Probably not since the first wave of femtosecond lasers designed for use in LASIK has there been so much discussion of the potential and drawbacks of a technology as there has been with femtosecond cataract surgery. In this month’s e-survey on cataract technique, surgeons get to voice their opinions on the technology, from votes of support for it as the wave of the future, to questions about its clinical outcomes and financial viability. Also, surgeons take time out from the femtosecond fray to weigh in on other cataract topics, such as their favorite techniques, maneuvers and anesthesia methods.

These are just some of the findings from this month’s e-survey on cataract surgery. The e-mail survey was opened by 1,275 of 10,000 subscribers to Review’s electronic mail service (13 percent open rate), and of those, 173 (14 percent) responded. To see how your techniques compare with theirs, read on.

Femtosecond-assisted Surgery

On the survey, 8 percent of the surgeons currently perform femtosecond-assisted cataract surgery. R. Wayne Bowman, MD, from Dallas says he appreciates the laser’s “consistency and accuracy,” and a surgeon from Minnesota feels similarly, saying he likes its “improved reproducibility,” but cites “cost and learning curve” as less desirable aspects. “I love it,” says Norfolk, Va., surgeon John Sheppard.

“However, removing sub-incisional cortex is more difficult, and it is costly and more time-consuming. There are safety advantages due to better wound healing, less phaco time and a stronger capsulorhexis edge, and it’s great for promoting and growing the practice.” Los Angeles surgeon James Salz also accepts the good with the bad with his femtosecond laser. “I love the rhexis, arcuate incisions and chopping,” he says. “I do not like it for primary and side-port incisions as I prefer to place them exactly where I want them [more limbal] and the femto incisions are usually off my preferred location, as it makes the incisions more corneal.”

|

|

Looking ahead, 70 percent of surgeons say they’re unlikely to perform femto-assisted surgery in the current year. However, 21 percent think they’re somewhat likely to do so, and 9 percent say they’re very likely to perform it. At this point, uncertainty reigns, as many surgeons find it hard to justify pulling the trigger on the technology. “The femtosecond laser and phacoemulsification machine are separate technologies utilized in separate theaters,” says a surgeon from Texas. “I feel this is inefficient surgery, and anticipate the technology will someday merge into a single unit or platform with aspiration handpieces optimized to remove a pre-segmented nucleus. Also, the current standard monofocal intraocular lens results are good enough as to not justify the capital investment or recurring click fee for the femtosecond laser.” A surgeon who wished to remain anonymous says the financial hurdle is still the major sticking point. “The laser still costs too much,” he says. “Despite being in a surgery center with 15 operating physicians, we cannot make the numbers work at this time. Until insurers start to cover the cost—at least partially—or until manufacturers drop the price, femto cataract surgery is going to be a boutique item.” Luther Fry, MD, of Garden City, Kan., says, “There’s no benefit, it’s expensive and more than doubles my surgical time.” Ben Mackey, MD, of Corbin, Ky., says he’s unlikely to do it. “My surgery center cannot justify the expense,” he says. “And I cannot justify the expense and anticipated slow down.” David Brigham, MD, of Des Peres, Mo., adds that lens technology may hurt some of the need for the femtosecond. “The prospect of the toric multifocal IOL coming soon to the United States will make astigmatic keratotomy less necessary in premium cases,” he says. “There will be less incentive to use the femto in other types of IOL implantation as it will increase the time and the cost of each case. I really think most patients are cost-conscious and are reluctant to spend out of pocket, especially those over 80. Younger people in their 60s and 70s are easier to convince about the benefits of premium lenses, and it follows that they would be the best candidates for the femto laser—but the $750 extra will take a little more salesmanship.”

There are also cataract surgeons who don’t use the femtosecond laser at the moment, but see the device as the future of cataract surgery and would rather be on the train than under it. One surgeon from Tennessee says he’s likely to use it due to the “demands of the market.” A surgeon from Ohio is eager to do it, even saying, “I might change jobs to a location where it’s available.” A surgeon from Tennessee doesn’t want to get left behind. “You have to keep up with the Joneses!” he says. “I believe the future of cataract surgery will involve some version of these lasers, and we need to keep up with the technology.”

Fighting Infection

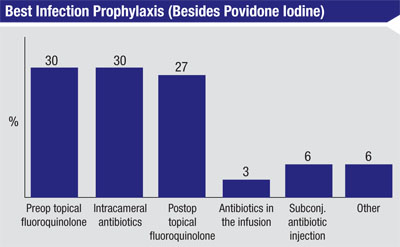

When it comes to the best infection prophylaxis method, in addition to the use of povidone iodine, 30 percent think preop topical fluoroquinolones are best, 30 percent prefer an intracameral antibiotic injection and 27 percent like postop topical fluoroquinolones. Less popular are subconjunctival antibiotic injection (6 percent) and the use of antibiotics in the infusion (3 percent). Another 6 percent choose some other type of prophylaxis. Some surgeons chose more than one option.

“I use topical fluoroquinolones,” offers Mark Volpicelli, MD, of Mountain View, Calif. “And I also use an intraoperative injection of vancomycin at the end of the procedure.” Another surgeon says he thinks “an immediate postop Betadine drop” is best. Lan Pham, MD, of Yorktown Heights, N.Y., combines approaches, saying, “I prefer pre- and postop topical antibiotics, as well as great, well-sealed corneal incisions.”

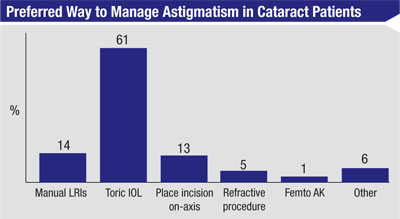

Controlling Astigmatism

Most of the surgeons, 61 percent, prefer to manage a patient’s astigmatism with a toric IOL. Fourteen percent like manual limbal relaxing incisions, 13 percent prefer placing the clear corneal entry wound on the axis of astigmatism, 5 percent think a postop refractive procedure is best and 1 percent perform femtosecond astigmatic keratotomy. Six percent choose some other method, including postop spectacles.

|

|

In the LRI camp, Michael Sala, DO, of Erie, Pa., says, “They’ve given me good results for years,” and a surgeon from Washington agrees, saying, “They’re less reliable, but they’re cheap and easy to do.” Donna Qahwash, DO, of Wyandotte, Mich., says she prefers doing LRIs to other methods because “They represent less cost to the patient.”

Cataract Techniques

Surgeons also discussed various other aspects of cataract surgery, from nuclear fragmentation to bimanual surgery.

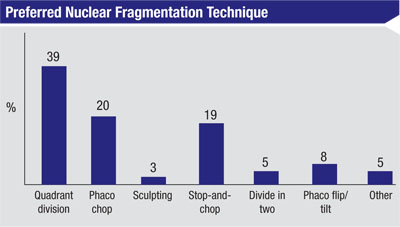

• Fracturing the nucleus. When surgeons attack the nucleus, 39 percent prefer to do it with quadrant division; 20 percent like phaco chop; 19 percent prefer a stop-and-chop maneuver; 8 percent like phaco flip/tilt; 5 percent divide the nucleus into two halves first; and 3 percent like sculpting maneuvers. Five percent say they like some other approach.

“With quadrant division, most of the phaco energy is exerted posterior to the level of the iris and a greater distance from the corneal endothelium,” says a surgeon from Delaware on why he prefers the method. A surgeon from Louisiana also likes quadrant division. “It’s easy to manage,” he says. “I was not taught phaco chop and feel more comfortable with quadrant division, and have very few complications.” A surgeon from California concurs, saying, “For me, quadrant division is safest in that it exerts less zonular traction and is the most efficient, time-wise.”

However, the proponents of phaco chop say that in the right hands, it has a good safety profile, too. “Phaco with a vertical chopping technique minimizes ultrasound time and poses less risk to the capsule,” says Bruce Hodges, MD, of Frederick, Md. Kentucky’s Dr. Mackey says, “Phaco chop is usually more efficient than other techniques. It’s less dependent on pupil size, also.” Dr. Moore agrees, saying the features he appreciates most about chopping are “Efficiency, adaptability, safety and decreased energy.”

The stop-and-chop proponents think it’s preferable to the other approaches, however. “It’s easy, consistent and quick,” says a surgeon from California. Dr. Mamalis says that with stop-and-chop he gets “good control of the nucleus during phaco with an initial groove.” A surgeon from California agrees, saying, “The central groove clears out some space centrally so that it’s easier to chop the remaining half and bring the piece into the middle for removal.” Patrick Chin, MD, of Westwood, N.J., says that stop-and-chop “allows me to disassemble the nucleus easily and consistently for all types of nuclear densities and minimize the use of phaco energy.”

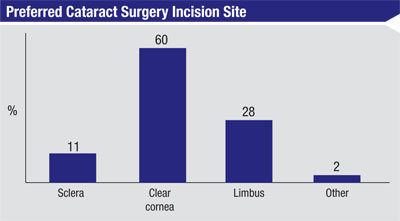

• Incision location. Sixty percent of surgeons use clear corneal wounds, 28 percent prefer limbal, 11 percent use the sclera and 2 percent use some hybrid of those. The average incision size cited was 2.56 mm.

Dr. Salz says he prefers using the limbal region. “The wound is near-clear, with a vertical groove of 3 mm and an entry incision of 2.75 mm,” he says. “I like to make the groove in the limbal arcade so it bleeds slightly, as I think you get faster healing at that location.”

• Bimanual and C-MICS. A bimanual technique in which the infusion and aspiration are done through separate handpieces has only caught on with 20 percent of surgeons. Respondents offer a variety of reasons why it hasn’t worked for them. “I don’t find that chamber stability is as good as micro-coaxial and since my wound will have to be enlarged, there is no benefit,” says New Jersey’s Dr. Chin. However, Louise Davis, MD, of Beverly Hills, Calif., prefers bimanual, saying, “It’s the safest for the capsule.”

Another alternative technique embraced by some surgeons (35 percent on the survey) is coaxial micro-incision surgery, or C-MICS. “It makes for safer removal of the lens,” says a surgeon from Louisiana. “It also provides good anterior chamber stabilization.” However, some surgeons point out that such small-incision techniques don’t keep the incision small throughout the entire case. “There’s no distinct advantage at this time in terms of safety or efficacy since the incision size is expanded to allow IOL insertion,” says a surgeon from California.

• Best practices. Surgeons also shared the tips and techniques they’ve developed to make procedures run more smoothly and be more successful. “The continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis is the most important part of the cataract surgery,” says Dr. Mamalis. “Take the time to perform a well-centered, properly sized CCC and the remainder of the case will proceed more smoothly.” Dr. Sheppard has several tips, and says a relatively mundane surgical maneuver can actually prove to be very useful. “An unheralded way to prevent post-cataract endophthalmitis is a very thorough I/A of the viscoelastic at the conclusion of the case: It dilutes organisms to manageable titers,” he says. “Also, use dispersive viscoelastic on the endothelium before phaco to preserve corneal thickness, know that every patient is a candidate for a premium IOL until proven otherwise and treat every patient as if he or she were your dad or mom.” Sandy Yeh, MD, of Springfield, Ill., has a neat tip for streamlining the surgery day: “We include dilating drops in the patients’ surgical kits for them to use to self-dilate the morning of the surgery,” she says. “They arrive at the ASC fully dilated and ready to go. This saves a great deal of nursing time, and if one patient isn’t ready the next will be ready to go. Also, in order to create a 5-mm capsulorhexis for a premium lens, mark the cornea with a 6-mm PRK marker and then target the capsulorhexis inside of this.”

In the end, surgeons say an experienced mind is the most valuable piece of technology. “Think,” advises Warren Cross, MD, of Houston. “If anything seems even slightly strange, stop, look and think for a minute—because after 50,000 cases something probably is different or wrong, even if it’s not obvious. Trust your instincts.” REVIEW