When managing glaucoma, there are a number of reasons ophthalmologists conduct tests. One is to establish a baseline so that later it is possible to determine whether something has changed. Another is to see if anything is “wrong.” Some tests are performed when trying to find a specific problem, such as a specific diagnosis. Other tests are done to compare with earlier tests, to determine whether there have been changes . Tests may also be done when they are of marginal value because they result in a reimbursement, or for the intent of protecting oneself from medical/legal concerns about not doing enough.

The information obtained from tests is often essential in order to decide what the patient has and what needs to be done. But testing also is expensive, inconvenient, and may actually be counterproductive. My hunch is that at the present time we probably do far more testing than is justifiable or helpful.

When trying to be of help to a patient with glaucoma and deciding upon what tests to do, it’s useful to consider two questions: Is this test really necessary? And, which tests are really worth doing?

Visual Fields: Not Always Helpful

Glaucoma is a disease that affects vision, so knowing what’s happening with the patient’s vision and understanding the nature of the visual field is often an important part of caring for a patient with glaucoma. There are many ways to evaluate the visual field; a standard automated perimetry is only one of them. The tests are subjective, however, and they are often difficult for patients to perform. As a result it is not rare to have false positives or false negatives.

One situation in which a visual field examination may be wasteful is when the test is performed in a person in whom it is virtually certain that the field is going to be normal. When the patient has no symptoms, no suggestion of the presence of glaucoma and a healthy optic nerve head, what is the benefit of obtaining a visual field? It will certainly be normal.

In contrast, a photograph of the optic nerve head can be extremely useful as a baseline because optic nerve heads come in many different shapes, sizes and colors; in order to see a change in the optic nerve head, it’s often necessary to know what it looked like to start with. The same is true for a gonioscopic examination. But this isn’t true for visual fields, where you’re looking for the development of a defect. (One potential advantage of a baseline visual field is that the patient can learn how to take the test, which does have some value.)

Besides being costly, time-consuming and inconvenient, visual fields can also be misleading. Bal Chauhan, MD, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, has done excellent work on the issues surrounding visual field testing. He and others have suggested that, because of the variability of the results, it may be necessary to perform up to six visual fields before you can tell that a change has definitely occurred. In order not to miss something that’s happening along the way, that would mean performing a visual field every two months or so. In the first place, doing that for every patient would be very expensive. Second, that large number of tests would be associated with some false positives. As many as one out of five test results might incorrectly indicate that the patient had gotten worse.

It’s often difficult to determine whether a change in the field which is considered definite by the testing machine really is definite. (For example, consider the series of fields shown above.) When the physician or optometrist sees a visual field that definitely appears worse than previous tests, and the patient asks if her visual field is worse, the answer could be, “Yes, I think it’s worse,” or, “I really can’t tell because visual fields are noisy; I can’t determine whether you’re actually worse or not just on the basis of this field.” Meanwhile, however, the patient is impressed that the test looks worse. So what is the doctor to do? He’ll probably increase the vigor of treatment by adding another drop or perhaps moving to surgery. This is not ideal because every treatment—without exception—causes side effects. If the patient really hasn’t gotten worse, increasing the treatment is likely to make her worse unnecessarily.

The bottom line is that it’s advisable to reduce the number of tests to the point where you have as few false positives and negatives as possible, and tests are only done when they are really necessary.

My prediction is that 10 years from now, visual fields will be used less than they are now. They are difficult for the patient and variable. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study measured visual fields to determine whether the enrolled subjects were getting worse. They found that of the visual fields indicating that the patient had worsened, 86 percent were invalid—that is, the patients had not actually worsened.

So: How often do you need to do a visual field on a glaucoma patient? There is no simple answer. Some guidelines say that visual field examinations should be done every year, but I disagree with that. If a glaucoma patient has been stable for, let’s say, five years, and there is no indication of concern because his pressure appears to be in a range that’s been associated with stability of the disc and field for those five years, and the disc is quite healthy looking,

I see no reason to get a visual field on a yearly basis. Why subject an asymptomatic patient to a test that costs a lot of money, takes up the patient’s and technician’s time, and will probably give a result that’s unlikely to alter the way the patient is being cared for?

On the other hand, when patients are unstable and appear to be progressing rapidly, it may be necessary to test them at intervals as short as several months. The appropriate frequency of tests needs to be individualized to be most appropriate for the person being taken care of.

High-tech Testing

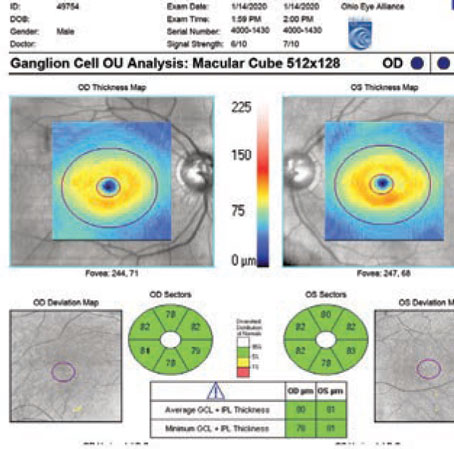

What about the newer imaging techniques that are available—OCT, HRT and GDx? Our group conducted a study on this, and we found that about half of the time you can’t really interpret the results. The scan may not be quite in focus, or the focus is fine but you simply don’t know what to make of it. That’s a lot of money to be spending if a significant number of the tests you’re doing are going to end up in the wastebasket. Even worse, if a test result is hard to interpret and you interpret it anyway, you’re likely to end up with a result that’s not valid, leading to incorrect treatment.

Certainly if you see a reason to suspect that the test won’t work for some technical reason, such as that the patient has trouble keeping his eyes still or you can’t dilate the pupils well for a test that requires dilation, for goodness sake, don’t do the test. It won’t give you any valid information; all it will do is cost money and take time. Maybe you’ll get some kind of barely interpretable result which you then try to interpret, which is worse than having no data at all if it leads you to an invalid conclusion.

Some have argued that these high-tech scans are very useful. However, it’s hard to understand why these tests went from being not useful to being useful simply because they went from being non-reimbursable to being reimbursable.

Measuring central corneal thickness has also become very popular; it’s now routinely done on most patients who have glaucoma. In theory it can provide some useful information, but the person who really brought the potential importance of CCT to our attention—James Brandt, MD—makes the point that there’s currently no algorithm that can be used to accurately adjust a patient’s intraocular pressure on the basis of corneal thickness. Without the ability to make that correction, why do the test?

One reason for measuring CCT that may make sense is for the purpose of accumulating data that might help develop future uses for this data. There’s evidence, for example, that people with thin central corneas may be at greater risk for developing glaucoma. If that’s true, then measuring central corneal thickness might provide information as to whether a person with glaucoma is going to get worse or not. That would be valuable, so collecting data in a way that would help answer that question is important.

In fact, collecting clinical data that can be used in research can often be accomplished just as well in a private practitioner’s office as in an academic glaucoma center. A private practitioner who can say, “I’ve now got 1,000 CCTs and I found that there was a very close correlation between thinness of the cornea and the likelihood of a person developing progressive glaucomatous visual loss,” is making a real contribution.

AS-OCT vs. Gonioscopy

Some surgeons have argued that anterior segment OCT is a good source of information regarding the condition of the angle. It does provide an objective measurement, which sounds great. The problem is, what can be done with that objective measurement? There isn’t enough information available yet to use AS-OCT in the same way data uncovered by gonioscopy can be utilized.

A gonioscopic exam, for example, can reveal that there is blood in the angle, triggering an appropriate evaluation to figure out why. Gonioscopy can show a tear in the angle, indicating there was previous trauma. Or it can reveal that there is a Sampaolesi line or increased pigmentation of the posterior trabecular meshwork, triggering the likelihood of a diagnostic entity. AS-OCT will not show any of those attributes.

AS-OCT does indicate the angle configuration, and that’s important, but how to translate that angle configuration into clinical care is not yet clear. Furthermore, because it’s often difficult using AS-OCT to determine exactly where the trabecular meshwork is, it’s hard to determine whether the angle is actually closed or not.

Patients would be better served if ophthalmologists gonioscoped their patients knowledgeably rather than depending on AS-OCT. Gonioscopy takes about a minute, in contrast to perhaps a half hour for an AS-OCT. Gonioscopy doesn’t require an expensive machine; a gonioscopic lens can be carried easily in the pocket. Technicians are not required for gonioscopy, and patients don’t need to go to another room or facility to have the test. Overall, AS-OCT currently increases the inconvenience to the patient and the cost of care, without any evidence that it actually improves patient care. Admittedly, gonioscopy is not easy to master, but it has been shown that it can be learned, and studies have demonstrated that it can be highly reproducible.

Should ophthalmologists skip using AS-OCT altogether when managing glaucoma? In my opinion, yes. Patients can get the very best care available without it. (A possible exception might be certain cases in which the cornea is cloudy, where some physicians might find the information helpful.) The technique needs to be studied; we need to learn about it. But as far as managing today’s patients, in general I don’t believe it should be used.

The Downsides of Testing

One of the most important reasons to avoid unnecessary testing is the cost. The simple fact is that medical care has become unaffordable in the United States.

I recently got a brace for an injury; it was very expensive, and it didn’t work very well. I went back to have them adjust the brace; they filed down one part of it and made a few adjustments and then charged $776 for the adjustment. My thought was, if you didn’t get it right the first time, you shouldn’t be getting paid extra to fix it. With this arrangement, they can charge every time it needs adjusting, which gives them an incentive to never get it right! Medical care can’t work like that; it’s not sustainable.

Another problem is that many tests are conducted simply to protect the doctor from being accused of over-looking something. This is one of the most misused justifications for doing a test—and it backfires in the long run.

Suppose an ophthalmologist decides to do a visual field, not because he thinks the field will be abnormal, but out of fear that if he doesn’t do it and misses something he might be liable later on. This has serious unintended consequences, because standard of care is determined by what doctors do. If you perform tests even though you don’t really think they’re necessary, you’re developing a standard of care that says these tests should be done. You’re locking yourself into having to do them in the future.

Some may think that doing “defensive testing” will protect them for the moment, but physicians have also been successfully sued for performing unnecessary tests. Excessive testing, is really self-defeating, because it sets up unrealistic standards. (It’s difficult to defend oneself for not having done an unnecessary test if everybody else in the profession is doing it.) And when the standard of care involves doing unnecessary tests, that drives up the cost of care significantly and unnecessarily.

Please don’t misunderstand me; I’m not opposed to testing. In fact, I think we should be doing more testing in certain areas, such as obtaining baseline photographs of the optic disc and evaluations of the anterior chamber angle, than we’re doing now. But much of the other testing being done is unnecessary and even counterproductive, and it adds to the unacceptably high cost of medicine.

Getting a Good Baseline

Glaucoma is a process, and one of the ways in which the glaucomatous process manifests itself is by the optic nerve head becoming damaged. In the early stages of glaucoma, probably the best way to determine that the process is active is to see that the optic nerve is changing. The detection of damage, however, often requires the presence of a baseline to determine whether the current appearance is merely a variation from normal or actually represents a change from the earlier appearance.

For this purpose, obtaining a baseline optic disc photograph is highly useful. One of the problems with obtaining baselines with tests such as OCT, HRT or GDx is that the technologies change frequently, so that data obtained 10 years hence may not be able to be compared meaningfully with data obtained 10 years before. On the other hand, disc photographs that were taken when photography was in its early stages are just as valid now as they were then. Even an accurate disc drawing, such as those made by Austrian ophthalmologist Eduard von Jaeger in 1869, are valuable pieces of information.

The second test that makes sense in order to establish a baseline is gonioscopy. Of course, the gonioscopic findings need to be recorded in a way that will provide needed information years later; that will make it possible to reasonably determine whether the angle has or has not changed.

Sadly, evaluation of the optic disc and gonioscopy are still not routinely done, even in patients with glaucoma. Several years ago, ophthalmologist Paul Lee, MD, noted that around 50 percent of patients who had glaucoma didn’t have comments on their charts as to the nature of the optic disc.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if disc photographs could be obtained on everyone? For example, it’s feasible to set up a system so that when people have their photographs taken for their driver’s license, a photograph of the fundus is also obtained. That photograph could then be encoded on the license in digital form. What a marvelous baseline that would be for understanding the health or disease of that particular eye years later.

Dealing With Current Reality

When it comes to caring for patients with glaucoma, it seems clear that we need better tests than the ones we have available now. There are excellent reasons to develop better objective digital imaging technologies, despite their current limitations with regards to being of help to patients. Were it possible to determine with certainty that the retinal nerve fiber layer was thinning, and the rate at which it was thinning, ophthalmologists would have a powerful tool that would help them determine whether their patients were getting worse. Meanwhile, other objective tests are also improving. One that I think needs to be carefully studied involves an objective way of detecting an afferent pupillary defect.

Glaucoma can be a really bad disease. If necessary treatment is not initiated in a timely fashion because a change in the retina or field was missed, the person may get worse unnecessarily. So I’m not saying that patients should not be tested—especially when establishing a baseline, where optic disc photographs and gonioscopy can be crucial. But before a test is ordered, we need to ask ourselves: 1) “Is this likely to give me a valid, interpretable result?” And 2) “Is the result likely to influence what I’m going to do with this patient?” If those two questions cannot be answered in the affirmative, maybe the test shouldn’t be done.

Dr. Spaeth is attending surgeon at Wills Eye Institute in Philadelphia and Louis J. Esposito Research Professor at Wills Eye Institute/Jefferson Medical College.