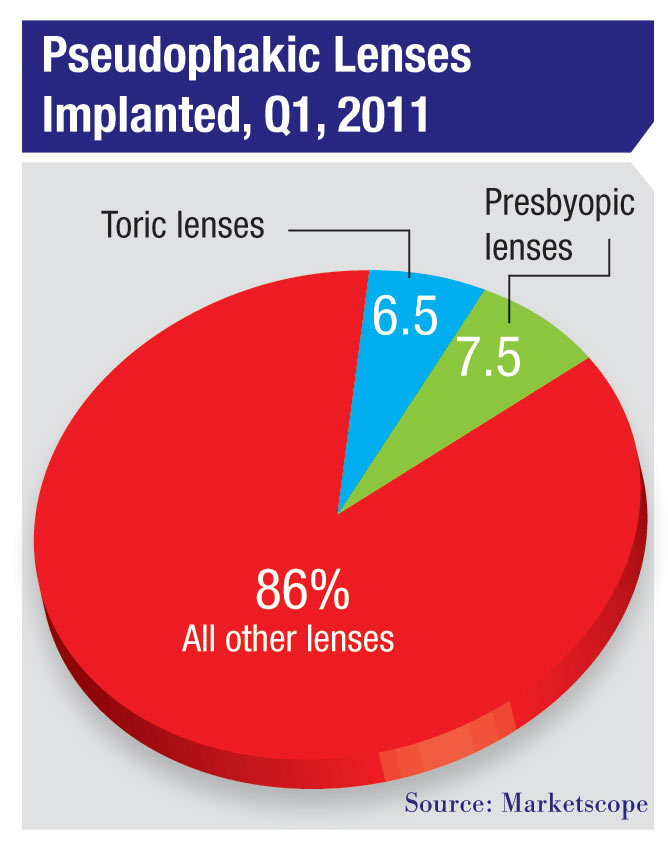

Recent data from Marketscope, based on survey responses from 347 U.S.

ophthalmologists in the first quarter of 2011, indicate that about 25

percent of surgeons don’t currently offer toric or presbyopic lenses,

and another 25 percent offer only the toric lenses. (Note that this

includes practices that only implant a small number each year.) In

terms of the lenses themselves, presbyopic lenses now make up about 7.5

percent of the IOLs being implanted; toric lenses represent about 6.5

percent of the total. While toric lens use has been increasing, the

number of presbyopic lenses being implanted hasn’t changed much in the

past two to three years.

Recent data from Marketscope, based on survey responses from 347 U.S.

ophthalmologists in the first quarter of 2011, indicate that about 25

percent of surgeons don’t currently offer toric or presbyopic lenses,

and another 25 percent offer only the toric lenses. (Note that this

includes practices that only implant a small number each year.) In

terms of the lenses themselves, presbyopic lenses now make up about 7.5

percent of the IOLs being implanted; toric lenses represent about 6.5

percent of the total. While toric lens use has been increasing, the

number of presbyopic lenses being implanted hasn’t changed much in the

past two to three years.

The adoption of new technologies tends to follow a curve, starting slowly, then picking up speed. John Pinto, president of ophthalmic practice management consulting firm J. Pinto & Associates, and the country’s most-published author on ophthalmology business and career management topics, points out that premium IOLs are still in the early adoption phase. “If you include toric lenses in the premium category, premium lenses make up about 14 percent of cataract implants today,” he says. “A typical surgeon tells me that at least 30 to 35 percent of his patients would probably do well with one of these lenses. That’s a very anecdotal number, but it suggests that only about half of the patients who might be optimally served by these lenses are receiving them.”

Clearly many patients benefit from having these lenses implanted, and practices certainly stand to benefit financially. But as any doctor with a high conversion rate can tell you, making a success of this requires changing the tone and character of your practice; changing the way you schedule patients; tracking your success in converting patients; getting your staff to add new skills to their repertoire; figuring out the best ways to position and price these lenses; and mastering a series of do’s and don’t’s when you, the surgeon, talk to the patient about these lenses. (It’s also true that some personality characteristics can have a positive or negative impact on your chances of success.) In short, a high practice conversion rate has to be earned.

Here, several physicians and industry experts offer their best advice on what to do—and what not to do—in order to increase your conversion rate (and produce happier patients).

Creating a Premium Practice

One of the key elements of generating a high conversion rate is providing potential premium lens patients with a “premium” experience. (Would you buy a Lexus from a dealer with a dirty lot who provides mediocre service?) Our panel offers these pearls for making patients more likely to invest in an upgrade:

|

• Don’t schedule different types of patients on the same day. “We don’t schedule any general clinic during days when we’re doing preop screening for cataract or LASIK,” says James C. Loden, MD, founder and president of Loden Vision Centers in Nashville, Tenn. “No dry-eye patients, no glaucoma, no corneal transplants. You don’t want someone who’s thinking about spending $2,800 on a lens sitting next to a wheelchair-bound patient on dialysis with neovascular glaucoma and an Ahmed shunt. The reality is, premium patients do not like sitting next to sick people. In addition, seeing sick patients undercuts your efficiency, and you can’t ask people to wait if they’re paying a premium price. So we schedule them on different days.”

• If you don’t have a refractive surgery laser, consider investing in one. “If you don’t have your own laser, you need to either add that to your repertoire or form a relationship with somebody,” notes Richard Boling, MD, who practices at Boling Vision Center in Elkhart, Ind. “It makes more sense to do the laser touch-up yourself, because forming a relationship with somebody else makes you unable to do it at a steeply discounted rate, which helps to keep your patients happy.” Despite the difficult economy, Dr. Boling’s practice has maintained a healthy conversion rate of about 25 to 30 percent. “That isn’t on a par with some practices,” he admits, “but it’s pretty good for a small, conservative community in an area that’s been hit relatively hard by economic woes over the past few years.”

• Present all the options to all patients. “We explain the options to all patients—even Medicaid patients,” says R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, La., and assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Tulane School of Medicine in New Orleans. “In fact, a few of our Medicaid patients have found the money to upgrade to premium IOLs.”

Dr. Loden agrees. “Never judge the patient by his insurance or personal appearance,” he advises. “It’s really surprising sometimes who is able and willing to pay for premium lenses. I’ve seen patients who looked like ditch diggers pay $5,000 cash per eye for refractive lensectomy. A patient may be an industrial laborer, but he could be the guy who owns the company. Also, I think there’s a legal and ethical side to this; I believe we’re obligated to present all the options to every patient who walks in the door.”

• Don’t bother advertising your premium options. “You already have an existing group of patients coming into the practice to have cataract surgery,” notes Mr. Pinto. “You’re taking an existing patient who’s definitely going to buy the basic package and moving him up to the next level. It’s not wrong to do a direct-to-consumer ad campaign about premium IOLs, but it’s probably more effective to have a generalized cataract promotion, or a senior vision-care promotion that brings in more patients. That gives you a bigger base of patients to talk to about the premium lenses.”

Dr. Loden says his practice found that external advertising and marketing of premium lenses didn’t generate enough revenue to pay for the advertising. “We tried it,” he says. “You can dramatically increase your numbers with marketing—but it won’t offset the cost of the marketing. On the other hand, training the staff and hiring a counselor will more than pay for the cost of doing so.”

• Track your conversion rate. “One hundred percent of my client practices track their conversion rates, and it’s essential,” notes Mr. Pinto. “The numbers should be tracked by provider as well as by the entire practice. Unless you have an accurate, up-to-date view of where you are compared to your peers and in terms of your practice goals, you’re reducing the odds of being able to reach those goals. Even if you’re doing two premium lenses a week out of 200 cases a month, and you’re still in the early stages of adopting this technology, if you have a goal of getting up to a 30-percent implant rate, you have to start somewhere.”

Dr. Loden agrees that it’s extremely important to track your conversion rate. “Our rate is 24 percent as of the first quarter this year,” he says. “Tracking your rate lets you know how successful your staff is in performing these services. It will also tell you the impact of something like staff training. However, you have to realize that your conversion rate will fluctuate from month to month. What you want to see is an average trend that stays fairly consistent.”

Dr. Boling says his practice’s tracking methodology makes it easy to see how they’re doing. “If we’re a little bit below our percentage goal, the number at the end of our tracking sheet for that month appears in red,” he says. “If it’s red, we go back and see what we need to do differently to get that goal accomplished. If it’s green, we met our goals.”

Practice Size: How Important?

Some practices may have an advantage when it comes to converting patients to premium lenses simply because of the size of the practice. For example, Mr. Pinto says it’s important to have sufficient overall cataract volume— ideally 40 or more cases per month. “In a typical setting you’re only going to have a 10 percent conversion rate or less at the outset,” he notes. “So unless you’re seeing four, five, six or seven of these patients per month, the pace at which you adopt is going to be permanently low, and your learning curve and confidence curve will be quite shallow.”

This may not be a deciding factor, however. Giulia Newton, head of global strategic marketing at Abbott Medical Optics, maker of the Tecnis and ReZoom multifocal IOLs, observes that success at converting patients often has more to do with a practice’s focusing on this as a goal than with the size of the practice. “We see practices with high volumes that excel at converting patients to premium lenses,” she says. “The entire practice is aligned with this goal—ensuring that the premium IOL patient is getting an experience and outcome that’s above and beyond general cataract surgery with a monofocal lens. At the same time, we see other high-volume practices that are not driven to adopt premium lenses to the same extent. They use a different practice model that emphasizes volume rather than presenting every option.

“The same is true for lower-volume practices,” she notes. “Some have decided to be premium practices and to focus all of their processes and people around that, and many are very successful at converting patients to a cataract refractive procedure. That’s been true even in economically hardhit areas where you’d think there was very little opportunity to charge patients for the refractive portion of their cataract surgery.”

Make the Most of Your Staff

As important as the surgeon is in converting patients, the staff must also be onboard. These strategies can help:

• Hire staff for attitude and intelligence. “We tend to hire based on attitude and intelligence and then train the person to be what we want them to be, instead of hiring somebody on the basis of background or experience,” says Dr. Boling. “Our surgical coordinator has energy, compassion, she’s nice to be around, she smiles easily, she’s positive. So we have the right person in the right place. To succeed, you need someone who is upbeat, knowledgeable, understands the kind of results that you’re getting as a practice, and then can convey those confidently to the patient.”

• Get your technicians talking. Dr. Loden notes that technicians can do a lot to help educate patients. “The technicians are doing the preop refractions, the preop IOLMaster, and—if the patient elects—the preop topography,” he notes. “Looking at the Ks on the IOLMaster, they can immediately see whether the patient has corneal astigmatism or not. If astigmatism is present, our technicians start discussing it with the patient. They talk about our astigmatism option, and the fact that uncorrected astigmatism negatively impacts all vsion ranges—distance, intermediate and near.”

• Consider hiring a special premium lens counselor. Dr. Loden believes having a special counselor for the premium lens options is necessary if a practice hopes to achieve a high conversion rate. “We have two full-time counselors for LASIK and premium cataract patients,” he explains. “We run our schedule so as to make sure we’re not overwhelming them, because the most important thing is to make sure premium patients don’t have to wait.”

However, Mr. Pinto says that whether hiring a special counselor makes sense depends on the size of the practice. “You need a cataract surgical counselor for about every 75 cataracts performed per month,” he explains. “That’s a typical, average ratio, although it’s different from one practice to another. If you have a practice with 75 cases a month, you’re not going to have two surgical counselors, one for the non-premium lenses and one for the premium ones; you’ll have one counselor trained to talk to both kinds of patients. If you have 150 cases per month, it would be reasonable to have two counselors, one of whom is a specialist; then, if a patient is sitting on the fence, he’ll see the specially trained counselor.”

• Don’t delegate the conversion to your support staff. “To be successful at this,” notes Mr. Pinto, “you need a well-educated, supervised and motivated support staff. However, as a success factor, your staff trails well behind all other aspects that are providermediated. It may be counter-intuitive, but if you say, ‘I’m the doctor, I really don’t want to be directive with the patients and put them into a corner about paying extra money … I’ll let my staff do that,’ this will not go well. It’s most effective if the conversion is accomplished by the surgeon, and then the surgical counselor just takes care of the paperwork and backs up the surgeon on the patient’s excellent choice.”

Get the Pricing Right

The two biggest issues here—aside from deciding the price itself—are avoiding overwhelming your patients with too many options, and deciding whether to include the cost of refractive touch-ups (which some percentage of premium patients will require) in the initial price, or charge for them only when they’re needed.

Dr. Loden observes that it’s possible to scare a patient off with too many options. “If you offer the patient an accommodative lens, a Re- STOR 3.0, a Tecnis multifocal, a toric STAAR lens, a toric Alcon lens, a monofocal spherical or aspheric lens, and then explain the difference between a touch-up with LASIK or PRK all in one session, the patient will be overwhelmed and have no clue what to do,” he says. “The best approach is to offer three clear-cut options.” Interestingly, he notes that patients generally won’t pick the lowest- price option. “They’ll pick the middle or the highest,” he says, “as long as they have the money or can do the financing.”

Following this model, Dr. Loden’s practice offers patients three options at different price levels. “Option one is a standard cataract surgery product where the patient receives an aspheric lens,” he says. “Option two, at $1,595 per eye, is our astigmatism correction program; this comes with a guarantee of legal-to-drive vision. Our top tier, option three, is our presbyopic product—either a Crystalens or Tecnis multifocal, for $2,895 per eye.

|

Mr. Pinto says most practices build any touch-ups into the initial

price. “Patients who need a touch-up won’t be jumping up and down with

joy anyway,” he notes. “You can say to the patient, ‘You’re one of the 5

percent of our patients who need a supplemental correction, as we

discussed before you had the surgery. The good news is, there’s no

additional cost; it’s built into the fee that you paid.’ ”

Dr. Boling’s practice, however, doesn’t include the cost of any possible postop correction in the initial price. “If we need to refine an outcome, we significantly discount our laser treatment because we believe in the process and we want happy patients,” he says. “We charge enough to cover our expenses and a tiny bit extra, and we haven’t had any bad reactions from patients. They can see that they’re getting the treatment at a huge discount relative to what a LASIK patient would pay.”

But some practices who have tried this approach have had unhappy results. “In the past we had lower prices that did not include a possible touch-up, as a way to provide the patient with a better value,” Dr. Loden explains. “We’d have patients sign a paper stating that they’d understand if they had to pay a discounted price for LASIK or PRK. The problem was that some patients were very angry when they needed a touch-up; we had patients accuse us of deliberately missing the IOL power in order to charge them for a second procedure. As a result, we changed our policy; now we include the cost in the price.”

The Personality Factor

Dr. Boling’s practice, however, doesn’t include the cost of any possible postop correction in the initial price. “If we need to refine an outcome, we significantly discount our laser treatment because we believe in the process and we want happy patients,” he says. “We charge enough to cover our expenses and a tiny bit extra, and we haven’t had any bad reactions from patients. They can see that they’re getting the treatment at a huge discount relative to what a LASIK patient would pay.”

But some practices who have tried this approach have had unhappy results. “In the past we had lower prices that did not include a possible touch-up, as a way to provide the patient with a better value,” Dr. Loden explains. “We’d have patients sign a paper stating that they’d understand if they had to pay a discounted price for LASIK or PRK. The problem was that some patients were very angry when they needed a touch-up; we had patients accuse us of deliberately missing the IOL power in order to charge them for a second procedure. As a result, we changed our policy; now we include the cost in the price.”

The Personality Factor

“Surgeons have a broad distribution of assertiveness levels,” notes Mr. Pinto. “That’s fine, but the reality is that the surgeons who are most successful at converting patients to advanced lenses tend to have an innate surgical assertiveness. These are the surgeons who say: ‘We have a problem, let’s fix it.’

“In fact, the best way to predict surgical assertiveness—and by association, the greatest success at converting patients—is by looking at a surgeon’s percentage of preoperative patients who are 20/40 or better when he decides to perform cataract surgery,” he continues. “Studies I’ve done have found that the average surgeon performs cataract surgery on patients about 50 percent of whom are 20/40 best-corrected acuity or better before a brightness acuity test. If a surgeon only has 20 or 25 percent of patients in that category, he’s waiting until vision is worse to operate, and he’s probably more conservative. That doesn’t make him a better or worse doctor; it simply makes him less assertive compared to his peers. This type of surgeon may find converting patients to premium lenses a more frustrating part of his practice.”

A second personality issue is sensitivity to criticism from picky patients. “To succeed with premium lenses,” observes Mr. Pinto, “you can’t be the kind of person who does 500 of these procedures, and when one patient complains you throw your hands up and say, ‘That’s it, I’m not going to do this anymore.’ Those types of individuals will have trouble incorporating these lenses into their practices.”

Saying the Right Thing

The surgeon’s importance in the conversion process can hardly be overstated, so how effectively the surgeon communicates with the patient is critical. Our experts offer these tips:

• Take steps to boost your faith in the lenses. “To get through the first six months or year of offering these lenses, the ophthalmologist needs to believe in the technology broadly, conceptually and empirically,” says Mr. Pinto. “Most ophthalmologists are highly ethical, and unless they believe they’re providing the best available product options, it’s just not going to ring true to the patient. The two best ways to gain confidence in these lenses are formal training for the doctor and interaction with respected colleagues who are boosters for the technology. There’s nothing like peer-to-peer testimonials to provide an inoculation of confidence.”

|

Dr. Wallace agrees. “If you emphasize the technology too much and the patient has a problem postop, the patient will blame the IOL and complain about it greatly and ask you to take it out,” he notes. “That’s a lot more trouble than just treating the patient for dry eye, which could be the reason he’s having trouble.”

• Uncover the patient’s needs and wishes. Although you have to do some of this face to face with the patient, you can get a partial idea of a patient’s needs and desires by having him fill out questionnaires at the beginning of his practice visit.

“In our practice, patients are required to fill out the Dell survey when they come in,” says Dr. Loden. (The Dell survey is a brief questionnaire that asks patients their preferences regarding their visual outcomes; this provides useful information for the surgeon, while making it clear to the patient that perfect vision at all distances, under all lighting conditions, isn’t possible.) “That allows me to quickly see whether it’s important to the patient to eliminate glasses. Next, we offer the patient a custom cataract evaluation that includes topography And wavefront analysis for $250 [bilateral]. If the patient doesn’t sign up for that, we’ve found it indicates an 80 percent or better chance that he won’t choose a premium IOL—especially if the Dell survey says he doesn’t care about eliminating glasses.”

Dr. Loden says the most important part of the patient interaction is him sitting down with the patient to clarify the patient’s wishes and desires. “I ask the patient whether it’s important for him to not wear glasses after the cataract surgery,” he continues. “If he says, ‘I’m fine wearing glasses,’ I say, ‘Do you understand that with two diopters of astigmatism you’re going to have to wear glasses for distance, intermediate and near vision? Are you okay with that?’ If he says yes, he goes on to surgery scheduling. If he says, ‘No, I didn’t realize that,’ then we go into more discussion. If the patient says, ‘I don’t want to wear any glasses at all,’ we go into discussion of monovision vs. multifocal lenses vs. accommodative lenses. I lay a little bit of the groundwork; then the patient goes to my refractive surgery staff. They go over the product in detail—the pricing, the financing, the logistics, and the risks and benefits of the lenses, compared to standard lenses. If the patient has any questions that require my expertise, I come back in and meet with the patient to address them.”

• Present side effects as positive signs. One key aspect of good salesmanship is being able to frame potential disadvantages as something positive. Dr. Boling has succeeded in doing that with one of the most common downsides of multifocal lenses. “When I get done with the surgery,” he says, “I take off the drape and say, ‘Everything went perfectly. Hopefully, tonight you’ll start seeing little ringlets around lights. That’s a good sign—it means the lens is working.’ That statement sets the tone. Sometimes a patient will come in the next day and say, ‘I saw those ringlets last night!’ I say, ‘Good!’ I’m setting it as a positive instead of a negative. It may sound a little cheesy, but it does help.

“Of course,” Dr. Boling adds, “I also explain the process of neuroadaptation, and I tell the patient that the lenses will work better at three months than they will at three weeks, and even better at six months.”

• Show just the right amount of enthusiasm. “The surgeon needs to present the appropriate premium lens option with an enthusiasm that gets the patient excited about it, as opposed to a more dry, academic, conservative presentation,” says Mr. Pinto. “At the same time, you can’t swing all the way to the other end of the continuum and be an unabashed booster of a lens—that will sound as if you’re trying to put something over on the patient.”

Dr. Loden emphasizes that a practice should avoid pushing people to opt for something they can’t afford. “I think it’s very important to explain to patients that a standard lens implant will give them great vision,” he says. “It’s just that we can’t guarantee that they’re not going to wear glasses. In fact, we can pretty much guarantee that they will have to wear glasses, at least some of the time. But they’ll see just as well with a pair of glasses as they would with one of our premium upgrades. I don’t want people to think they’re getting an inferior product if they turn down the upgrade.”

• Use the right word choice. “When you talk to your patients about these lenses, small nuances in what you say can make a real difference,” notes Mr. Pinto. “For example, you could say to the patient, ‘We can offer you the standard lens or the more costly premium lens.’ Or you could say: ‘We can offer you the basic lens or the high-definition, high-tech lens. Which would you like?’ One choice of words is more likely to evoke a favorable response than the other.”

• Remember that actions speak louder than words. Dr. Boling has had good experiences with the ReSTOR lens, and says his resulting enthusiasm helps to motivate patients. “I put bilateral ReSTOR’s in my mom about four years ago,” he notes. “She hasn’t worn glasses since. My dad, who’s been in practice for 50 years also had them implanted.

I’ve put them in a lot of friends and family. They’re not without peril, but they work so well that I’m enthusiastic about them. Patients pick up on that.”

• Don’t combine motivation and informed consent talks. “Sometimes,” Mr. Pinto points out, “a doctor will say something like, ‘You know, this advanced lens would really be a good choice in your case. Of course, it doesn’t work for all patients, and there are potential complications, including blinding complications, that could occur. However, in your case I’m sure those won’t occur.’ The doctor goes back and forth between what is really meant to be a motivational talk and an informed consent talk, with poor results. Instead, take it one step at a time. First, have the motivating discussion with the patient; let him know what you believe is the best choice for him. Once he agrees with your approach, then, and only then, should you switch gears and proceed with the informed consent.”

Mr. Pinto notes that surgeons have a wide range of opinions about the appropriate degree of assertiveness. “Mainly,” he says, “it’s important to be aware of this issue and choose your words accordingly.”

• Set appropriate patient expectations. “I try to set expectation levels early on regarding what the premium lenses can accomplish,” says Dr. Boling. “Certainly you want to say, ‘These are great lenses, but they’re not like the ones God gave you; they won’t be infinitely adjustable from distance to near. However, they are a quantum leap from what we could do a few years ago.’

Dr. Wallace makes sure multifocal patients expect a period of adjustment postop. “They need to understand that this is a new vision system,” he says. “I explain that it takes time for the brain to understand how to use it. I’ve seen patients get frustrated and decide that they’re just ‘not good at this,’ when the reality is they’re just getting used to something new.”

Dr. Boling adds that it’s important to identify individuals who have unreasonable expectations or too-high visual demands. “To those folks, I say, ‘I don’t think I can meet the kind of expectations you have.’ Once you take the premium option away, they tend to rethink what it is they’re after,” he says. “Of course, even if your comment causes a patient to rethink his demands, you may not want to operate on this type of patient.”

• Be prepared to respond to resistance. “Resistance to upgrading comes in three major categories: First, the cost; second, concern about results—‘Is this going to work for me, doctor?’; and third, concern about the theoretical hazards of being subjected to not-yet-fully vetted technology,” says Mr. Pinto. “You need to have very sincere, effective answers to these concerns.”

It All Comes Down to...

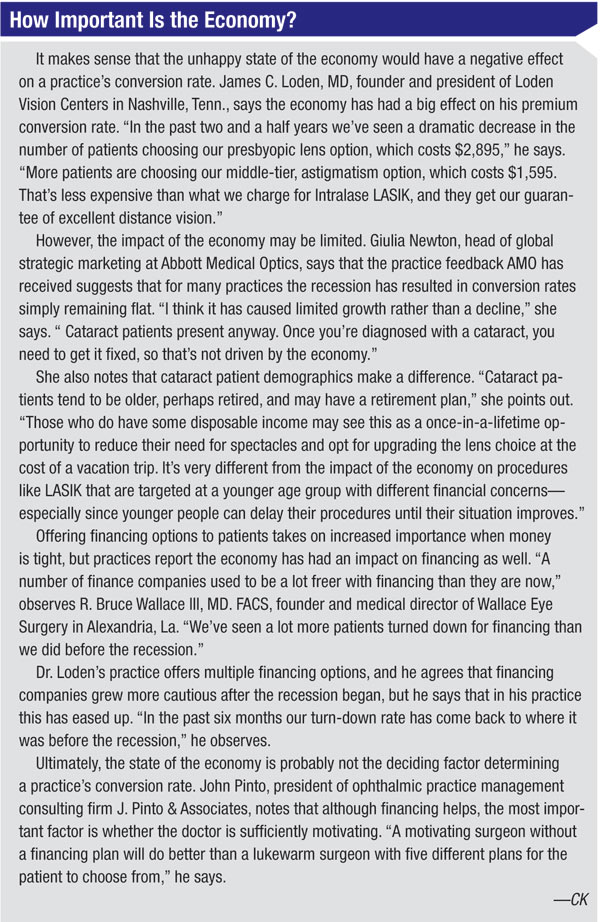

Despite the condition of the economy, it appears that achieving a significant conversion rate is indeed possible for most cataract practices—if they’re willing to put in the time and effort necessary to provide patients with the right kind of experience, and willing to learn somewhat different ways of interacting with these patients. Most important of all, the doctor has to believe in the technology so that patients pick up on his or her enthusiasm.

“I have clients in areas very hard hit by the economic downturn who still have a substantial conversion rate,” notes Mr. Pinto. “It keeps coming back to the doctor. If the doctor is not sufficiently motivating, you’re never going to get very high conversion rates even in a strong economy. Everything else is a trailing factor. The doctor has to believe in this technology, and say what he believes to the patient.”

|

|