Today, however, as surgeons become more familiar with these options and more of them make it through the Food and Drug Administration approval process, a new possibility is arising: Increase the pressure-lowering power of these procedures by multiplying them. That can be done in two ways: in the case of a given device, by implanting more than one; and in general, by combining different MIGS approaches—in particular those affecting different mechanisms and pathways.

Using Multiple Pathways

The options we have for maximizing the effectiveness of MIGS procedures in many ways parallel what we can do with pharmaceuticals. For example, we can aim to lower IOP by maximizing a single outflow pathway using multiple drugs that affect that pathway, or by using two aqueous suppressants such as beta-blockers and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. I think this is much like placing multiple iStents in the trabecular meshwork, which the data suggests lowers pressure more than a single stent.

On the other hand, a lot of what we do with drugs involves lowering pressure by enhancing multiple pathways. We can lower pressure by decreasing aqueous production, but we also have drugs that enhance uveoscleral outflow, such as prostaglandins, and some newer drugs under investigation like rho kinase inhibitors and adenosine agonists that enhance trabecular outflow. (Another new drug, latanoprostene bunod, has a complex molecule that affects both trabecular outflow and uveoscleral outflow.) Experience has confirmed that combining drugs that act on different pathways can increase the amount of pressure reduction, so acting via multiple mechanisms is a reasonable approach.

|

Which Combination to Use?

One question this raises is whether one particular combination of procedures (and/or outflow pathways) would be more effective at reducing IOP than another. Of course, we have no clinical trial data on which to base such a comparison right now, but even if clinical trials eventually compare different combinations of MIGS procedures, the results might not tell us which combination would work best in a specific patient. This is certainly true for drugs; if a trial compared a fixed combination of a beta blocker and prostaglandin to a beta blocker-brimonidine combination, you might get a bigger average drop in one group than the other, but an individual patient might not mirror that finding. So a trial wouldn’t necessarily tell you which choice is best for the patient seated in front of you.

The nature of the glaucoma, the age of the patient, the stage of the disease, how elevated the pressure is—all of these factors, and possibly others, may determine which combination of procedures will work best for a given individual. You might choose a different combination of MIGS procedures for a patient who has a relatively low IOP but is progressing than for someone with high-tension glaucoma, just because it makes more sense based on the pathophysiology of the disease. With glaucoma drugs (for now, at least) it’s trial and error because of the difficulty of predicting the efficacy of a given treatment. And that will probably also be true when combining MIGS procedures.

Of course, another factor that will affect which combination a given surgeon might end up using is the surgeon’s own preference and comfort level, as well as which techniques he or she happens to learn. If all the options were approved, some surgeons might feel most comfortable combining a Xen Gel implant and a Hydrus. Others might prefer combining ECP and Trabectome, or prefer combining the iStent Inject and the Supra. So which procedures a surgeon ends up using will be partly determined by the patient’s condition and partly by the surgeon’s knowledge and comfort level.

More of a Burden?

What about the burden that performing multiple procedures places on the surgeon and the eye? This really is the infancy of our use of MIGS procedures, but in comparison to other traditional procedures for lowering intraocular pressure these procedures are generally easier on both the surgeon and the eye—even if we do two of them. Most of these procedures can be done through the same single incision; there’s no need to make a second incision (except in some ECP cases). You go in with one instrument and place one type of stent; you come back out and go back in through the same incision and put a different stent in a different part of the anatomy. In the case of ECP, you use the same incision (and possibly a second one) to put the probe into the eye and apply the laser. I believe this compares quite favorably to trabeculectomy and tube shunt procedures in terms of complexity, time spent and trauma to the eye.

The other reality is that the amount of foreign material being implanted in the eye in MIGS procedures is miniscule compared to something like a tube shunt (or for that matter an intraocular lens), even if you implant multiple stents. Of course, they are utilized for different purposes and they’re placed in different parts of the eye, but the comparison is worth noting. (The downside of the small amount of material implanted in MIGS procedures is that the success of most of them requires a great deal of finesse in terms of understanding the anatomy of the eye and the proper placement of these devices.)

Building the Foundation

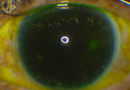

For now, we’re refining the use of the existing devices to maximize their individual effectiveness. For example, the work done with the iStent by Ike Ahmed, MD, suggests that the success of iStent surgery may be linked to determining the location of the most functional collector channels before placing the iStent.

We’re also learning about conditions that contraindicate specific MIGS approaches. For example, patients who have Sturge-Weber syndrome with a facial hemangioma typically have elevated episcleral venous pressure, countering aqueous outflow. If the episcleral venous pressure is 30 mmHg instead of the normal 10 mmHg, you’re not going to get a pressure reduction by clearing out the resistance in the trabecular meshwork with a stent or Trabectome. Instead, the surgeon might want to favor other pathways, such as using a Xen Gel Stent to generate subconjunctival filtration or reducing aqueous production with ECP.

In the meantime, trabeculectomy and tube shunts remain valuable surgical options. But I believe MIGS procedures will increasingly be considered in certain patients—whether it’s a single MIGS approach, or a combination approach—to eliminate the need for resorting to a trabeculectomy, or at least delay that need. The reality is that when managing glaucoma, we’re always trying to postpone progression with medications, lasers or surgery; we never cure the disease. So the more time and options we can offer to patients with safer procedures, the better.

A Great Opportunity

Of course, we’re just beginning to figure out which MIGS approaches will make the most sense for each patient. Not all of the devices out there will be approved, but hopefully many of them will be, and new modifications and options will be developed. If we have an arsenal of choices, a lot of surgeons will be applying them, perhaps in various combinations. Future development will be guided by people who are very clever who understand the basic science and the pathophysiology of the various diseases that we refer to as glaucoma.

And that’s a reason to be hopeful about the future. The glaucoma microsurgical arena is quite inspiring, and there are a lot of creative people still in their training or in their early years of practice who will make great contributions. We haven’t seen a situation like this in a while, where there are so many different possibilities and avenues an individual can take to make a great idea even better. It’s a wonderful growth opportunity for bright young people to radically change how we approach surgery for this disease, improving techniques and devices and setting more specific guidelines that better individualize care for patients, getting better outcomes and finding ways to minimize the risks. I firmly believe that over the next decade there will be really important contributions from bright young physicians, scientists who are excited about entering this field. REVIEW

Dr. Katz is the director of the Glaucoma Service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. He is a medical monitor and investigator for Glaukos and a medical investigator for InnFocus. Dr. Radcliffe is director of the Glaucoma Service and clinical assistant professor at New York University. He is a consultant for Glaukos, Transcend, Alcon and Allergan.

1. Augustinu CJ, Zeyen T. The effect of phacoemulsification and combined phaco/glaucoma procedures on the intraocular pressure in open-angle glaucoma. A review of the literature. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 2012;320:51-66.

2. Samuelson TW, et al. Randomized evaluation of the trabecular micro-bypass stent with phacoemulsification in patients with glaucoma and cataract. Ophthalmology 2011;118:459-467.

3. Kahook MY, Lathrop KL, Noecker RJ. One-site versus two-site endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation. J Glaucoma 2007;16:

527-530.