Here, three experts who help doctors to manage stress share 10 specific things you can do to stay afloat in a sea of stresses that seem beyond your control.

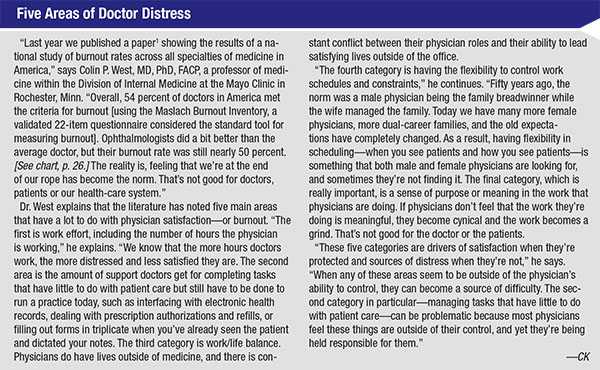

Be realistic about what you can control. While problems beyond our control can be stressful, attempting to control them anyway can make the situation far worse. “Trying to control things that are actually beyond your control is not a meaningful use of energy,” says Colin P. West, MD, PhD, FACP, a professor of medicine within the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn. Dr. West has spent many years studying the sources of physician satisfaction and burnout and the ways in which physicians can deal with the stresses of practicing today. “This is an important point, because physicians sometimes believe they should be controlling things that are completely outside their ability to control. That creates totally unnecessary extra stress.

|

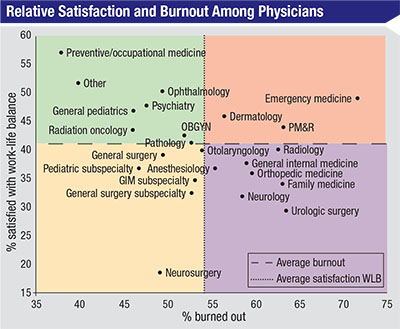

| A 2015 study of physician burnout and satisfaction1 found a 10-percent increase in the prevalence of burnout between 2011 and 2014, as well as a substantial erosion of satisfaction with work-life balance, despite no increase in the median number of hours worked per week. More than half of the physicians surveyed reported symptoms of burnout. Notably, ophthalmologists scored better on both continuums than most other specialties. (GIM=general internal medicine; OBGYN=obstetrics and gynecology; PM&R=physical medicine and rehabilitation.) |

“Sometimes this is an extension of perfectionism, a tendency to be a bit obsessive that many physicians exhibit,” he continues. “There’s a good side to that; it promotes professionalism and thoroughness. But there’s a dark side to it as well, if things get out of balance. When a physician is constantly overextending himself or herself, sometimes with the best of intentions, that can become dangerous for both the doctor and the patients.”

“We all face the challenge of dealing with things in life that are stressful, even distressing, because they’re beyond our control,” notes Craig N. Piso, PhD, a psychologist and organizational development consultant with a focus in ophthalmology, author of the book Healthy Power. “It may sound like a cliché, but there’s a lot of wisdom in the Serenity Prayer. The prayer says, ‘Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.’ The ideas in the prayer are a little simplified, but there’s a tremendous liberating power that comes with practicing all three parts of the prayer effectively. For example, if you don’t accept that some things are beyond your ability to change, you’ll be fighting battles you cannot win and you’re going to waste a lot of time and energy.”

Matthew J. Goodman, MD, an associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Virginia and a senior instructor in the Mindfulness Center at the University, where he teaches a course in mindfulness for health-care providers, notes that one of the most useful ways of thinking about the things that are (or are not) within our ability to control can be found in Stephen R. Covey’s well-known book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. “In that book there’s a chart depicting the areas over which we do or do not have control as a set of concentric circles, forming a kind of bull’s-eye,” he explains. “The ‘circle of control’ is the center of the bull’s-eye; around that is the ‘circle of influence.’ The largest circle is the ‘circle of concern.’ The circle of concern includes all of the things that we care about, which might include things like global warming, politics and family health. The circle of influence contains the smaller number of things that we have influence over—some amount of control. The center circle includes the few things we truly control, such as our own actions.

“When people get overwhelmed, sometimes they get those circles confused,” he continues. “When that happens, they feel like they’re responsible for—and need to take care of—things that are outside their circle of control. One result of that confusion is that you expend too much energy on issues that fall outside of your circles of influence and control, limiting the energy you have left to use on issues that you can truly impact. I like to play soccer, and many times I see players cursing about something that just happened, and they miss the fact that the ball just landed at their feet. If we’re too busy either cursing or crying, we miss the opportunities that present themselves.”

|

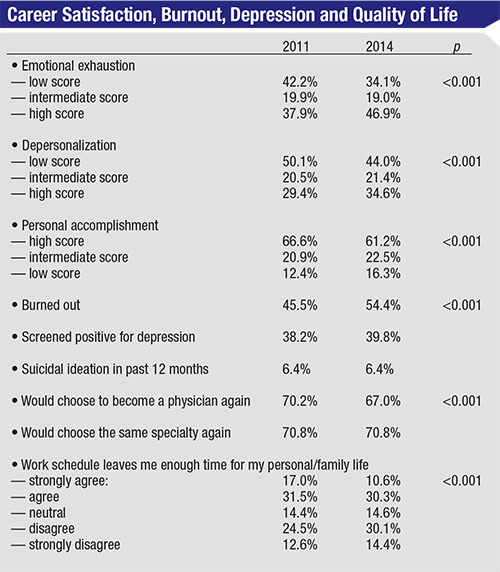

| In a 2015 study of physician burnout,1 U.S. physicians reported increased dissatisfaction and lessened quality of life in 2014 compared to 2011. (The first three categories listed above were assessed using the full Maslach Burnout Inventory; the burned-out percentages noted in the fourth bullet point were based on having a high score on either the emotional exhaustion or depersonalization subscales of the MBI.) |

“For example, one of the things that can be frustrating for a doctor is that patients don’t always do what we tell them to,” he continues. “If you take that on, and say, ‘Oh my god, this patient needs to be doing this,’ you can end up feeling really angry because the patient is undermining your efforts. Of course, the patient is really undermining his own health. If you want to have peace of mind, you need to accept the reality that we can’t control everything.”

Remember that you can accept unpleasant realities without approving of them. “I don’t mean to sound cold or patronizing, but if you really can’t do anything to change a situation, then the best strategy is acceptance,” says Dr. Piso. “The important thing is to remember that acceptance is not the same as approval. I can acknowledge that a situation is wrong or unfair; I can say that I don’t approve of it, that it needs to change and that I’ll change it if I can. But if I recognize that the situation is beyond my ability to change, at least for now, the healthy response is to let it go.

“The bottom line here is, what behavior is effective rather than ineffective?” he continues. “This is really about what works and what doesn’t work. If you knock your head against the wall, you’ll just experience pain and exhaustion. Instead, shift your focus away from those battles that you can’t win. Once you let go of those things through acceptance—not approval, but acceptance—then you’ll be free to devote your psychological and emotional bandwidth to those situations where you can make a difference, where you can be effective, where you can reach your goals. That’s empowering.”

Don’t be sucked in by the emotional payoffs that accompany commiseration. Dr. Piso notes that there can be emotional rewards for being stuck in a negative focus. “People sometimes feel that complaining and venting and recruiting others to join them in their unhappiness will help to solve a problem,” he says. “At some level they believe that if they get enough people to agree that this is wrong, then somehow by osmosis it will be remedied—that there will be enough sympathy, enough shared anger and pooled energy that somehow it will make a difference. Well, it’s good to know that others agree with you, but beyond having validation of your position and opinion—which might be entirely justifiable—nothing is really going to change.”

Make a conscious effort to choose a positive, productive focus. Dr. Piso notes that there’s an important principle behind this advice. “What we focus upon tends to expand,” he says. “That means that whatever it is you’re looking at, directing your attention toward, focusing your thoughts on or otherwise coordinating your energies and efforts toward, that thing will become more important to you. It will take up more space in your world.

“If you’re focusing on a good thing, something that makes you feel better and promotes goal attainment and wellbeing, that’s great,” he continues. “That positive focus will expand. Unfortunately, more often than not, people get stuck in a negative focus, often relating to problems and issues that can’t be changed through their effort. As that focus expands, it becomes more negative and more of a distraction, undercutting productivity, dissipating energy, derailing activities that could be more productive and increasing the likelihood that the individuals will become stuck in it. They can easily end up wallowing in misery.

“The way out of this trap is to make a conscious, intentional effort to shift your focus,” he concludes. “Make the choice to shift away from an unproductive, exhausting, even counterproductive focus on what’s wrong or cannot be changed, to those areas where a positive focus will have a chance to expand.”

Just because something seems beyond your control doesn’t mean it is. Sometimes things that seem beyond our control are actually within our sphere of influence, but over time we’ve come to accept them as an unchangeable “fact of life.” If you take the time to look more closely at something that you’ve accepted as being beyond your control, you may find that you have some control over it after all. “Sometimes it’s just a matter of sitting down and taking the time to assess your values and priorities,” notes Dr. West. “That simple act can help you rebalance things.”

Beware of holding a grudge against the perceived source of your problem. “There’s a teaching about this,” says Dr. Goodman. “Holding a grudge—in this case, being angry at the powers that be—is like taking poison and hoping the other person will get sick. If we spend time throwing things at the wall in the office, saying, ‘Those damn people keep cutting my reimbursement, who the hell are they?’ It doesn’t hurt them very much. But it does make us ineffective, stressed-out and crazy. If you catch yourself doing this, stop and direct your mental energy in other, more productive directions.”

Don’t make things seem worse by “disasterizing.” “When life isn’t the way we’d like it to be,” says Dr. Piso, “who do you think is better off: the person whose perspective emphasizes reasons to be hopeful and focuses on the positives that are there, as opposed to what’s missing; or the person who focuses on the potential for disaster? People often engage in a kind of mental movie-making where they’ll say, ‘Based on what’s happening today, you can only imagine where we’re going to be in six to 12 months.’ And then they start forecasting and predicting how bad it’s going to be. If you buy into what they’re saying, you’re going to experience more emotional distress. They may or may not be correct about the future, but that perspective is not uplifting or energizing or motivating. That’s why it’s so important to maintain a positive perspective.”

Dr. Goodman agrees. “It’s easy to exacerbate stress with your internal dialogue,” he says. “For example, I might think, ‘Boy, things are tough right now and I have to make some difficult decisions.’ That’s stressful. But if I add, ‘Oh my god, I can’t believe they’re making me do this, I hate this, I didn’t sign up for this,’ my internal dialogue will generate a lot of extra negative energy and power. It will add significantly to my stress.”

Dr. Goodman notes that the additional stress increases the likelihood that you’ll activate your sympathetic nervous system. “That’s good for fight-or-flight situations,” he says, “but it tends to undercut your ability to make good decisions. If you understand this, you can catch yourself when your internal dialogue gets very negative and move it in a different, more constructive direction.”

Learn techniques that can enhance your influence. As already noted, between the things we can truly control and those things beyond our reach lie many things that we can influence to some extent. Becoming more strategic about using our influence in areas such as patient behavior can help to lower our stress level.

“In our classes we teach a technique called motivational interviewing, described in the book of the same name by William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick,” says Dr. Goodman. “When patients are doing something that we perceive as not being in their own best interests, rather than arguing with them or berating them about it, it’s more effective to use empathy and understanding to hear where they’re coming from, to understand their ambivalence and help them move towards changing.

“This is beneficial in two ways,” he continues. “First, it reminds us that we’re not in the driver’s seat. It can be very frustrating and painful to try to control someone else’s behavior, because it doesn’t really work. Second, your influence actually increases once you give up the idea of controlling the patient. That’s because when people are not behaving in their own best interest they tend to be ambivalent and have what’s called the ‘righting reflex,’ an oppositional response elicited by advice. If I’m yelling at someone, saying, ‘You’ve got to take this medicine,’ but the patient is ambivalent about it, he’s going to push back. He’ll say, ‘Yes, but…’ and he’ll hear his own argument for not doing what I’m telling him to do. In contrast, if I start out by really listening to him and finding out about the reasons for his ambivalence, A) I’m not fruitlessly trying to control the patient, and B) I don’t trigger the righting reflex.”

If you want to focus on things that are normally beyond your control, do so by taking action, not by worrying or stewing in anger. Dr. Piso notes that many things that are beyond a physician’s control in day-to-day practice might not be beyond your control if you decide to go the extra mile to bring those areas into your circle of influence. “Some doctors hire lobbyists in Washington and try to initiate or support legislation that will bring about reform and change things,” he points out. “That’s admirable, and there are people in ophthalmology doing that today. What I’m saying is, if you want to fight the good fight, take strategic, effective action instead of worrying and feeling stressed.

“Of course, the doctors making that extra effort are in the minority,” he notes. “The majority are simply angry, frustrated, scared or having some combination of those emotions, and they are at risk of falling into this pooled activity of ‘misery loving company,’ feeling validated and somehow justified in their resentments and criticisms, but not taking any effective action. If you’re unable or unwilling to devote time and energy and take real action to change things, the most effective option is to accept the situation and shift your focus onto areas that are currently within your ability to influence or control.”

Dr. Piso explains that his book Healthy Power frames our life choices in terms of eight areas in which we have the choice of handling things in either a positive, constructive way or an unhealthy, nonproductive way. “In Chapter Six I talk about the choice between focused action and fragmented activity,” he says. “Those are polar opposites. On the healthy power side of the ledger, using focused action in deliberate, effective ways is a tremendously good coping strategy and a source of personal power development.

“Engaging in focused action has three facets,” he continues. “The first is selection, which refers to consciously, deliberately choosing what we focus on. As already noted, this is important because whatever we focus our attention and effort on tends to expand, whether it’s positive or negative. Consciously choosing our focus is very different from allowing others to choose it for us.

“That brings us to the second facet, which is concentration,” he continues. “We all encounter very unhappy people who are marinating in their negative focus, who are trying to make themselves feel better by getting us to join them. If you’re not concentrating on your focus, an individual like that can redirect your focus down a dead-end path. Concentration means the ability to put on blinders when necessary, and be diligent about maintaining your focus without being deterred, derailed or distracted.

“The third facet is the perspective we have regarding our focus,” he says. “We get to choose the lens through which we see things (an apt metaphor for ophthalmologists). That’s really important, because our perception defines our reality; the way we perceive things determines our quality of life experience. Everyone knows the old adage about seeing a glass as half full or half empty. A person who sees the glass as half full is looking at the glass as a resource, a positive asset, something he can build on. A person who sees it as half empty is already in a scarcity mentality and ascribing something negative to it.”

Dr. West notes that one way to take action without having to “quit your day job” is to join ophthalmology associations and urge them to fight on your behalf. He points out that many large organizations that represent ophthalmologists are working on these issues, especially in the area of regulations and government oversight.

“One way to regain some control is to enlist others in greater positions of power to work on your behalf,” he says. “Become part of your local or state medical society and start attending advocacy meetings. Decisions about the use of their resources are not made in a vacuum, so you can make sure the leaders of these organizations are prioritizing the need to address the issues that impact you the most. If you believe you don’t have anyone in your corner helping you to make things better, the sense that things are out of your control will only become greater. Working with a society will let you feel more supported and give you a way to assert some influence over things that otherwise seem far beyond your control.

|

“Of course,” he adds, “you can always decide to become an advocate yourself, but most physicians have enough on their plates already.”

Above all, don’t ignore your stress—do something about it. “The literature suggests that when physicians get so out of balance that they’re experiencing distress, it harms their ability to take optimal care of their patients,” says Dr. West. “So if you know that you’re feeling stressed, don’t just accept it as something that you have to endure. Do something about it.”

Here are some practical steps you can take that may help make things less stressful:

• As much as possible, get help managing nonmedical tasks that have to be completed. “The vast majority of doctors just want to see their patients, do their procedures and practice medicine,” notes Dr. West. “Getting help with the other tasks is a simple and effective way to reduce stress. Pursue your passion and get assistance dealing with the unpleasant things that you can’t eliminate.”

• Get your practice leaders to prioritize changing some of the things you can’t change yourself. Dr. West notes that managing all of this shouldn’t be solely the job of the physician. “Group practices, organizations and institutions have to step up and take some responsibility for making things better,” he says. “If we simply say, ‘The reality is, physicians just have to deal with all of this and then find some way to mitigate their stress,’ we’re going to end up with a lot of cynical physicians. Organizations and practices have to take responsibility for their role in things.

“For example, group practices have different levels of receptiveness regarding part-time physician employment,” he continues. “Many physicians would be a lot less stressed if they could reduce or adjust their hours. Even allowing a doctor to start later so he or she can drop the kids off at school in the morning and make up the time later in the day could lower stress levels significantly.

“In reality, all of these things stand to benefit practices enormously,” he notes, “because physician satisfaction is a positive for the bottom line, even if it feels like supportive changes might undercut revenue in the short term. For one thing, when doctors are less stressed, they provide better patient care. In addition, when physicians see that they’re being protected, they repay that with loyalty and a sense of shared responsibility for the success of the practice. If a physician feels that the practice isn’t supportive and leaves to find a better situation, bringing in a new ophthalmologist can be incredibly expensive and stressful for a practice. So stepping up and helping practice members deal with things beyond their control is a smart move for the practice.”

• Talk to your colleagues about the things that stress you out. “The reality is, most physicians don’t do much to support each other,” says Dr. West. “Many doctors feel isolated. They’re dealing with challenges that are largely beyond their ability to control, and they feel like they’re alone in dealing with them. For example, I’m in a huge group practice with 2,000 physicians and scientists at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. We’re surrounded by 2,000 colleagues, and yet people tell me that they sometimes feel like they’re alone at work. I think a sense of community among physicians has eroded over the years, and it doesn’t help when people not only feel like things are beyond their control, but feel they’re the only one faced with them. The truth is very different. We are a large community, and we can do a better job of supporting each other.

“One thing we’ve learned from our work is that simply getting physicians together on a regular basis makes a difference,” he says. “It can help doctors reframe their problems, and it allows them to remind each other of all the good things they’re part of, and the things they can, in fact, control, such as their relationships with their patients. Feeling that you’re part of a supportive community of physicians is really important.”

• Consider taking a class in stress reduction. Dr. Goodman points out that mindfulness-based stress reduction classes are available in most big cities, as well as online. “The eight-week course we teach is also taught by many other individuals across the country,” he says. “It was created by John Kabat-Zinn and Saki Santorrelli at the University of Massachusetts, where they train and certify the individuals who teach the course. They call their system ‘mindfulness-based stress reduction.’ It’s widely available.

“You can also explore techniques of mindfulness on your own,” he continues. “The University of Virginia Mindfulness Center has a website (med.virginia.edu/mindfulness-center/) with lots of helpful information. The University of Massachusetts Mindfulness Center also has a website (umassmed.edu/cfm/), where they have practices, links, guided meditations and a bibliography of books you can read to find out more about using mindfulness to reduce your stress level and deal more effectively with the pressures you face.”

• Don’t lose sight of the value of your work or your original motive for becoming a doctor. Dr. West notes that it’s important to remember how much the work you do contributes to your patients’ lives. “When I treat a patient, I remind myself that I’m not just helping that patient; my work has a ripple effect,” he says. “I’m also helping the patient’s family and everyone who cares about that person, and I’m enabling that patient to be more involved in his or her community. As physicians, we lose sight of that far too often. I’m not an ophthalmologist, but people prize their vision; it’s hugely important to an individual’s quality of life. Even something as basic as cataract surgery, which I’ve been told many ophthalmologists think of as routine, makes a huge difference in people’s lives. The work you do as an ophthalmologist has an enormous impact, and it’s important to remember that.”

“It’s easy to get lost in the forest of regulations and pressures that come with being a doctor today,” adds Dr. Goodman. “I believe it’s important for doctors to reconnect with their original intention. Most of us didn’t go into medicine primarily to make money; most of us became doctors so we could help people. Focusing on that intention can help offset the stressful distractions all around us. Remember what’s really important to you.”

• Have compassion for yourself. Dr. Goodman notes that doctors can be so focused on helping others that they lose sight of their own well-being. “One of my adages, when teaching physicians and health-care providers, is, self-compassion first,” he says. “When we’re suffering, whether it’s because of practical issues or our internal dialogue escalating our frustration, we have to acknowledge that we’re suffering and prioritize spending some time and energy addressing our own needs.

“Doctors can get very busy and hung up on the idea that they have to do more than they’re already doing,” he continues. “Instead, you should make a point of taking the vacation time you have coming to you; make the effort to eat right; get some exercise; take time to write in a journal; try meditation; spend some time out in nature; set aside time to be with your family; take time to engage in activities you enjoy; and invest a little time in learning more about how to take care of yourself. Having compassion for ourselves is one of the ways we learn to calm ourselves and get back into more of a wisdom and problem-solving mode.

“The reality is,” he concludes, “if you don’t take care of yourself, you’ll have a much harder time taking care of your patients.”

Focus on the Right Things

In the end, one of the most important pieces of advice is to manage your focus. “Don’t focus on the things that are out of your control,” Dr. Piso says. “Don’t devote your psychological bandwidth to the swirling whitewater of things around you that are going to upset and distress and exhaust you. Instead, shift your focus proactively and stand on the solid rock of what you choose to do. Focus on what’s in your control, using the three facets of focus mentioned earlier: selecting your focus consciously; concentrating on that focus so that you see it through to completion; and maintaining a positive perspective that ensures you appreciate the value of your efforts and the positive potential of the situation.

“This strategy will give you a sense of control, because it’s coming from inside you,” he says. “It’s not being pushed onto you by the world around you. It will let you maintain a strategic stance that’s empowering and productive, instead of being overwhelmed by the things you can’t control.” REVIEW

1. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general U.S. working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:12:1600-1613.