It appears devastating and it truly is. A crescent, peripheral, corneal thinning and ulcerative process that—even though its progression can be slow—is marked by outcomes that can be extremely difficult to manage. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is known to be caused by a variety of conditions including infections, lid abnormalities, skin disorders, and autoimmune diseases. Nevertheless, one of the main autoimmune disease categories that causes PUK is vasculitides/collagen vascular disease.1,2 Nearly half of all non-infectious causes of PUK are due to a collagen vascular disease.6

Ophthalmologists play a significant role in the process of providing adequate care for vasculitic PUK patients. Any time one sees necrotizing scleritis and/or PUK in patients with pre-existing autoimmune systemic vasculitis, the vasculitis must be considered active until proven otherwise. These patients need urgent attention as prompt systemic medical intervention in many cases can save their lives.

Some of the challenges that ophthalmologists often face with vasculitic PUK include the clinical presentation, diagnosis and the appropriate workup. This review includes some of the main etiologies, characteristic clinical presentations, laboratory/clinical workups and treatments, as well as recommended follow-up patterns for vasculitic PUK.

Etiology

Autoimmune vasculitis is thought to be caused by circulating antibodies within the body, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Production of these compounds is usually T-cell mediated and the resulting inflammation can involve large, medium or small vessels.3,4 Even though the systemic inflammation caused by all of these autoimmune vasculitic diseases can result in some degree of ocular symptoms as well as the systemic manifestations, the majority of the ocular symptoms are usually noted with the medium- and small-sized vasculitic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis; systemic lupus erythematosus; relapsing polychondritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; and polyarteritis nodosa.5,6,9-11

Unlike the central cornea, which acquires its main nutritional resources from an avascular pattern, the peripheral cornea obtains a part of its nutritional requirements from the limbic capillary arcades, which extend about 0.5 mm toward the central cornea.7 This direct exposure of the peripheral cornea to the circulatory compounds, which in cases of vasculitis include inflammatory cytokines as well, is thought to be the main cause of the involvement of the peripheral cornea in systemic autoimmune vasculitic processes.6,7

Ocular Presentation of PUK

Ocular manifestations of vasculitis PUK can present with generalized symptoms and physical exam findings that usually are not specific to the exact underlying vasculitic disease. However, these symptoms and findings are usually specific and sufficient enough to raise the concern for an underlying systemic disease and further workup.

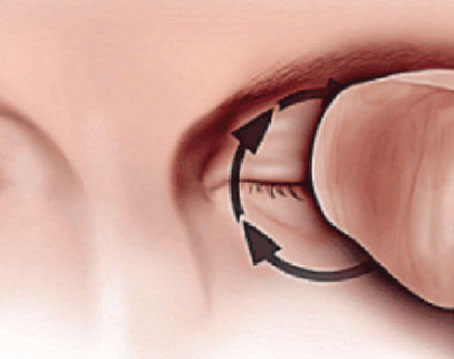

Initial presentation of vasculitic PUK usually involves juxtalimbal peripheral corneal stromal thinning overlying epithelial defect, and usually a line of stromal inflammation at the leading edge. There can also be an association with keratoconjunctivitis, episcleritis, anterior or posterior scleritis, and/or retinal vasculitis. But of these, the two most sight-threatening complications are scleritis and PUK. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis may begin as an area of corneal thinning which evolves into a corneal ulcer, and eventually has the potential for causing corneal melting and perforation from further thinning.8

It is significant to note that one of the main differentiating aspects between vasculitic PUK and the other types of corneal peripheral ulcerative diseases is the presentation of the systemic manifestations along with the corneal defects. As a result, it is highly beneficial for the ophthalmologist to obtain a comprehensive review of systems if suspicious for vasculitic PUK.6

Mooren’s ulcer can look very similar to vasculitic PUK, as well. However, there are three major features that differentiate the two diagnoses. First, patients with Mooren’s ulcer complain of severe eye pain, which can be out of proportion to the clinical exam. Second, Mooren’s ulcer does not have an associated scleritis, which may be seen in a PUK associated with collagen vascular disease. Third, Mooren’s ulcer is a diagnosis of exclusion and can be associated with hepatitis C and parasitemia, but not due to a collagen vascular disease. Therefore, a collagen vascular disease should be ruled out prior to reaching this diagnosis. Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa and relapsing polychondritis are main systemic disorders that are associated with small-vessel vasculitic PUK.

Clinical Presentation

Rheumatoid arthritis is a generalized, chronic, inflammatory polyarthritis with early morning stiffness and involvement of three or more joints (typically proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal or wrist joints).26 RA is the most common collagen vascular disease associated with peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a predominantly young female disease with arthritis that typically involves the hands. Most of these patients also develop a butterfly facial rash with erythema over the cheeks and nose. The rash usually appears after sun exposure and lasts a few days with frequent recurrences. Exposure to sun may exacerbate or even induce the first sign of lupus. Raynaud phenomenon, kidney disease (proteinuria), lung involvement (pleuritis), leukopenia, anemia and pericarditis are some of the other manifestations of SLE.6,26

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis with bloody or purulent nasal discharge and oral ulcers. WG can also involve pleuritis along with dyspnea and painful hematuria. Furthermore, WG patients can suffer from bone and cartilage destruction, causing saddle nose deformity and subglottic stenosis.26

Relapsing polychondritis is a collagen vascular disease with recurrent inflammation of the cartilaginous tissues, which most commonly targets the ear and nose. The affected auricles develop violaceous, erythematous appearance with sparing of the non-cartilaginous ear lobes. Recurrent inflammation of the cartilaginous portion of the ear results in loss of structural integrity, and subsequent “floppy ears.” The most life-threatening manifestation of this disease is involvement of the large airways, specifically the larynx, trachea and bronchi. This can cause significant obstructive lung disease, sleep apnea and post-obstructive pneumonia.6

Polyarteritis nodosa is a necrotizing nongranulomatous vasculitis arthralgia that can involve mononeuritis multiplex, cardiac and gastrointestinal involvement. Unlike WG, PAN patients do not have pulmonary and renal involvement. Hepatitis B or C can be associated with PAN, which is subdivided into three major forms: classic; Churg-Strauss syndrome; and an overlap syndrome of systemic necrotizing vasculitis.26 Some of the main clinical symptoms of PAN include lower extremity erythematic nodules on the skin, abdominal pain and a mononeuropathy multiplex involving both sensory and motor functions of peripheral nerves such as ulnar and radial nerves.26

Workup

A complete and comprehensive review of systems should direct the clinician toward the appropriate laboratory workup. After carefully excluding infectious etiologies, we suggest an auto-immune workup that includes complete blood count; antinuclear antibody; rheumatoid factor; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; chest X-ray; perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; hepatitis antibody panel; sedimentation rate; and C-reactive protein.6,9-11 A chest X-ray and radiograph of the sinuses may be indicated if one suspects SLE, WG or RP. This workup can be refined based on a detailed review of systems, and pertinent exam findings.

Very elevated titers of IgM-rheumatoid factor are present during the active vasculitis phase in rheumatoid arthritis. In systemic lupus erythematosis, ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies are present and are highly sensitive—90 percent and 70 percent, respectively. In Wegener’s granulomatosis, the sensitivity of the C-ANCA test is nearly 100 percent in patients with active disease.23 Relapsing polychondritis does not have any specific laboratory test available. Therefore, the diagnosis is strictly based on the clinical presentation.24 Of the three forms of polyarteritis nodosa cited earlier, classic polyarteritis nodosa usually results in medium-size vessel aneurysm formation, without renal and pulmonary involvement. Also, in classic PAN, ANCAs are typically absent, while the other two forms are ANCA-positive. In Churg-Strauss syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis, P-ANCA is positive in 50 percent of patients.25

Treatment

The main treatment of a vasculitic PUK is indeed treating the underlying systemic vasculitis, which, depending on the different categories/types, usually involves different types of systemic immunosuppressants. Most ophthalmologists are not commonly prescribing steroid-sparing immunosuppressants. So, the role of a specialist with expertise in managing immunomodulation therapy is crucial. Such a specialist, like a rheumatologist, can help in collectively administering systemic corticosteroids as well as initiating a steroid-sparing agent, or modify the current regimen in order to better control the active vasculitis.

From an ocular standpoint, aggressive lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears and topical antibiotic ointments such as erythromycin ophthalmic ointments are appropriate starting points. The next step can involve initiating a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor like doxycycline, which can also decrease collagenase activity and slow the corneal melting.6,18 If no epithelial defect is present, topical corticosteroids can also be initiated. One should be cautious using topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, as they can upregulate matrix metalloproteinase expression, increasing the likelihood of corneal melting.20,21 Topical fluoroquinolones should also be used with caution, as they can increase the upregulation of MMP expression.19,22 Such increased expression can also accelerate corneal thinning and melting.

Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be sufficient in relatively mild ocular involvement, such as episcleritis or non-necrotizing scleritis. However, in most cases, these therapies are not successful.12,13 PUK with vasculitis responds much better to oral corticosteroids. In fact, SLE-induced PUK has been shown to only respond to oral/systemic steroid therapies.14 The systemic corticosteroids are started at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day and tapered over several months, while a steroid-sparing agent is added or modified.15-17 Oral corticosteroids are usually tapered down to a low maintenance dose of 5 to 10 mg po daily. But, the steroid-sparing agent is maintained.

The appearance of a vasculitic PUK in light of a previously diagnosed autoimmune vasculitis is a clinical sign of an active/poorly controlled systemic inflammation. Therefore, immediate adjustments in systemic treatments should be considered in order to avoid other systemic complications. Ultimately, these patients are managed with long-term, steroid-sparing agents, such as antimetabolites, T-cell inhibitors, alkylating agents and biologic agents. The rheumatologist or the primary-care physician is involved in order to manage the systemic side effects of oral corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.

Follow-up

One of the main concerns with vasculitic PUK is the risk of corneal perforation and melting.2,6 As a result, the follow-up timeline of this complication is relevant to the progression of the disease once the treatment has been initiated. In general, as in the case with other types of corneal ulcerative diseases, vasculitic PUK cases would benefit from close follow-ups over five to seven days, until signs of symptomatic improvement as well as epithelial healing over the ulcerative area have been noted.

PUK may be the first sign of systemic vasculitis, and point to a life-threatening collagen vascular disease. It is diagnosed with a thorough review of system, appropriate clinical exam and laboratory testing. It is important to realize that the main treatment for vasculitic PUK is systemic immunosuppression with oral corticosteroids as well as steroid-sparing agents. It is imperative to seek prompt medical help from other medical care providers such as rheumatologists when it comes to managing the active systemic vasculitis and systemic interventions. These steps can not only save the ocular tissue, but ultimately, can save a patient’s life.

Dr. Tofigh and Dr. Kapur practice in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They thank Alejandro Navas, MD, MSc, associate professor of ophthalmology at the Institute of Ophthalmology “Conde de Valenciana,” Mexico City, for the use of Figures 1 and 2.

1. Mandell BF, Hoffman GS. Differentiating the vasculitides. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1994;20:409-442.

2. Foster CS, Gonzalez-Gonzalez L. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis. In: Melki S, Fava M, eds. Cornea and Refractive Atlas of Clinical Wisdom. Thoroughfare, NJ: Slack, 2011: 131-140.

3. Savage CO, Pottinger BE, Gaskin G, Pusey C. Autoantibodies developing to myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 in systemic vasculitis stimulate neutrophil cytotoxicity toward cultured endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 1992;141:335-342.

4. Ewert BH, Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies stimulate neutrophils to damage human endothelial cell. Kidney Int 1992;41:373-383.

5. Jennette JC, Ewert BH, Falk RJ. Do antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies cause Wegener’s granulomatosis and other forms of necrotizing vasculitis? Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993;19:1-14

6. Messmer EM, Foster CS. Vasculitic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1999;43:379-396.

7. Hogan MJ, Alvarado JA. The Limbus. In: Histology of the Human Eye: An Atlas and Textbook. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1971:112-182.

8. Stern G. Peripheral Corneal Disease. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005:339-352.

9. Kedhar SR, Belair M, Jun AS, Sulkowski M, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis with hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemia. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:852-853.

10. Myers JP, Di Bisceglie AM, Mann ES. Cryoglobulinemia associated with Purtscher-like retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:802-804.

11. Mondino BJ. Inflammatory diseases of the peripheral cornea. Ophthalmology1988,95:463-72.

12. Jayson MIV, Jones DEP. Scleritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1971;30:343-347.

13. Messmer EM, Foster CS: Destructive corneal and scleral disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Cornea 1995;14:408-417.

14. Foster CS. Ocular manifestations of the nonrheumatic acquired collagen vascular diseases. In: Smolin G, Thoft RA (eds). The Cornea. Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1983:344-367.

15. Bullen CL, Liesegang TJ, McDonald TJ, DeRemee RA. Ocular complications of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Ophthalmology 1983;90:279-290.

16. Foster CS. Immunosuppressive therapy for external ocular inflammatory disease. Ophthalmology 1980;87:140-150.

17. Foster CS. Ocular manifestations of the nonrheumatic acquired collagen vascular diseases. In: Smolin G, Thoft RA (eds). The Cornea. Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1983:344-367.

18. Smith VA, Cook SD. Doxycycline-a role in ocular surface repair. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:619-625.

19. Mallari PL, McCarty DJ, Daniell M, et al. Increased incidence of corneal perforation after topical fluoroquinolone treatment for microbial keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:131-3.

20. O’Brien TP, Li QJ, Sauerburger F, Revigilio NE, Rana T, Ashraf ME. The role of MMP in ulcerative keratolysis associated with perioperative diclofenac use. Ophthalmology 2001;108:656-659.

21. Gabison EE, Chastang P, Menashi S, Mourah S, et al. Late corneal perforation after photorefractive keratectomy associated with topical diclofenac: Involvement of matrix metalloproteinases. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1626:1631.

22. Sharma C, Velpandian T, Baskar Singh S, et al. Effects of fluoroquinolones on the effect of matrix metalloproteinases in debrided corneas of rats. Toxicol Mech Methods 2011; 21:6-12.

23. Nolle B, Specks U, Ludemann J, et al. Anticytoplasmic autoantibodies: Their immunodiagnostic value in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med 1989 Jul 1;111(1):28-40.

24. McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: Prospective study of 23 patients and a review of literalture. Medicine 1976;55:193-215.

25. Gross WL. Systemic necrotizing vasculitis. Bailliere Clinical Rheum 1997;11:259-284.

26. Klippel JH, ed. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, 11th ed. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 1997:1