Because glaucoma is a chronic condition affecting primarily the elderly, many of these patients develop visually significant cataracts under our care. When those cataracts are removed, medical management in the perioperative period can often be challenging, because intraocular pressure spikes and other associated comorbidities can threaten surgical outcomes. This raises an important question: Will the medications the patient is taking to treat the glaucoma affect the course of the surgery?

Depending on a variety of factors, including physician preference, contraindications, target IOP goals, etc., glaucoma can be treated with a myriad of possible therapeutic combinations. In particular, the prostaglandin analog class of medications, introduced in the mid 1990s with the advent of latanoprost (Xalatan), followed more recently by bimatoprost (Lumigan) and travoprost (Travatan and Travatan Z), have become ubiquitous in the management of glaucoma patients.1 Their popularity is understandable given their relatively low side-effect profiles, convenient dosing regimens, and perhaps most important, their potent hypotensive effects, demonstrated by many studies to be a peak reduction between 31 and 33 percent.2

However, based upon the proposed mechanisms of action of these medications, questions have arisen regarding their safety profiles in the surgical patient. The primary questions are: Should prostaglandin use be stopped before cataract surgery? If pressure lowering is needed after surgery, should prostaglandins be restarted to accomplish that goal? And if so, when is it safe to do so?

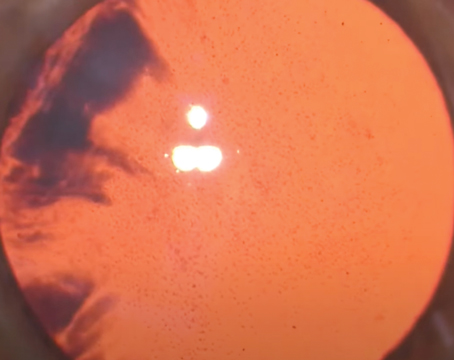

A number of case studies (and some larger series) have reported the appearance of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery, specifically noting a temporal association between the initiation of prostaglandin analog therapy and the observed side effects.

|

CME, although often reversible, is a relatively feared complication. Many cataract patients enjoy immediate post-surgery improvements in visual acuity, and subjective declines in the postoperative period caused by a complication such as CME can be discouraging for patients and doctors alike.

Why Would Prostaglandins Cause CME?

Since the mechanism of action of prostaglandin analogs is thought to be mediated at the level of the prostaglandin F2-receptor for latanoprost and travoprost (isopropyl esters), many have hypothesized that resultant alterations in the inflammatory cascade may lead to a higher incidence of CME in postoperative cataract patients.7 Lumigan, an ethyl amide with a slightly different mechanism of action, has also been implicated with CME, however.8,10 At the current time, it is still not entirely evident what characteristic of the prostaglandin analogs would cause CME.

Another explanation that has been offered, by Kensaku Miyake, MD, in his Binkhorst Medal lecture on pseudophakic preservation maculopathy at the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons meeting in 2002, is that the preservative in the medications, benzalkonium chloride, rather than the medications themselves, may be causing the problem.9 However, this connection may not entirely explain the phenomenon, as case reports exist in which Travatan Z, preserved with sofZia (a non-BAK preservative), was associated with CME as well.11 It may be that prostaglandin analogs can trigger CME via multiple mechanisms, with the presence of preservatives being only one of them. In any case, the impact of eliminating BAK is not as clear-cut as one might hope.

There is a certain irony here, in that generally speaking, prostaglandins are a very safe class of medications. That safety profile has been one of the driving factors in their mass popularity. In practice, there are only a few situations in which doctors will routinely choose from other classes of glaucoma medications, such as in the case of uveitis, pregnancy or when inflammation is present in the postoperative period.12 Despite their relative safety, understanding the limitations of these medications is imperative in minimizing the risk of a variety of complications.

In the routine medical management of glaucoma, a variety of so-called "switch studies" have demonstrated variable relative efficacies within the prostaglandin analog class of medications. In the case of postoperative CME, however, there is little evidence to demonstrate that one particular medication has a better safety profile than another. For example, bimatoprost has been demonstrated in some studies to cause increased levels of conjunctival hyperemia and local side effects; but it has not been demonstrated to increase the rate of CME relative to other medications within the class.7 This lack of clear evidence is the reason there hasn't been a big push to switch from one prostaglandin to another before or after cataract surgery.

Notably, there has been a recent trend among some practices to utilize older classes of medications such as beta-blockers as first-line agents, primarily motivated by the impact of financial constraints on patient compliance. It's important to note here that Dr. Miyake's research found similar results when comparing preserved timolol to preserved latanoprost. In clinical practice, however, beta-blockers are often used, and even preferred, for pre- and postoperative IOP management. The variability between the literature and clinical practice surely demonstrates that there is currently no clear consensus about what is the most appropriate management of these patients.

Part of the reason may be the unique nature of each glaucoma patient, as each case has a different set of risks and benefits to consider. This can be illustrated in the example of a monocular patient with end-stage glaucoma where mild to moderate postoperative IOP spikes could have potentially disastrous results. In this example, the relatively small risk of CME or prolonged inflammation may be far outweighed by the risk of deferring or inadequately treating IOP. Alternately, early-stage glaucoma patients may allow for more leniency in how aggressively IOP spikes are managed. The art of glaucoma treatment in these patients often lies in trying to determine which patients will really benefit from the inherent risks of a given intervention.

Developing a Protocol

My interest in this particular issue developed, in part, because it's encountered on such a frequent basis. Glaucoma specialists, in particular, often develop close, long-term relationships with their patients, given the high frequency with which many of them are followed.

Researching this topic objectively, however, is difficult given the enormity of data in the literature, compounded by a plethora of industry-sponsored studies that often demonstrate contradictory results. The case-reports, while many, are not a replacement for well-controlled, randomized trials. However, these trials are unlikely to occur, given the relatively low frequency of complications and a variety of ethical ramifications.

What often occurs when we find a lack of strong evidence-based recommendations is that physicians practice based on anecdotal evidence or their own personal experiences. (While this may be viewed as sub-optimal, it's important to acknowledge that this sort of decision making is part of what makes the art of medicine an art.) Fortunately, most glaucoma patients undergoing cataract surgery don't need to have an extremely low pressure in the perioperative period.

Our protocol is as follows: We generally advocate stopping prostaglandin analogs seven to 10 days prior to surgery to allow for some washout. We do not routinely stop other classes of medications, with the exception of pilocarpine, secondary to miosis.

Postoperative pressure spikes within the first day or so may be secondary to retained viscoelastics, and depending on the individual patient, may be treated medically by paracentesis or observation. We generally use beta-blockers, topical/PO carbonic-anhydrase inhibitors and/or alpha-agonists when treating medically. Use of combined agents is often especially helpful during this immediate postoperative time period, as compliance when using multiple medication regimens including steroids, NSAIDs, antibiotics, etc., often proves to be challenging for patients.

Choice of a particular agent from this list is primarily dictated by systemic/local contraindications and allergy profiles. In our experience, we feel that medications other than the prostaglandin analogs offer a more immediate and appropriate effect, due in part to their mechanisms of action (i.e., aqueous suppression versus long-term structural alterations in uveoscleral outflow pathways).

When (and Whether) to Restart

It has been demonstrated in numerous accounts, and anecdotally within our practice, that there is often a sustained IOP decrease after cataract extraction alone.13 Indeed, modern phacoemulsification surgery often provides us with a rare opportunity to stop glaucoma medications and reassess diurnal IOP curves in the postoperative period and beyond.

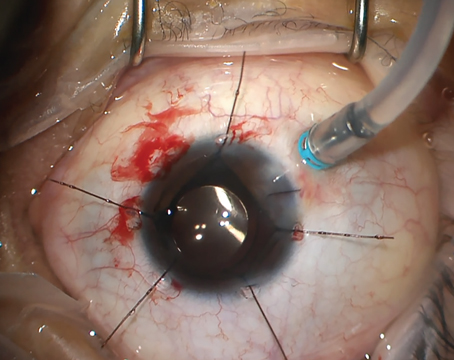

In patients with severe, uncontrolled glaucoma, cataract surgery is often coupled with guarded filtering surgery or drainage implants. More recently, some surgeons have advocated combining newer techniques such as miniature glaucoma stents, endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation or treatment with a device such as the Trabectome. However, there is a large population of patients with more moderate glaucoma, often controlled with prostaglandin analog monotherapy, who find that their IOP normalizes after cataract surgery alone, and whose IOP therapy can be safely discontinued. The decision to not restart medications is, of course, at the discretion of the provider; it's generally based upon a complicated algorithm outlining an individual's risk of glaucomatous progression.

In patients whose intraocular pressure increases to preoperative or even higher levels after surgery, as mentioned previously, we manage the IOP with non-prostaglandin analogs for a period of approximately four to six weeks. After this point, we feel that it's relatively safe to restart a prostaglandin analog, and generally can taper the other IOP medications appropriately. We advocate the use of non-steroidals for most cataract patients—but we feel they are especially needed in patients who are restarting prostaglandin analogs during the initial postoperative course. Our time frame is admittedly arbitrary, but does marginally account for the peak time frame within which CME occurs, which is often quoted as approximately six weeks.14

Most Roads Lead to Rome

The incidence of CME is still relatively low. This is especially true when defining CME as "clinical CME," which refers to a subjective decrease in visual acuity along with characteristic macular findings; this only occurs in 1 to 5 percent of cases.15 Permanent, irreversible damage is the exception, although periocular steroids and other more invasive management may be necessitated with recalcitrant CME. These techniques are not without morbidity, especially in higher-risk patients (see above), so avoidance of CME should be the ultimate goal.

Alternately, for the end-stage glaucoma patient who absolutely needs a low IOP perioperatively, including in cases of combined cataract and glaucoma surgery, prostaglandin analogs can be a potent weapon in the armamentarium when used appropriately. As with all interventions, a thorough and educated analysis of the risks and benefits will allow us to minimize comorbidities.

Despite our decision to stop prostaglandin use before cataract surgery, there is no gold standard among clinicians on this issue, reflecting the absence of definitive evidence that prostaglandins really do cause CME. For now, each clinician has to make that decision. Further research into prostaglandin analogs' exact mechanisms of action may help elucidate the pathogenesis of CME and related complications, and allow us to better tailor our treatment algorithms to individual cases. REVIEW

Dr. Shrivastava is a glaucoma specialist and assistant professor of ophthalmology in practice at Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He has no financial interest in any product mentioned.

1. Hylton C, Robin A. Update on Prostaglandin Analogs. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2003;14:65-69.

2. Van der Valk R, Webers CAB, Schouten JSAG, et al. Intraocular pressure-lowering effects of all commonly used glaucoma drugs. Ophthalmology 2005:112;1177-85.

3. Ayyala RS, et. al. Cystoid Macular Edema associated with latanoprost in aphakic and pseudophakic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:602-604.

4. Yeh P, Ramanathan S. Latanoprost and clinically significant cystoid macular edema after uneventful phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surgery 2002:28;10:1814-18.

5. Schumer RA, Camras CB, Mandahl AK. Latanoprost and cystoid macular edema: Is there a causal relation? Curr Opinion in Ophthalmology 2000;11:94-100.

6. Henderson BA, et al. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:5:717-8.

7. Nguyen, Q. The role of prostaglandin analogues in the treatment of glaucoma in the 21st century. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2004;44:2:15-27.

8. Christiansen GA, et. al. Mechanism of ocular hypotensive action of bitamoprost in patients with ocular hypertension or glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2004:111:1658-1662.

9. Miyake K, et. al. ESCRS Binkhorst lecture 2002: Pseudophakic preservative maculopathy. J Cataract Refractive Surgery 2003:29;9;1800-10.

10. Wand M, Shields B. Cystoid Macular Edema in the era of ocular hypotensive lipids. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:3:393-97.

11. Kahook M, Noecker RJ. Comparison of corneal and conjunctival changes after dosing of travoprost preserved with sofZia, latanoprost with BAK, and PF artificial tears. Cornea 2008;27:339-343.

12. Schuman JS. Antiglaucoma medications: A review of safety and tolerability issues related to their use. Clinical Therapeutics 2000;22:2:167-208.

13. Bowling B, Calladine D. Routine reduction of glaucoma medication following phacoemulsification. J Cataract and Refractive Surgery 2009:35:3:406-407.

14. Asano S, et al. Reducing angiographic cystoid macular edema and blood-aqueous barrier disruption after small-incision phacoemulsification and foldable intraocular lens implantation: Multicenter prospective randomized comparison of topical diclofenac 0.1% and betamethasone 0.1%. J Cataract & Refractive Surgery 2008;34:1:57-63.

15. Wright PL, Wilkinson CP, Balyeat HD, Popham J, Reinke M. Angiographic cystoid macular edema after posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106:740-744.