While diagnosing some ocular conditions can be relatively straightforward, others, such as dry eye, are multifactorial and could be caused by one of many possible etiologies. You may need to perform multiple tests on a patient with suspected dry-eye-related signs or symptoms to determine the culprit and create an effective management plan. The last thing you want to do is misdiagnose the case—or fail to thoroughly screen patients—and cause them to suffer longer than necessary.

What is your personal strategy to ensure that you properly diagnose a patient with dry eye? Which tests do you perform and when? Here, cornea specialists offer guidance to help you maximize your chances of making a proper diagnosis and identify patients in need of treatment.

The Patient Interview

It’s no secret that a solid history is one of the most important tools for any doctor to help determine where to begin and which tests to perform on a patient. Obtaining inadequate current and historical patient data or failing to ask the right questions about topics such as lifestyle, medications or symptoms can cause you to overlook information that could be critical to determining the proper testing and diagnosis of the patient’s dry eye.

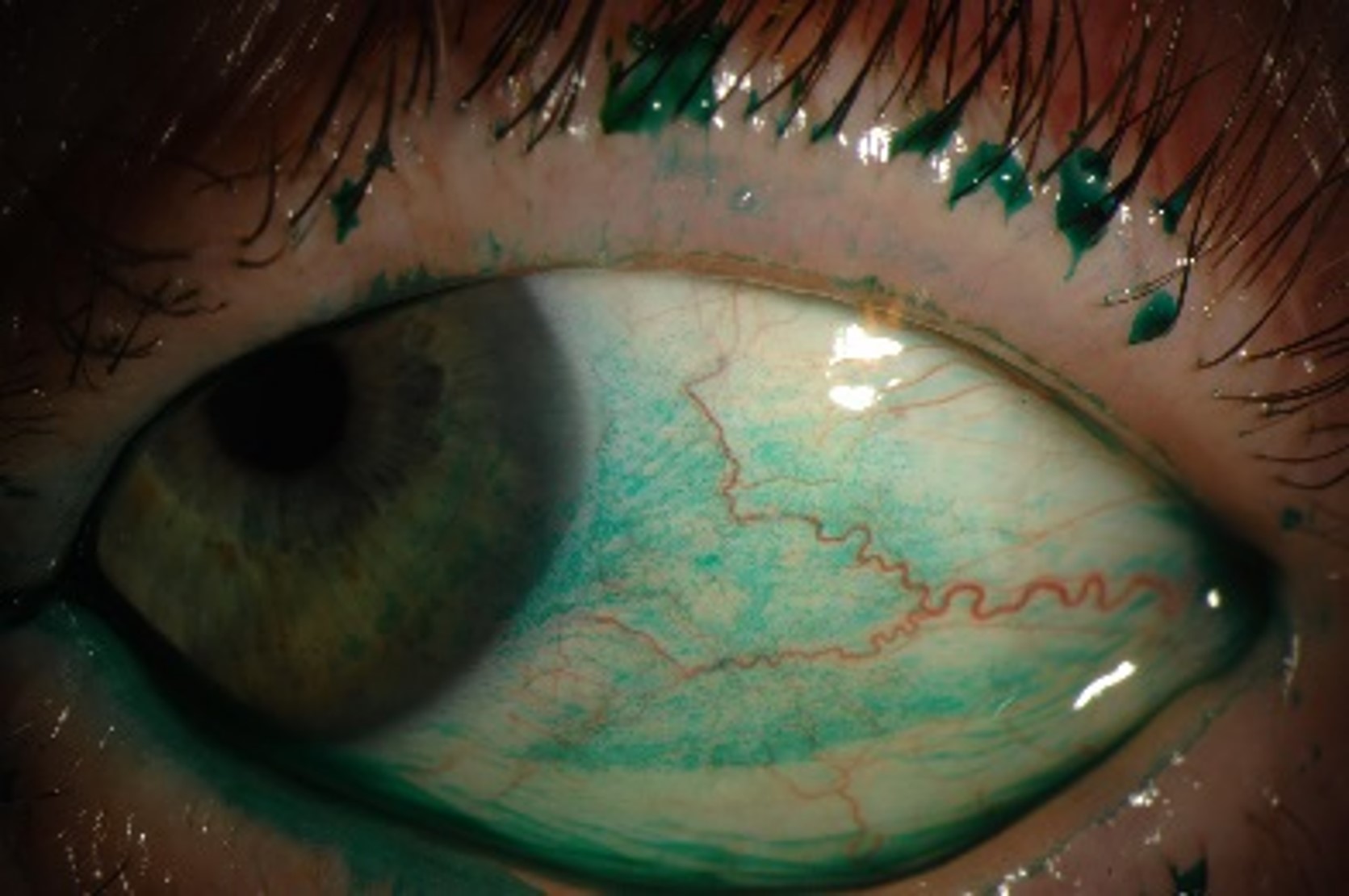

|

| Slit-lamp appearance of an eye with 3+ lissamine green staining of the bulbar conjunctiva. Photo: Esen Akpek, MD. |

“Dry eye is underappreciated and underdiagnosed, and that leads to undertreatment,” says Esen Akpek, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and director of the Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic at the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore. “We routinely check intraocular pressure and perform dilated exams to check the cornea, but most clinicians don’t check for dry eye unless a patient complains about it.”

Dr. Akpek advises, even if you don’t test the ocular surface or tear film of every patient, “at the very least, we need to be asking all of our patients how their eyes feel and how their vision is when we take their history.”

Here are several topics to discuss with patients that can help you determine what to focus on during the exam and steer toward a potential diagnosis:

Ask about symptoms. Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, chief of the cornea service at Wills Eye Hospital and professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, agrees that getting a good history and understanding the patient’s symptoms are key.

“I try to figure out what’s going on by asking the patient questions like, ‘Do your eyes feel gritty/sandy? Do they feel painful? Are they red? Do your eyes feel worse in the morning vs. afternoon or evening?’” he says. He notes that when dealing with patients who have clinical dry eye, “they tend to come in presenting with the classic feeling of grittiness or sandiness that tends to worsen as the day goes on.”

Another question to ask dry-eye suspects is whether they have difficulty with near work or if such tasks exacerbate their symptoms. “Dry-eye patients tend to be worse with what I call concentrated visual tasks,” Dr. Rapuano explains. “These include activities such as using or playing games on the computer, tablet or cell phone, watching TV or movies, reading or driving.”

Most dry-eye patients will have some version of these common symptoms (i.e., grittiness and eye strain/discomfort during near work). However, the presence or timing of specific symptoms may point you toward the possible type or severity of the condition.

“If the patient has any level of blepharitis, the eyelids tend to be red from the inflammation, and while they may have symptoms of dryness and grittiness, it tends to be worse in the mornings,” says Dr. Rapuano. He adds that, prior to the exam, this is the first hint of whether you’re dealing with a case of blepharitis or aqueous-deficiency. Keep in mind that lagophthalmos is another potential diagnosis for patients who experience the most ocular discomfort in the mornings.

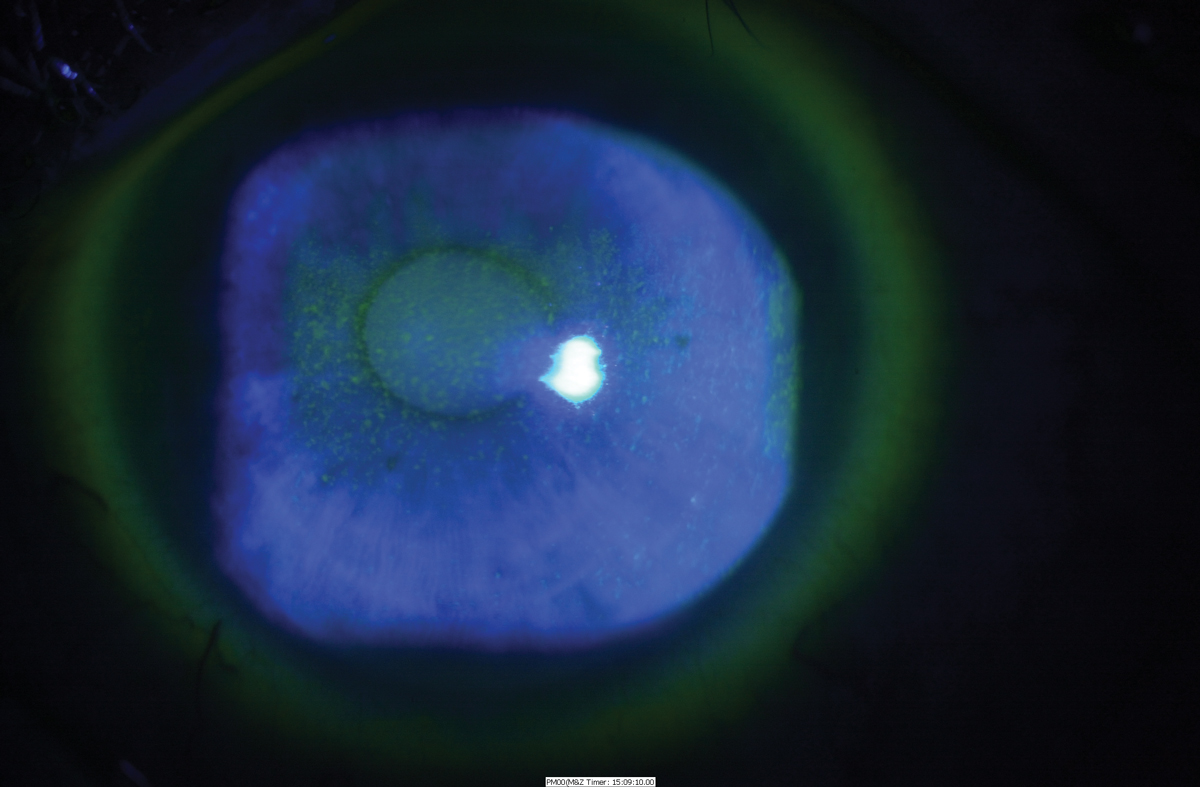

|

| Slit-lamp appearance of a cornea with 3+ central macro epithelial erosions, under cobalt blue light. Photo: Esen Akpek, MD. |

Another important question to ask patients who complain of dry eye is what helps their symptoms improve. “Ask if artificial tears help alleviate the discomfort. If they say no, or if the drops only help for a short period of time, the patient may have blepharitis or allergies,” says Dr. Rapuano.

Dry eye questionnaires, such as the Ocular Surface Disease Index, SPEED questionnaire or the University of North Carolina Dry Eye Management Scale, can be efficient tools to help you gather some of this information about the patient and their symptoms before they sit down in your chair, freeing up more time for the physical exam.

Ask about allergies and medications. Allergies are potential culprits of dry-eye symptoms that’ll be easier to identify through a detailed case history. “Sometimes, the ocular symptoms are related to the allergy itself, and other times, they’re related to the medication the patient is taking for the allergy,” Dr. Rapuano points out. To rule out this potential cause, ask the patient about any allergies they know or suspect that they have, as well as which, if any, medications they currently take or were previously on.

Besides allergy medication, there are numerous other types of drugs known to cause dry eye. “Antihistamines are probably the highest on the list when it comes to medications that cause eye dryness and related symptoms,” says Dr. Rapuano. One study published earlier this year investigated various medications that seem to cause or worsen dry-eye disease, including “systemic medications such as antihistamines, antihypertensives, anxiolytics/benzodiazepines, diuretics, systemic hormones, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic or inhaled corticosteroids, anticholinergic medications, isotretinoin (causes meibomian gland atrophy) and antidepressants.”1

Dr. Akpek adds that she also occasionally sees dry eye in patients on high doses of painkillers, especially those with an underlying diagnosis of something like fibromyalgia or arthritis. “These are the patients that already have aqueous tear deficiency and a decreased blinking rate, so I try to limit their medical treatment if I can, without having an impact on other areas of their health.”

Many patients fail to accurately report past and current medication or drug use in their paperwork, one reason being they may think it’s irrelevant or are afraid they might be told to discontinue using their medication. “If you do suspect that a patient’s medication may be causing or contributing to their symptoms, reassure them that this doesn’t mean they need to stop the medication, but we may have to compensate by using a prescription drop like Restasis or Xiidra,” notes Dr. Rapuano.

Ask about contact lens wear. “Contact lens wear can certainly cause dry eye; it’s associated with increased risk of blepharitis,” Dr. Rapuano points out. “Some people say their eyes feel better when they put contact lenses in, and others say it makes them feel worse.” For patients who do seem to have ocular discomfort relating to their contact lenses, he notes that switching them from reusable to daily disposable lenses will help avoid protein buildup and eliminate the need for disinfecting solution that could be irritating the eye. Decreasing the time of wear—for example, from 16 hours a day to eight hours—could also be a viable suggestion for patients whose symptoms seem to worsen throughout a day of lens wear.

Similar to how patients may be hesitant to answer truthfully when asked about medications, the same goes for questions regarding their contact lenses; some may fear they’ll be instructed to stop wearing them. Dr. Rapuano notes that most of the time, switching the lens type or material or changing wear habits can help alleviate the issue. However, he does recommend discontinuing wear in more severe cases of dry eye if you suspect contact lenses are the cause.

Ask about surgical history. “Often when you ask patients if they’ve had ocular surgery, they’ll say no,” says Dr. Rapuano. “Then, you ask them if they’ve had LASIK, and they’ll say ‘oh yeah, I got that a few years ago; I forgot to mention it.’ The other surgery to specifically ask your patients about is eyelid surgery. They often won’t remember that they had their lids lifted, or they just don’t want to admit it.” Even if the patient’s paperwork reflects that they have no surgical history, be sure to ask again in the exam room.

The Examination

Once you have a thorough case history and symptom report, the next step toward a diagnosis is the physical examination.

According to Dr. Akpek, examining patients for signs of dry eye shouldn’t only be for individuals who report experiencing symptoms. “Some patients may never report symptoms to their doctor because they assume that it’s normal or due to allergies or aging, which is a major reason why underdiagnosis is so common,” she says. For this reason, she suggests that “observing the ocular surface and tear film should be part of a comprehensive eye examination.”

For Dr. Akpek, after taking the patient’s history, she performs the following minimum battery of tests: tear osmolarity (done by the technician), unanesthetized Schirmer’s test, tear-film breakup time and pattern with fluorescein, corneal fluorescein staining (checking the score after two or two and a half minutes) and conjunctival lissamine green staining—both according to the ocular staining score—and, lastly, meibomian gland examination and meibum score.

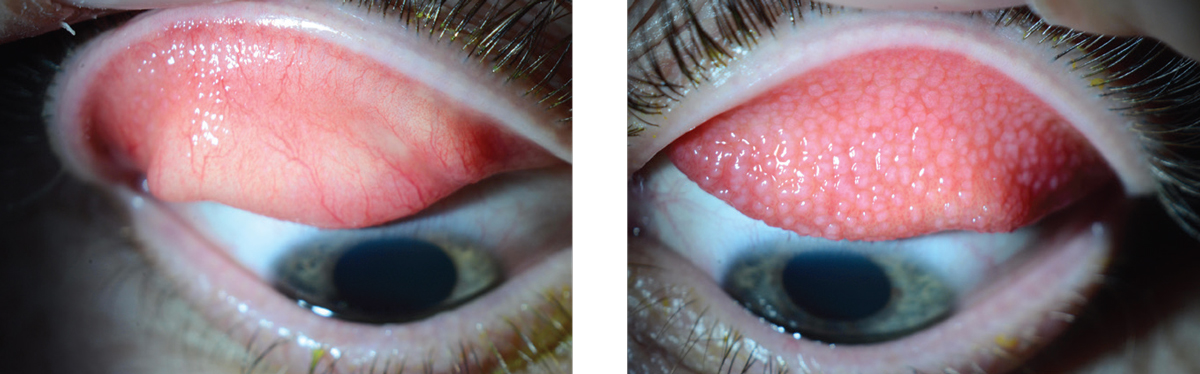

Dr. Rapuano says that when he first performs an exam on a patient to evaluate signs of dry eye, “I first look at the eyelids for signs of anterior blepharitis, posterior blepharitis or Demodex. I find it critically important to flip the lids. Have the patient look up and look under the lower lid. You might see allergy bumps even in patients who you didn’t suspect had an allergy,” he points out.

What’s even more important is flipping the upper lid, Dr. Rapuano suggests. “For a lot of patients who have nonspecific dry-eye symptoms, when you flip the upper lid, you might find something you weren’t expecting,” he says. “For example, you may find that they have floppy eyelid syndrome, where the eyelids are super lax, but they just kind of divert overnight, and the patient will often have worse symptoms in the morning.” He adds that looking under the upper lid could also reveal allergy bumps, signs of giant papillary conjunctivitis from contact lens wear or less common conditions such as vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Flipping both of the lids can also reveal signs of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, says Dr. Akpek.

|

| This patient’s left upper lid (right photo) shows moderate to severe allergic conjunctivitis related to contact lens wear seen by the clearly visible allergy bumps. Under the right eyelid of the same patient (left photo), a mild case of allergic conjunctivitis can be observed. Photo: Christopher J. Rapuano, MD. |

Rarer diseases can also be detected via observing the eyelids. “When you have the patient look down and lift the lids, you can look at the superior conjunctiva, and you may find superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis,” says Dr. Rapuano. “Or, when you have the patient look up and examine the inferior lid, you may be surprised to find that there’s scarring and possibly foreshortening of the inferior conjunctival fornix, which can be indicative of an early pemphigoid situation.”

Pemphigoid is a rare autoimmune condition that can affect patients at any age but tends to be most prevalent in those older than 60.2 Signs of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, affecting 60 to 70 percent of people with mucous membrane pemphigoid, include bilateral conjunctival cicatrization or scarring. “It’s a very serious, progressive disease that starts with mild signs and symptoms,” says Dr. Rapuano. “If you catch it early, it’s much easier to treat before it causes a large amount of scarring and potentially results in loss of vision.”

Decoding the Staining Pattern

Evaluating the tear film using trusty fluorescein dye can help you determine if the dry-eye symptoms are due to an aqueous deficiency or another cause. “If I look at the tear film and it’s basically non-existent or there’s no good tear lake, then it’s more likely a case of aqueous-deficient dry eye,” notes Dr. Rapuano. “If there’s significant punctate staining on the cornea, that indicates ocular surface disease. The staining pattern may help you determine whether it’s more superficial punctate keratitis, which is often superior. If it’s a poor blink, it’ll be kind of central or inferior SPK. If the staining is more diffuse, it could be dry-eye disease or SPK.”

Next, Dr. Rapuano uses lissamine green to highlight any conjunctival problems. “There are some patients where you’ll put fluorescein in the cornea, and everything looks pretty normal,” he says. “But then, you put the lissamine green stain in, and the conjunctiva lights up with significant damage. That tells you that there’s some serious ocular surface disease going on, which you may not have noticed by staining only with fluorescein.” Dr. Akpek adds that “conjunctival staining is an indicator of inflammatory dry eye and is commonly seen in Sjögren’s and other autoimmune conditions, such as rheumatoid scleroderma or graft versus host disease.”

Dr. Akpek, who also recommends staining with both fluorescein and lissamine green, uses a yellow filter to more clearly observe the corneal staining pattern. She notes that while corneal staining may not ascertain the cause of the dry eye, “the impact of staining is high when it comes to symptoms of discomfort, pain or vision-related quality of life.” She continues, “If the central staining score is high, I suspect a patient has vision difficulty, while staining anywhere on the cornea can indicate pain. Central staining could be suggestive of an aqueous deficiency, but if a patient has decreased blinking rates, such as from Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, they may also have central staining.”

In summary, Dr. Akpek notes that “the staining pattern depends on what you find in the rest of the exam. You need to perform a good, comprehensive exam to understand what the pattern means.”

Meibomian Gland Dysfunction

As a leading cause of dry-eye disease, this differential is one that must always be considered when patients complain of ocular dryness or discomfort. Physically examining the eyelids and meibomian glands may suggest whether the dry eye may be a result of MGD. However, the best way to confirm or deny the presence of this condition is by squeezing the lids to see what kind of secretions are produced by the meibomian glands.

“If I can’t get any secretions, that’s bad, and that tells me that there’s significant MGD,” says Dr. Rapuano. “If I get thickened, sort of unhealthy secretions, I know that the glands are functioning, but they’re not functioning very well. If I get great secretions, then I assume it’s less likely that the dry eye is an MGD-related issue.”

Neurotrophic Keratitis

“One condition that we’ve been focusing more on in the past several years is neurotrophic keratitis,” Dr. Rapuano says. “You have to ask yourself, ‘is the patient neurotrophic? Is there a component of neurotrophic keratitis that’s possibly giving them the ocular surface disease?’” He notes that if staining reveals a fairly diffuse SPK but the patient isn’t as symptomatic as you would expect, consider this differential. Various ocular and systemic conditions are commonly seen in patients who develop neurotrophic keratitis including diabetes, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, chronic dry eye, multiple surgeries and neurological problems such as stroke.

The easiest way to test corneal sensation is by touching the patient’s eye with the cotton end of a Q-tip and asking if or how much they can feel it. If you plan to test the patient’s corneal sensation, be sure to communicate to the technician that it’ll need to be completed before the patient receives numbing drops.

Objective Dry-Eye Tests

Physicians also add one or more objective tests to help pin down a diagnosis and/or the severity of the patient’s condition.

• Osmolarity testing. This test is sometimes used to help determine which patients may have clinical dry eye. A recent study evaluated the performance of two osmometers on the market—Trukera Medical (formerly TearLab) and I-Pen—and found that both instruments have good accuracy and repeatability in vitro, though repeatability did decline past mid-range osmolarities.3

Just last month, Trukera Medical announced its new ScoutPro osmolarity system, which is the first portable osmometer in the United States. Using any of these devices may be helpful to confirm whether a certain dry-eye treatment is working by allowing you to objectively measure a change in tear osmolarity.

In a poster presentation from the 2009 American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting, Foulks et al found that the cut-off value for moderate to severe dry-eye disease for the Trukera osmolarity system is 316 mOsm/L, while a value between 308 mOsm/L and 316 mOsm/L indicates mild dry eye. According to research on the I-Pen osmolarity system, a cutoff value of 318 mOsm/L was recommended to diagnose clinical dry eye.4

• LipiView. This interferometer from J&J Vision/TearScience captures both photos and videos of the meibomian glands that allow you to measure the thickness of the lipid layer in tears, assess blink dynamics and observe meibomian gland structure, all of which can be useful metrics to help evaluate and diagnose dry-eye disease. Clinical research characterizes a lipid layer of less than 60 nm as thin, between 60 nm and 100 nm as normal and 100 nm or above as thick. One study reported that three of four patients who report severe dry-eye symptoms have thin lipid layers of 60 nm or less, while roughly three of four patients without symptoms have relatively thick lipid layers of 75 nm or greater.5 However, other research has also shown that those on the other end of the spectrum with thick lipid layers may be suffering from dry-eye disease, too. Data from one study revealed that ocular surface staining and tear-film breakup time were significantly worse in those with thick lipid layers than in those with thicknesses in the normal range.6

• Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) tear testing. This diagnostic tool helps identify patients with ocular surface inflammation. One study found that the results of the MMP-9 test correlated well with subjective symptoms evaluated by the OSDI (p=0.001), tear-film breakup time less than five seconds (p<0.013), Schirmer’s test (p<0.001), conjunctival staining (p<0.001) and corneal staining (p=0.007).7

“If I’ve been treating a patient with a small amount of inflammation and I’m considering starting them on steroids, I might use the MMP-9 test to confirm whether there really is inflammation going on,” says Dr. Rapuano. As with the tear osmolarity test, the MMP-9 can also be useful in evaluating treatment response.

• Schirmer’s test. Among the oldest objective tests for measuring dry eye, the Schirmer’s test is still used today by many clinicians to assess tear production. “Especially for new patients referred for dry eye, I’ll conduct a Schirmer’s test, but I’ll do it with anesthesia so I can find out what the basal tear secretion is, not the reflex tearing,” says Dr. Rapuano. “If the score is greater than 10, or certainly greater than 15, aqueous deficiency is lower on my list of potential causes. If the score is five or below, aqueous deficiency is much higher on my list. If they score in the gray area between five and 10, the Schirmer’s test may not be super helpful,” he explains. “This is not the greatest test in the world, and it has a lot of variability, but it can help confirm patients with very low or normal tear production.”

Dr. Akpek, on the other hand, chooses not to use anesthesia when conducting the Schirmer’s test. “Unanesthetized Schirmer’s, but not anesthetized Schirmer’s, is included as a criterion in the classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome,” she explains. “In evaluating a patient with any ocular surface disease, I want to make sure there are no underlying systemic diseases (i.e., Sjögren’s, sarcoidosis, scleroderma or graft versus host disease) because those patients are managed, examined and treated in a different way.” Dr. Akpek adds that the most common underlying conditions for any ocular surface disease are thyroid eye disease and Sjögren’s. “If the Schirmer’s score is five or less, I definitely consider the possibility of Sjögren’s in that patient,” she notes.

Takeaways

There are numerous possibilities of what could be causing your patient’s dry eye, but there are also dozens of tests and tools that can help you reach the right diagnosis. “Despite dry-eye testing being available, it’s not taken advantage of by providers,” says Dr. Akpek. “Any patient coming in for an exam should be evaluated for signs or symptoms of dry eye, and if they have either, review the history, perform a battery of tests and then go from there."

Dr. Rapuano is a consultant for Avellino, Bio-Tissue, Cellularity, Dompé, Glaukos, Kala, Oyster Point, Sun Ophthalmics, Tarsus and TearLab. Dr. Akpek is a consultant for Novalique and an investigator for Ocular Therapeutix.

1. Golden MI, Meyer JJ, Patel BC. Dry eye syndrome. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 27, 2022.

2. Schonberg S, Stokkermans TJ. Ocular pemphigoid. StatPearls Publishing. Updated March 16, 2022.

3. Tavakoli, A, Markoulli, M, Flanagan, J, Papas, E. The validity of point of care tear film osmometers in the diagnosis of dry eye. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2021;42: 140-148.

4. Park J, Choi Y, Han G, et al. Evaluation of tear osmolarity measured by I-Pen osmolarity system in patients with dry eye. Sci Rep. 2021:11:7726.

5. Blackie CA, Solomon JD, Scaffidi RC, Greiner JV, Lemp MA, Korb DR. The relationship between dry eye symptoms and lipid layer thickness. Cornea. 2009;28:789-794.

6. Lee Y, Hyon JY, Jeon HS. Characteristics of dry eye patients with thick tear film lipid layers evaluated by a LipiView II interferometer. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259;1235-1241.

7. Messmer EM, Lindenfels VV, Garbe A, Kampik A. Matrix-metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9)- Testing in dry eye syndrome. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55(13):2001.