|

Blame it on the accuracy of LASIK and the graying of America: A-scan biometry needs to be dead-on to satisfy today's cataract patients and refractive surgeons. Candidates for intraocular lenses are better educated about cataract surgery. Frequently, they are younger and more demanding about postop outcomes because they have longer to live with their pseudophakic eyes. This article reviews how accurate biometry is now, more than ever, an important part of successful cataract surgery and offers some recommendations for those taking and reading the A-scans.

Technique Matters

The buzz around A-scans consists mostly of technicians' opinions on techniques that have worked best over the years. And even these divided camps fall into only about three categories: A-scan by applanation, A-scan by immersion, and the use of Zeiss-Humphrey's IOLMaster.

"Biometry truly is an art," states Cynthia Kendall, president of I3 (Innovative Imaging Inc.) in Sacramento, Calif., a manufacturer of high-resolution A-scan and B-scan instrumentation. In a world where faster is often seen as better, she is pleased to see the tide turning toward the practice of immersion biometry, which by its nature re-quires a well-trained technician who will be capable of correlating measurements with a patient's history.

Rhonda Waldron, senior associate in ophthalmology at the Emory Eye Center in Atlanta, agrees that problems are encountered when an ophthalmologist thinks that you can put an A-scan machine on its automatic settings and get anyone in the office to run it. "There's no magic box," she cautions.

Both Ms. Kendall and Ms. Waldron, as well as Bill Menke, director of sales and marketing in the United States for ultrasound maker Quantel Medical, are advocates for the immersion method.

"I have been a very strong proponent of immersion A-scan technique utilizing the Prager immersion shell," offers Mr. Menke. "We always furnish a Prager shell with our Axis II Precision A-scan unit. Our representatives teach the immersion method in the doctor's offices."

Ms. Waldron also endorses non-contact biometry: "The only absolutely accurate axial length measurement is going to be through a non-contact technique. That's either immersion with one of the shells, be that Prager or Hansen, or with Zeiss' IOLMaster on eyes that do not have dense cat-aracts or other media opacity."

Plunge into Immersion

Though the non-contact methods eliminate the error of corneal compression and produce accurate, reproducible A-scans, nearly 80 percent of ophthalmologists in the United States still use the contact technique in their practices—mainly because doctors and technicians are afraid the immersion method will take longer, be difficult to learn or require all new expensive equipment.

|

The contact method persists in some cases, says Ms. Waldron, because ophthalmologists have been fortunate in making accommodations for the method's shortcomings.

For example, a doctor may have learned to estimate his technician's contact indentation with the probe, she offers. Over time, he has created his own personalized A-constant or "fudge factor" to use in IOL calculations, and it's been successful. "This may work okay in most cases," Ms. Waldron explains, "But you really can't indent the same amount every time, and if the technician leaves the position, another person could never have the same corneal compression, and the formula will no longer work."

If the continued use of contact biometry is due to the practice's ownership of an older A-scan unit, Ms. Waldron says that buying a new machine should not be a great concern. "You can get a good machine today for $6,000 or less," she estimates, "Or possibly upgrade the one you own."

One more option in the marketplace is the IOLMaster produced by the Humphrey Division (Dublin, Calif.) of Carl Zeiss Ophthalmic Sys-tems Inc. The IOLMaster uses light rather than sound to measure axial length, corneal radius and anterior-chamber depth of the patient's eye. Biometry experts interviewed for this article agreed that the IOLMaster is a powerful tool. They did note, however, that it has limited success with patients who have particularly dense cataracts, posterior subcapsular cataracts, other hazy media, or those patients who can't fixate. "It also can't give you the most accurate anterior chamber depth and lens thickness data required for the latest IOL formulas," says Ms. Waldron. These patients must be sent to a technician skilled in A-scan. Conversely, "there are areas where the IOLMaster really shines," as Ms. Waldron puts it, as in cases of a posterior staphyloma in the macula or eyes filled with silicone oil. "In these cases, as long as the patient can see the fixation target and his cataract isn't too dense, you can get his axial length easily on the IOLMaster," she says.

Experience Is King

Though a reliable machine with the features needed to obtain a high level of accuracy is a good starting point, the user must have a good technique to match it.

Ms. Waldron cautions her students that they can't just set their machines on auto mode and be done with it. She recommends starting with a complete review of the patient's history, the details of which can affect the measurement. For example, the biometrist should know the approximate axial length that she is going to find in a myope vs. a hyperope.

|

Past surgery will also affect what the biometrist sees. An eye that has a scleral buckle will measure longer than the fellow eye, Ms. Waldron notes.

The best technicians know that each patient is different and is going to take some detective work, she says. She offers a few examples for which the observant biometrist will be prepared: A patient whose chart indicates he has an eye filled with silicone oil will need adjusted velocity settings which are programmed in to newer A-scan units, "or else you're going to have to do some math," she says. The technician must also be willing to take a lot of measurements for a patient with a challenging eye and be willing to try something else if her first at-tempts fail. For example: "If your patient is a high myope with an oval-shaped eye or with a posterior staphyloma in the macula, the macula is on a slope. You can't get perpendicular to a slope, so there is no way to get a high-quality retinal spike on that eye, and your numbers will vary greatly."

The enterprising biometrist will move to the B-scan to measure the vitreous length along the visual axis, and use that number to compare to the A-scan measurements to find the matching vitreous length, and use that in the calculations. "Another good option for a hard case like this one is the IOLMaster, assuming the cataract isn't too dense for its use," she recommends.

The B-scan is usually used for diagnosing and documenting ocular pathology, but according to I3's Ms. Kendall, the B-scan can serve as an adjunct to A-scan when it is impossible to acquire a valid echo pattern. "The use of the B-scan to confirm the axial length of a questionable A-scan will greatly improve your accuracy," she says.

Common Mistakes

Ms. Waldron shares some common problems she helps solve for her students at her educational sessions.

One common error, she notes, is the corneal compression inherent to the contact technique. Her recommendation: While you are taking the reading, monitor the anterior chamber depth on your screen. You'll be able to tell which has the most indentation. "If you see a 3.5 mm vs. a 3.3 mm, you know you have indented more on the one reading 3.3 mm. The deeper the anterior chamber depth the better," she advises. "Of course, immersion will eliminate this error altogether," she notes.

|

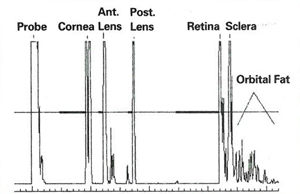

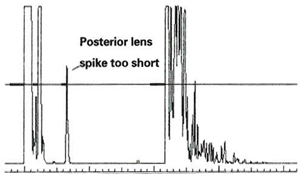

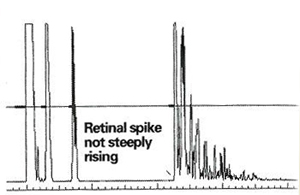

"Too many technicians are taught to look for four echo spikes instead of five. This is wrong," she mentions. "You can fix this by tilting to aim the sound beam more temporally."

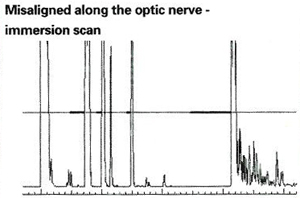

"It's common to get errors because of optic nerve alignment, since the nerve and macula are close together. In some patients this can cause a significant error of a millimeter or more, such as in glaucoma patients with optic nerve head cupping, or in the patient with a full disc or optic disc drusen," she cautions.

Accurate axial length measurement, regardless of the A-scan method technique used, will contribute to proper IOL selection, successful surgical outcomes and the satisfaction of both the patient and the ophthalmologist. REVIEW