Achieving Good Dilation

Miosis is a potential problem with femtosecond-assisted cataract surgery that you can head off at the pass; it occurs in up to 32 percent of cases according to one study.1 Here is how experienced surgeons deal with it.

Though the miosis occurs after the femtosecond step, surgeons take preop steps to prevent it. “I published a small study a few years ago explaining how to prevent the 25-percent risk of pupillary miosis after the femto step,” says Singapore’s Ronald Yeoh, FRCS, FRCOphth, DO. “Miosis can be reduced significantly by the simple expedient of using an NSAID drop along with the dilating drops an hour or two before surgery.”2

Robert Weinstock, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Florida, Tampa, says timing also plays a role. “Give the patient extra time in the holding area,” he advises. “Don’t bring him back to surgery until you’ve given him adequate time to dilate. After that, we use a Shugarcaine type of mixture containing lidocaine and epinephrine on small pupils right after we make the cataract wounds but before we put in the viscoelastic. We also use a drop of 10% phenylephrine in all patients immediately after the femto laser step, unless they have a cardiac disorder or hypersensitivity to the drug. We also may use the phenylephrine in preop for a patient who’s not dilating, but that’s not routine. In addition, we will use Omidria as long as it’s on a plan or the insurance covers it.

“There’s something else to note about small pupils,” Dr. Weinstock continues. “The closer the capsulotomy is to the edge of the pupil, the more collateral laser energy will hit the pupillary rim, which can induce some miosis. The patients whose pupils shrink down a little and get some miosis right after the laser treatment are the ones who start out with smaller pupils, because you’re getting the laser energy so close to the pupillary margin.”

|

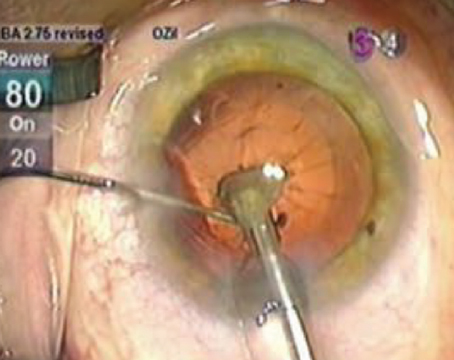

After femtosecond laser capsulorhexis is completed, laser cavitation bubbles and intervening uncut areas in between the bubbles circumferentially can be seen, representing an incomplete cut. Surgeons say these intervening uncut areas are vulnerable locations where radial tear-out may occur. |

Even if the patient’s pupil is relatively small, some surgeons are able to create a usable capsulorhexis. “If he hasn’t dilated completely, you have to make a decision—and sometimes you can’t make that decision until he gets to the laser—about how big of a capsulotomy you can squeeze inside the pupil,” explains Dr. Weinstock. “Every doctor has a different comfort level; some will shrink capsulotomies down to sub-5 mm, and some will shrink them down to sub-4 mm. In general, though, if you’re uncomfortable that the pupil is too small once you dock the patient, you can bypass the laser capsulotomy and fragmentation and just do the astigmatic correction with the laser. If you feel the pupil is big enough to do the case successfully, you can shrink your standard capsulotomy, say, from 5.5 mm to 5 or 4.8 mm, and just squeeze it inside the pupillary margin.”

Applanation and Docking

Occurring in about 2 percent of cases, a suction break is one of the recognized complications of femto-assisted cataract surgery that can momentarily, or permanently, derail the femto portion of the procedure.1 Here are surgeons’ thoughts on achieving good applanation and maintaining suction.

London surgeon Sheraz Daya says the quality of the applanation can directly affect the quality of your femtosecond treatment. “You need to applanate without producing wrinkles on the posterior aspect of the cornea, because wrinkles will cause the laser energy to be focused in the wrong place,” he says. “In fact, you won’t get any effect at all because the cavitation bubbles won’t form due to the laser being out of focus. That’s how you get tags and skips in the capsulotomy. We use the so-called soft-docking method in which we put fluid in the suction ring and applanate just enough to make contact with the eye in the center but leave a meniscus of fluid in the periphery. That way, we can see whether we’re producing wrinkles in the posterior cornea or not.”

Dr. Weinstock says patient awareness can help avoid suction breaks. “You have to make sure the patient is lightly sedated,” he says. “If she’s overly sedated, she will fall asleep, and then suddenly wake up with a jerk. It’s when you have this kind of patient movement that suction breaks and complications can occur. It’s a situation very much like LASIK, in which you can use your voice as a ‘vocal local’ anesthetic; with a calming voice, tell the patient what you’re doing at each step to keep her calm.

“If you do get a suction break, unless you haven’t done any femtosecond treatment at all, my advice is to abandon the surgery,” Dr. Weinstock continues. “Practically speaking, you can usually finish the rest manually. Also, if any complication occurs with the femtosecond surgery—whether it’s an incomplete treatment or a suction break or something else—make a note of it, because afterward the patient may go back into holding or you may have done some other tasks before seeing her again for the cataract portion, and you’ll need a reminder that something unusual occurred.”

Capsulotomies

In the study cited earlier regarding miosis issues, the surgeons also experienced a 20-percent incidence of issues with the femtosecond capsulotomy, including capsule tags and bridges, and a 4-percent incidence of anterior tears.1 Surgeons say, however, that you can dramatically reduce your risk of these problems by making certain adjustments to the laser, as well as to your technique.

Springfield, Mo., surgeons Shachar Tauber, Wendell Scott and their colleagues have won the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery’s best paper of session award two years running for their work on adjusting the femtosecond laser’s settings to create better capsulorhexes. “First, if at all possible, use a programmable setting that lets you center the capsulotomy on the geometric center of the capsule,” Dr. Tauber says. “If there’s a lot of tilt in the lens—such as when the patient has a Bell’s phenomenon—either reacquire the image to get a more anatomically correct one or turn off capsule centration and use pupil centration so you’re not using the laser on a tilted lens or eye. Using it on a tilted lens can result in partial cuts into the capsule in one location and deeper cuts on the opposite side. Also, along with pupil centration, you can customize the diameter. We use a 4.9-mm diameter usually, but can go up to 5.1 or 5.2 mm or so. There may be a benefit to doing a large capsulotomy, such as 5.5 mm, in patients with pseudoexfoliation because there may be less chance of phimosis and less stress on the zonules later on. A larger, more consistent capsulotomy also may help in cases of late IOL decentrations/dislocations.

|

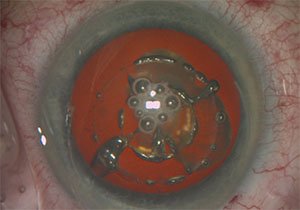

As this laser pre-chopped lens is tilted, the deeper parts of the lens where the laser pre-chop is incomplete are revealed. Surgeons note that the femtosecond laser only produces a potential cut, not a true cut, to begin with. And, for denser lenses, the laser sometimes can’t effectively reach the deeper part of the lens, so the laser pre-chops themselves could be entirely absent. |

“One of the most pressing issues we found when reading the femtosecond cataract literature is the increased risk of capsular tears,” Dr. Tauber continues. “Scanning electron microscopy studies were showing how aberrant laser pulses create almost a postage-stamp capsulotomy and/or extra pulses on the uncut part of the capsule. In response, my colleague Dr. Wendell looked at the parameters we could change on the femto capsulotomy, and one was the vertical spacing between the rings of photodisruption the laser creates as it makes the capsulotomy. The laser comes with a 10 µm vertical spacing, so in 2015 we changed it to 15 µm and immediately noticed a statistically significant decrease in the amount of ‘slivers,’ or little pieces of capsule that flop around at the end of the case, as well as a decrease in our already low anterior capsule tear rate. This year, we did another 1,000 cases in which we increased the vertical spacing to 20 µm. The sliver rate didn’t change significantly, but the anterior capsular tear rate decreased to 1:1,000, which was a significant improvement.

“The other change we implemented was timing the capsulotomy so that it’s synchronized with the patient’s exhalation,” Dr. Tauber adds. “This is because an exhale is very steady and involves limited head movement, while an inhale involves more head movement that can result in aberrant laser pulses during the capsulotomy creation. Also, in studies we reviewed in which the tear rate was high, we felt it was due to the amount of time required for the capsulotomy, so we reduced the two-second capsulotomy to 0.8 seconds. I think the combination of increased vertical spacing and the timing and quickness of the capsulotomy allowed us to decrease our tear rate.”

Nashville, Tenn., surgeon Ming Wang says that surgeons need to be aware that, since the femtosecond separates tissue by creating a series of microscopic bubbles joined by uncut tissue, the tissue might not be cut in all areas of the capsulorhexis. “You have to be careful when detaching the circular capsulorhexis cap from its peripheral rim,” he says. “If you’re not careful, you can produce radial tears if you don’t press it down in the center first.”

Incision Issues

Surgeons say one of the laser’s basic functions that gives the most headaches is the creation of the cataract entry wound and paracenteses.

“Creating the entry wound and a paracentesis is a well-recognized limitation of all femtolaser platforms,” says Dr. Yeoh. “What you see is not what you get. In other words, an incision placed at a certain location on the system’s screen actually appears in a slightly different location on the cornea itself. Certain laser platforms that use a variable aperture are better at delivering pulses to the corneal periphery so that incisions are usually patent and well-located, though. The surgeon should get used to his individual femtolaser machine in order to understand where the incisions end up, and factor this in when he chooses the incision location.”

Many surgeons just pull out the diamond blade when it’s time to make the entry wounds. “I’ve been very unimpressed with the laser’s ability to cut through peripheral opaque tissue [when making the initial incision],” avers Dr. Weinstock. “Most patients have some opacity or arcus to their limbus, right where you want to put the wound. And it’s kind of hit or miss as to whether someone has that, since you can’t really tell during the docking step because the visualization usually isn’t good enough to see that area in detail. So, quite a bit of the time, after trying the laser, I end up having to use the diamond blade anyway to complete the incision, which results in an irregular wound because I’m trying to find the track of the laser incision. Then, when I put the blade through that track I wind up getting false tracks and extra wounds. So, instead of the laser, I just use a diamond blade first so the wounds are in the exact same spot each time.”

Femto-fragmentation

Softening a nucleus and placing fault lines for subsequent separation during phaco is a feature of femto cataract surgery that helps surgeons cut down on the amount of ultrasound energy they have to use in the eye. There are ways to do it, however, that are safer or more effective than others, surgeons say.

|

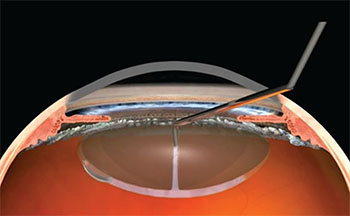

London’s Sheraz Daya, MD, developed a hydrodissection method that’s safer for femto-cataract: translenticular hydrodissection. In it, a chopper/cannula inserted into the mid-periphery of the nucleus gently injects fluid that displaces the posterior gas bubble (visible on the bottom left) and frees the lens from the lens capsule. |

London’s Dr. Daya says the laser configuration the surgeon chooses can help protect the ocular anatomy during phaco. “For hard lenses, I usually make two small rings in the center of the nucleus to get rid of the sharp edges,” he says. “If the pieces are sharp, if any of them were to go in a direction that I didn’t want—such as forward—it could cut the capsule. Soft lenses, on the other hand, are tricky because you can’t rotate them. They’re easy to take away once you’ve got a hold of them, but they stick to the capsular bag more.”

Dr. Wang says it pays to know how the laser interacts with tissue when fragmenting the nucleus. “How deep the laser can travel into the nucleus and remain effective depends on the density of the lens,” he explains. “The denser the lens, and the deeper the travel, the less efficient the femtosecond laser’s cavitation bubble will be in separating the tissue; shots are reduced in laser intensity when they reach the tissue that’s more posterior in a denser lens. This means your potential cut is even weaker on the backside of the lens. Understanding this is important to avoid having a false sense of security that all those cuts are truly separating the lens. Those rings and crosses may not actually be cut. So, with a denser cataract, after you’ve done the femto-fragmentation, you almost have to ignore that the lens has been pre-chopped. You’ll be safer this way because you’ll pay more attention to your manual maneuvers. If you’re too cavalier about it and just go in and assume those lines actually show tissue separation, you can break the capsule. Remember, the lines the laser creates are just lines of potential separation.”

Modified Hydrodissection

Due to either intracapsular gas created during femtosecond nuclear fragmentation or fusion between the cortex and anterior capsule—or a combination of both—surgeons avoid traditional hydrodissection when doing FLACS, since it can result in tears. The translenticular approach, developed by Dr. Daya, is a good alternative.

Dr. Daya’s approach is performed after femto-fragmentation. “I use a device I designed with B + L that looks like a phaco chopper but is actually a cannula,” he explains. “Using the instrument, I go through one of the fragmentation lines into the mid-periphery of the lens—where it’s softer—and gently inject fluid,” he explains. “I then look for a fluid wave and displacement of the posterior gas bubble. While I’m irrigating, I’ll turn the lens. When it rotates, then I know I’ve hydrodissected properly.” (See image, above)

Dr. Daya says this technique can be especially helpful with soft lenses. “Soft lenses are tricky because you can’t rotate them,” he says. “I’ve found that if I do a translenticular hydrodissection, I’ve got to get a nice push of fluid to prolapse that soft lens out of the bag. They’re tricky because they’re so sticky. I find a quick hydrodissection—a big pulse of fluid—helps dissect that kind of lens.”

Dr. Tauber says that, as an alternative in some easier lenses, pneumodissection using the trapped gas can be effective. “In pneumodissection, we gently tilt the lens—touching it at one of its lateral poles—and allow the gas that’s caught in the lens to escape,” he says. “That seems to allow the lens to spin freely in most cases.”

Other Pearls

Surgeons offer other bits of advice to improve the femtosecond laser’s performance in general and in unique situations.

• Power setting adjustments. Dr. Tauber says that doubling the laser’s energy output, usually from 4 to 8 µJ, in patients with a scar from herpes or from trauma, as well as in patients with a history of corneal surgery, allows for better penetration of the beam. “Also, increase the cut depth from 500 to 800 µm in a cornea with disease such as Fuchs’,” he says, “because the corneal disease can potentially limit the energy penetration.

“Another instance in which we’ll change the energy settings and depth is in patients in whom we place a capsular tension ring,” Dr. Tauber adds. “This is because these devices are implanted under viscoelastic and, no

matter how much viscoelastic we remove afterward, there’s always some left in the eye that can interfere with the laser. Increasing the energy in these patients makes the risk of an incomplete capsulotomy much less.”

• Intumescent cataract. These cataracts can be difficult due to the pressure that’s built up within the bag. When the anterior capsulotomy is created and this pressure is released, it can cause a radial tear. “These are a challenge,” says Dr. Tauber. “The faster the capsulotomy can be done, though, the less likely a problem will occur. One recommendation that’s been made is to put the femtosecond laser in the OR and make as small a capsulotomy as possible—around

2 mm. This allows the cortical material that’s built up a lot of pressure to leak out without affecting the capsule and giving the Argentinian flag sign. Then, come back to the laser, redock the patient and do a 4.9-mm capsulotomy. Tim Schultz, MD, in Germany has discussed this approach.3 However, this isn’t practical for many people because their lasers are most likely outside the OR. In that case, I think a smaller capsulotomy, maybe 4.5 mm, done in under a second would be helpful.”

• Laser maintenance. Dr. Wang is a PhD in laser physics, which he says makes him very aware of how well the laser is operating. “I built many lasers in graduate school,” he says. “And I know that a lot of laser components can be slightly altered over time and, as a result, cause the beam to have the wrong focus or intensity. We use the laser to burn a piece of plastic every day before starting our femtosecond cases, because inside the machine a mirror can be inadvertently tilted by bumping it, dust can accumulate, and so on. Also, the cavitation bubble spacing has to be correct, so you have to work with the laser company’s engineer in the beginning, and then periodically—such as every six months—to assess the bubble effectiveness. In addition, monitor the laser for a decrease in the quality of the cuts, which, by the way, is normal. If the energy falls below its threshold, you can’t keep operating. You’ve got to call in the engineer.”

Ultimately, Dr. Wang says femtosecond cataract lasers’ ability to produce good results, or complications, depends on how they’re used. “I think that, overall, this technology will drive us forward,” he says. “But, just like any powerful engine that drives you forward, remember that it can go backward, too.”

Dr. Weinstock has consulted for Alcon, AMO, Bausch + Lomb, Lensar and Omeros. Dr. Yeoh is on the speakers bureau for Alcon and AMO. Dr. Daya is a consultant for Bausch + Lomb. Dr. Tauber is a consultant for AMO. Dr. Wang has no financial interests in the products discussed. REVIEW

1. Nagy ZZ, Takacs AI, Filkorn T, et al. Complications of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014;40:1:20-8.

2. Yeoh R. Intraoperative miosis in femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014:40:5:852.

3. Schultz T, Dick HB. Laser-assisted mini-capsulotomy: A new technique for intumescent white cataracts. J Refract Surg 2014;30:11:742-5.