Given this patient’s clinical history and examination, leukemic retinopathy was the leading diagnosis. Leukemic retinopathy can manifest with a spectrum of features ranging from multifocal retinal hemorrhages secondary to underlying blood dycrasias to frank leukemic infiltration of the ocular tissues. Other diagnostic considerations included predominantly retinovascular disorders such as diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, ocular ischemic syndrome and retinal venous occlusive disease.

Given the funduscopic findings, a detailed history was completed revealing fevers, night sweats, weight loss and shortness of breath. Vital signs were obtained and found to be within normal limits: blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg; a heart rate of 73 beats per minute and a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

|

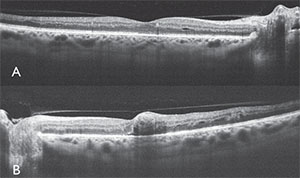

| Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography of the right (A) and left (B) eyes revealing focal retinal opacification and trace edema in the right eye, and retinal distortion with foveal blunting from deep retinal hemorrhage in the left eye. There was no evidence of choroidal infiltration at this time. |

Laboratory evaluation included a recent complete blood count with differential indicating the leukemic profile, normal blood glucose and elevated hemoglobin A1C of 7.4 percent (normal: 4 to 5.6 percent).

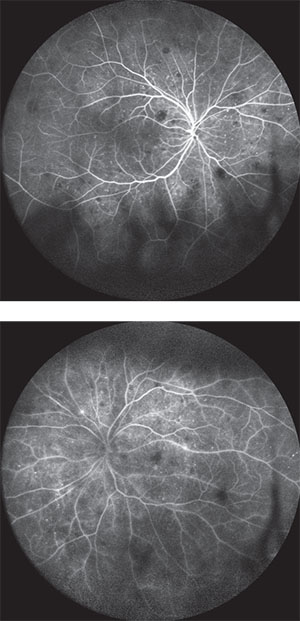

Further ophthalmic evaluation of our patient included spectral-domain optical coherence tomography to investigate the macular anatomy. In both eyes, OCT revealed intraretinal optically dense thickening in the nerve fiber layer, representing nerve fiber layer infarction and swelling. Additionally, there were multilayer focal densities consistent with intraretinal hemorrhage. The fovea OD revealed slight opacification, edema and minor cystoid changes, whereas the fovea OS showed blunted contour and mild edema from deep retinal density suggestive of blood (See Figure 2). There was no subretinal fluid. Fluorescein angiography demonstrated intact vascular filling with numerous areas of hypofluorescence corresponding to hemorrhage and nerve fiber layer infarction. There were extensive pinpoint areas of hyperfluorescence in all quadrants of both eyes. Mild retinal vascular staining was noted in the late frames (See Figure 3).

These findings were suggestive of leukemic retinopathy. The patient was followed while on chemotherapy to document the resolution of fundus features.

Discussion

Leukemia is a malignancy characterized by a proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. This malignancy is classified as either acute or chronic based on whether the tumor cells are predominantly immature blast cells or well-differentiated mature leukocytes. Leukemia can affect any structure in the eye through primary infiltration or, more commonly, through secondary changes. The retina is the most commonly involved tissue of the eye in patients with leukemia.1

Secondary retinal vascular changes can result from systemic abnormalities in the setting of leukemia, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperviscocity and immunosuppression. In these cases, there can be evidence of vascular dilation and tortuosity, hemorrhage, ischemia or a combination of these features.2 Common clinically recognizable retinal signs of leukemia include:

• retinal or vitreous hemorrhage;

• microaneurysms;

• nerve fiber layer infarctions;

• peripheral neovascularization;

• vascular occlusion;

• venous tortuosity;

• perivascular infiltration;

• macular edema;

• retinal detachment; and

• retinitis secondary to infection.2,3

As these findings are largely non-specific, in the absence of a documented clinical history of malignancy, it’s possible to mistake ophthalmic signs of leukemia for other common disease entities, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus or other vascular diseases.4,5 This was the case for our patient, whose funduscopic picture was initially mischaracterized as diabetic retinopathy by the primary caregiver before the retinal findings progressed in severity and before leukemia was documented.

|

| Figure 3. Fluorescein angiography of the right (top) and left (bottom) eyes showing scattered hypofluorescence from retinal hemorrhages and nerve fiber layer infarctions, hyperfluorescence from pinpoint leaks in the retina and mild vascular staining. |

While improvements in chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment techniques for leukemia have made primary retina and choroid involvement quite rare, patients with acute leukemia may still manifest infiltration through the retinal arteries and veins, as well as in the choroidal vasculature. In fact, in autopsy specimens, the choroid is the most common ocular structure infiltrated with leukemic cells.6

A number of studies have evaluated the prevalence of ophthalmic signs in patients with leukemia at the time of diagnosis. In a study by Prof. Nicholas Jackson and colleagues, 63 newly diagnosed patients with acute leukemia were examined funduscopically and 33 (52 percent) were found to have at least one of the following findings: intra-retinal hemorrhage; white-centered hemorrhage; nerve fiber layer infarction; or macular hemorrhage. There was no association of the retinal findings with the severity of leukemic diagnosis, although there was an association with a higher white blood cell count.7 In a prospective evaluation of 120 patients with newly diagnosed adult and pediatric leukemia, Andrew P. Schachat, MD, and colleagues found similar secondary findings of leukemia in 47 patients (39 percent) and primary leukemic infiltrates in four patients (3 percent).1 James Karesh, MD, and colleagues conducted a two-year prospective study of 53 patients with acute myeloid leukemia wherein 34 patients (64 percent) were found to have retinal hemorrhages or nerve fiber layer infarctions. In their study, there was no association with age, sex or severity of disease, although there was a correlation with thrombocytopenia. During the follow-up period, no association was found between fundoscopic changes and treatment response. Interestingly, all patients who survived the induction phase of chemotherapy experienced complete resolution of all ocular findings.8

In our patient, the development of white-centered hemorrhages, frequently termed “Roth spots,” is strongly suggestive of a systemic disorder. Once thought to be hemorrhages associated with septic emboli, WCH are now thought to be non-specific intraretinal hemorrhages with a white center of various compositions, most frequently fibrin deposition at a site of acute retinal capillary rupture.3 They can be seen in numerous other conditions including connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, hypertension, anemia, trauma, disseminated fungal or bacterial infection, environmental toxicity and leukemia.9 WCH can be rarely found with diabetic mellitus, but this would be unusual and might be expected only with a dramatic increase in glucose rather than the typical indolent progressive process of diabetic vascular change.10

In conclusion, leukemia can affect any segment of the eye either through primary or secondary involvement. Leukemic retinopathy is the most common ophthalmic manifestation of the disease and is frequently seen in patients with active leukemia. In numerous publications, retinal hemorrhage from thrombocytopenia and nerve fiber layer infarction from anemia and leukostasis can be identified, although the presence of retinal changes does not appear to correlate with prognosis or disease severity. Due to the non-specific retinovascular manifestations in this disorder, in the absence of an established diagnosis of leukemia, the findings can be mistaken for signs of more common processes like hypertensive or diabetic retinopathy. If you notice a sudden change in the severity of funduscopic appearance, or findings out of proportion to the severity of the patient’s other systemic processes, this should prompt a detailed review of systems and appropriate laboratory evaluation. REVIEW

1. Schachat AP, Markowitz JA, Guyer DR, Burke PJ, Karp JE, Graham ML. Ophthalmic manifestations of leukemia. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107:5:697-700.

2. Sharma T, Grewal J, Gupta S, Murray PI. Ophthalmic manifestations of acute leukaemias: The ophthalmologist’s role. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:7:663-672. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701308 [doi].

3. Kincaid MC, Green WR. Ocular and orbital involvement in leukemia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1983;27:4:211-232. doi: 0039-6257(83)90123-6 [pii].

4. Raynor MK, Clover A, Luff AJ. Leukaemia manifesting as uncontrollable proliferative retinopathy in a diabetic. Eye (Lond). 2000;14:Pt 3A:400-401. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.102 [doi].

5. Tong P, Ozaki R. Roth spots in diabetes mellitus. Lancet 2003;361:9358:689. doi: S0140-6736(03)12568-8 [pii].

6. Brown GC, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ, Serota FT, Koch P. Leukemic optic neuropathy. Int Ophthalmol 1981;3:2:111-116.

7. Jackson N, Reddy SC, Hishamuddin M, Low HC. Retinal findings in adult leukaemia: Correlation with leukocytosis. Clin Lab Haematol 1996;18:2:105-109.

8. Karesh JW, Goldman EJ, Reck K, Kelman SE, Lee EJ, Schiffer CA. A prospective ophthalmic evaluation of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Correlation of ocular and hematologic findings. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:10:1528-1532.

9. Lepore FE. Roth’s spots in leukemic retinopathy. N Engl J Med 1995;332:5:335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502023320516 [doi].

10. Zaidi FH. Roth spots obscure the picture. Lancet. 2003;361:9374::2086; author reply 2086. doi: S0140-6736:03:13664-1[pii].