Sooner or later, most people need cataract surgery. That includes glaucoma patients, but their disease complicates matters; these patients need extra care both before, during and after surgery. In addition, some positive side effects of cataract surgery usually seen in healthy eyes, such as a drop in intraocular pressure, may not always appear when a patient is being treated for glaucoma.

Here, I’d like to discuss some of what we’ve learned about performing cataract surgery on patients with glaucoma, including what kind of pressure change you might expect the cataract surgery to produce, and the steps a clinician should take to ensure the best outcome in this situation.

Is a Pressure Drop Likely?

Although the evidence suggests that cataract surgery is likely to reduce IOP somewhat in a healthy eye, the evidence is far less clear for glaucoma patients. A few studies that have looked at this question have indeed found a reduction in the number of medications needed by glaucoma patients following cataract surgery.1-3 The problem is that this data is of varying quality—especially the baseline IOP data—and all of the studies are retrospective in nature. Most used a single IOP measurement before surgery to define the baseline, which subjects all subsequent analyses to regression to the mean, and postop measurements were not masked. Furthermore, in most of these studies the use of medications was not controlled. That means the data is subject to significant potential bias.

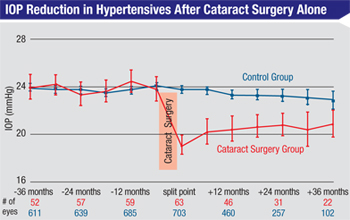

The highest-quality data we have regarding the isolated effect of phaco on lowering IOP in patients with higher-than-normal IOPs comes from the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Half of the patients in the OHTS were being treated with glaucoma medications; however, the published analysis relating to the effect of phaco on IOP didn’t include those patients. In order to look at the isolated influence of phaco, Steven L. Mansberger, MD, and colleagues at Devers Eye Institute in Portland, Ore., only evaluated the patients who were not on medications.4 (Those patients were not being treated because they showed no evidence of visual field or optic nerve damage at the time, despite their elevated pressures.)

|

Also of note, the data from the OHTS study, as well as the others already mentioned, showed that the strongest predictor of a significant IOP drop after cataract surgery was a higher starting IOP. One study, for example, found that patients with starting IOPs in the upper 20s experienced a six-point drop in IOP, on average; patients with a starting IOP in the upper teens only showed a 2.7-mmHg drop in pressure.3 Other published papers have confirmed this finding.5

Of course, most patients coming into cataract surgery with a known diagnosis of glaucoma are already on treatment, so using that data to guide clinical practice with a glaucoma patient is fraught with peril. However, I did have personal experience with many of the other OHTS patients—

the patients using glaucoma medications who underwent cataract surgery. After we did phaco, I gave them a drug holiday before reintroducing their glaucoma medications to see how much pressure-lowering the phaco provided.

My purely anecdotal experience was that their pressures did tend to drop a little; the majority of ocular hypertensive patients on treatment were able to stay off medications and still achieve the OHTS-specified 20-percent IOP lowering for about a year. But after a year, most of them had to go back on medication to reach the OHTS-defined target. This supports the conclusion that pressure-lowering after cataract surgery is not a long-term effect in glaucoma patients on medications. (Again, this is anecdotal; there is no solid clinical data to confirm my experience.)

Assuming a pressure drop does occur in a glaucoma patient following cataract surgery, what kind of pressure drop should you expect? In addition to the finding that a larger preop pressure correlates with a larger drop in pressure, the retrospective studies found that any drop that occurs will likely be much smaller in a patient who is on a lot of glaucoma medications than in a patient who’s on a single medicine.

Consider a Drug Holiday

Of course, a glaucoma patient could simply be returned to his preoperative medication regimen after cataract surgery. However, if the surgery does produce a decrease in IOP, it may be possible to reduce the patient’s medication load postop.

If a patient is an ocular hypertensive, I’ll often give him a drug holiday to see how much the pressure is lowered by the cataract surgery. I’m less inclined to try this in a patient with known glaucoma, although if the patient has relatively mild disease, I will sometimes do a drug holiday after simple cataract surgery based on what her pressure is shortly after surgery. I see this as an acceptable risk because taking out a cataract using a clear cornea approach doesn’t paint you into any corners in terms of later options. It doesn’t eliminate the possibility of performing subsequent glaucoma surgery, if needed.

If the patient’s pressure is in a reasonably safe range after cataract surgery, I’ll keep her off medications until she’s done with the steroids so I can get a sense of where the pressure is going to settle, then I’ll reintroduce medications as needed. How quickly I restart medications depends on the severity of the disease; in some cases the patient may go back on drugs relatively quickly. Generally, pressure spikes and other concerns are relatively manageable in the early postoperative period in this type of patient.

If a patient is on multiple glaucoma medications before cataract surgery, my decision regarding whether or not to give the patient a drug holiday would be based on the indication for the multiple medications. If the indication was advanced disease, that’s probably a patient who should have a combined procedure rather than cataract surgery alone. If the patient is on three or four medications because he started at a really high pressure but he still has relatively mild damage, it may be reasonable to do cataract surgery alone, although it’s unlikely that the patient will end up off of all of his medications. Whether I’ll consider a drug holiday in that situation depends on how the patient looks right after surgery.

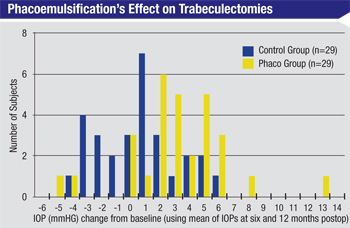

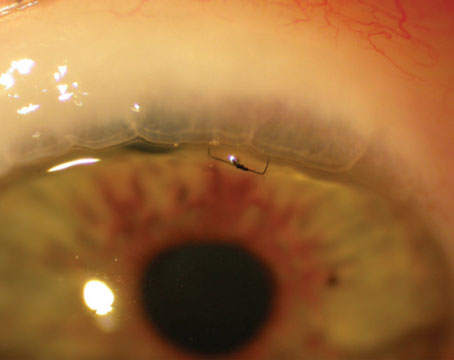

Trabeculectomy or Tube Shunt

A cataract surgery patient who already has a trabeculectomy or a tube shunt in place raises totally different concerns. If someone has a functioning trabeculectomy and you perform phacoemulsification, one of the biggest risks is that you’re going to cause the trabeculectomy to fail because of inflammation, scarring or related problems. Although clear cornea cataract surgery doesn’t directly alter the bleb (unlike earlier forms of cataract surgery) one study found that IOP rose about 3 mmHg in patients with functioning trabeculectomies after uncomplicated phacoemulsification.6 (See chart, above.) Clearly the surgery does impact the efficacy of the bleb, even if it doesn’t destroy it.

|

Unfortunately, there are only a few retrospective studies that have considered this issue, so there’s not much solid data to back up my conclusion. The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s newly launched IRIS Registry should eventually provide the kind of national, large-scale data that could help us answer this question.

When performing phacoemulsification on a glaucoma patient with a tube or trabeculectomy, the following strategies can help ensure a good outcome:

• If a patient has had prior glaucoma surgery, include the risks of failure in the consent discussion. When I see a patient in need of cataract surgery who has had prior glaucoma surgery, I explicitly include in my consent discussion—and document in the chart—that one of the biggest risks of doing cataract surgery in this situation is that the previous glaucoma surgery will fail and we’ll have to go back and do more glaucoma surgery.

• Schedule the surgery based on the patient’s visual needs and logistical considerations. If a patient has a trabeculectomy or a tube, I’d base the timing of cataract surgery primarily on two things: the patient’s visual needs, and the logistics of how the surgery will impact the patient’s life. In terms of the patient’s visual needs, the fellow eye becomes part of the discussion. Is it a priority to have visual rehabilitation as quickly as possible? Or does the patient have a fellow eye that he can get along with just fine?

In terms of logistics, you have to consider what the patient wants and what he can manage. I’d explain to the patient that he may need a lot more follow-up than that needed by a routine cataract surgery patient. In my practice a significant number of patients live two or three hours away, so the more involved follow-up may entail some significant logistic challenges for the patient and/or the patient’s family. In that situation I may time the surgery based on when it’s practical for the family.

• Keep a close eye on a patient with a trabeculectomy after cataract surgery. If your cataract patient has a functioning trabeculectomy, you don’t want to follow a standard postop routine in which you see the patient one day after surgery, a week to 10 days after that, and then a month later. Suppose you see the patient at one week and there’s a lot of inflammation. When there’s inflammation and the conjunctiva around the bleb is injected during the first week or two, if you fail to intervene with increased steroids or 5-fluorouracil injections or other maneuvers to prevent scarring you will have lost your opportunity to intervene and save the trabeculectomy. The postoperative care of such patients should not be delegated to others.

Checklist for Success

I find it helpful to use the following preoperative checklist when making a decision about how to proceed with a glaucoma patient who needs cataract surgery:

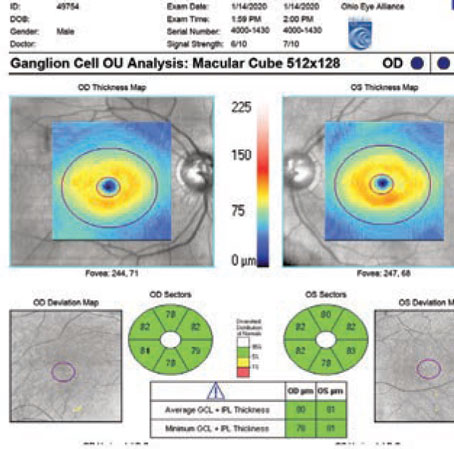

• Stage the glaucoma in both eyes. Before proceeding with the cataract surgery, you need to know how bad the glaucoma is. Knowing the pressure is not sufficient; you need to evaluate the optic nerve and visual fields.

• Perform gonioscopy. It’s important to determine the condition of the angle prior to cataract surgery. Perhaps gonioscopy has never been done on a patient; sometimes it was done years ago, and you need to reevaluate the condition of the angle.

Some literature suggests that the patient who has a narrow angle before cataract surgery is more likely to experience a drop in IOP after cataract surgery as a result of the opening of the angle; but if the patient has lots of peripheral anterior synechiae, you may be dealing with chronic angle closure that wasn’t previously recognized. The presence of PAS might indicate that the pressure will not decrease following the cataract surgery, and you might need to perform goniosynechialysis or another type of procedure to deal with the angle closure.

|

It seems reasonable to consider using phaco alone as a means to reduce IOP in some glaucoma patients with mild disease; it may delay or avoid the need for a future trabeculectomy.

|

• Review the medications. Not every patient who is on one medication is the same. A patient may have significant disease but be on only one medication because he’s allergic or intolerant to the others. You want to know that ahead of time, so if the patient has a pressure spike you’ll know what options you have for treating him. (In most situations like this you’ll want to consider combining a glaucoma surgery with the cataract surgery.)

• Review patient-related factors. As noted earlier, factors such as how easy it is for the patient to come in for follow-up and the condition of the fellow eye must be considered when you decide how and when to proceed with the cataract surgery.

• Talk to the patient. Make sure everyone is on the same page in terms of expectations. Given the very high expectations for cataract surgery vision outcomes that people have today, it’s always best to under-promise and over-deliver. (Note that visual recovery is known to be slower after a glaucoma patient undergoes combined surgery, although the final outcomes are similar to those with cataract surgery alone.) A glaucoma patient needs to understand that because of the disease he won’t be playing tennis and seeing 20/20 the day after surgery; he should not expect to have the same fabulous result that his neighbor may have had. And, make sure you document this conversation in the chart.

Proceed With Caution

Given the relative safety of today’s phaco-based clear cornea cataract surgery and its lack of impact on future glaucoma surgery options, it seems reasonable to consider using phaco alone as a means to reduce IOP in some glaucoma patients with mild disease; it may delay or avoid the need for a future trabeculectomy. Of course, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery can also be combined with cataract surgery in patients with mild disease.

A few other things to keep in mind in this situation:

• Keep the surgery simple. If you’re doing cataract surgery on a patient currently being treated for glaucoma, do the simplest and cleanest surgery you can, doing everything possible to avoid stirring up inflammation. I would use more steroids with this type of patient, rather than less.

• Don’t remove an asymptomatic cataract in a glaucoma patient just to reduce pressure. Some surgeons might consider removing an early, asymptomatic cataract as a way of lowering pressure. However, this option is probably unwise when an individual is being treated for glaucoma. I believe you should only take out a cataract based on a glaucoma patient’s visual needs, for two reasons: First, the IOP-lowering effect is not that predictable on an individual basis. Second, cataract surgery is not without risk; you can have complications. I certainly don’t think that cataract surgery as an IOP-lowering procedure (in the absence of vision-based indications) is the standard of care.

• Be prepared in case IOP increases instead of decreasing. The predictability of a pressure decrease in an individual patient is relatively poor. A recently published study by Mark A. Slabaugh, MD, and colleagues at the University of Washington in Seattle found that out of 157 open-angle glaucoma patient eyes undergoing cataract surgery, 60 eyes needed additional medications or laser treatment to control IOP during the first year postoperatively, or were found to have a higher IOP one year after surgery on the unchanged preoperative medication regimen.5 (In the latter group, higher preoperative IOP [p<0.001], older age [p=0.006], and deeper anterior chamber depth [p=0.015] were associated with lower postoperative pressure.) Enough patients will have an unexpected rise in pressure that you need to have a game plan ahead of time for dealing with such a possibility. It’s a good reminder that cataract surgery is not totally benign, especially when dealing with a glaucoma patient.

The main thing to remember is that a cataract patient who also has glaucoma should not be treated like a simple cataract patient. It’s easy to get burned if you don’t take stock of the patient’s disease, both in terms of what might need to be done during and after the cataract surgery, and in terms of how cataract surgery will influence the subsequent management of the glaucoma. If you evaluate the patient’s disease carefully, set appropriate expectations, do meticulous surgery and follow-up diligently, your glaucoma patient should end up with good vision, and you should end up with a happy patient.

REVIEW

Dr. Brandt is director of the glaucoma service and a professor in the department of ophthalmology at the University of California Davis School of Medicine; he is also a principal investigator in the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study.

1. Shingleton BJ, Gamell LS, et al. Long-term changes in intraocular pressure after clear corneal phacoemulsification: Normal patients versus glaucoma suspect and glaucoma patients. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:7:885-90.

2. Tong JT, Miller KM. Intraocular pressure change after sutureless phacoemulsification and foldable posterior chamber lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998;24:2:256-62.

3. Poley BJ, Lindstrom RL, Samuelson TW. Long-term effects of phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in normotensive and ocular hypertensive eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:5:735-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.12.045.

4. Mansberger SL, Gordon MO, Jampel H, Bhorade A, Brandt JD, Wilson B, Kass MA; Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. Reduction in intraocular pressure after cataract extraction: The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Ophthalmology 2012;119:9:1826-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.050. Epub 2012 May 16.

5. Slabaugh MA, Bojikian KD, Moore DB, Chen PP. The effect of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in medically controlled open-angle glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:1:26-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.08.023. Epub 2013 Oct 30.

6. Swamynathan K1, Capistrano AP, Cantor LB, WuDunn D. Effect of temporal corneal phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in eyes with prior trabeculectomy with an antimetabolite. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:4:674-8.