It’s very well established that corneal collagen cross-linking is an effective way to strengthen the cornea and prevent the progression of keratoconus and ectasia. However, cross-linking appears to be potentially useful in several other ways as well.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of epi-off cross-linking is relatively limited in scope; it applies only to the UV light system and riboflavin solutions designed by Avedro, and only gives approval to its use in patients over the age of 14 who have been shown to have progressive keratoconus or post-surgical ectasia. Those limitations, of course, are the result of the nature of the studies upon which the approval was based. Meanwhile, outside of the United States other uses for cross-linking are common, and new ones are under investigation. In fact, many surgeons in the United States are using the procedure in ways that go beyond the officially sanctioned indications.

Here, surgeons with experience using cross-linking in off-label ways discuss their experiences and share what alternate uses currently look most promising.

Treating Young Patients

The FDA approval states that keratoconus patients receiving this treatment should be 14 years or older and have disease that’s progressing. However, many surgeons are treating patients younger than that—and they’re not waiting for clinical proof that the patient’s disease is progressing.

Parag A. Majmudar, MD, is associate professor of ophthalmology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and president and chief medical officer of Chicago Cornea Consultants. Dr. Majmudar began performing cross-linking in 2010; he’s done hundreds of cross-linking procedures, especially treating post-LASIK ectasia, and has worked with Roy Rubinfeld, MD, on the development of an effective epi-on cross-linking procedure. Dr. Majmudar notes that his practice has never worried too much about documenting progression before treating a patient. “After all the years that cross-linking has been done internationally, we really believe in the technology,” he says. “We know it’s going to help prevent problems, so we haven’t necessarily wanted to withhold treatment until progression has been documented. If a 14-year-old patient comes in with vision suddenly getting worse because of keratoconus, I don’t see any reason to wait and have him come back three months later.”

Dr. Majmudar also says his practice will treat patients as young as 8 years old. “The youngest keratoconus patient I’ve treated myself was 10 years old,” he says. “These are cases that are perfect for cross-linking because we’re seeing the patients when they’re just starting to show signs of the disease. I think if we fast-forward 10 or 20 years after cross-linking, we’ll find that these individuals in their 30s and 40s are still maintaining stable topography and very good uncorrected or best corrected visual acuity, compared to what we’ve seen in patients who weren’t treated early. I’ve examined patients I treated six or seven years earlier when they were in their teens, and they’re still doing extremely well.”

A. John Kanellopoulos, MD, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU Medical School in New York City and medical director of the Laservision.gr Institute in Athens, Greece, agrees that waiting for proof of progression can be counterproductive in young patients. “Cross-linking is globally acceptable for patients under 25 years old who have symptoms of visual change and keratoconus,” he says. “Most surgeons experienced with cross-linking would offer it as a means of stabilizing these corneas, even in the absence of enough followup to prove progression. In younger patients, keratoconus can progress rapidly, and the opportunity to address this and avoid a possible future transplant may be critical.”

|

| Corneal collagen cross-linking is showing potential far beyond simply mitigating the progression of keratoconus and ectasia. |

William B. Trattler, MD, director of cornea at the Center for Excellence in Eye Care in Miami, agrees. (Dr. Trattler has been involved with corneal cross-linking since participating in the 2008 FDA clinical trial, and has done extensive work with Dr. Rubinfeld, Doyle Stulting, MD, and other surgeons on developing an effective epi-on cross-linking protocol as part of CXLUSA.) “Keratoconus is a progressive disease, and our experience is that children with keratoconus are likely to progress more quickly than adults,” he says. “When a child or teenager develops keratoconus, the general recommendation is to consider treatment with cross-linking at that time rather than wait for progression. I have one 10-year-old patient whose mom wanted her son to wait for spring break to undergo the cross-linking procedure. The family waited three months. During this time, the child’s corneal shape and vision declined. If the patient had undergone cross-linking within a few weeks, progression could have been avoided.

“Fortunately,” he adds, “not all young patients have rapid progression. But since it can be difficult to determine which young patients are most likely to progress rapidly, it’s helpful to provide cross-linking shortly after diagnosis rather than waiting to document progression.”

Treating Older Patients

Although the FDA didn’t place any upper age limit on treatment, older individuals are less likely to progress, making their treatment off-label. So, deciding whether to treat—and whether to wait for proof of progression—is a somewhat different problem when the patient is older.

“As the patient’s age at the time of the initial encounter increases—for instance, when treating a patient age 25 to 35—evidence of progression is probably prudent prior to performing cross-linking,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “In general, patients over 40 are rarely found to progress, but we should never exclude that possibility. We recently encountered a patient in his 60s who, after many decades of a stable cone and without any specific explanation such as a recent increase in eye-rubbing, had increased progressive ectasia and had to be cross-linked.”

“We do have some elderly keratoconus patients,” says Dr. Majmudar. “Most of the time, patients who have keratoconus or ectatic disorders are going to slow down and stabilize by their mid 40s or so—although pellucid marginal degeneration may have a little bit longer time horizon.” Dr. Majmudar says he doesn’t put much stock in the idea of looking for proof of progression in older patients. “I don’t think that has any scientific merit,” he says. “The technology is so safe and effective—especially when you’re talking about epi-on technology—that we haven’t had a single complication in more than 2,500 cases. I don’t see any downside to doing it.

“However,” he continues, “there’s an out-of-pocket cost to the patient because insurance probably won’t cover it. That’s problematic, because if I’m asking someone to pay out-ofpocket, I want some sort of reassurance that they’ll see a clinically significant benefit. If an older patient hasn’t progressed in 10 years, I’m not going to ask him to spend money on a procedure that may or may not do anything for him. So in that situation, we suggest waiting. Even if there is progression, it will occur slowly.”

However, preventing progression isn’t the only consideration. Dr. Trattler points out that the idea that crosslinking only stabilizes the cornea is a misconception. “The cross-linking procedure also reshapes the cornea over time,” he explains. “The cornea will gradually become flatter, as happened in the FDA clinical trial, and best-corrected vision can potentially improve as a result.

“For example, consider a 65-yearold patient with keratoconus who can achieve 20/20 with scleral contact lenses, but his best visual acuity with spectacles is 20/50,” he says. “Even though progression is uncommon in patients in their 60s, it can occur, and the cross-linking procedure will prevent that. More importantly, he could improve from a BCVA of 20/50 to 20/30 over two or three years.”

|

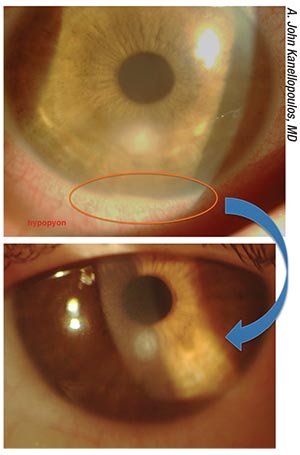

| A case of infectious keratitis in a 38-year- old female, post-RK. A customized, variable- fluence, variable-pattern cross-linking treatment helped to address the infection. |

|

In fact, Dr. Majmudar says his practice sees a few older patients who just want to have cross-linking to see if it might have a positive effect on their topography. “We have seen improvements in a certain segment of the population at that age,” he notes. “They may not have been progressing, but after cross-linking, six months or a year later we see some corneal flattening and improvement in vision. It seems reasonable to us to do this and stabilize their corneas because they’re likely to have other surgeries such as cataract surgery in the future. So we haven’t limited ourselves to patients in a certain age range.”

Cross-linking with LASIK

One promising possibility for crosslinking is combining it with refractive procedures such as LASIK and PRK, potentially stabilizing the altered cornea and possibly offsetting any corneal weakness induced by cutting a flap.

Dr. Kanellopoulos says that his group has demonstrated that the use of cross-linking along with refractive procedures such as LASIK and PRK can be beneficial. “We’ve shown that cross-linking works synergistically with a partial topography-guided PRK normalization in keratoconus patients, using the Athens Protocol,” he says.1,2 “This approach has become the standard of care globally. In addition, the use of cross-linking along with LASIK may be viewed as a means to offset the reduction in biomechanical stability of the cornea caused by LASIK.”3-5

Some surgeons, however, are skeptical of combining cross-linking with LASIK. “In the international space there’s been discussion about a procedure called ‘LASIK Xtra,’ where the surgeon performs LASIK on a patient who may have a higher risk for ectasia,” notes Dr. Majmudar. “At the time of the LASIK procedure, the surgeon applies riboflavin to the stromal bed, replaces the flap, and then performs UVA light application to complete the cross-linking process. To me, this doesn’t seem like a great idea. If you have a patient who may be at risk for developing ectasia, I’m not sure I’d recommend doing LASIK in the first place. I’d do PRK instead. In fact, combining PRK with crosslinking may make more sense in some of these situations.

“Of course, if a post-LASIK patient has developed ectasia, treating it with cross-linking is appropriate— we’ve been able to demonstrate very successful outcomes, comparable to those seen in keratoconus patients,” he adds. “But as a routine procedure on a new patient who’s never had LASIK before, I don’t think performing LASIK and cross-linking at the same time makes sense.”

Dr. Trattler reports that he also is not a fan of combining LASIK and cross-linking. “If a patient is interested in undergoing laser vision correction, and during the preoperative evaluation keratoconus is identified, that patient should undergo cross-linking, not LASIK or PRK,” he says. “If the patient is found to have mild keratoconus and has good BCVA and a low refractive error, the patient can consider PRK. It’s simpler than a combination procedure. Simpler is often better, and PRK can provide very good visual outcomes.”

Dr. Kanellopoulos agrees that questions about combining LASIK and cross-linking remain. “Those questions include: Which eyes require this? And, should this approach be used in LASIK cases that are considered high-risk, such as high myopes or lower-age patients?” he says. “Of course, this should not be taken as an endorsement of performing LASIK in corneas that are suspicious for ectasia, such as forme fruste keratoconus.”

Cross-linking with PRK

Combining cross-linking with PRK is becoming popular outside the United States, especially when the PRK is topography-guided. “There’s still a very large segment of the keratoconus population that has been left with a fairly irregular cornea which results in some refractive morbidity,” says Dr. Majmudar. “They can’t see well without a rigid or scleral contact lens. I think the next phase of treatment will be to take these irregular corneas and make them more regular by doing topography-guided PRK and combining that with cross-linking. This will allow patients to be less dependent on customized rigid lenses.

“I’d like to explore what’s already being done internationally—a protocol that combines topography-guided PRK and cross-linking, so we can treat patients who have these irregularities and rehabilitate them—not just try to prevent them from getting worse,” he says. “Most of the patients who have keratoconus are fed up and miserable with their contacts. Rehabilitating these patients is the holy grail in the field of keratoconus treatment.”

Dr. Majmudar notes that this could also help individuals who are early in the disease and hoping to get refractive surgery. “When one of these patients comes in and you’re not sure that operating on that eye is a good idea, topography-guided PRK combined with cross-linking to stabilize it might be a good solution,” he says. “These are patients who have funnylooking corneas—maybe not frank keratoconus, perhaps forme fruste keratoconus—but have pretty good visual acuity with glasses or contacts. We should be able to help them, either with a standard PRK plus crosslinking, or a topography-guided PRK if they have already developed some irregularity. That’s where we’re going to try to find a synergy between these two modalities.”

| Cross-linking for Post-RK Diurnal Fluctuation? |

| Parag A. Majmudar, MD, president and chief medical officer of Chicago Cornea Con- sultants, says he has tried using cross-linking for post-RK diurnal fluctuation, although only in a handful of cases. “That’s not enough to draw a meaningful conclusion,” he admits. “Nevertheless, we thought cross-linking might be effective for this purpose, but my sense is that it doesn’t work the way we’d like—the way it does for keratoconus or post-LASIK ectasia. There’s something in the mechanism of post-RK diurnal fluctuation that doesn’t lend itself to being limited by the cross-linking process. “Others in our group have done a more extensive evaluation of this,” he adds. “Their conclusion is the same—that we can’t get a reproducible effect on post-RK corneas at this time.” |

Dr. Kanellopoulos says his group has reported extensively on this type of work. “Last year at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting we introduced 10-year data on combining customized, topographyguided partial PRK with cross-linking using the Athens protocol in eyes with ectasias and keratoconus,” he says. “This was a means to not only stabilize corneal ectasia, but also dramatically improve visual function.”

Dr. Trattler, however, says he’s not a big fan of performing PRK and crosslinking simultaneously. “There’s an increased risk of corneal haze as well as other complications,” he points out. “For my keratoconus patients, I feel the more effective option is to perform cross-linking as a primary procedure. Over the next one to four years the corneal shape will improve. Then, at some point during the postoperative course, the patient may become a candidate for PRK to potentially further improve his vision and reduce the need for contact lenses or glasses.

“These are typically patients who start off with less-severe keratoconus,” he notes. “For patients with more advanced keratoconus, the advantage of performing cross-linking first is that the corneal shape can improve, and the cornea will have become stronger. Patients can then become candidates for topography-guided PRK. Of course, if there are any signs of keratoconus recurrence after PRK, they’ll need to undergo a second crosslinking procedure.

“When cross-linking is performed first, I recommend waiting six months to four or five years before performing PRK,” he adds. “The longer the time frame, the greater the improvement in corneal shape. In some cases of mild keratoconus with a low refractive error and BCVA of 20/25 or better, rather than combining PRK and crosslinking, surgeons can perform PRK alone for refractive purposes and then observe patients on an annual basis during the postoperative period. If ectasia were to develop, the cross-linking could be performed at that time. Fortunately, in patients with mild keratoconus and low levels of myopia, the risk of ectasia after PRK is low.”

Treating Corneal Infections

Dr. Kanellopoulos notes that there have been several studies reporting that the use of corneal cross-linking can be effective for treating bacterial infections.6-8 “Obviously, the use of antibiotics is still considered standard of care,” he says. “However, cross-linking may help, in a bimodal way. First, it may reduce the occurrence of corneal melt and the spread of the infection within the corneal stroma by increasing the cornea’s rigidity. Second, it appears to have a direct bactericidal effect. It remains to be determined whether cross-linking will change the bioavailability of topical or oral antibiotics within these corneas, which could impact their efficacy, but the preliminary data shows that cross-linking can be an effective means to address some types of corneal infection.

“Along those lines, we recently submitted a report of a study in which we used customized, variable-fluence and variable-pattern cross-linking to pinpoint and topographically guide a spot of cross-linking on the infiltrate,” he says. “This approach was relatively successful at reducing the infiltrate size. Of course, this was done along with the use of topical antibiotics.”

Dr. Trattler reports that he has had some limited personal experience with treating corneal infections with crosslinking. “We treated one patient who had fungal endophthalmitis and developed a full-thickness fungal corneal infection,” he says. “The cross-linking treatment didn’t work, which was most likely due to the fact that the crosslinking therapy couldn’t reach the deeper portions of the cornea.”

Dr. Majmudar says that he hasn’t tried using cross-linking to treat problems such as fungal or bacterial postinfectious keratitis, but he believes it may have value. “The main issue is that when you have an organism like a bacteria or fungus, collagenases—enzymes that break down collagen—are part of the defense mechanism your body uses to try to eradicate the organism,” he explains. “Unfortunately, collagenases can destroy normal corneal tissue as well. However, if the cornea has been strengthened using crosslinking, that might help to minimize the damage to the cornea itself. It’s also possible that the UV light itself may have a sterilizing effect. There’s definitely enough there to warrant further investigation.”

Combining CXL with Intacs

Dr. Majmudar says that combining cross-linking with Intacs has been a useful option. “I’ve done a fair amount of that,” he says. “Most of the time, we find that cross-linking gives us a significant amount of corneal flattening, but there are patients who still have to wear contacts, and they’re still unhappy. In the past, when we didn’t have the option of topography-guided PRK, all we had to help them was Intacs. Typically, my protocol was to wait about six months after cross-linking and then perform Intacs to see what additional impact we could have.

“The issue with Intacs has been that there’s a fair amount of variability in terms of the effect we get,” he continues. “In the United States we’re also limited in terms of what sizes of rings are available. For the longest time, we only had two ring thicknesses. The larger, 0.45-mm ring, did give us a little bit more flattening, but the results were still more variable than what we were seeing in other countries that had access to more ring options.

“As a result, we tended to favor sequential treatment rather than doing Intacs and cross-linking simultaneously,” he says. “Even so, we still had a fair amount of variability in our results, so it kind of fell out of favor in our practice. Perhaps the most significant factor was problems with reimbursement. Insurance companies rarely reimbursed us for the Intacs; a lot of times it was out of pocket for the patient. Since the results were not reproducible, it was hard for us to ask patients to pay for the procedure.”

Dr. Trattler says he’s aware of keratoconus patients who have undergone cross-linking combined with Intacs. “My understanding is that surgeons create the Intacs channels, and then inject riboflavin solution into the channels so the riboflavin can spread within the cornea,” he says. “Following treatment with the UV light, the Intacs segments can be placed.” Dr. Trattler notes that this can have another benefit. “At centers where effective epi-on riboflavin solutions are not available, using the Intacs channels for riboflavin placement can allow for an epi-on procedure,” he says. “That has a lower risk profile than epi-off cross-linking.”

CXL for Refractive Correction

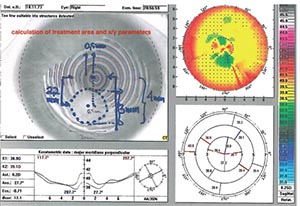

Other applications that are showing promise include the use of customized, variable-pattern, variable-fluence cross-linking to address refractive error, based on topography. “This is called refractive cross-linking,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “This includes the concept of treating corneal irregularity with a higher refractive correction than standard cross-linking.

“We reported the first clinical experience with this back in 2013,9,10 but it has yet to become mainstream,” he notes. “That’s partly because other options such as using a laser to treat refractive error are more time-proven. In the future, however, I wouldn’t be surprised to see cross-linking used as a means to modulate corneal biomechanics and generate slight refractive corrections. By then, the efficacy and safety track record of this type of procedure will be established.”

Dr. Majmudar says while he finds the idea of using cross-linking to produce a refractive correction plausible, he’s skeptical that it will work well. “I’m not sure you can tailor it precisely enough to get the exact effect you need to correct a refractive error,” he says. “Furthermore, how long will the change last? And is it reproducible? These are questions that need to be answered.”

Dr. Majmudar also points out that corneal changes associated with crosslinking that impact refraction are not the same from patient to patient. “I’ve seen some keratoconus corneas flatten quite a bit after treatment, but I’ve also had patients with mild keratoconus who had virtually no flattening, at least with our type of cross-linking,” he says. “In our experience, the higher the degree of irregularity in keratoconus, the more flattening we see. Of course, these treatments did not involve focal cross-linking, directed at a specific part of the cornea, and it’s possible that changing the parameters might cause a greater effect. But I still believe that most ‘normal’ corneas are not going to get a significant refractive shift—certainly not more than 2 or 3 D at the most. So I doubt that it will replace a procedure like LASIK. I don’t think it’s precise enough to rely on, even in a keratoconus patient—at least not today.”

It’s Still Early in the Game

It’s clear that corneal cross-linking is likely to end up being used in a number of ways. However, it’s still early in the game, and much more research needs to be done. Not only do we need to know more about how to perform some of these procedures effectively, we need to know more about the cornea and how its characteristics make cross-linking useful—or a waste of time.

Dr. Kanellopoulos agrees. “A key piece of information needed to justify using cross-linking in a broader number of patients is missing,” he says. “Until we have a metric to measure corneal biomechanical properties and what the threshold is for eyes to develop ectasia, we’ll probably treat more corneas than actually need the treatment. We still don’t really know which corneas require cross-linking prophylactically.”

Dr. Trattler has a financial interest in Avedro and CXL Ophthalmics. Dr. Kanellopoulos is a consultant for Avedro and Alcon. Dr. Majmudar is an investor in CXLO.

1. Kanellopoulos AJ. Comparison of sequential vs. same-day simultaneous collagen cross-linking and topography-guided PRK for treatment of keratoconus. J Refract Surg 2009;25:9:S812-8.

2. Kanellopoulos AJ, Asimellis G. Corneal refractive power and symmetry changes following normalization of ectasias treated with partial topography-guided PTK combined with higher-fluence CXL (the Athens Protocol). J Refract Surg 2014;30:5:342-6.

3. Kanellopoulos AJ, Asimellis G, Karabatsas C. Comparison of prophylactic higher fluence corneal cross-linking to control, in myopic LASIK, one year results. Clin Ophthalmol 2014;8:2373-81.

4. Kanellopoulos AJ, Kontos MA, Chen S, Asimellis G. Corneal collagen cross-linking combined with simulation of femtosecond laser-assisted refractive lens extraction: An ex vivo biomechanical effect evaluation. Cornea 2015;34:5:550-6.

5. Kanellopoulos AJ, Asimellis G, Salvador-Culla B, Chodosh J, Ciolino JB. High-irradiance CXL combined with myopic LASIK: Flap and residual stroma biomechanical properties studied ex-vivo. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:6:870-4.

6. Müller L, Thiel MA, Kipfer-Kauer AI, Kaufmann C. Corneal cross-linking as supplementary treatment option in melting keratitis: A case series. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2012;229:4:411-5.

7. Makdoumi K, Mortensen J, Crafoord S. Infectious keratitis treated with corneal crosslinking. Cornea 2010;29:12:1353-8.

8. Zloto O, Barequet IS, Weissman A, et al. Does PACK-CXL change the prognosis of resistant infectious keratitis? J Refrac Surg 2018;34:8:559-563. 9.KanellopoulosAJ,DuppsWJ,SevenI,AsimellisG.Torictopographically customizedtransepithelial, pulsed, very high-fluence, higher energy and higher riboflavin concentration collagen cross-linking in keratoconus. Case Rep Ophthalmol 2014;5:2:172-80.

10. Kanellopoulos AJ, Asimellis G. Hyperopic correction: Clinical validation with epithelium-on and epithelium-off protocols, using variable fluence and topographically customized collagen corneal crosslinking. Clin Ophthalmol 2014;8:2425-33.