|

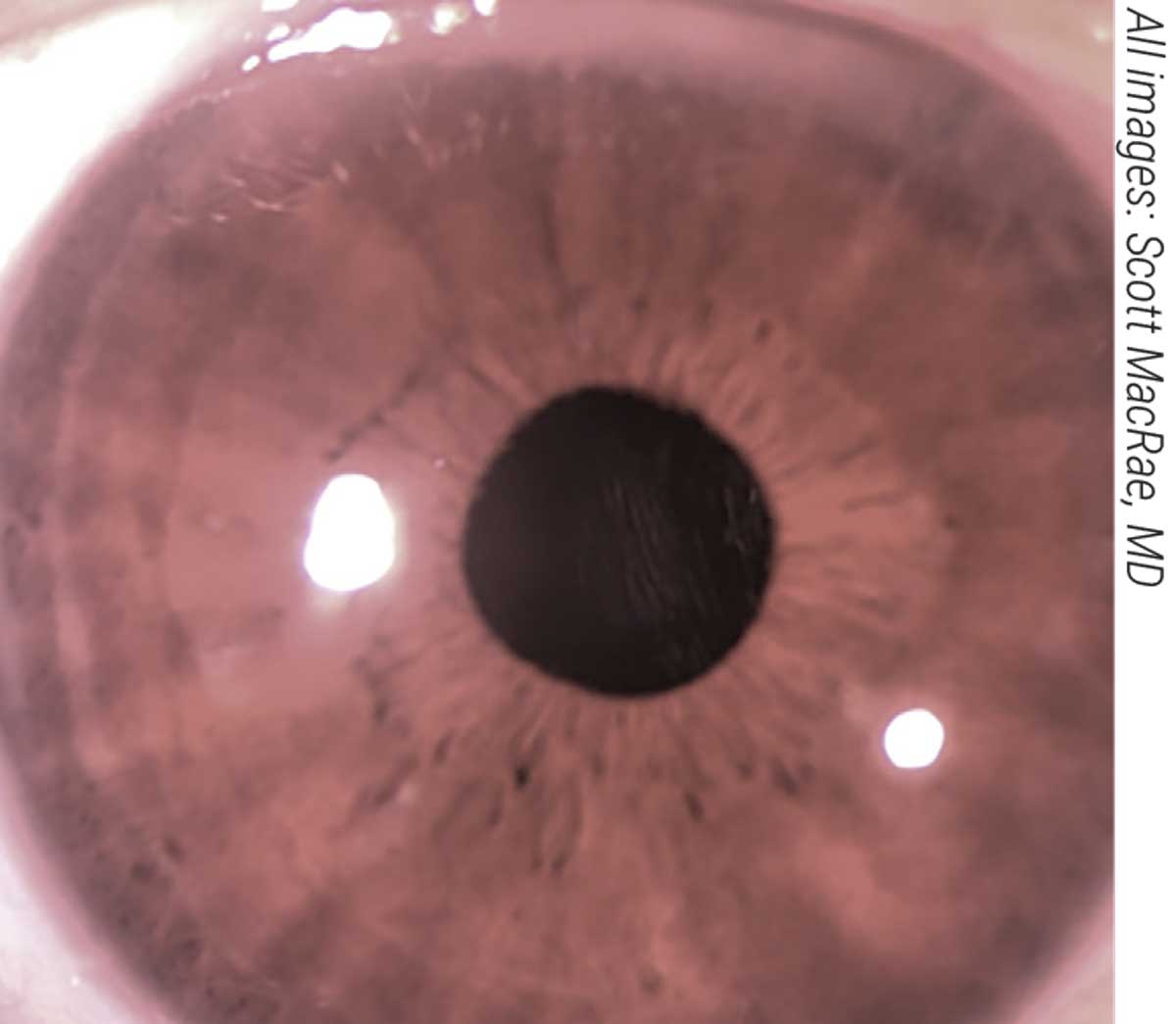

| Figure 1A. A LIRIC-treated eye one day postop. Patients typically recover in 24 hours due to the non-invasive and non-ablative nature of LIRIC. |

After almost two decades in the works at the University of Rochester, a new vision-correction technology called LIRIC, or laser-induced refractive index change, was successfully used in its first in-human trial to correct refractive error non-invasively.1 The procedure operates at pulse energies much lower than what’s currently used in femto-LASIK, making it a fundamentally safer procedure, according to LIRIC pioneer Scott MacRae, MD, chief of the Cornea and Refractive Surgery Service and a professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the Flaum Eye Institute, University of Rochester.

Here, Dr. MacRae explains how this new technology works, and shares some results of the trial.

Stromal Modification

LIRIC uses pulse energies 100 to 1,000 times lower than the flap-cutting regime. “Without tissue ablation, there’s no incision, less keratocyte cell death and less nerve death in the cornea,” Dr. MacRae explains.

“The corneal stroma can be thought of as a mixture of constituent ingredients, namely collagen and water,” he says. “Collagen (dehydrated) has an index of refraction of about 1.5; water is 1.33. In a healthy cornea, water content is finely controlled by the endothelial pump and proteoglycans of the stroma, resulting in a stromal index of roughly 1.38. LIRIC’s mechanism is based on modifying this mixture of collagen and water within a micrometer-sized region of action.

“Within the focal spot of the femtosecond laser, the collagen matrix is modified, and the collagen fibrils are more densely packed, leading to a change in the refractive index,” he continues. “The magnitude of LIRIC is proportional to the pulse energy (again, below the damage threshold) and the spot is scanned across the optical zone. Thus, a variety of optical wavefronts can be inscribed within the cornea (e.g., sphere, cylinder, higher-order aberrations, multifocal, etc.).”

Dr. MacRae says LIRIC’s greatest advantage is its non-invasive nature. By avoiding ablation, LIRIC preserves the cornea’s original curvature and avoids epithelial remodeling and the subsequent regression seen in the early days of laser refractive surgery, he points out.

“The lower pulse energies have also been shown, histologically, to preserve the stromal nerves (unlike laser refractive surgery),” he notes. “We expect this will reduce the rates of postop dry eye, but this remains to be seen. Also, LIRIC doesn’t remove tissue, obviating the concern about corneal ectasia. Subjectively, this incision-free procedure may attract patients for whom ‘fear of surgery’ is a major obstacle to getting laser vision correction. Incisionless vision correction also may have implications for in-office procedures and applicability to the developing world.”

|

| These IOP measurements made by a patient before and after a repeat selective laser trabeculoplasty treatment illustrate a key advantage of multiple daily measurements. If in-office measurements had been taken at the time point shown by the arrows, a clinician might have concluded that the treatment didn’t lower the pressure significantly. However, with multiple home measurements, the mean pressure was shown to have dropped from 22.8 mmHg pre-treatment to 18.5 mmHg post-treatment, a 19-percent reduction. |

The Procedure

The LIRIC platform can correct sphere, cylinder, higher-order aberrations and even presbyopia using multifocal patterns. Dr. MacRae says that good candidates include those who are unable to undergo LASIK due to a thin cornea and those who fear invasive surgery.

“We’re also developing LIRIC for use as a postop touch-up in intraocular lenses and contact lenses,” he says. “The IOL touch-up is important for post-surgery residual refractive error. Contact lenses are exciting because we can offer popular diffractive multifocal patterns that are successful for cataract patients in the form of a contact lens for phakic presbyopes.”

He says that patients recover from LIRIC in about 24 hours. Additionally, since the corneal epithelium and stroma aren’t significantly disrupted, the patient doesn’t need to take topical antibiotics or steroids for the typical five to seven days, as in the current regimen with corneal refractive surgery.

Currently, the cornea procedure takes just under 90 seconds, but Dr. MacRae says the goal is much shorter. “We’re refining our laser system to meet a goal of less than 20 seconds per procedure,” he says. “For perspective, the first LIRIC contact lenses we produced took more than 10 hours to write in hydrogel materials. These first lenses were so-called ‘hero experiments’ run by graduate students at the University of Rochester.”

Dr. MacRae adds that because LIRIC is less disruptive and doesn’t thin the cornea, it has the potential to be used for repeat treatments if a patient’s refractive error changes or the patient later develops presbyopia. “We’ve done repeated treatments in animals, but this needs to be validated in human studies,” he says.

How easily will refractive surgeons be able to adopt and offer LIRIC in the future? “LIRIC certainly requires a laser system specialized for modifying refractive index,” Dr. MacRae says. “At the moment, the LIRIC device is a stand-alone system (Clerio Vision). In the future, we may pursue coupling the LIRIC system with a flap-cutter to reduce the footprint in the OR, but that’s yet to be determined.”

Establishing Safety

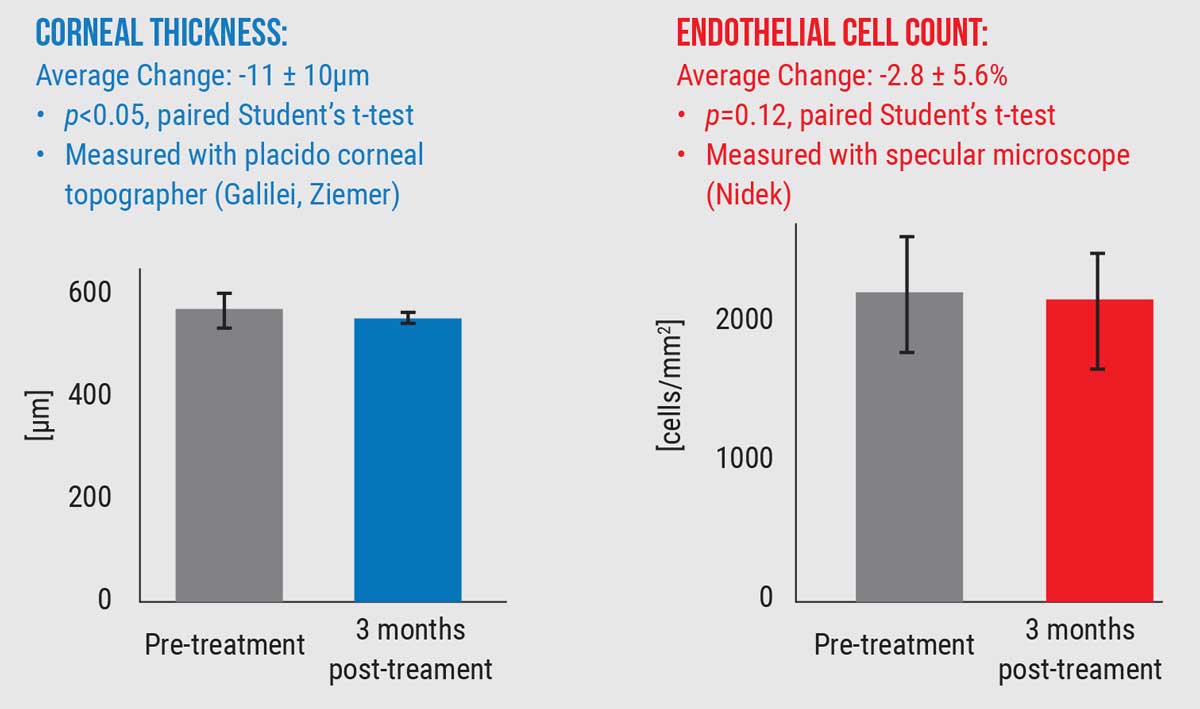

The first in-human trial established the safety profile of LIRIC when performed using a blue, 405-nm wavelength laser system. “All 27 patients showed excellent safety outcomes,” Dr. MacRae says. “No eyes exhibited inflammation or a wound-healing response. All corneas were clear post-treatment and there were no signs of haze, scarring, endothelial damage or opacity.

|

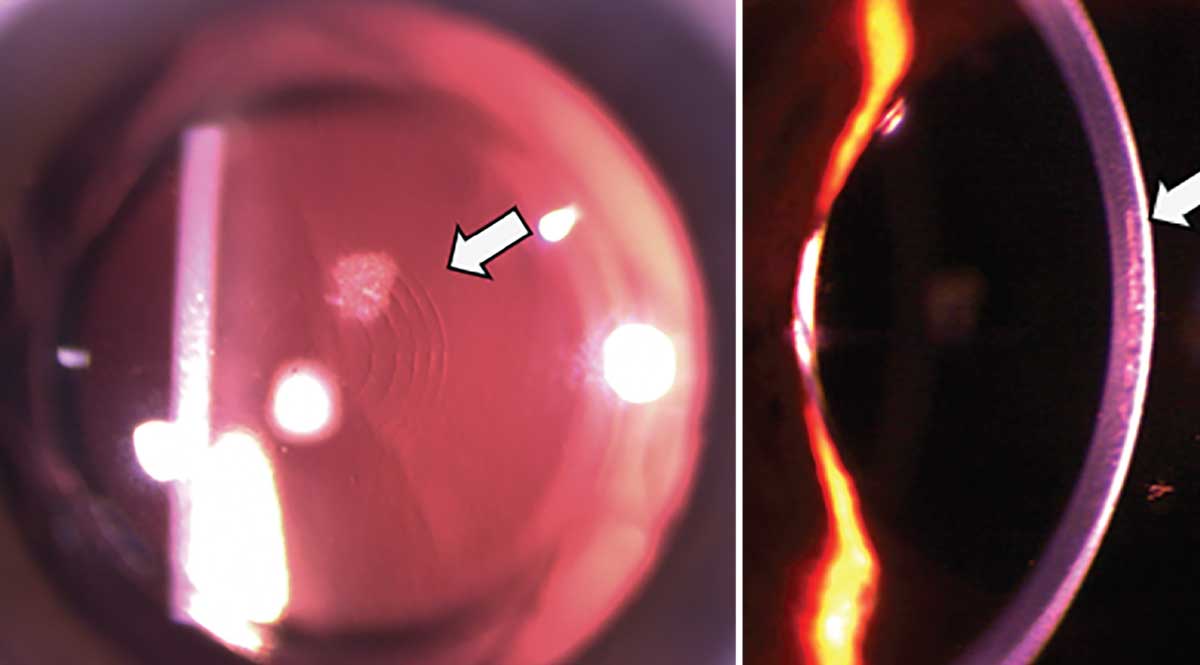

| Figure 1. One week after LIRIC treatment. In the first in-human trial, patients had clear corneas, no light scatter and no evidence of scarring or opacity immediately after treatment or up to three months post-treatment. |

“We were very pleased with these outcomes,” he says. “However, since before this we had only tested the procedure in anesthetized animal models, we weren’t sure what to expect regarding the patient’s reaction to the treatment. For example, would the laser be ‘too bright’? However, it turned out that the flat-applanation patient interface caused patients’ vision to fade after about five seconds with applanation, similar to flat-applanation for cutting a LASIK flap. This made the treatment virtually invisible.”

A Paradigm Shift in Refractive Surgery?“A non-incisional and non-ablative refractive surgical procedure would represent a paradigm shift in how we perform refractive surgery,” notes Edward Manche, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and director of the Cornea and Refractive Surgery Service at Stanford University. “Of course … it would need to achieve outcomes at least as good as what we can achieve with our current state-of-the-art LASIK, PRK and SMILE surgical procedures.”He says such a non-ablative refractive procedure would have a number of significant advantages over current ablative procedures. “There would be little or no concern with regards to biomechanical weakening of the cornea and little or no risk of infectious keratitis or non-healing epithelial defects,” he says. “It could also be useful in very thin corneas and corneas with borderline corneal topographies. Additionally, the prospect of potentially minimizing postop dry eye, due to little or no effect on the corneal nerve plexus, is also appealing. “LIRIC may prove to be especially useful in addressing residual refractive errors after cataract surgery,” he continues. “The LIRIC treatment could be performed on either the IOL or the cornea depending on the effectiveness of the different technologies. This would dramatically improve outcomes with cataract surgery anwould also offer patients the ability to have multifocality on their IOL or cornea to reduce or eliminate the need for near-vision glasses after cataract surgery.” He says safety is the most important issue to study when considering a novel technology. “There have been animal studies as well as studies in humans that assessed the safety of the procedure,” he says. “Based on the preliminary data presented at meetings, it appears that the procedure is safe. However, larger, longer-term, prospective, multicenter clinical trials are needed to establish the safety, efficacy, predictability and stability of the procedure before it can be widely adopted. “LIRIC has the potential to displace LASIK, PRK and SMILE surgery as the dominant refractive surgical procedure,” he says. “In order to do so, LIRIC would have to have the same or superior safety, efficacy, predictability and long-term stability that’s seen with our current state-of-the-art keratorefractive surgeries. In the near term, it may be initially used to induce multifocality in the cornea or IOL to treat presbyopic and/or pseudophakic patients.” —CL |

So far, in vivo animal experiments have demonstrated that LIRIC treatment persists in the cornea for up to two years post-treatment (the longest animals have been tracked to date).2-4 Ongoing research and clinical studies are being conducted to demonstrate the same in humans.

As for long-term consequences, Dr. MacRae says, “We have no reason to expect that altering the cornea’s refractive index will have any negative effects down the line. LIRIC operates at pulse energies much lower than what’s currently used in femto-LASIK, so it’s fundamentally a safer procedure. We’ve also found that LIRIC has had no detrimental effect on endothelial cell count, which is further evidence of safety.”

LIRIC’s Future

Dr. MacRae says that in addition to reducing the treatment time to under 20 seconds, they’re still investigating the best laser paradigm to use. “For example, there’s already ample precedent for using near-infrared femtosecond lasers for ablation (e.g., corneal flaps, SMILE, etc.); therefore, LIRIC may have broader acceptance if it’s performed with a more familiar laser wavelength. However, the physics of multiphoton absorption dictates that the longer the wavelength, the more challenging it is to produce the desired effect. More research is required before we finalize our decision on a wavelength and laser settings.”

Dr. Colvard is a surgeon at the Colvard-Kandavel Eye Center in Los Angeles and a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. Dr. Charles is the founder of the Charles Retina Institute in Germantown, Tennessee.

Dr. MacRae is a paid consultant to Clerio Vision, the company developing LIRIC.

Dr. Manche has no financial disclosures related to LIRIC. He owns equity in RxSight, VacuSite and Placid0 and is a consultant to Avedro and Johnson & Johnson Surgical. He also conducts sponsored research for Allergan, Alcon, Avedro, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Novartis and Presbia.

1. Zheleznyak L, et al. First-in-human laser-induced refractive index change (LIRIC) treatment of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019;60:9:5079-5079.

2. Savage DE, et al. First demonstration of ocular refractive change using blue-IRIS in live cats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:7:4603-12.

3. Wozniak KT, et al. Temporal evolution of the biological response to laser-induced refractive index change (LIRIC) in rabbit corneas. Exp Eye Res 2021;207:108579.

4. Brooks DR, et al. Measurement and design of refractive corrections using ultrafast laser-induced intra-tissue refractive index shaping in live cats. Ophthal Tech 2018;28:10474.