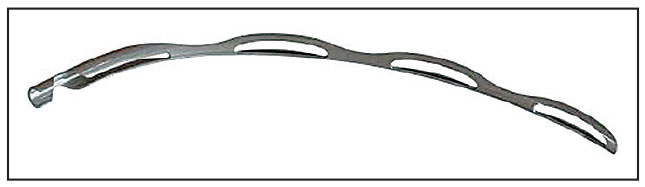

| The Hydrus Microstent maintains the patency of Schlemm’s canal and tensions the canal tissue, improving outflow across a significant portion of the canal. |

“The priority should be to be good at one MIGS procedure,” says Dr. Ahmed. “Ideally, you should have a go-to MIGS and a go-to subconjunctival procedure, giving you two different mechanisms of action. Once you get very good at one MIGS procedure, then you may want to expand a little bit and try some others, just to see if there’s a difference in efficacy or adverse events. But first it’s important to become good at one procedure.”

“I’d recommend becoming comfortable with a canal-stenting device, or at minimum a canal ablation procedure,” says Dr. Samuelson. “Once you’ve mastered the first one, others are far easier to add. Transscleral surgery is a more significant level of commitment.”

6. In which of my cataract cases should I consider adding MIGS?

“Understanding when it’s appropriate to recommend MIGS is an important issue,” says Dr. Lim. “I think the iStent is sometimes used in patients that don’t really need it, for example, or in patients whose glaucoma is too severe to benefit from it. It’s important to read the literature and understand when it’s appropriate to implant these devices.

“The FDA put out a guidance paper that talks about who should be included in clinical trials for MIGS and who should be excluded,” she continues. “One of the excluded groups was people with ocular hypertension. I think the FDA felt that these people should not be subjected to the risk of MIGS surgery. They also recommended not including people with severe glaucoma, because you don’t want to put people like that at risk by using an investigative device that has no known track record.

“The point,” she concludes, “is that surgeons need to thoughtfully consider who they offer MIGS to. One shouldn’t perform a MIGS procedure on every patient because they have an IOP problem or glaucoma. One needs to weigh the risks and benefits, as one would with any other surgery.”

Dr. Samuelson says his decision about whether to add MIGS to a cataract surgery depends on the patient’s disease status. “If the patient is being actively treated for glaucoma, or needs to be treated for glaucoma, I’d perform a combined procedure,” he says.

Dr. Crandall agrees. “MIGS shouldn’t be used unless the patient has a diagnosis of glaucoma and is being treated for it,” he says. “In that situation, there’s no harm, no foul, so to speak, if you add a MIGS procedure to the cataract surgery—although we always need to consider the cost to the patient.”

Is there a specific level of disease at which a surgeon should automatically consider adding MIGS? Dr. Chopra says no. “The decision to add MIGS to cataract surgery has to be individualized,” he says. “It should be dictated by the level of glaucoma, as well as the patient’s ability to tolerate topical anti-glaucoma medications. The goal of adding MIGS to cataract surgery might be to achieve a lower IOP, to maintain the same IOP with a reduction in the medication burden, or to address the patient’s topical medication non-compliance, which is quite common. Less-invasive procedures may be safer, so in general I prefer a stepwise approach to choosing a surgical treatment.”

Dr. Ahmed agrees that many factors should be considered. “The decision about whether to add a MIGS procedure to cataract surgery should be based on the disease state; the stability of the disease; the age of the patient; the number of drops the patient is using; how well the drops are tolerated; and how compliant the patient is,” he says. “You may have a patient who’s on one drop but never uses it. Without that drop, his pressures might be 28 mmHg and at risk of getting worse. If you’re performing cataract surgery on that patient, you should consider adding MIGS. Generally, the more drops the patient is on, the more potential value MIGS has, because it may reduce the drop load. But even patients who are only on one medication have a good chance of getting off of their medication with a MIGS procedure.

“At the same time, we do need to remember that cataract surgery will lower IOP on its own,” he notes. “It just seems to be the case that phaco plus MIGS has a greater likelihood of getting patients off of their medications, or resulting in the need for fewer drops. You might say to a patient: ‘I can do a procedure that’s pretty much as safe as cataract surgery alone, but there’s a greater chance that you’ll be able to get off of medication. The chance of that happening might be 50 percent with cataract surgery alone, but 85 percent if I add MIGS.’

“Basically, I think any time you’re performing cataract surgery on a patient who has glaucoma, you should at least consider adding a MIGS procedure,” he says. “If it might help the patient reach the right target pressure and reduce medication use, that person is a candidate. That’s a pretty wide potential range of patients.”

Dr. Ahmed adds that factors such as the system, payer and the patient’s quality of life are important to take into account. “You have to consider the cost-effectiveness of adding a second procedure,” he notes. “If the patient just has ocular hypertension or very early disease, or the patient is compliant with a minimal amount of medication and 80 years old, maybe adding MIGS wouldn’t be cost-effective. The other side of the coin is a patient who has very bad disease and is uncontrolled. That patient should get something more aggressive than a trabecular-meshwork MIGS, such as a subconjunctival procedure, whether it’s subconjunctival MIGS or a trabeculectomy. A trabecular-meshwork MIGS wouldn’t be enough for someone who’s progressing and needs a very low pressure.”

7. Should the severity of the glaucoma affect my choice for a given patient?

Dr. Samuelson says his usual choice of a canal-based MIGS procedure to add to cataract surgery might be modified based on current disease severity and his best estimation of the likelihood of future progression. “I generally prefer the stealth nature of the canal-stenting devices,” he says. “The milder the disease and the closer the outflow system is to normal, the less I want to disturb tissue. The canal-stenting devices cause the least tissue disruption. For me, for now, this means using the iStent.

“On the other hand, the more significant the disease, presumably indicating worse outflow system functionality, the more I’m willing to disrupt tissue,” he continues. “The Hydrus spans more of the coveted inferonasal portion of the canal, which, on the positive side, should convey more device-influenced outflow. However, it’s also more tissue-disruptive. So when selecting among in-dwelling canal devices, I tend to use focal stenting—i.e., the iStent—for lesser disease, and more expansive stenting—i.e., the Hydrus—as I move up the spectrum of disease severity.”

Dr. Samuelson adds that he tends to reserve ablative or incisional canal procedures for standalone interventions without coincident cataract surgery. “In those situations I’ve grown increasingly satisfied with the OMNI device, which can dilate the entire 360 degrees of the canal or a portion thereof, and lets me incise as much of the canal as I wish,” he says. “The

Ellex iTrack and the Kahook Dual Blade are also very reasonable choices in this setting.”

Dr. Lim notes that when obstruction of the trabecular meshwork is part of the disease process, MIGS procedures that strip away tissue to unroof Schlemm’s canal might be a good choice. “Patients that could benefit from this might include those with pigment dispersion glaucoma, uveitic glaucoma and maybe pseudoexfoliation,” she says. “I haven’t used the Kahook Dual Blade yet, but I see it as a reasonable option whenever the problem involves an obstruction of the trabecular meshwork.”

8. Which MIGS works best in the presence of inflammation?

Dr. Samuelson says that inflammation can be an important determinant of the MIGS procedure he chooses. “For example, if a patient is in need of chronic, ongoing steroid therapy, I’m less likely to select a canal-based procedure because, collectively, those procedures are more associated with steroid-related increases in intraocular pressure,” he explains. “I’m more likely to perform a subconjunctival outflow MIGS such as a gel stent in this setting. If the disease is severe enough, I might resort to a trab or tube.

|

|

|

“If a general ophthalmologist performing cataract surgery is faced with a glaucoma patient on chronic steroids, I’d recommend skipping canal-based MIGS and performing XEN or trabeculectomy,” he says. “If the surgeon is uncomfortable with these procedures, I’d consider referring the patient to a glaucoma specialist.”

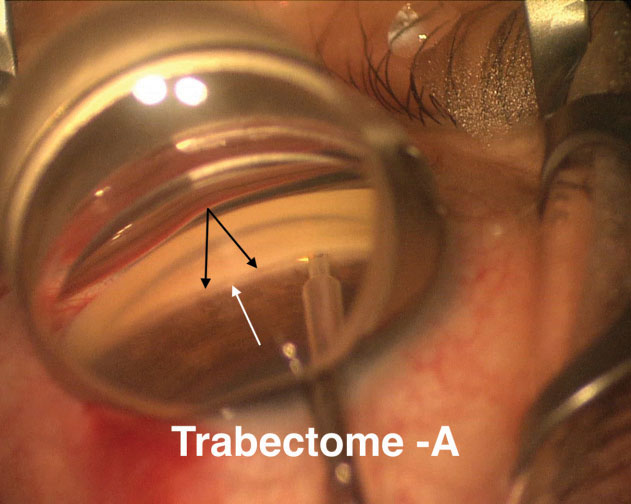

Dr. Chopra agrees that combining MIGS with cataract surgery in the setting of ocular inflammation can be quite complicated. “You may need to perform concurrent surgical maneuvers such as disrupting posterior synechiae, using pupillary dilators and managing peripheral anterior synechiae,” he points out. “Trabecular bypass procedures such as Trabectome and goniotomy with the Kahook Dual Blade can be successful in these situations, but it’s important to aggressively control inflammation postoperatively to reduce the risk of trabecular cleft closure due to the development of posterior synechiae.”

9. Should the MIGS I consider adding be influenced by the condition of the cataract and zonules?

“If you detect weak zonules, either preoperatively or intraoperatively, the risk of vitreous loss is greater,” Dr. Chopra notes. “In that situation, the benefits of MIGS have to be carefully weighed against the risks of the procedure. It may be safer to avoid MIGS and consider referral to a glaucoma subspecialist for a more traditional glaucoma procedure such as an aqueous tube shunt implantation. In these surgeries the focus should be on successful, safe cataract removal, paying special attention to avoiding iatrogenic worsening of the zonulopathy. It may be better to ‘live to fight another day’ and perform the cataract and glaucoma procedures sequentially instead of concurrently.”

Dr. Chopra points out that some cataracts might warrant performing the MIGS procedure before the cataract surgery. “If a patient has a very dense cataract that may require longer cataract surgical time and more phacoemulsification power, as well as greater irrigation and aspiration volume, you may be left with significant corneal edema by the end of the cataract procedure—especially over the incision,” he says. “In that situation, it may be prudent to consider performing the trabecular bypass procedure before cataract surgery when the cornea is most clear. If you wait until after the cataract surgery is complete, proper visualization of the angle using the gonioscopic lens may be more challenging because of the corneal edema.”

Dr. Ahmed believes the complexity of the cataract is a separate issue. “Combining the surgery with MIGS doesn’t necessarily make it more difficult to manage the complexity of the cataract surgery,” he says. “Of course, in some cases it could make things more difficult; some MIGS procedures, for example, have a higher chance of causing bleeding in the eye or hyphemas. That could impact the surgeon’s ability to manage a patient who needs more complex cataract surgery, such as a patient with weak zonules, so the surgeon has to consider that. However, in our clinic we have a lot of experience with complex cataract surgery, such as cases involving trauma or pseudoexfoliation. Those patients often have glaucoma associated with their underlying diseases, and most of them do quite well with MIGS. So why not combine the surgeries?”

| These surgeries require mastery of gonioscopy and a thorough knowledge of angle anatomy. |

What other strategies will help ensure success?

Surgeons offer these pearls to general ophthalmologists who are adding MIGS to their cataract surgery options:

• Do your homework before performing any MIGS surgery. Practice makes perfect,” says Dr. Chopra. “I would strongly encourage any surgeon thinking of adding MIGS to their repertoire to watch surgical videos of the procedure in question to learn the technique; work with industry reps to do ‘personalized wet labs’; sign up for surgical wet lab training at meetings like ASCRS and AAO; and talk to colleagues and glaucoma specialists who are well-acquainted with the procedure, to learn tips and surgical pearls. “

• Practice gonioscopy and know the angle anatomy. All MIGS surgeons agree on one thing: These surgeries require mastery of gonioscopy and a thorough knowledge of angle anatomy. “We get referrals from doctors who implant iStents, and we sometimes find that the placement is incorrect,” says Dr. Lim. “The device is either poorly positioned or not in the trabecular meshwork at all. So it’s important to perform gonioscopy often, to become familiar with the anatomy of the angle.”

“Understanding the surgical anatomy—especially the iridocorneal angle—is incredibly important to a successful MIGS procedure,” agrees Dr. Chopra. “That’s often underappreciated. That’s why achieving expertise in clinical and surgical gonioscopy is essential.”

However, Dr. Samuelson says this shouldn’t cause surgeons to be put off. “MIGS procedures are very delicate,” he says. “They involve some of the most precise maneuvers we do as anterior segment surgeons. However, if you’re an accomplished cataract surgeon, you’ll be able to learn and master MIGS. Just don’t try MIGS until you’re very confident with intraoperative gonioscopy. MIGS procedures are very safe, but significant risk may be involved when they’re attempted without good visualization.”

Dr. Ahmed agrees, noting that the positioning of the patient on the table is part of good visualization. “The most important thing, in order to succeed with MIGS procedures, is to hone in on the setup and positioning of the patient, and the visualization—meaning gonioscopy—in the clinic and the OR,” he says. “You can learn these things without even doing MIGS. You can practice with cataract eyes, just tilting the microscope and the head of the patient at the end of the case, to get a better view.”

Dr. Lim adds that an excellent way to improve your angle structure knowledge is to visit gonioscopy.org. “This is a fabulous resource, created by Lee Alward, MD, at the University of Iowa,” she notes.

• Weigh the risks (usually limited with MIGS surgery) against the benefits. Dr. Lim points out that, as with any surgery, there’s always some amount of risk to weigh against the potential benefits. “Sometimes the risks take a while to become apparent,” she says, noting that this is another reason to pay attention to the literature. “For example, with the CyPass, adverse events were noted before it was recalled—issues that were not apparent in the original COMPASS trial. Some surgeons reported an unexpected myopic shift, while others witnessed a sudden, acute rise in pressure months after the CyPass was implanted. Another example is the iStent. The adverse events reported in the literature were fairly minimal, but I did have one patient who bled profusely during an implantation, and that led to a very high, prolonged IOP rise.”

• Have realistic expectations. “It’s important that all surgeons and patients and payers understand that with our current level of knowledge, anything we do to address glaucoma tends to wear off over time, at least to some degree,” Dr. Ahmed says. “That’s true of every option—drops, lasers, trabeculectomy, tubes and MIGS. It’s a result of the nature of the disease, and the way the eye recovers and heals after these surgeries. It shouldn’t surprise anybody, and it certainly hasn’t caused us to stop treating glaucoma.

“When we’re treating glaucoma, we continue to manage the patient over time,” he points out. “We go from one treatment to the next, to the next. The right algorithm and selection of drops and procedures and devices will hopefully stabilize intraocular pressure enough to prevent progression over the course of a patient’s lifetime. Accomplishing that may require multiple modalities, and the iStent and other MIGS are part of that paradigm—especially with their excellent track record of safety.”

Adding Value for Your Patients

“I think any surgeon doing cataract surgery should be able to offer MIGS to appropriate patients,” says Dr. Ahmed. “The safety of MIGS has been established, and the safety of combining cataract surgery with MIGS doesn’t seem to be much different than regular cataract surgery, which is important. Recovery time doesn’t seem to be any different either. Meanwhile, the potential benefits for the patient are significant. MIGS can help reduce the patient’s medication load, which can also enhance the patient’s visual recovery by improving the ocular surface, so patients end up seeing better. That can increase the patient’s quality of life, without much downside in terms of complications.”

“Some surgeons would say that MIGS shouldn’t be used at all,” notes Dr. Crandall. “They sometimes refer to these procedures as ‘MEGS,’ or ‘minimally effective glaucoma surgeries.’ I’m not in that group. Many of our patients have glaucoma that’s under control. If a MIGS procedure can get those patients off of even one medication, that’s a good thing. For that reason, I’m happy to see general ophthalmologists using MIGS.

“Again,” he adds, “experience is key. So, I’d suggest that most general ophthalmic surgeons interested in MIGS find a device that works for them and then become good at using it.”

“I’d encourage surgeons to do this,” Dr. Ahmed concludes. “There’s a technical learning curve that surgeons need to master, and appropriate patient selection is important. But I think the day is coming when a cataract surgeon who isn’t able to offer MIGS will be seen as behind the times. If a patient comes in with glaucoma and is taking a number of drops, you have a better chance of reducing his medication burden if you add MIGS to the cataract surgery. So why not offer it?” REVIEW

Dr. Samuelson is a consultant for Alcon Surgical, Johnson & Johnson Vision, AqueSys/Allergan, Equinox, Glaukos and Ivantis. Dr. Ahmed is a consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Equinox, Glaukos, Ivantis and Santen. Dr. Crandall is a consultant for Ivantis, Glaukos and Alcon. Dr. Lim is an investigator for Santen (which now owns the InnFocus device) and has been a speaker for Alcon. Dr. Chopra reports to relevant financial ties to any product mentioned.