Working in a referral-only practice and dealing with diverse surgical complications can be highly satisfying, but the road to mastering the surgical techniques that you’ll encounter in tertiary or quaternary care is a long and difficult one.

In this article, veteran surgeons discuss the types of procedures they perform in tertiary- and quaternary-level practice, weigh some of the benefits and drawbacks and offer advice for young doctors who may be considering this path.

|

Referral Practice Basics

A tertiary or quaternary practice is most likely to be found in a university setting. “There’s more access to technology and clinical research and development at an academic center,” notes glaucoma specialist Brian Francis, MD, of the Doheny Eye Institute. “You also have greater access to teaching opportunities. There are tertiary-level private practices as well, though. They’re often group practices, and more common in retina than in glaucoma. I get referrals from other glaucoma specialists as well as some non-glaucoma specialists.”

Realistically, it’s easier to get into tertiary or quaternary practice if you have a mentor who practices at that level. However, your mentor won’t teach you everything. “A mentor will get you started, but things change in the field, and 10 years later, you should be adding on to what your mentor has taught you,” Dr. Francis says. “You need to have the desire to constantly be trying new things and developing techniques yourself.

“There’s a good deal of patience involved as well,” he continues. “The surgeries are complex and require extra time with the patient, both in the chair and in the OR. This is a good place for those who want to be problem-fixers and pick up the pieces. If you’re not that type of person, or you want to deal with more straightforward cases, this might not be for you.”

He adds that the biggest advantage of quaternary practice is also its biggest disadvantage. “Quaternary practice is very exciting,” he says. “You deal with complex, intellectually stimulating problems. It never gets boring because you won’t be doing the same procedures day in and day out. The flipside is that it can be very stressful. In a quaternary practice, the buck stops with you. If you can’t fix it, there’s nobody else to send the patient to.”

Complex Procedures

When the surgery is more complicated than anticipated, or when the complexity level outpaces the surgeon’s comfort level, as Brandon Ayres, MD, of Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia puts it, those cases are usually referred to tertiary or quaternary subspecialists.

• Cornea. Dr. Ayres says that one of the things he enjoys about being a cornea specialist in a largely quaternary practice is that he’s able to fix almost anything in the front of the eye. “Being able to fix the lens, iris and cornea allows me to be a bit more of a complete anterior segment surgeon,” he explains. “Many patients who come in with other anterior segment problems also end up with corneal problems. The cornea tends to suffer from repeated abuse—multiple surgeries take their toll, and corneal edema is common.”

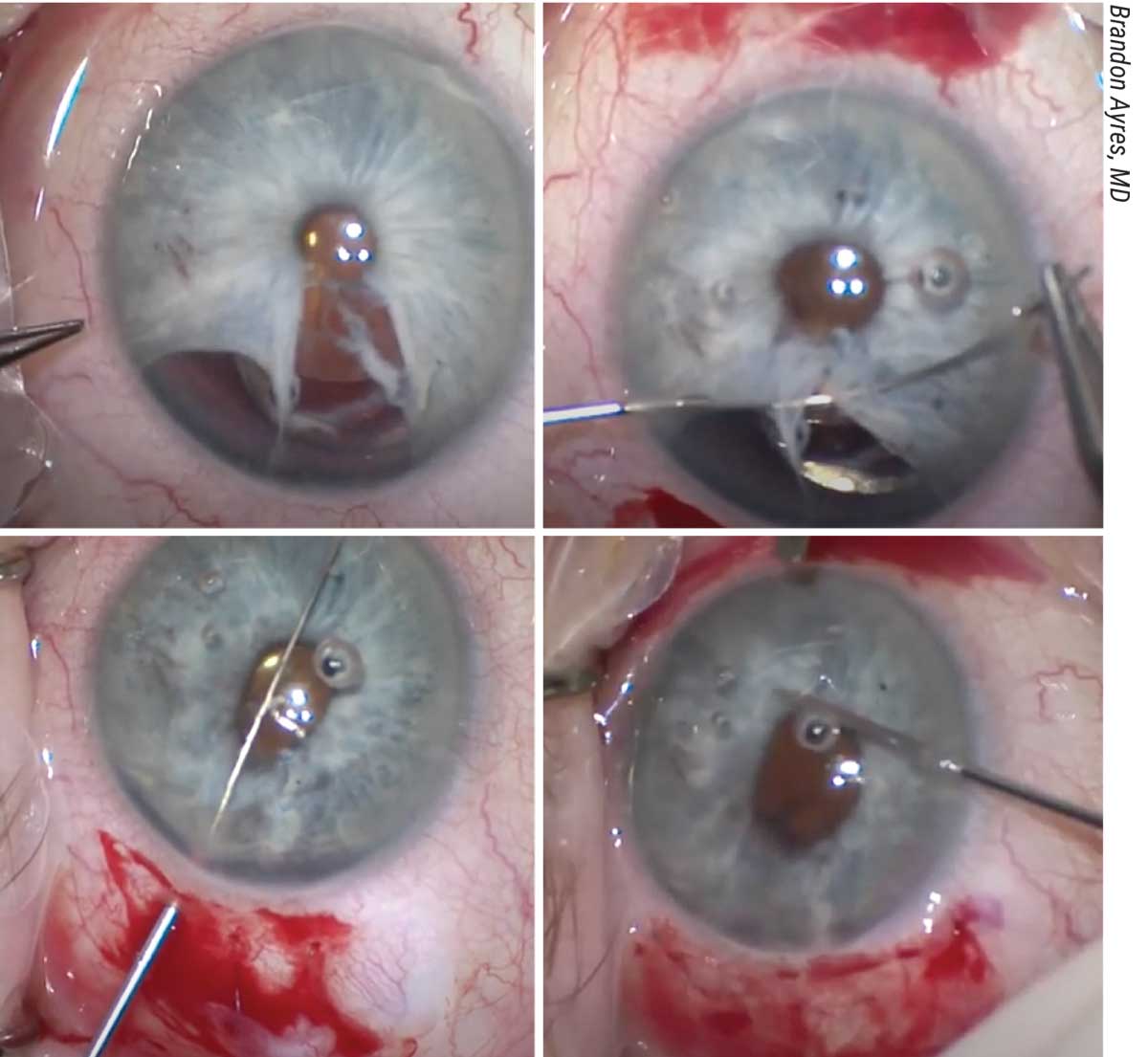

He says his surgical day is quite varied at Wills, which keeps his job interesting and him on his toes. “I see many patients for lens exchanges and dislocated IOLs,” he says. “Lens exchange patients are usually unhappy with the visual result they got—maybe the implant didn’t fully correct their vision or they’re unhappy with the quality of vision after a multifocal and want a lens exchange. We often see dislocated IOLs due to pseudoexfoliation or another preexisting condition that the patient has. Sometimes the support in the eye isn’t adequate to hold a lens and the surgeon opted to just hold off, or they had a problem placing the lens. We go back in and finish the surgery. Wills Eye also serves as a referral center for a lot of iris repair cases, such as those in which patients had IFIS (Figure 1) or iris damage during surgery.

|

| Figure 1. Iris repair usually requires performing multiple techniques. The patient in this case had an iris defect due to IFIS (A). The pupil was brought together using four-throw pupilloplasty (B), dialysis repair (C) and cautery (D).1 |

“Using newer techniques for corneal transplantation is an advantage as well,” he notes. “Lamellar corneal surgeries such as DSEK and DMEK help patients heal faster and achieve better vision. These procedures have been game-changers for some of our complex patients.”

When dealing with such complicated cases, outside-the-box thinking is often necessary for finding a surgical solution to patients’ problems. This means employing some alternative techniques. “Alternative techniques aren’t commonly used,” Dr. Ayres says. “I would never claim to be a better surgeon than anybody else. I think my surgical skills are probably about average, but I’ve gotten a lot of exposure to these complex cases, and that’s allowed me to apply what I’ve learned in different ways to help patients with their unique problems. Someone who doesn’t have the privilege of dealing with these specialized issues on a day-to-day basis might encounter a case like this only once a year or every other year, but we get to work on them three to four times a day.

“We become more facile at the procedures and learn additional tricks of surgery that can help various patients,” he continues. “The more tricks you learn, the bigger your toolbox becomes for helping other patients. The more you perform atypical procedures and techniques, the better you become at them.”

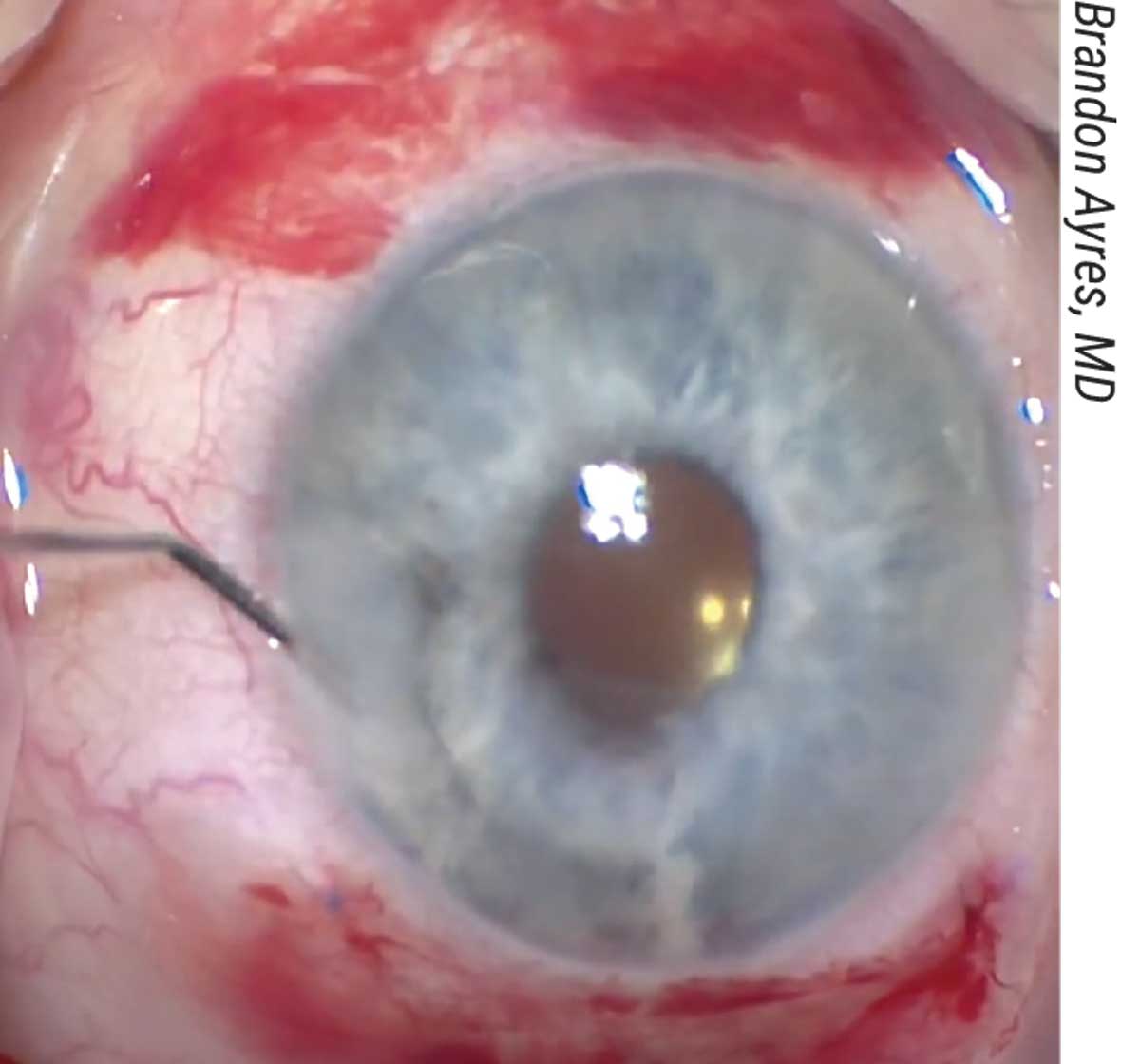

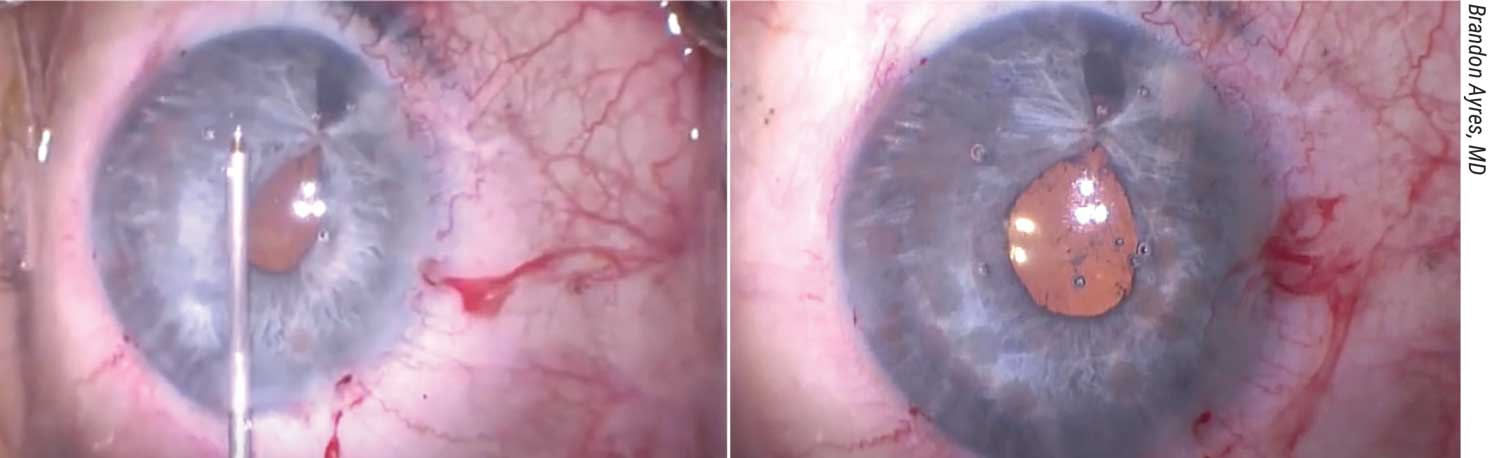

Some alternative techniques involve holding an instrument differently or in a different hand. Others might repurpose an instrument. “One example of this, passed down by anterior segment specialists, is using the retinal cautery unit for iris repair,” Dr. Ayres explains. “We attach the cautery unit to our phaco device and cauterize the iris to reshape it for patients with iris damage (Figure 2). That’s not what the cautery unit was made for, but it works beautifully and helps us get a better result in iris repair.”

|

| Figure 2. Iris repair in the case shown in Figure 1 resulted in improvement in iris appearance and decreased photophobia after the surgery.1 |

“Much of what we do consists of off-label procedures or difficult procedures, but many of those are what we enjoy the most,” says corneal specialist Sam Garg, MD, of the University of California Irvine, noting two of his favorites: Yamane fixation for an IOL exchange and performing DSEK in a complicated eye. “At my academic center, we see a lot of cases of corneal infections, corneal transplants and complications from cataract surgery such as corneal edema, dislocated lenses or a need for lens refixation. But part of being at a referral center isn’t always getting to do the ‘easy’ cases. Sometimes it involves cases with difficult patients who didn’t understand what they were getting into and now it’s your job to help them understand that nothing was done wrong in their original surgery, but that their expectations may have been unrealistic.”

• Retina. The patients whom Mitul Mehta, MD, sees at his UC Irvine-based retina practice usually fall into two groups, he says: either their disease was managed elsewhere and a complication developed afterwards, or the outside practice didn’t have the equipment necessary to perform a specific procedure. He often sees patients for diabetic retinopathy, tractional retinal detachments, ocular trauma, ruptured globe repair, intraocular foreign body removal, choroidal hemorrhages, dislocated IOLs that have fallen into the vitreous and aphakic patients who need a secondary lens but lack a capsule or zonules.

“For cases such as PVR detachments, where patients may have had previous failed surgeries, we remove the lens using a pars plana lensectomy,” he says. “Oftentimes, the cornea is damaged as well. In those cases, we work with our cornea colleagues who perform a corneal transplant with a temporary keratoprosthesis, which allows us to obtain a good enough view through the cornea to remove the lens and work in the vitreous cavity. We often put in a scleral buckle or do a large retinectomy, where we remove large sections of the retina to allow the retina to lie flat after peeling the membranes. In cases where the membranes are very stuck to the retina and the retina is detached, we’ll put in a chandelier light, so we have two hands available to peel the membrane off the retina.

“When we encounter intraocular foreign bodies, we do a vitrectomy to remove the item from the back of eye,” he continues. “If it’s metallic, we use an intraocular magnet to pick it up, so as not to damage the retina while trying to grab the item. If it’s embedded in the retina, we make sure to secure and stabilize the retina before we pull it out in order to avoid the eye filling with blood. The entry wound isn’t usually suitable for removing the foreign body, so we close the entry wound first and make a separate wound to remove the item. The latter goes for dislocated intraocular lenses—we often need to make a new wound to remove the lens or the lens fragments, after we cut it. We’ll fixate the new lens to the wall of the eye.”

• Glaucoma. Most of the cases Dr. Francis sees have either failed prior glaucoma procedures or have complications from prior glaucoma surgeries, such as malpositioned MIGS devices or malpositioned tubes, leaking trabeculectomies, dysesthesic blebs, blebitis or tube erosions.

“In my practice, I also do a lot of UGH and IOL malposition cases,” he adds. “I got into treating UGH syndrome because one of my specialties is using the ocular endoscope system for doing ECP and lowering aqueous production, but also for intraoperative intraocular viewing. I can look at the sulcus and anterior retina in real-time and diagnose and treat some of these weird problems.”

He also uses the endoscope to check for IOL problems in the sulcus, foreign bodies, other causes of UGH syndrome and malpositioned tubes. “These are some of my favorite surgeries,” he says. “I also enjoy the MIGS procedures, and I do a fair number of tube revisions too, though they aren’t as enjoyable because they can be a little difficult sometimes.”

He says he often combines procedures to find alternative ways of controlling patients’ pressures. “If a patient has a recurring tube erosion, we’ll find an alternative position for it and place it in the pars plana or sulcus to keep it away from the cornea or the limbus in order to reduce corneal damage and the possibility of erosion. If we have to take them out, we can combine some of the non-filtering procedures such as ECP or Micropulse CPC with or without the angle-based MIGS procedures as well.”

|

| Figure 3. Anterior segment surgeons sometimes turn to the cautery unit (which was intended for retinal applications) to reshape the iris. In this case, a young female patient presented with a ruptured globe due to blunt-force trauma, a traumatic cataract and an incarcerated iris. After cataract removal and enlargement of the capsulotomy, the iris was repaired using a sliding knot and thermal iridoplasty. The iris edges at the scleral incarceration were brought together with 10-0 polypropylene and a CIF-4 needle, forming a teardrop-shaped pupil. A modified sliding knot (also known as a modified Siepser knot) was tied with three throws to close the iris defect. Using 25-gauge intraocular diathermy on a very low setting on the anterior segment machine (about 11 to 12 on the Alcon Centurion), small cautery burns were made on the iris (A) to re-shape and round out the pupil (B). Dr. Ayres advises against being overly aggressive with cautery since there will be some transillumination defects where the cautery burns were made.2 |

Uncomplicating the Discussion

Many patients seen in tertiary and quaternary care are fixated on why their complication occurred or what the other doctor did “wrong.” “The patients who come to us are already not doing well,” Dr. Ayres notes. “Many are angry, scared or upset, and they’re looking to me to correct a complication or problem that was encountered during their surgery or was the result of a surgery. When I’m managing these patients, I’m not only thinking about how to achieve the best outcome, I’m also trying to make sure I shine a positive light on the referring surgeon.

“A patient may say, ‘How could this have happened? Why me? Did the surgeon do something wrong?’ I tell them that all surgeons experience complications, including myself,” he says. “Nobody’s perfect. Some things are out of the surgeon’s control, such as if a patient has some bleeding or a floppy iris. I often tell patients, ‘You’re lucky that that surgeon was there to take care of this and limit the potential problems to where they are so we can still get you fixed. Had this been a less skilled surgeon, you may have been in a worse place than you are now.’ We never tell patients that something was ‘messed up.’ ”

Dr. Mehta advises every specialist to have a standard spiel prepared for their patients before surgery. “I always make sure to mention to all my patients that people can have strange reactions to medications or the surgery itself that could lead to loss of the eye entirely,” he says. “I impress upon them that there’s always a risk to intraocular surgery, but that we do the surgeries because we believe they’ll benefit the patient. You can go into the specific details of the more common risks for a given surgery, but I always start with that so the patients understand that surgery is serious and shouldn’t be taken lightly, even for a procedure that I would consider simple for me.

“Patients don’t know what a procedure really entails or what the postoperative course is going to be like,” he continues. “They need to know what they’re getting into. Many patients believe all surgeries can be done with lasers outside the operating room. There’s a lot of education that needs to happen. It doesn’t have to take long, but it should hit the major points.”

Accepting Risk

Surgeons who work in tertiary and quaternary care say they find their jobs highly satisfying because of the challenging cases and cutting-edge procedures they often perform. However, they all agree that higher reward also means higher risk. “We’re dealing with patients who have bigger-than-average problems or are more complicated than average,” Dr. Ayres says. “Not every patient is going to have a good outcome. When you’re sent patients who already have a surgical complication, you’re accepting some of the risk that was given to you by the other doctor.”

Some patients will develop complications such as retinal detachments around the period when you first evaluated them and their scheduled surgery. Did the complication develop after you saw the patient or did you miss it on the evaluation? “You’re taking on some of the risk of not seeing that retinal detachment complication and not sending that patient to see a retinal specialist,” Dr. Ayres says.

He uses a measure of caution. “I’ll tell a patient, ‘I think I can fix your problem, but I want you to see a retinal specialist in a couple of days to make sure your retina makes it through the surgery.’ I cover my bases with help from my colleagues who are experts in other fields to make sure I’m not missing anything, and that we give the patient the best outcome and care possible.”

As with any case, but especially with complex patients, it’s important to document your cases thoroughly. “I don’t have special insurance for doing complicated cases, so I make sure to document everything well in the chart and discuss things well with patients,” Dr. Ayres notes. “That helps to limit your liability.”

Accepting Limitations

Dr. Garg points out that not every case will have a surgical solution. “You have to consider whether intervention is the right thing for the patient,” he says. “Sometimes surgery won’t achieve meaningful improvement, and it’s better to tell the patient that more surgery won’t be fruitful. That takes time to understand. When you first start practice, you may believe that you can help any patient who comes in, but these aren’t straightforward cases. We do our best, and sometimes we hit a home run but other times we don’t. That’s part of the job.

“It can be a difficult conversation to have,” he continues. “The patient may not understand why you’re not doing more surgery. They may have believed, after having seen other doctors, that you could help them, and unfortunately, that’s not always the case.”

Dr. Mehta says that the patients whom retinal specialists are unable to treat are usually those who have a disease for which there are no treatments, such as dry macular degeneration with geographic atrophy. “Currently, there’s nothing FDA-approved and nothing on the horizon that looks like it’ll improve patients’ vision,” he says. “Everything right now is focused on slowing the progression of the disease. These patients aren’t going to get any better no matter what I do, but I can make sure to follow the other eye, look for other diseases and try to minimize the effects of their disease.”

“There are some glaucoma cases where there’s nothing you can do, but it’s pretty rare,” says Dr. Francis. “Unless the patient has no light perception, there’s usually a glaucoma procedure you can offer. It pays to be familiar with all of them to increase your options.”

Time Isn’t Money

“If you have a business-development mindset and want to build a large practice and make a lot of money, quaternary practice isn’t the best way to do it,” Dr. Francis points out.

Performing these complex procedures can take a long time, and the pay isn’t always equivalent to the amount of time they take. “A PVR detachment that takes two to three hours to repair doesn’t pay any more than a retinal detachment repair with a mild membrane peel,” Dr. Mehta says. “A case like that could take a fraction of the time and pay almost as much or just as much as a case that takes several hours.”

“Corneal transplant surgeries or IOL exchanges lose you time in the OR, in a sense,” Dr. Garg notes. “These surgeries take much longer than a 10- to 15-minute cataract surgery and decrease your opportunity for seeing ‘revenue-generating’ patients because you see complex patients many more times than you would a cataract patient in the global period.

“At the same time, the satisfaction level is different,” he continues. “When you have this skillset, it’s not all about dollars and cents. It’s about where you can make the biggest impact for these patients and for your community. If you’ve been trained to do these special techniques, you can’t look at your practice in only financial terms, because if you do, it doesn’t always make sense to take on these more challenging cases.”

The Business of Referrals

One thing that many young doctors don’t consider as residents or fellows is where their future patients will come from. “It’s way more work than I thought it was going to be,” Dr. Ayres admits. “I don’t advertise myself to the general public. I rely on other doctors to send me their problematic cases. I not only need to perform for the patients so that they do well, I also need to perform well so that referring doctors who may feel responsible for some of the patient’s complication or complexity will think of me to fix the problem. I need to put myself out in the community and show people my work, like a portfolio. I never thought that would be part of my business, but it’s a major part.”

Dr. Mehta says it’s fundamentally important that you get to know your community if you’re embarking on tertiary or quaternary practice. “Every area has some sort of ophthalmology society, and it’s a good idea to become a member of those societies,” he says. “Go to the meetings and get to know who the other doctors are in your area so they can refer patients to you. They need to know what you can do. One benefit of being a specialized surgeon is that there will always be a demand. Complications happen, regardless of region.

“I’m a member of my local ophthalmology society,” he continues. “I’m on the board, and the reason I’m on the board is that I went to every meeting and people saw me there and saw that I was active. I have separate business cards with my cell phone number on them that I give to other doctors. They call or text me all the time and send me patients. This helps me build my practice.”

He says it’s a good idea to offer continuing education for local optometrists. “We don’t do that at the university, but we do offer CME for general ophthalmologists,” he notes. “Once word gets out that you can handle very complex cases, people will send patients your way. You’ll be sent some routine cases too. The routine cases will fill up your regular clinic days and help to build your practice at the beginning. Sometimes I get a patient who doesn’t have a retinal issue, and I’ll either send them to the proper person or if it’s simple, I’ll fix it myself.”

Advice For Young MDs

Mastering complex surgical techniques is a long but rewarding process. Here are some words of wisdom to keep in mind for expanding your skillset and setting yourself up for success:

• Stay current with your CME. “Continuing education is very important,” Dr. Francis says. “The major societies all have programs for skills transfer that are very valuable. You can learn from experts and develop new skills at meetings, such as suturing IOLs or IOL fixation or different types of glaucoma procedures. We run a MIGS lab at the Academy every year. You may attend a lab course and end up deciding that it isn’t for you. That’s okay, but at least you tried it and made an effort to incorporate something new into your practice.”

Dr. Garg adds that “Even if you don’t do these complex techniques on a day-to-day basis, sometimes just knowing how to approach a difficult situation can prevent patient harm and morbidity. You never know when you’ll be in a situation when things may go awry. These techniques can be difficult to master, and they take more time and effort to learn.

“It doesn’t always go well in the beginning,” he adds. “You might see Dr. Ayres do a video and try it yourself, and it doesn’t go the way Dr. Ayres showed it. There’s an opportunity cost to learning these techniques, but the payout is huge from a personal satisfaction standpoint and from a patient-benefit standpoint.”

• Seek feedback from your mentors and colleagues. “Whether you feel comfortable with a procedure or not, you have to make use of all the resources you have available to you: your network, societies like ASCRS and AAO, mentors, published talks and videos, lectures and courses,” Dr. Garg says.

The network of mentorship and professional societies is key for expanding your skillset, but ophthalmology meetings aren’t everyday occurrences. “Daily social interaction with your colleagues is just as important,” Dr. Mehta says. “If you practice in a group setting or at an academic institution, you have easy access to your colleagues to discuss cases or comanage with other specialists and subspecialists. That’s a major advantage.”

• Challenge yourself to leave your comfort zone. “Many of the techniques I perform now I didn’t learn during residency or fellowship,” Dr. Ayres says. “YouTube, ASCRS, AAO and wet labs are great resources for learning. Talk to friends who’ve done these cases before and get outside your comfort zone a bit.

“I encourage our residents and fellows to keep an open mind,” he says. “One of the things I like to tell our fellows is, ‘Say yes—if you feel comfortable.’ You won’t learn the skills unless you try. Before I became very comfortable doing these procedures, I’d tell patients, ‘I’m going to do the absolute best job I can, but if for some reason I’m not able to get the lens out, we’re going to leave it and you’ll be okay. My goal is to do no harm. I think I can help you.’ You try and try and get better and better. And eventually it’s really a rare day that you can’t get a lens exchange done.”

• Set personal boundaries. “Nobody can last as a resident or a fellow forever,” Dr. Mehta says. “Working 80 or 100 hours a week isn’t sustainable if you want to have a life outside of work. You need to set boundaries and set up a system where there will be people to cover you for calls or your patient messages—patients call us with very simple questions, and they do expect an answer. Someone from your office should respond to them. In an ideal situation, the doctor does only what the doctor alone can do and not too much more than that. This isn’t the case for most practices or universities, but that’s a good goal to have. You should try to be supported as much as you can. Delegating tasks will help your days move and give you extra time to think.

“Many people in quaternary or tertiary referral tend to be academically-minded and do some research or go to conferences,” he continues. “In order to get the most out of conferences, you need time to think. You can’t be running 24/7. I set aside half days when I don’t see patients. During that time, I work on academic pursuits that interest me. That’s what keeps you excited, instead of getting burnt out.”

• Remember the “Three As” of building a practice. These are ability, availability and affability, says Dr. Francis. “You need the surgical skillset; you need to make yourself available for the patient and that Friday afternoon high-pressure case; and you need to build rapport with both the patient and the referring doctor,” he says. “Communicate well with the patient and with the referring doctor about the patient’s status and what you’ll do for the patient.”

These specialists agree that tertiary and quaternary care are highly satisfying fields. “You’re helping patients who wouldn’t be able to get that level of care elsewhere,” Dr. Francis says. “You dedicate yourself to these types of patients. In the end, it’s very rewarding. I wouldn’t want to do anything else.”

Dr. Ayres is a consultant for Alcon. Drs. Mehta, Garg and Francis have no financial disclosures related to their comments.

1. Ayres B. Repair of iris defect caused by IFIS. YouTube. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://youtu.be/kvz3Tfn_YD0.

2. Ayres B. Traumatic cataract removal with iris repair and thermal iridoplasty. YouTube. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://youtu.be/U9KI5HnieT8.