Treating patients complaining of dry eye used to be a less-than-satisfying part of an ophthalmologist’s job; the problem wasn’t well understood and treatment options were limited. Today, that has changed dramatically. “Dry eye” is now understood to be a complex issue with multiple etiologies, and treatment options for the different aspects of the disease are proliferating. But as the field has expanded, the difficulty of staying on top of the latest developments has also increased.

Here, experts share the latest thinking about the group of concerns commonly labeled “dry eye” and offer advice for helping these patients achieve true, long-lasting relief.

Spotlight: Meibomian Glands

“In the old days, treating dry eye was just about supplementing inadequate tears using over-the-counter artificial tears,” recalls Esen Akpek, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and director of the Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic at the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore. “Then came the idea of treating inflammation to improve the quantity and quality of tears; that approach became popular with the approval of Restasis.

“In the past five years, the focus has shifted again,” she says. “Now we’re much more aware of meibomian gland problems, and we know that pure aqueous tear deficiency is a lot less common than meibomian gland dysfunction. In fact, meibomian gland dysfunction and aqueous tear deficiency occur together in more than 80 percent of patients. The problem usually starts as meibomian gland dysfunction; over a period of decades, that causes an aqueous tear deficiency as well.

“Today we know that each component needs to be addressed separately,” she adds. “As a result of this, we’re trying to come up with better ways to diagnose meibomian gland dysfunction, and we now have better ideas about how to address the problem. Indeed, the majority of new dry-eye treatments are focused on addressing meibomian gland dysfunction.”

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, director of the cornea service at Wills Eye Hospital and a professor of ophthalmology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, agrees. “I think about 80 percent of patients with ocular surface disease have a component of meibomian gland dysfunction that should be treated,” he says. “Ignoring the meibomian gland problem—if it’s there—is bad for patients and doctors.”

Mark Milner, MD, FACS, an associate clinical professor at Yale University School of Medicine, notes that doctors have always been aware of meibomian gland dysfunction. “However, it was underdiagnosed for years,” he says. “No treatments were approved for blepharitis, and getting insurance to pay for compounded or non-approved treatments was always difficult.

“Today we have more ways to diagnose it, with devices that can image the meibomian glands and thermal pulsation devices like LipiFlow, iLux, TearCare and eyeXpress that heat the lids and help you express the glands,” he says. “As a result, we’re starting to embrace this problem.”

Dr. Akpek points out that meibomian gland dysfunction is actually an age-related problem. “It’s like wear and tear on your teeth as you grow older,” she says. “If you don’t take care of your teeth, you develop dental plaques and caries. Eventually, you lose your teeth and need dentures. The same thing is true with the meibomian glands; if you don’t care for them, they stop functioning correctly and symptoms of dry eye develop. Eventually the glands undergo permanent atrophy. So patients need to be caring for their meibomian glands on a regular basis.

“This idea of proactively taking care of your eyes is kind of new,” she notes. “In fact, patients should ideally have home treatment modalities that keep the meibomian glands in good shape; they shouldn’t have to come to the office for frequent treatments. Hopefully, these home treatments will end up being more impactful than just doing hot compresses with a rag.”

Addressing Inflammation

Approved treatments such as Restasis and Xiidra have raised awareness of the importance of treating inflammation when managing dry eye, but many ophthalmologists have reported that their dry-eye patients don’t always seem to get relief from these drops.

|

Dr. Milner says he believes that this is partly because of a misconception about the nature of dry-eye disease. “Like glaucoma, dry eye often requires more than one treatment to resolve the problem,” he says. “If a glaucoma patient has a pressure of 27 mmHg and needs to be at 17, one drop might only take him down to 22 mmHg.

In that case, you wouldn’t stop the drop; you’d add another drop.

“In contrast, I think most doctors expect these anti-inflammatory dry-eye drops to be a panacea,” he continues. “If you use Restasis or Xiidra and the patient is 50 percent better, the problem isn’t that the drops aren’t working, it’s that the patient needs more than one treatment. You might need to add punctal plugs, and maybe Azasite for the blepharitis, and maybe doxycycline for the meibomian gland dysfunction.

“About 85 percent of my patients have some success with Restasis and Xiidra,” he says. “That means anything from mild success to ‘This is a miracle drug.’ The other 10 to 15 percent will say either that they didn’t improve, or that the side effects such as burning were so bad that they couldn’t tolerate it. We try to get around the burning problem by having the patient refrigerate the drops and/or use an artificial tear 10 minutes before and after. We educate them about the burning, and we may use a steroid off-label. Even so, the burning is still too much for some patients, so they stop.”

In terms of adding other treatments, Dr. Milner says the CEDARS algorithm can be helpful. (To learn more about the CEDARS algorithm, check out “Three New Algorithms for Treating Dry Eye” in the October 2017 issue of Review.) “Let’s say you start your patients on Restasis or Xiidra and they come back 40 percent better,” he says. “If Schirmer’s is still low, you can plug them. If their meibomian glands are still inflamed, you can do a LipiFlow, or Azasite off-label, or oral doxycycline. If Schirmer’s is OK but there’s still an evaporative problem, you might need an over-the-counter vitamin A ointment, used off-label, which may improve goblet cell health.

“The reality is, many patients need two or three different treatments,” he concludes. “When a doctor says a dry-eye treatment wasn’t successful, it probably was—it just didn’t solve the entire problem.”

Another question that arises regarding Restasis and Xiidra is whether they’re useful if the core of a patient’s dry-eye problem is meibomian gland dysfunction rather than aqueous deficiency. Dr. Milner says in his experience, Restasis and Xiidra do help to address meibomian gland dysfunction, although this use is off-label. “The inflammatory process in the meibomian glands is very similar to that in the lacrimal glands,” he notes. “T-cells and inflammatory cells are part of the meibomian gland disease process as well, and recent evidence suggests these drugs can help.1 But since this use is off-label, getting it covered by insurance has been difficult.”

Dr. Rapuano has used Restasis to treat meibomian gland dysfunction, and he agrees that it helps. “I don’t think it works as fast as when it’s used to treat aqueous deficiency,” he says. “It takes about three months to have a reasonable effect on aqueous deficiency, but it takes about six months for me to notice an improvement in meibomian gland dysfunction.”

Restasis Plus Xiidra?

Patients often ask Dr. Rapuano for assistance in deciding between a treatment course involving Restasis or Xiidra. “I say, ‘Restasis has been around for 14 or 15 years. It has a very good track record. It works a little bit more slowly, but it works very well. Xiidra’s the new kid on the block; it’s been around for a couple of years now. It tends to work a little faster, but it has a little taste issue and it can blur your vision. Both products work very well for most patients, but both of them can burn a little.’ I haven’t been as impressed with Xiidra for treating meibomian gland inflammation, but it seems to relieve dry-eye symptoms faster than Restasis,” he notes. “That’s the main thing going for it.”

Dr. Milner says that many dry-eye experts have noted that Restasis and Xiidra appear to be synergistic, although there’s no published data to support this claim. “The drugs work on different parts of the T-cell,” he says. “Many dry-eye specialists are now using them concurrently, the way you might use a steroid and a nonsteroidal together because they work on different parts of the inflammatory process. I have hundreds of patients who will tell you they got partial relief with one of the drops; then, when we added the other one, they got complete relief. Furthermore, if we then take them off one of the drops, they regress a little bit. So they appear to need both.

|

“We have those patients use both drops twice a day,” he adds. “I tell the patient to wait 10 or 15 minutes between the drops. If patients want to, they can alternate—Restasis in the morning and at dinner, Xiidra at lunch and bedtime. But most patients just do them twice a day separated by a few minutes.”

Dr. Milner concedes that this raises a practical concern: getting insurance to cover both drops. “Many patients aren’t on both,” he says, “not because the drugs wouldn’t work together, but because they can’t get coverage. Insurance companies have no problem paying for two or three glaucoma drops, but they won’t pay for two different dry-eye treatments. That shows a lack of understanding.

“We fight with the insurance companies, using information from our charts showing that these patients are doing better on both,” he adds. “But it’s a struggle. The insurance companies say they want to see a clinical trial showing the synergistic effect, and we don’t have that so far. But in my opinion, these drugs do work together to help patients, so we’re doing what we can to get both medications covered.”

Artificial Tears

Dr. Akpek says artificial tears are still relevant. “For milder episodic cases of dry eye, artificial tears are therapeutic,” she says. “They can even cure the problem, as long as the inciting factor has been eliminated. Unfortunately, by the time most patients come to see us, they don’t have a mild case. Patients have already tried over-the-counter drops. Some are using them every 10 minutes, which is wrong, because it disturbs the normal homeostasis of the tear film.”

“Artificial tears will always have a place,” agrees Dr. Milner. “Many new formulas are coming out, such as Allergan’s Refresh Optive Mega-3 tears, which may help with MGD. Freshkote isn’t new, but it’s now being re-marketed by Eyevance. The thing we like about Freshkote is that it’s preservative-free, so it’s usable with contacts.”

The presence of preservatives in many of the products is an issue. “Even if you try to direct patients to preservative-free drops, 99 percent of the time what they find and end up using isn’t preservative-free,” says Dr. Rapuano. “That can be a problem, because if they’re using preserved tears more than three or four times a day, the preservatives are probably causing some of the ocular surface disease. In that case, the drops won’t help as much as the patient wants, and they may make the problem worse.

“Patients with ocular surface issues should use preservative-free drops as much as possible,” he says. “Likewise, if the patient has ocular surface disease and is on multiple glaucoma medications—which many of our patients are—you should try to get that patient switched to less-toxic glaucoma medications, or, ideally, preservative-free glaucoma medications.”

Dr. Milner notes that many surgeons wonder why drops with preservatives should be recommended at all. “The ITF guidelines published in 2006 proposed recommending preserved tears for level-one disease, with nonpreserved tears for levels two to four,” he says.2 “When asked, the task force said that they included preserved tears in level one because artificial tears are a billion-dollar industry, and it’s unrealistic to expect people not to use preserved tears when they’re a big part of that market. So, we just restrict our recommendation to level-one disease.”

Devices for Treating MGD

Dr. Akpek says she has a low threshold for recommending an office-based meibomian gland procedure. “If a patient is already doing warm compresses, and I’ve tried a combination of omega-3 acids and oral antibiotics for two to three months and the patient isn’t getting better, then I’d definitely recommend one,” she says. “Of course there are different options, and the treatment should be tailored to the patient’s needs and the severity of meibomian gland dysfunction. We usually combine multiple treatments.

“Ironically, doctors often think that these modalities don’t work,” she notes. “That’s because they’re using them haphazardly. First of all, these are expensive instruments, so most people will just acquire one. Then they keep using the same treatment on every single patient, which is wrong. Do we use insulin on every single diabetic patient? No. We try different options, in a stepwise approach. That’s what we should be doing with these patients.

“The second reason these modalities may not always work is that we don’t have any guidelines to recommend which treatment should be done for which kind of finding, and how often they should be done, and what to do between treatments,” she continues. “Most dry-eye specialists do the same thing on every single person despite different needs, different skin types, different severity of meibomian gland dysfunction and different etiologies of meibomian gland dysfunction. Then the treatment fails and gets a bad reputation. It’s not that it doesn’t work—we’re just using it incorrectly.”

Dr. Rapuano says he uses LipiFlow on some of his patients. “LipiFlow is a safe and easy treatment, although it’s somewhat expensive and not covered by insurance,” he notes. “That’s why I put it pretty high up the treatment stepladder. However, if a patient asks about it, I explain how it works.

“It’s important to remember that it’s not a cure-all,” he continues. “It makes things better, but it’s not a substitute for hot compresses, ointments and other treatments. LipiFlow kick-starts the process by cleaning out the glands, but you have to keep them cleaned out or they’re just going to clog up again.”

Dr. Rapuano notes that the cost of LipiFlow has come down over the years. “When we first got LipiFlow about eight years ago, we charged about $1,800 for two eyes,” he says. “Now we charge $650 or $700 for two eyes, which is less than half of the old cost. I believe that’s mostly been possible because the cost of the disposable parts has really come down.”

“I think all of these devices work well,” says Dr. Milner. “It comes down to doctor preference. The important thing is that this device does two things. First, it has to heat the glands above the temperature required for the solid secretions to turn to liquid, the phase transition temperature. Normally, mei-

bomian gland secretions are liquid at body temperature, but when the secretions become abnormal, the secretions become solid at body temperature. Once that happens, you have to heat the lids up—usually to 108 degrees—to convert it back to liquid. Then, either you or the device need to massage the glands to get the oils out.

“The mistake doctors make,” he adds, “whether they’re accomplishing this with IPL, LipiFlow, iLux, eyeXpress, MiBo Thermoflo or the TearCare system, is that they fail to keep the patient on an anti-inflammatory drop so the oil glands can be maintained at a healthy level with less inflammation. That’s important. So don’t just clean out the glands; keep treating them with the anti-inflammatories and maybe Azasite or doxycycline as well.”

(Other tools that help address the signs and symptoms of patients suffering from meibomian gland dysfunction include devices such as BlephEx and NuLids that remove debris along the edge of the lashes; Cliridex, which kills Demodex; and Ocusoft and Sterilid, which help clean the surface of the lids.)

Additional Treatments

Many other options are also available:

• TrueTear. Dr. Rapuano says several of his patients like the TrueTear device. “It definitely creates tears,” he says. “The company also claims that if you use it multiple times a day it trains your tear-producing glands to produce more tears on their own.

“Not too many patients have taken us up on using it,” he notes. “We tell them about it, but it’s expensive and it sounds unusual to some patients. Having said that, patients who have bought it and tried it have mostly really liked it. Furthermore, if your symptoms are making you miserable, that out-of-pocket expense may seem reasonable. So it could become more mainstream in the future. So far, it’s not.”

• Serum tears. Dr. Rapuano says serum tears seems to be gaining a little more traction as a dry-eye treatment. “You get your blood drawn, and it’s sent to a special compounding pharmacy,” he explains. “They make tears out of your serum, freeze it and mail it to you. We think it probably helps with aqueous-deficient blepharitis because it has anti-inflammatory components, but it’s not likely to do much for conjunctivochalasis, floppy eyelid or pemphigoid.”

Dr. Rapuano notes that using serum tears requires effort, and it has to be repeated every several months. “We used to save this option for severe patients, but now we’re offering it to patients who are simply very unhappy,” he says. “It’s fairly expensive, and many insurances don’t want to cover it, but some patients find it very helpful and thank us for suggesting it. These are patients who have already tried many things on the treatment stepladder. This is toward the top of that stepladder, but it’s easy and safe and often successful. There are published papers that say it helps between 50 and 75 percent of patients.

“In the past serum tears were hard to get, but today, this option seems to be more readily available,” he adds. “Still, it’s not for everybody.”

• Scleral lenses. Dr. Rapuano says this is another treatment option he used to reserve for severe patients. “The Prose lens is one of the original, best ones,” he says. “Today there are several different Prose lenses, and lots of other scleral lens options.

“For patients with pretty advanced ocular surface disease, a scleral lens keeps a good tear coating on the eye,” he explains. “The tears are captured under the lens, all day long. The lens designs have gotten better and better, and more optometrists are fitting them, so it’s more mainstream now. It’s fairly expensive, including the fitting, but it will last for years. Serum tears have to be recreated every several months, for example, and the TrueTear device requires the purchase of single-use components every month.”

• Nerve regeneration. Another aspect of dry eye that’s now possible to treat is loss of corneal nerve function. “We un-

derstand more than ever that neurotrophic keratitis can play a significant role in dry eye,” says Dr. Milner. “In fact, DEWS II added the neurosensory component to their definition of dry eye. That validates the idea that we need to start looking at sensation as well.

“This is actually a two-way street,” he continues. “Dry-eye patients often become neurotrophic because the neural feedback loop breaks down as a result of lacrimal gland inflammation. That inflammation causes a decrease in the quality and amount of tears. Neurotrophic patients, who don’t have as much sensation, don’t blink as much, so they get dry eye.

“Now, however, we’re seeing a lot of new therapies that can help regenerate nerves,” he says. “One therapy involves placing an amniotic membrane on the cornea for several days. Two recent studies [sponsored by Tissue-Tech] found an increase in corneal nerve density and corneal sensation—i.e., nerve regeneration—after putting [Tissue-Tech’s] Prokera amniotic membrane on the cornea for five or six days.3,4 That improvement can last for nine months or more. [Dehydrated amniotic membrane such as Katena’s AmbioDisk, is another option to consider in such cases.] In addition, Oxervate, from Dompe Pharmaceuticals, was recently approved. It’s a recombinant nerve growth factor that

helps regenerate nerves.”

“Right now these treatments are being used for neurotrophic keratitis patients,” he notes. “In the future, though, you might see some of them become accepted as treatments for dry eye.”

A Helpful Dry-Eye Model

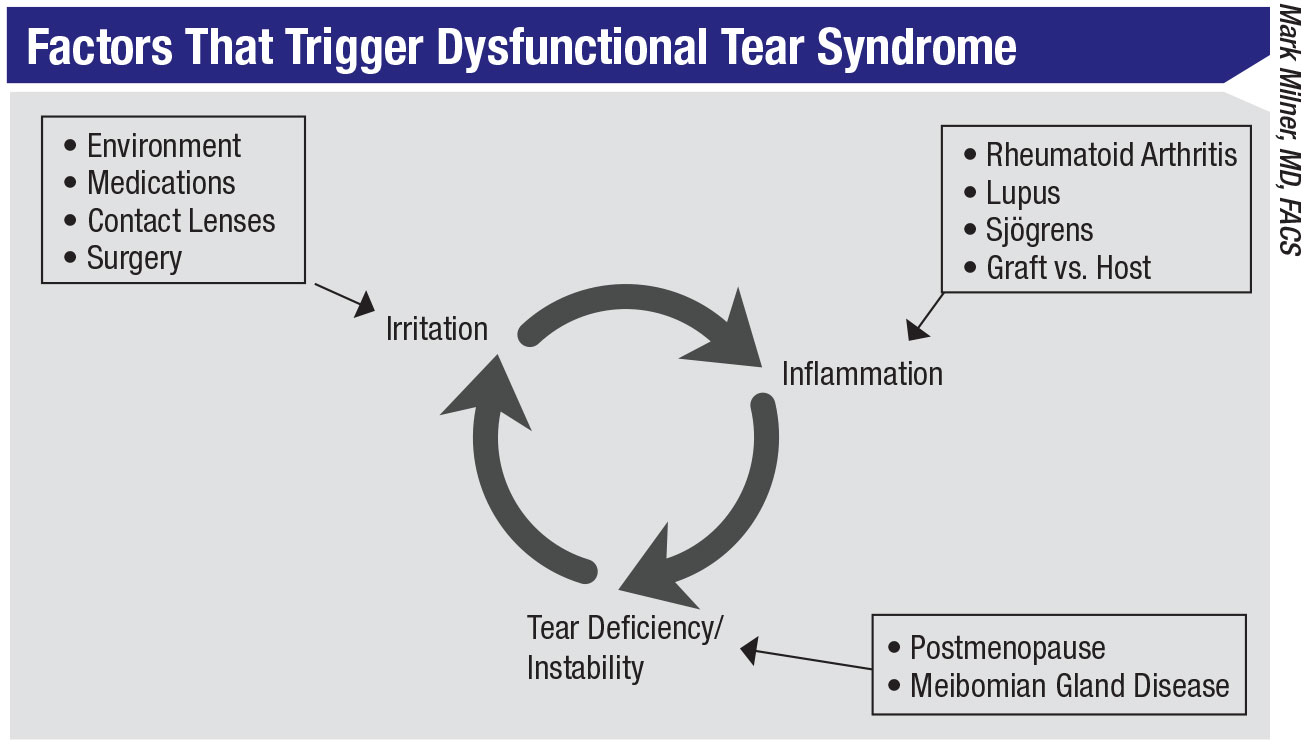

“In the end, dry eye is a carousel of inflammation,” notes Dr. Milner. “I think of it as a cycle that has three parts. Understanding this cycle leads to a much clearer understanding of treatment.

|

“The first part in the cycle is irritation,” he explains. “If the eye becomes irritated, no matter what the cause, the result is an upregulation of T-cells and production of cytokines; that leads to inflammation, which is the second part of the cycle. That, in turn, leads to the third part of the cycle: tear deficiency and instability. Inflammation shuts down your lacrimal glands, and your meibomian glands become inflamed. Goblet cells are lost. That causes an unstable tear film, with a decrease in volume and quality. That then leads back to the first part of the cycle—more irritation. That leads to more inflammation, and the cycle continues.

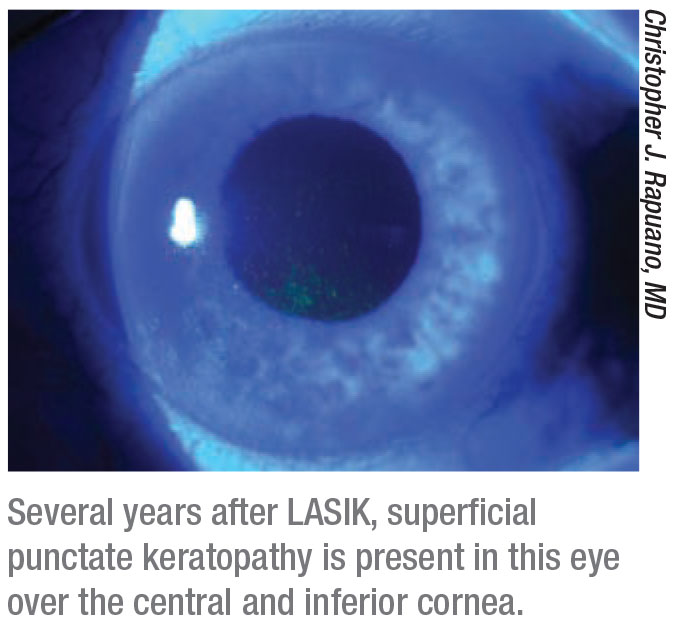

“The beauty of seeing the process this way is that a dry-eye problem can begin at any point in the cycle,” he continues. “For example, dry-eye triggers that jump onto the carousel at part one by causing irritation could include smoking, contact lenses, pollution, topical medications like glaucoma drops, refractive surgery such as LASIK or PRK, and cataract surgery. Irritants like these then lead to inflammation, the next part of the cycle.

“Other triggers can start the dry-eye cycle by causing inflammation first,” he continues. “These would include Sjö-gren’s, graft vs. host disease, Wegener’s, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and so forth. These can cause inflammation, leading to the next part of the cycle: tear deficiency and instability.

“The dry-eye cycle can also be started at the point represented by part three: tear instability,” he says. “These triggers can include menopause, because androgens, which are critical to tear production and meibomian gland secretion, are decreased; rosacea, which causes an unstable tear film; and oral medications that shut down your lacrimal glands. These can cause an unstable tear film, which leads to irritation, which leads to inflammation, and the cycle is underway.”

Dr. Milner explains that treatment always requires three key things. “First, address the thing that’s triggering the cycle, if you know what it is,” he says. “If the trigger is anterior blepharitis, use antibiotics and lid wipes or lid sterilizers. If the trigger is contact lens wear, limit lens wear or change the fit. If the trigger is glaucoma drops, get off the drops or decrease the preservative. If the trigger is rheumatoid arthritis, get systemically treated.

“Second, no matter what the trigger is, treat the inflammation,” he continues. “You won’t break the cycle until you do this. That’s where Restasis, Xiidra, and the new Cequa [Sun Pharma] come in. The third key thing is to treat the problem chronically. Use multiple medications if you need to, and treat it for long periods of time. The CEDARS algorithm can help you decide which specific tool and/or medication to use as your treatment.”

A Treatment Stepladder

Dr. Rapuano has what he calls “treatment stepladders” for the two main diagnoses he addresses—aqueous deficiency and blepharitis. “When a patient has aqueous deficiency, the lowest level of the stepladder is what I call ‘situational dry eye,’ ” he explains. “If a patient says his eyes get dry every time he drives in his convertible, artificial tears are fine. If a patient is using artificial tears more than three or four times a day, I switch the patient to preservative-free tears. If tear usage is more frequent than that, I switch the patient to a thicker preservative-free artificial tear such as Celluvisc, and may also start a tear gel at nighttime.

“If the patient still has a problem, I’d prescribe Restasis or Xiidra,” he continues. “The next step would be punctal plugs. Then I might try a short course of steroids. Rarely, we use bandage lenses. Finally we move to more heavy-duty options, like the TrueTear device, serum tears or scleral lenses.

|

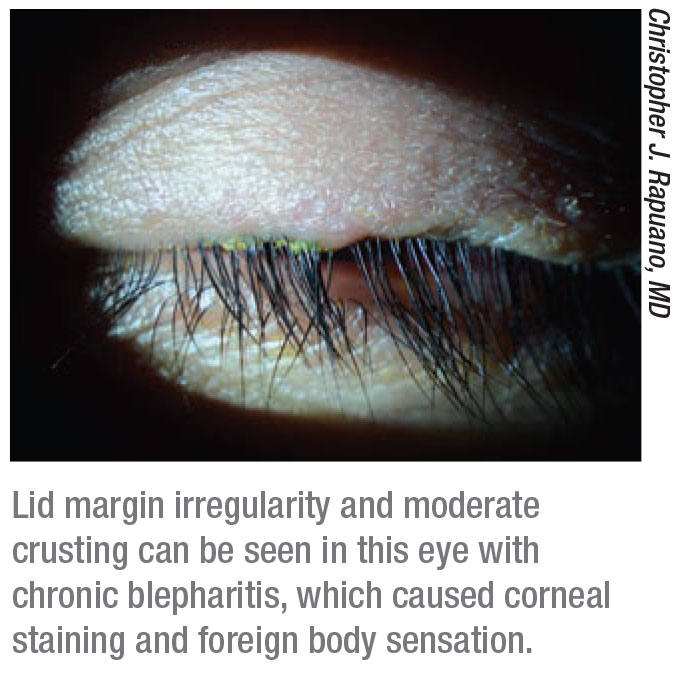

“To treat blepharitis we start with warm compresses and lid scrubs,” he says. “Next, we might try a spray cleanser like the product Avenova. I also typically have the patient use an antibiotic ointment, such as erythromycin, at bedtime. You can keep moving up the ladder and try Azasite gel drops at night, although I’ve found that product difficult to get these days. If that’s still not sufficient, you can try doxycycline or minocycline pills for about six weeks, sometimes longer. After that I’d try LipiFlow or IPL.

“In most cases I treat the patient for both types of problem, using options from both stepladders,” he adds. “Meanwhile, if you find that the symptoms are related to another issue such as conjunctivochalasis, I’d treat everything else first. If the patient is still symptomatic, I’d excise the chalasis.”

Strategies for Success

These tips can help you end up with a happy patient:

• Treat the right problem. Dr. Akpek says this comes down to two things: Listening carefully to the patient’s complaint and doing a thorough exam. “There are subtle differences among the different conditions that may present as dry eye,” she notes. “Some patients complain of lid redness; some complain of discharge; some complain of foreign body sensation; some complain of dryness or burning. Foreign body sensation and occasional excessive tearing could indicate conjunctivochalasis rather than dryness. If the patient complains of itching and redness, the problem might be Demodex, which can easily be eradicated. We need to listen carefully to the patient’s complaint and attack that exact problem.

“In addition, we need to do all the key tests,” she says, “Schirmer’s, corneal staining, osmolarity, conjunctival staining and a good slit-lamp exam of the surface. We need to check for conjunctivochalasis. If there really is an aqueous deficiency, that can be addressed by artificial tears, anti-inflammatories, or other modalities such as punctal plugs or serum tears. Patients with severe aqueous-deficient dry eye may have Sjögren’s. Many dry-eye patients will have meibomian gland dysfunction that needs attention.

“The bottom line is that we have to pay attention to what the patient is saying, correlate that to our ocular surface and tear-film findings so we understand the exact problem, and then attack that,” she concludes. “Then we need to try different treatment modalities in a stepwise manner, and be creative, based on what we find.”

• Measure signs only after stressing the ocular surface. “There’s a myth that patient symptoms and clinical findings don’t correlate,” notes Dr. Akpek. “On the contrary, there’s a perfect correlation—if you measure the signs under conditions similar to those that are bothering the patient. For example, when patients complain that they can’t see, it’s not that they can’t see to write a check; if you listen, they’ll say that they can’t see well long enough to read a book or do computer work. We don’t test that in the clinic.

“To make a more accurate assessment of the patient’s problem, sometimes you can take simple steps to recreate the stressed ocular surface that bothers the patient,” she continues. “There are many ways to accomplish this. For example, you can ask the patient to stare at something for several minutes, by asking them to read and fill out the symptom questionnaire. Or, you can check the corneal staining after IOP measurement. Numbing the ocular surface to take that measurement will have the side effect of reducing blinking and tear secretion; that will worsen the corneal staining from baseline. Once you approximate the corneal stress the patient is encountering in daily life, your measurements will reflect the level of irritation that triggered the patient’s complaint.”

• Don’t try only one treatment. “It’s easy to offer one treatment to a dry-eye patient and then move on to other concerns,” notes Dr. Rapuano. “I think doctors feel more comfortable treating problems for which they can offer a concrete solution. Furthermore, these are chronic conditions, patients are often pretty miserable, and managing them can take up a lot of chair time. On the other hand, we have a lot of treatment options we didn’t have even 15 years ago.”

• When deciding how to treat, think outside the box. “Right now we have Restasis, Xiidra and soon we’ll have Cequa,” notes Dr. Milner. “But when anti-inflammatories aren’t enough, doctors get frustrated: What else can I do? Well, for one thing, there are a lot of great compounded medications you can use off-label. We’ve had great success with them. For example, the product Metrogel is a great treatment for facial rosacea dermatitis. We order a compound of its main ingredient, metronidazole, into an ophthalmic preparation for posterior blepharitis or meibomian gland dysfunction, because it reduces inflammation on the meibomian glands and the lids just like Metrogel does on the face. If a patient can’t tolerate oral doxycycline, we compound doxycycline drops. If you really want to help patients who aren’t getting relief with the obvious treatments, think outside the box.”

• Make sure your patients understand that these are chronic conditions. “Some patients will do the aggressive treatment you’ve prescribed, but when they get relief they decide that they’re cured and stop the treatment,” says Dr. Rapuano. “You have to drum into your patients that this is a chronic condition that they’ll need to address their whole life.”

• Let the patient know you’re in this for the long haul. “We need to let these patients know that we’re not going to throw in the towel if one treatment doesn’t work,” says Dr. Rapuano. “Tell them that you’re going to try a treatment, and if it doesn’t work you’re going to keep trying options until you’ve improved their symptoms as much as possible. Patients want to

know that you’re not going to give up on them just because something doesn’t work.” REVIEW

Dr. Milner has financial interests with Allergan, Novartis, Shire, B+L, TearScience, Aldeyra, Eleven Biotherapeutics, Ocular Sciences, Kala, Eyevance and Refocus Group. He’s a speaker and consultant for Allergan, Shire, TearScience, Dompe and Sun. Dr. Akpek has received research support from Allergan and W.L. Gore & Associates and is currently a consultant with Shire, Novaliq and Regeneron. Dr. Rapuano has consulted for Sun, Bio-Tissue and Shire.

1. Donnenfeld ED, Perry HD, Nattis AS, et al. Lifitegrast for the treatment of dry eye disease in adults. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017;18:14:1517-1524.

2. Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, Chuck RS, et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: A Delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea 2006;25:8:900-907.

3. John T, Tighe S, Sheha H. et al. Corneal nerve regeneration after self-retained amniotic membrane in dry eye disease. J Ophthalmol 2017;6404918:1-10.

4. Morkin MI, Hamrah P. Efficacy of self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane for treatment of neuropathic corneal pain. Ocul Surf 2018;16:1:132-138.