When a patient is referred for cataract surgery, that might not be the only issue the cataract surgeon has to address. Quite often, corneal irregularities will reveal themselves in preop testing, unbeknownst to the patient, and subsequently alter the treatment approach. We spoke with cornea and cataract specialists who recommend careful assessments of individual patients to exclude any corneal irregularities, and if found, say you should determine whether to address them medically or surgically prior to cataract removal. Here’s their guidance on treatment and managing patient expectations.

Preop Testing

This phase of evaluation shouldn’t be rushed to ensure nothing is missed, but top-of-the-line technology, while helpful, isn’t always necessary.

It’s important to discuss what tests are covered by patients’ insurance, advises Kevin M. Miller, MD, who is the Kolokotrones Chair in Ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “If they’re planning cataract surgery, we put most of our patients through some sort of corneal mapping. We primarily use Scheimpflug devices, such as the Pentacam or the Galilei. You can also use a regular corneal topographer and pick up a lot of irregularities, and there are newer OCT devices that can also map out a cornea,” he says. “The thing is, you can’t just throw these screening tests at patients because insurance won’t pay for them. You have to make sure to let the patient know what will be covered and what will be out of pocket. Sometimes patients won’t opt for the extra testing and will just take their chances.”

Other times, it comes down to the basics. “For assessing the tear film, there are many helpful technological components to the dry-eye assessment these days but these can sometimes be prohibitively expensive to the smaller ophthalmic practices or to the patient,” says Tanya Trinh, MBBS, FRANZCO, who is a specialist in cornea, cataract and refractive surgery at Mosman Eye Centre and George Street Eye Centre in Australia, and a fellow of the World College of Refractive Surgery and Vision Sciences.

“A high-quality dry eye assessment is still very much in the hands of the surgeon with their ears primed for the patient’s clinical symptoms, their eyes focused at the slit lamp and the humble fluorescein strip in their hands. Tear breakup time and surface staining are incredibly useful as well as visually and functionally assessing the eyelids and their meibomian gland integrity at the slit lamp,” she continues.

“I teach all my residents and fellows to adhere to a systematic assessment of the tear film, corneal layers and ocular surface before moving beyond to other intraocular structures,” says Dr. Trinh. “I then encourage them to match up their clinical findings with topography and/or tomography as well as their biometric measurements to ensure that all of it makes sense. It’s not uncommon that something is missed on the clinical examination that the subsequent imaging is able to highlight and is useful for guiding any areas that you may need to take a second look at.”

After making sure the acquisition of each modality is of robust quality, Dr. Trinh encourages residents and fellows not to forget the basics, such as patients’ unaided and aided visual acuity, history of manifest refraction and stability, and assessment of the “match” between eyes in the same patient (keratometry, magnitude and axis of astigmatism, axial length matching between eyes and also with expected refractive status of the patient and more).

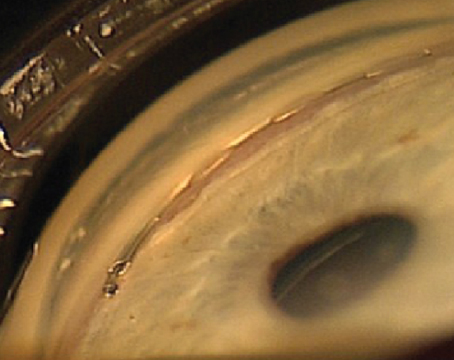

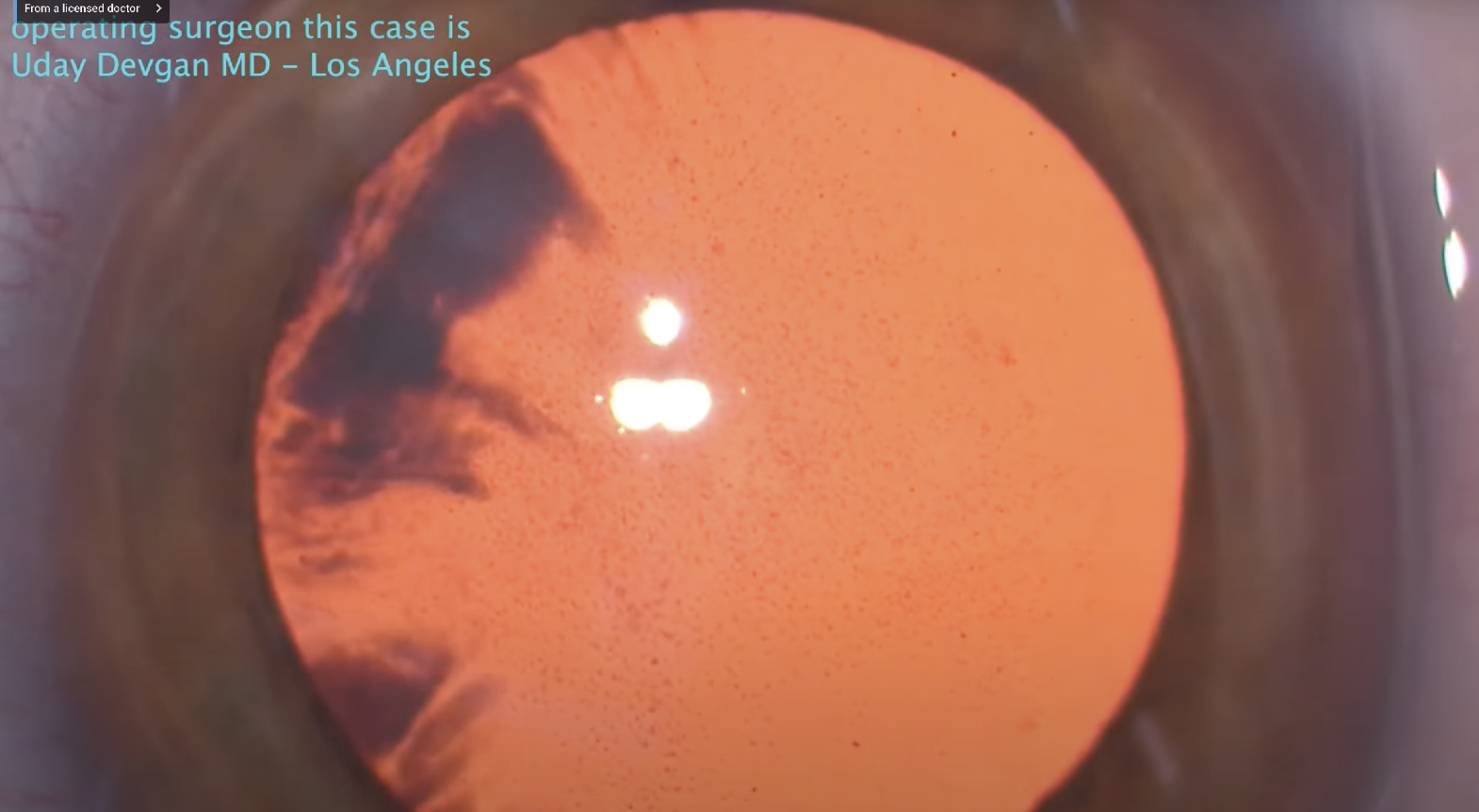

The presence of guttae in the cornea could signify Fuchs’ dystrophy. Although it may not appear as an irregular corneal surface, if it becomes more severe it can lead to severe irregular astigmatism and unreliable A-scan readings and IOL calculations. Depending on its severity, Fuchs’ can often be treated simultaneously with cataract surgery. Photo: Uday Devgan, MD. |

The (Ir)regular Suspects

Corneal irregularities come in a broad range, from the ubiquitous dry eye to the more rare Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy, and everything in between.

“The most common irregularity is dry eye, and then there are all kinds of corneal dystrophies, the most common being map-dot-fingerprint,” says Dr. Miller. “Then there are ectatic conditions, like keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration and post-refractive surgery ectasia. Then there are eyes where you can’t put a name on their condition but one or both corneas are irregular. Whenever I see someone for cataract surgery and they have a history of rigid contact lens wear, the radar goes off in my head because maybe they’re in rigid contact lenses for the reason that they couldn’t get good quality vision with glasses or soft contacts.”

Mark A. Terry, director of Corneal Services at the Devers Eye Institute in Portland, Oregon, says corneal scarring is another category to look out for. “Included in this category would be the iatrogenic scarring from abnormal LASIK flaps, decentered PRK ablations, and radial keratotomy,” he says. “Other common scars that can distort the corneal surface are pterygia, Salzmann’s nodules, and of course traumatic lacerations.”

Dr. Trinh says RK patients are becoming increasingly common as this patient group ages and develops cataracts, with special pre-, intra- and postoperative modifications required alongside careful preop counseling and extended close postop follow-up.

“The genetic/environmental disease of keratoconus is more commonly recognized today due to our improved diagnostic scanning devices such as the Pentacam,” Dr. Terry says. “The ectasia that results from keratoconus gives a characteristic irregular astigmatism that’s highly variable in amplitude and can be progressive. Identification of the presence of keratoconus is critical when considering surgery (such as cataract or refractive surgery) to avoid postop refractive surprises.”

Dr. Trinh says subclinical keratoconus or pellucid corneal changes may cause irregular astigmatism, requiring additional diagnostics and approach to lens selection and expected outcomes. “Frank keratoconus or pellucid patients who exist comfortably in hard contact lenses may warrant a separate discussion as to their lens choice and postop contact lens wear approach,” she says. “Patients who are post corneal grafting procedures also need special care as the risk of corneal graft rejection or failure needs to be pre-emptively monitored and managed.

If you’re a transplant surgeon, penetrating keratoplasty or deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty are common causes of irregular astigmatism, says Dr. Terry. “It’s rare for an eye following PK/DALK to not have some level of irregular astigmatism. While surgeons have tried various surgical solutions like suture technique variations and femtosecond laser-constructed complex wounds, the final topography after PK/DALK is largely determined by wound-healing dynamics, which the surgeon can’t control.”

There are some rare or unusual corneal irregularities that can be missed or that masquerade as dry eye.

“Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy is another common cause of differing or fluctuating corneal topographies,” Dr. Trinh says. “Changes reminiscent of the classic map-dot-fingerprint types are easier to diagnose, but often can be missed if subclinical. Surgeons should specifically lift the upper eyelid and look at the superior mid-peripheral region of the cornea as well as assess for reverse fluorescein staining patterns which can highlight the presence of subclinical disease.”

Salzmann’s nodular degeneration, conjunctivochalasis, pterygium, floppy eyelid syndrome, all can masquerade as dry-eye disease, says Karolinne M. Rocha, MD, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology and director of the Cornea and Refractive Surgery Division at Medical University of South Carolina, Storm Eye Institute. “Neurotrophic keratitis stage one looks like dry eye,” Dr. Rocha adds. “Checking for corneal sensitivity in the clinic is one way to test for that.”

Dr. Terry says to be cognizant of Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy, which causes progressive stromal edema. “This stromal swelling usually doesn’t result in an irregular corneal surface, but if the endothelial dysfunction is severe enough, then epithelial edema and bullae can occur, causing severe irregular astigmatism and unreliable A-Scan readings and IOL calculations,” he says.

Finally, post corneal refractive surgical patients are another expanding category, Dr. Trinh says. “Surgical scars may be minimally present or not present at all and patients will often ‘forget’ about these procedures and often will only reply in the affirmative when specifically prompted. It’s very easy to miss these patients and all cataract surgeons need to actively screen for these by history, exam and diagnostics.”

Cornea before Cataract?

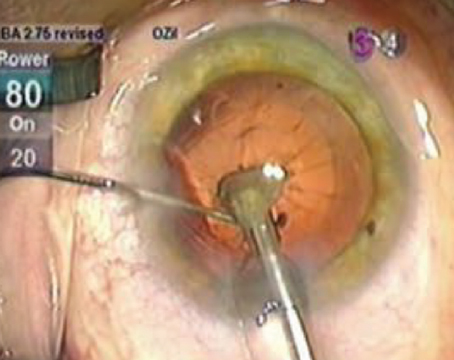

|

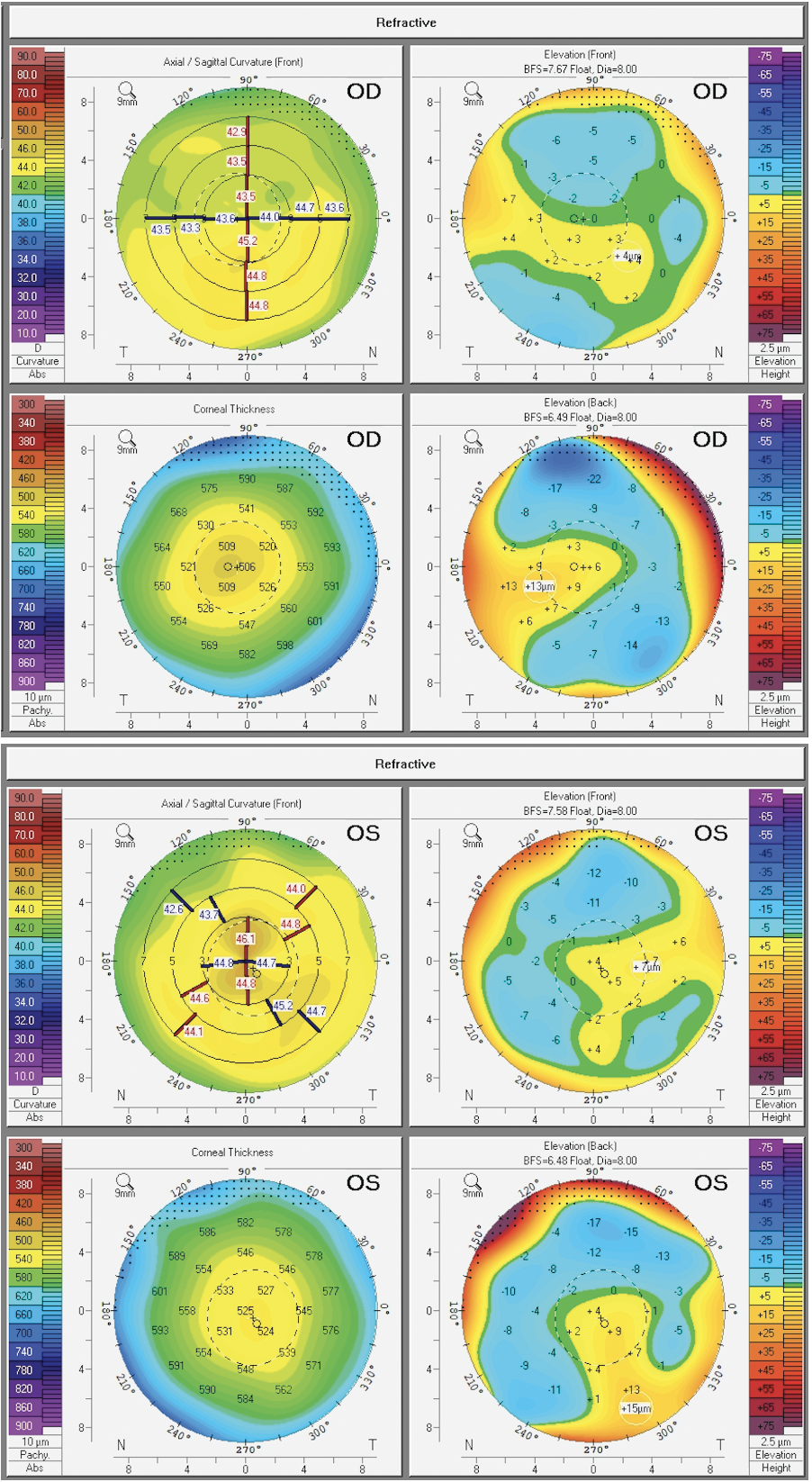

| (Top) Right eye of patient demonstrating changes consistent with keratoconus with inferior asymmetrical steepening, decreased corresponding pachymetry and evolving elevated posterior float. (Bottom) Left eye of same patient demonstrating changes consistent with the irregular tomographic changes of epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. Photo: Tanya Trinh, MBBS, FRANZCO. |

Now that you have discovered an irregularity that may interfere with the patient’s cataract plan, it’s time to decide how to move forward.

“If the surgeon is considering cataract surgery, then the surgeon has to ask the following three questions: Is that corneal problem currently detrimental to vision? Will it make the A-scan calculations less reliable? Will it be a problem postoperatively?” says Dr. Terry. “If the answer to any of these questions is ‘Yes’, then the surgeon needs to perform sequential surgery: correct the corneal problem first, allow healing until the surface is stable, and then proceed with more accurate A-scan readings for the cataract surgery.”

Patients may be thrown off by the fact that some other condition exists and may now delay their surgery.

“Some patients think that if they get their cataracts out, everything’s going to be good,” says Dr. Miller.

“But when you start doing some investigating and find irregularities, the question becomes: how much improvement will come from removing the cataract: 50 percent; 90 percent; or only 10 percent?” Dr. Miller continues. “If you think it’s only going to be a 10-percent improvement, you should probably be dealing with the corneal problem first. If you think you’re going to get a 90-percent improvement, then you can handle any symptomatic irregularity after.”

However, Dr. Miller says he generally feels it’s a bad idea to address corneal irregularity simultaneously with cataract surgery. “You either want to take care of it beforehand and regularize the cornea so you get the best lens power calculations, or you have a discussion with the patient about doing it after cataract surgery.”

“I explain to patients that irregularities can affect the measurements for the IOL and I try to remind them that cataract surgery is a one-time surgery and the lens will last forever,” says Dr. Rocha. “I make sure they understand how important the measurements are and that it’s worth waiting a few weeks to treat their condition prior to cataract surgery. I usually show them the picture of their topography map, and I feel patients appreciate that we’re not trying to rush.”

Dr. Terry says there are only two exceptions he would consider for simultaneous cataract surgery.

“First, if the patient is monocular with a severe cataract and requires a corneal transplant to reduce the irregular astigmatism or bullous keratopathy, then simultaneous PK/DALK is warranted to get the patient usable vision as soon as possible. This is especially true if the patient is a prior successful scleral contact lens wearer,” Dr. Terry says.

“Second, if the patient has endothelial dysfunction and there’s no preoperative irregular astigmatism, then simultaneous DMEK with cataract surgery should be done to avoid two trips to the operating room for these two separate problems,” he continues. “Our prior publications have shown that even toric IOLs can be used to accurately correct regular astigmatism in these Fuchs’ dystrophy patients. For those few patients that are unhappy with their postop visual acuity without glasses, then LASIK or PRK can be done to resolve their minimal residual refractive error.”

Dr. Trinh agrees, depending on the patient. “[Surgery to address] Fuchs’ dystrophy can be combined with cataract surgery and the prevalence of this combined procedure should ideally be influenced by the severity of the cataract and the endothelial dysfunction at the time of surgery,” she says. “Realistically however, these decisions can be further influenced by age and fitness for multiple surgical procedures if staged, as well as ease of access to the different healthcare systems and the local availability of corneal tissue for transplantation.

“In some cases, keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration may not require any treatment beforehand,” Dr. Trinh continues. “If the patient is proven to have stable mild keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration, their manifest refraction, topography and tomography match in terms of axis and magnitude and they see well (20/40 or better), I would be more inclined to proceed straight to cataract surgery and place a toric lens with a capsular tension ring in situ,” she says. “In cases where the cylinder component is less than 2 D, I may also be inclined to place a pinhole intraocular lens in the non-dominant eye and aim for a slightly minus refractive target to allow for some aided near vision.”

All of the sources we spoke with agreed that dry-eye treatment should begin prior to cataract surgery.

“It’s critical to actively diagnose and treat dry eye before accepting the final measurements for cataract surgery,” Dr. Trinh says. “In my practice, all patients receive a four-day course of fluorometholone and preservative-free tears prior to biometric measurements. Anyone with more moderate to severe dry-eye disease will be assessed and treated additionally preoperatively. This may even mean that their cataract surgery is delayed until the surface is adequately managed or at the best we can possibly rehabilitate.

“Because dry eye is often chronic, it’s also imperative that patients understand that their lenses will always work best with a well-lubricated eye, and even that some lenses will perform at a degraded optical quality in the presence of untreated dry eye,” she continues. “Severe dry-eye changes can also even be an automatic disqualifier for some types of lenses especially in the multifocal category, and patients must be counseled appropriately preoperatively about their expectations.”

Dr. Rocha says she tackles dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction prior to biometry measurements. “We can use Omega-3 EPA/DHA supplements, sometimes perform Lipiflow or iLux, and can start patients on medications such as lifitegrast or cyclosporine,” she says. “Sometimes I like to use topical steroids for two weeks to really treat that inflammatory component right away since we know that lifitegrast and cyclosporine can take a few weeks to work.”

In the treatment of EBMD and Salzmann’s nodules, it’s recommended to use superficial keratectomy before proceeding with cataract surgery. This can take approximately six weeks to heal before getting a normal surface topography, says Dr. Terry.

Dr. Trinh approaches Salzmann’s nodules and pterygia similarly, asking three important questions: Does this patient have progressive disease? Is there concurrent dry-eye disease that requires treatment? Does this patient require surgical intervention to remove the pterygia or nodules prior to cataract surgery?

“In cases where the disease process is actively progressing, near the pupil or causing irregular astigmatism, I will remove the pterygium or SND beforehand and allow the eye to settle for a period of a few months before recommencing measurements for cataract surgery,” says Dr. Trinh. “During the entire period, I will also ensure that ocular surface inflammation and dry eye is aggressively treated as standard; this will assist in minimizing chances of recurrence as well as optimizing the surface for future lens calculations.”

After superficial keratectomy (or another surface surgery), Dr. Trinh says she typically waits three months on average before cataract surgery. “However, the actual endpoint is seeing the stability of topographic changes,” she says. “So long as there’s not a concurrent rapid change in cataract progression, the manifest refraction may also assist as a guide alongside topographic evaluation.”

For the irregular astigmatism of corneal scarring, prior refractive surgery, and keratoconus, the decision of whether to fix the corneal problem first depends upon the level of distortion of the surface, says Dr. Terry. “If severe irregular astigmatism, and the patient can’t tolerate a scleral contact lens, then a corneal transplant (PK or DALK) may be warranted before the cataract surgery,” he says. “If the distortion isn’t severe or the patient has success with scleral contact lens wear and the cataract is the main cause of visual loss, then cataract surgery alone is reasonable. For the irregular astigmatism after corneal transplantation (PK or DALK), the astigmatism may be reduced with relaxing incisions and/or PRK prior to cataract surgery.”

Douglas D. Koch, MD, a professor and Allen, Mosbacher and Law Chair in Ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, says he would consider a scleral contact lens if the patient wasn’t eager to undergo a surgery to address the cornea irregularity. “I would tailor my discussion with the patient about getting close with a lens implant and then finish it off with a scleral lens, and I might have them fit for the scleral lens or see what it’s like before the surgery in order to be sure that’s a reasonable option,” he says.

IOL Calculations and Options

Our experts offered some insight into the factors that would influence their decision on IOL choice.

First, in power calculations, Dr. Miller says it’s tough with any irregular cornea to figure out the true corneal power in the central 3 mm optical zone. “I think it’s helpful to have some sort of corneal map and look at not just simulated K readings, but also look at the numbers that you see in the central 3 mm and maybe come up with an average number for the corneal power,” he says.

Dr. Koch looks at the central 3 to 4 mm and the power across various meridians opposite 180 degrees. “If the power is fairly the same, say 39 on one side and 40 on the other, then I’m more comfortable proposing a Symfony lens or maybe even a trifocal if it’s really uniform,” he says. “On the other hand, if it’s 39 on one side and 35 on the other, then I know there’s a lot of irregular astigmatism and that guides me toward a monofocal IOL.”

He adds that he does use the IOL calculations from the ASCRS website for corneas pertaining to post-RK or post-LASIK, for example.

As Dr. Terry says, every surgeon has their own preferred calculation formula. “Two of the most common are the Barrett and the Barrett Universal formula and I think those are excellent,” he says. “I think the hardest situation for these formulas to be accurate is in cases of radial keratotomy eyes and eyes with highly irregular astigmatism from other forms of corneal scars. But RK has always been one that has been difficult for any of the formulas to show the degree of accuracy they do with other forms of irregular astigmatism. I use the Barrett formulas for determining most of my IOL choices.”

Post-refractive surgery patients will also require differences in preoperative evaluation, says Dr. Trinh. “Higher order aberrations induced by some forms of refractive surgery may cause unexpected and undesirable visual phenomena postoperatively and limit the choices of lens technologies available to them,” she says. “The challenges with IOL power predictions also require reflection and adjustment with biometric formulas designed for these subgroups. Generally, traditional lens formulas will result in a hyperopic surprise when applied to patients with past myopic correction and a myopic surprise in patients who have had past hyperopic correction.”

Some surgeons have strong opinions about placing toric IOLs in patients with irregular corneas.

“I think that one of the biggest choices that surgeons have is whether or not to put a toric IOL inside the eye to correct astigmatism,” says Dr. Terry. “The more regular the astigmatism is, the more I’m in favor of toric lenses and the more irregular the astigmatism is, the less I’m in favor of them. So there’s a very black-and-white area on both sides and there’s a gray area in the middle.

“For instance: I would place a toric IOL into a keratoconus or PK eye that has mild irregular astigmatism that’s stable and has no prospects of a corneal transplant or scleral contact lens use in the future,” Dr. Terry continues. “I wouldn’t place a toric IOL in a keratoconus or PK eye that has highly irregular astigmatism, with shifting axis and with successful scleral contact lens use in the past. Therefore, placement of a toric IOL is something that has to be really individualized to the patient’s circumstances.”

Dr. Miller says he is hesitant to use toric lenses in any eye with corneal irregularity. “Too often I see papers published with great one-year results after a toric lens goes into an eye with a corneal transplant,” he says, “then 10 years later the astigmatism has completely changed and now the toric lens isn’t helping them. I might even be hurting them. Be cautious about putting toric lenses into eyes with irregular corneas.”

Like most surgeons, Dr. Terry doesn’t recommend multifocal IOLs in any eye with irregular astigmatism. “Multifocal IOLs require minimal to no astigmatism postoperatively to be effective and acceptable to the high standards of patients receiving these lenses,” he says.

In general, Dr. Koch is conservative and tends to go with a monofocal IOL. “I’ve had some good luck with the Symfony and its new Opti-blue version in post-LASIK patients, but if there’s much irregularity in the cornea I avoid multifocal or EDOF lenses,” he says.

Dr. Koch and others are particularly excited about the Apthera IC-8 and how that will change conversations with patients. “I think, as an off-label use, this lens will be a very useful tool for getting these patients better quality vision and more accurate refractive outcomes,” he says.

Dr. Rocha, who is also looking forward to possibly using the Apthera IC-8, feels that after these patients’ ocular surface has been treated, they’re in fact candidates for EDOF, trifocal or hybrid multifocal EDOF lenses, depending on the case.

“You have to consider, is their irregularity a condition that you can treat and then the patient is good, or is it a progressive disease?” she says. “Will the cornea continue to change shape? Yes, in some conditions, for example progressive keratoconus. In those cases, you need to be conservative and consider monofocal IOLs. But if someone had a small scar or nodule and you did a PTK with laser and now the cornea looks regular, that patient can benefit from some of the presbyopia-correcting lenses or the small-aperture optics.”

Patient expectations should be managed along the way, says Dr. Trinh. In someone with Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, the surgeon should help the patient understand the natural pathophysiology of the disease, balancing the severity of the cataract against the severity of the endothelial disease. “Because there’s a statistically higher chance of endothelial failure in this group of patients, the choice of lenses used may also be affected,” she says. “For example, patients desiring spectacle independence may choose to avail themselves of monovision options rather than using multifocal technologies.”

Dr. Trinh highlights another specific scenario for keratoconus or pellucid patients (or any patient with higher irregular astigmatism such as corneal grafts) who enjoy wearing their hard contact lenses and have the dexterity to continue doing so. In this situation, she’ll generally place a non-toric IOL and allow the contact lens to address the irregularity of their astigmatism. “This will always give the best quality of result in terms of vision,” she says.

Dr. Miller dreams of postop power adjustable lens technology that could be tweaked, not just for sphere and cylinder, but also higher-order aberrations. “This may be our best way of dealing with eyes that have irregular corneas,” he says. “If you could counteract the distorted wavefront of the cornea by compensating with a counter-distorting wavefront on the lens, maybe we could get really good quality vision for these patients. One of the long-term problems with irregular corneas is they tend to change over time. So if you had such a technology, it would have to be continuously adjustable to be truly beneficial.”

Parting Advice

The best way to prepare for these irregularities is to approach each patient with a suspicion for them, advises Dr. Miller. “They’re very common and you can’t always look through a slit lamp biomicroscope and see it,” he says. “It helps if you have a way of mapping every person who comes through. When you only map the people who opt for premium lenses, that’s where you’re going to get burned. If you discover a problem after surgery, then you caused the problem—that’s what the patient will think. You can’t tell them it was probably irregular before surgery if you don’t have a picture to prove it. You must have a system for detecting things systematically.”

Dr. Koch consults for Alcon, Bausch + Lomb, Johnson & Johnson and Zeiss. Dr. Miller is a consultant for Alcon, BVI, Johnson & Johnson Surgical Vision, Long Bridge Medical and Oculus USA. Dr. Rocha, Dr. Terry and Dr. Trinh report no relevant disclosures for this topic.