|

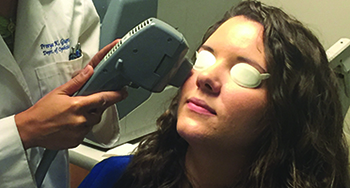

| LipiFlow combines heat from beneath the lid with mechanical squeezing. |

LipiFlow

TearScience’s LipiFlow, also known as thermal pulsation, was the first device aimed specifically at MGD-related evaporative dry eye. It combines heat with physical massage to liquefy and express the meibomian gland contents in an effort to get the lipid layer of the ocular surface back to normal again.

The device consists of a small piece that looks like a scleral contact lens that slides beneath the lids and over the globe. Some physicians administer one or two drops of topical anesthetic before fitting the device beneath the lid, for patient comfort. This lens-like piece emits heat outward, to the lids, while at the same time protecting the eye itself from the heat. The second part of the device, which is connected to the shield, sits outside the eye on the lids and provides a pulsatile squeezing of the lids to try to open the gland orifices and express the oil that’s being warmed and liquefied by the heat. The treatment takes 12 minutes.

Jack Greiner, DO, PhD, of the Schepens Eye Research Institute, has conducted a long-term study of LipiFlow, following patients for up to three years. In the study, 40 eyes of 20 patients with MGD and dry-eye symptoms underwent a LipiFlow treatment at Dr. Greiner’s office. The outcomes were measured in terms of meibomian gland secretion score (determined by grading three sets of five glands on the lower lid on each gland’s ability to secrete healthy, clear oil [a grade of 3] down to nothing [a grade of zero]) and tear-film breakup time. Patients also rated their symptoms on the Ocular Surface Disease Index and Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaires.

In the study, MGS scores increased from 4.5 at baseline to 12 at one month (p≤0.001). This improvement continued at three years (score: 18.4). TFBUT at baseline was 4.1 seconds, and improved to 7.9 seconds at one month (p≤0.05). However, the difference between TFBUT at three years wasn’t statistically significant (score: 4.5 seconds). The average OSDI score improved significantly from a 26 at baseline to 14.7 at one month (p≤0.001), but returned to baseline levels at three years (22.5; p>0.05). The SPEED scores, however, remained improved at both one month and three years: The average SPEED score improved from a 13.4 at baseline to 6.5 at a month (p≤0.001), and the improvement continued at three years (9.5; p≤0.001).1

“At the 12-month time point, the tear breakup time dropped out as being statistically significant,” says Dr. Greiner. “When you get to the two-year time point, the OSDI score dropped out as being significantly better than baseline. In terms of adverse events, after the treatment, there’s some minor irritation that’s usually gone in an hour. Sometimes the vessels on the lid margin, which are very tiny, will be more fragile on people with various skin textures and you’ll see some subcutaneous hemorrhaging along the lid margin. However, if you look at that patient in a day or two, the hemorrhage signs are gone.”

LipiFlow isn’t for every patient, however, and in one study around 20 percent of the subjects didn’t report an overall improvement in symptoms.2 Because of this, doctors say patients should fit a certain profile to ensure success with the procedure. “You can’t just put anyone in LipiFlow treatment,” says Dr. Greiner. “The patient can have a severe amount of dry eye but you need some glands that are capable of being opened. What we’re usually looking for is someone with at least six glands in his lower lid that are open to some degree before we’ll do LipiFlow. If there aren’t this many, we might do lid expression for a few weeks or months ahead of the LipiFlow treatment, as well as have him do warm compresses and lid therapy at home.” Another factor some surgeons say may be important is the occurrence of incomplete blinking. If a patient has persistent incomplete blinks, surgeons say, it’s a problem that will always be there and LipiFlow might not be successful in such a patient.

In the right patient, Dr. Greiner has been pleased with the results. “Looking at this technology, for me it was completely unexpected that it would last this long,” he says. “When we could get an eye drop to last six or eight hours, we were excited, but we never expected to see something last nine months or a year.”

ThermoFlo

ThermoFlo is another in-office treatment performed by either the doctor or a staff member that takes aim at MGD-related dry eye. Like LipiFlow, it combines pressure and heat, but in a fashion that differs slightly from LipiFlow’s approach.

|

| The ThermoFlo device heats the oil glands from outside the lid. Periodic pressure for expressing the glands’ oil is applied by the practitioner holding the device. (Image courtesy James Lewis, MD.) |

ThermoFlo hasn’t been studied as formally as LipiFlow, but anecdotal reports seem to show it’s at least as good as warm compresses, without the need for patient adherence with the compress regimen. “In virtually every patient, the treatment lasts a week,” says Elkins Park, Pa., ophthalmologist James Lewis. “By two weeks after their first treatment, about half of the patients feel that another treatment is needed. Three or four ThermoFlo treatments, two weeks apart, are usually enough to evacuate the remaining healthy glands, and patients seem to do considerably better then. We usually don’t need to do a fifth or sixth treatment.”

In his practice, Dr. Lewis studied 45 patients referred to him for dry-eye treatment. All were currently using treatments such as warm compresses, lid hygiene, Restasis, non-preserved artificial tears, temporary or permanent punctal occlusion and/or low-dose ocular steroids, but hadn’t gotten satisfactory relief from them. Two weeks after the ThermoFlo treatment, the patients completed a questionnaire, and 89 percent reported some improvement in their symptoms. “In my practice, after ThermoFlo we’ve noticed improved Schirmer’s testing results, improved osmolarity and improved TFBUT as measured by the Oculus Keratograph,” Dr. Lewis avers. “We’re having TFBUT extend as much as five seconds after a ThermoFlo treatment.”

In everyday practice, Dr. Lewis doesn’t use ThermoFlo alone, but instead makes it part of patients’ dry-eye regimen. “In clinical practice, we rarely do a treatment unassociated with other therapies, and will accompany it with topical steroids, the use of punctal occlusion and sometimes the addition of Restasis,” he explains.

Intense Pulsed Light

The treatment known as intense pulsed light is actually a repurposing of a device used in the dermatology field for skin treatments.

IPL for treatment of dry eye was initiated by Memphis surgeon Rolando Toyos. Dr. Toyos received a research grant from the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery to study IPL for evaporative dry eye, and eventually developed a laser for the treatment with the device company Dermamed. His approach using this device for ocular indications is now being taught to various ophthalmology clinics and practices via lectures and training courses.

In July 2015, Duke Eye Center surgeon Gargi Vora co-authored a retrospective study of IPL to get a sense of its efficacy. “For an ocular IPL treatment, we first apply ultrasound jelly to the area under the lower lid/lateral canthal area and the upper cheek,” she says. “IPL is only used to treat the lower lid/lateral canthal area, not the upper lid, because light directed at the upper lid could penetrate it and damage the eye itself. We also put special eye shields on the ocular surface itself, and have the patient close his eye over them, to make sure no light energy enters the eye. Alternatively, some practitioners place shields over the lids. For the treatment, the patient receives 10 to 15 treatment spots on the upper cheek and lateral canthal area, and the physician makes two passes. To the patient, it’s similar to facial skin treatments, with little zaps to the skin. Patients can feel some warmth during the procedure and the zaps can be a little uncomfortable, so we use the jelly to help soothe the skin. After the second pass, the shield and jelly are removed, and the patient receives warm compresses over his lid to soothe it as well as help the oils in the glands melt a little.

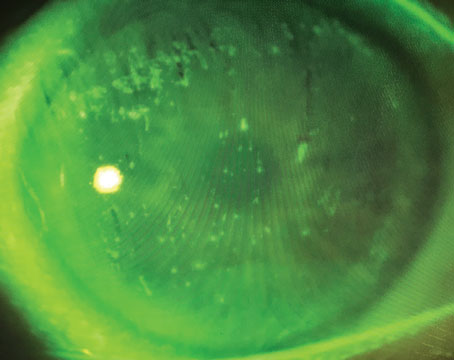

|

| Intense Pulsed Light manages to get an effect in the meibomian glands of the lower lid, and sometimes the upper lid, by treating blood vessels in the lower lid/lateral canthal area. (Image courtesy Gargi Vora, MD.) |

In the Duke study, Dr. Vora and her colleague Priya Gupta, MD, administered at least three IPL treatments to evaporative dry-eye patients. Drs. Vora and Gupta report a significant decrease in the level of lid margin edema, facial telangiectasia and lid margin vascularity, as well as an improvement in meibum quality score (p<0.001 for all measurements). There was also a significant increase in oil flow score and TFBUT (p<0.001). Subjective symptoms improved, with a statistically significant decrease in OSDI scoring (p<0.001). The patients had relief for several months, and maintenance treatments were necessary every six to 12 months.3

Dr. Vora says the improvements grew over time. “In our study, there was a range of three to six treatments per patient, with an average of four,” she explains. “Each treatment was separated by three to six weeks, the scheduling of which wasn’t really symptom-based but more about when the patient could come in. We noticed that patients saw improvement by the second treatment, which was also the date of the second follow-up—after the visit on the day of the procedure—which was about three weeks after the initial IPL treatment.”

Ophthalmologists are still curious about the exact mechanism of action involved with IPL. “In dermatology, IPL is used for rosacea and to reduce telangiectasia,” Dr. Vora says. “Then, in 2002, Dr. Toyos found that dermatology patients also had improvement in meibomian gland dysfunction and dry-eye disease. We’re not 100-percent sure of how IPL works in dry eye. The way it works in rosacea cases, at least as believed by dermatologists, is that oxyhemoglobin in the blood vessels absorbs the light energy and then converts it to heat, which causes a coagulation or closing of the vessels. Patients with meibomian gland dysfunction often have abnormal vessels at the lid margin or ocular rosacea, so we’re assuming that the oxyhemoglobin is absorbing the energy from the IPL and closing off the vessels, preventing inflammatory mediators from reaching the meibomian glands and allowing them to become inflamed.

“Another theory of how it works is that, due to a kind of local heating effect, it’s similar to LipiFlow in that it’s causing a melting of the oils in the glands to let them be secreted more smoothly,” Dr. Vora continues. “We think that the heating effect might also decrease the bacteria in the lid margin, decreasing the inflammatory burden on the meibomian glands. The Demodex parasite on the lid margin is partially treated, as well. Ultimately, we don’t know exactly what IPL does, but I imagine it’s a mix of these three things that results in improvement.”

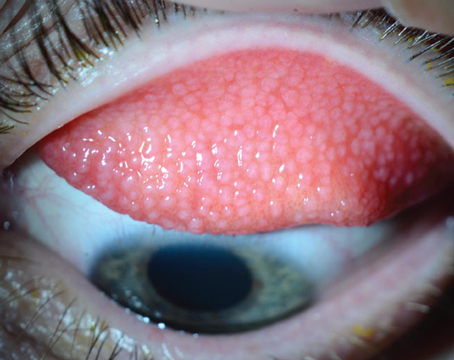

Blephex

Blephex (RySurg; Palm Beach, Fla.) is a new in-office tool for use on patients with blepharitis, and, as such, it appears to also ease the signs and symptoms of evaporative dry eye associated with blepharitis.

The Blephex is a handheld tool similar in appearance to an electric screwdriver. The doctor or technician affixes a small disposable pad to the rotating end of the Blephex, and puts a small amount of lid cleaning soap on the pad. As the cleaning pad rotates at high speed, it’s used to scrub away debris from the lid margins under topical anesthesia. From the dry-eye perspective, debriding the margins can open up the meibomian gland orifices, allowing the oil to return to the ocular surface.

|

| Blephex removes scales and debris from the lid margin using a rotating head, which opens up meibomian gland orifices. (Image courtesy Charles Connor, OD, PhD.) |

Dr. Connor and his colleagues say Blephex appears to be an alternative for patients who are non-compliant with lid scrubs and warm compresses at home. “If the meibomian gland is still viable when you debride the thickened tissue on top of it, it will secrete and the patient will have a positive response,” Dr. Connor says. “The cleaner used on the Blephex pad is basically the type of cleaner we’ve been using for years to clean lids; it’s a soap designed to not induce a lot of irritation in the eye. In addition to cleaning off the thickened tissue on the lid margins, the soap will kill bacteria there too. Blephex lasts about three to six months before requiring a retreatment.

“The Blephex treatment isn’t an unpleasant experience for the patient, provided you use a little stronger anesthetic,” Dr. Connor continues. “If you use proparacaine, it’s a little too weak and patients feel the vibration more. But with tetracaine patients have less sensation, so when you run the Blephex across the lid margins the patient gets less irritation. We haven’t had any patients say the treatment is painful, with the worst complaint being that it’s mildly uncomfortable or that it tickled. My gut feeling is that the old traditional treatments also work, but patients don’t really want to do them because it’s one more thing they have to add to their daily routines. They either forget, or get lackadaisical about doing them. I don’t know if Blephex works better than therapies we’ve done traditionally, but what’s nice about it is I know that it’s been done. I or my staff can do it, get a result, and not have to worry about the patient going home and doing anything.” REVIEW

Dr. Greiner has performed studies funded by TearScience. Dr. Lewis is a stockholder in Mibo. Drs. Vora and Connor have no financial interest in any product mentioned in the article.

1. Greiner JV. Long-term (3 year) effects of a single thermal pulsation system treatment on meibomian gland function and dry-eye symptoms. Eye Contact Lens 2015 Jul 28. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Lane S, DuBiner H, Epstein R, et al. A new system, the lipiflow, for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea 2012;31:4:396-404.

3. Vora GK, Gupta PK. Intense pulsed light therapy for the treatment of evaporative dry-eye disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2015;26:4:314-8.