In this, the final part of our series on facial nerve palsy, we focus on the medical and surgical management of FNP. The treatment for facial nerve paralysis is a multimodal approach and planning depends on the patient’s age, as well as the etiology, severity, timing and duration of the facial paralysis. These factors must be considered to be sure they align with the patient’s goals and outcomes. (Click here to read Part 1 of this series on FNP.)

Medical Management

Medical management of FNP involves several considerations:

• Treat the underlying cause. Your approach to medical management depends on whether the cause is idiopathic or infectious.

• Idiopathic (Bell's palsy). Corticosteroids within 72 hours of onset have been included in the evidence-based treatment guidelines for Bell’s palsy recommended by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.1 Clinical guidelines recommend a 10-day course of oral steroids with five days at a high dose (prednisolone 50 mg/day for 10 days or prednisone 60 mg/day for five days) followed by a five-day taper.2 The benefit of antivirals as monotherapy or in combination with steroids is still debated. Some experts prescribe valacyclovir 500 mg by mouth twice a day for seven days along with corticosteroids.1

• Infectious. Infectious etiologies break down to either Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome (RHS) or Lyme disease. Similar to Bell’s palsy, RHS should be treated with corticosteroids to decrease vertigo and postherpetic neuralgia.1 These patients should also be treated with an oral antiviral to improve recovery and decrease complications.3

For Lyme-associated FNP, the typical treatment is a three-week course of oral doxycycline. Unlike Bell’s palsy and RHS, corticosteroid treatment in Lyme disease results in worse outcomes.1

• Manage the ocular surface. In the acute phase of FNP, ophthalmologists play a pivotal role in preventing irreversible blindness from corneal exposure.4 This is particularly important when ocular signs or symptoms of exposure keratopathy are present. The clinician must also evaluate corneal sensation. Patients with corneal hypesthesia in combination with corneal exposure are at extremely high risk for corneal ulceration and perforation. Artificial tears and thicker gel or ointment-based lubricants are the mainstay of therapy. If frequent dosing is needed, switch to preservative-free formulations to reduce allergic or toxic reactions. You can also use lipid-enhanced artificial tears. Some clinicians may consider autologous serum tears; however, these can be very expensive for patients.

|

|

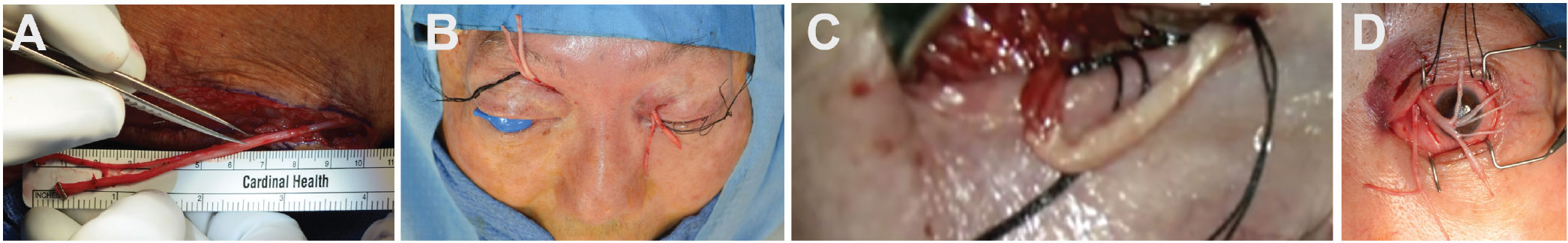

Neurotization steps: (A) Harvesting of sural nerves for grafting; (B) tunneling of sural nerve graft; (C) end-to-end coaptation of SON to sural nerve graft; (D) external photographs of dual sural nerve grafts split into fascicles for corneal grafting. Image credit: Charlson ES, Pepper JP, Kossler AL. Corneal neurotization via dual nerve autografting. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2022;38:1:e17-e19. Used with permission. |

As the normal blink function is impaired, the normal tear film physiology is dysregulated. Therefore, it’s best to take measures to improve the tear film quality. These include the usual eyelid hygiene measures such as warm compresses and eyelid scrubs for meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis. Oral medications may include omega-3 supplementation (fish and flaxseed oil), doxycycline or azithromycin. A recent study reported equivalency of effects of azithromycin as compared with doxycycline.5 Routine eyelid procedures such as thermal pulsation techniques (Lipiflow) may alleviate symptoms of MGD,6 however, these aren’t typically covered by insurance.

Moisture retention methods such as manually taping the eyelids shut, eye masks and humidification goggles/moisture chambers may also provide relief. Patients may consider optimizing their home environment by using humidifiers and turning off oscillating fans. Obstruction of tear outflow with punctal plugs or thermal punctal cautery helps tear retention in aqueous deficient dry eye. Bandage contact lens placement may also be considered; however, this will require antibiotic prophylaxis and patient compliance for regular follow-ups. Scleral contact lenses may be beneficial for patients who require long-term solutions but can be cost-prohibitive as they are not covered by insurance.

Chemical Denervation

Botulinum toxin use has gained popularity in the management of facial nerve paralysis. This neuromodulator may be used to temporarily relax muscles, thereby improving facial symmetry and function. Protective ptosis can be induced with 5 units/0.1 ml of botulinum toxin directly injected into the levator muscle.7 The most common adverse effect is diplopia, which can last up to three months and presents as a vertical misalignment that clinically behaves as a superior rectus palsy.7 The majority of these will resolve with observation. Botulinum toxin can additionally be used to address symptoms of aberrant facial nerve innervation including hypertonicity of the affected side, synkinesis of facial muscles along with neuromuscular retraining therapy, and gustatory lacrimation (“crocodile tears”).8,9

Surgical Management

Once the cornea is adequately protected and recovery deemed unlikely, longer-term planning for eyelid and facial reanimation may take place in an individualized manner.4 The specific surgical approach depends on factors such as the etiology and density of facial paralysis, the patient's overall health and the surgeon's expertise.

• Occlusive techniques. Should patient symptoms persist despite conservative measures, or if there are suspected long-term sequelae of their facial nerve palsy, surgical procedures should be considered concurrently with ocular surface lubrication. Less invasive surgical treatments that may be performed in the clinical setting are temporary tarsorrhaphy or a small permanent tarsorrhaphy. These are the simplest and most common procedures that are also used in conjunction with a variety of oculoplastic procedures. These can also be used as temporizing measures as a bridge for a patient who may not yet be medically optimized for the operating room to undergo general anesthesia. The useful occlusive techniques are the following:

• Temporary suture tarsorrhaphy to fully close the eyelids. This is commonly used for patients unable to fully blink, with a poor protective Bell’s reflex, and/or with severe lagophthalmos. One must consider the visual status, as these will occlude the visual axis. This approach has also been used longer term for severe neurotrophic ulcers to assist with healing.

• Lateral permanent tarsorrhaphy is a quick procedure that can be done in the office setting and is the most common form of permanent eyelid closure. However, closing the temporal palpebral fissure can limit peripheral vision, contribute to mechanical ptosis of the upper eyelid, and not be aesthetically pleasing to the patient.

• Medial permanent tarsorrhaphies are less commonly performed but can improve the medial descent of the lower eyelid when there’s poor orbicularis tone. These will usually require closure of the puncta simultaneously and can also be helpful for aqueous deficient dry-eye patients (permanent puncta occlusion).

Less common measures include botulinum toxin (as detailed in the previous section), hyaluronic acid gel (fillers) and external temporary eyelid weights. The upper eyelid can be mechanically weighed down with hyaluronic acid gel fillers. This is reversible with hyaluronidase. External temporary eyelid weights typically have an adhesive backing that can be applied to the skin of the upper eyelid to assist with immediate closure, however long-term uses of adhesive can cause skin breakdown of the delicate eyelid skin. Although these procedures are less commonly seen, they may provide temporizing measures or may be ideal for the patient who isn’t medically stable enough for the operating room.

• Static techniques. Static techniques improve the resting symmetry of the face without restoration of movement. FNP is associated with multiple periocular sequelae affecting the dynamic function and static appearance of the eyelids, including lagophthalmos, brow ptosis, upper and lower eyelid retraction, lower eyelid ectropion and secondary skin contracture.1 Multiple procedures are often required to restore eyelid function and symmetry and protect the ocular surface.10 Although these are static procedures, restoring the normal anatomical repositioning of the eyelids can augment the natural blink reflex. A few of the most common procedures used to address the specific challenges associated with FNP include:

• Gold weight implantation. This involves placing a gold or platinum weight within the upper eyelid to assist with complete eyelid closure. The weight counteracts the weakness or paralysis of the orbicularis muscle responsible for eyelid closure and protection of the cornea.

• Brow lifts. A variety of brow lift techniques may be employed to assist with eyelid lifting surgeries. A recent case series described a “switch technique” that uses full-thickness skin grafts from direct brow lift surgery to repair the skin contracture and paralytic lower eyelid ectropion, addressing multiple sequelae into one surgery.10

• Ectropion repair. Paralytic lower eyelid ectropion repair involves repositioning the suspension tissues of the lower eyelid to provide support and improve the natural blink function. This addresses the lower eyelid skin laxity and loss of orbicularis tone seen in FNP.

• Cheek/midface lift. In conjunction with lower eyelid ectropion repair, the surgeon must recognize that paralysis of the malar-cheek soft tissues in addition to orbicularis paralysis contributes to the lack of support of the lower eyelid. The paralysis results in the weakening of medial and lateral canthal ligaments and orbitomalar ligaments. When evaluating these patients for reconstruction, the surgeon should consider a simultaneous midface lift. This may include suborbicularis oculi fat repositioning (SOOF lift), lateral orbicularis orbital suspension, and lateral canthopexy and/or canthoplasty with fixation sutures at the lateral orbital rim. These techniques have been shown to be effective in static lower eyelid malposition surgery.

• Corneal neurotization. When neurotrophic keratitis is present, corneal neurotization reinstates corneal sensation through the induction of donor nerve tissue. The donor nerve (most commonly the inferior orbital nerve) is placed subconjunctivally near the corneal limbus. A single case report described the use of a dual nerve grafting approach via simultaneous parallel sural nerve grafts from both the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves to the affected contralateral cornea with return of sensation by postoperative week 11.11

• Dynamic techniques. Facial reanimation surgery, also known as facial nerve reconstruction, is aimed at restoring symmetry of the face with restoration of facial movement. The procedure involves the repair, redirection or replacement of the damaged facial nerve or its branches to reestablish innervation to the facial muscles. Depending on the specific needs of the patient, techniques include:

— Nerve grafting. Here, a healthy nerve from another part of the body (typically the sural nerve from the leg) is harvested and used to bridge the gap of the damaged facial nerve.

— Nerve transfer. Contralateral facial nerve grafts are also performed where the contralateral (unaffected) facial nerve is bridged to the damaged facial nerve.

— Muscle transfer. This involves transferring an adjacent functioning muscle (usually the temporalis muscle) from its original insertion to replace the paralyzed muscles and is connected to the remaining facial nerve or nerve graft to restore movement.

— Free muscle transfer. A donor muscle from another part of the body (typically the gracilis muscle in the thigh) is harvested along with its blood supply and transferred to the face.

— Microneurovascular free flap. This approach uses microsurgical techniques to carefully dissect and reconnect blood vessels and nerves during the flap transfer, ensuring blood supply and innervation to the newly transplanted tissue.

The goal of facial reanimation surgery is to restore facial symmetry, improve facial movement, and enhance the patient’s ability to communicate, express emotions and perform daily activities. Post-surgery, patients may require rehabilitation, including physical therapy and exercises, to optimize facial function and achieve the best possible outcomes.

Special Cases

Facial nerve palsy can also occur due to special circumstances, or in unique patient populations.

• Trauma/iatrogenic. Because the facial nerve courses through the rigid bony structures of the temporal bone, craniofacial trauma commonly causes FNP either through direct damage from bony fragments or ischemia nerve compression from expansile edema. High-resolution computed tomography is used for the localization of nerve injury in suspected cases of temporal bone trauma. In the absence of gross radiographic abnormalities, electrophysiologic testing helps predict the likelihood of spontaneous recovery. In patients with deteriorating facial nerve injuries by electroneuronography, surgical exploration is the preferred management.12 The accepted recommendation for surgical management is indicated for patients with immediate-onset and complete paralysis. Patients who, due to their severe general condition, can’t undergo early facial nerve decompression may benefit from delayed treatment for up to three months after the injury.13

• Congenital. There are special considerations in the pediatric population. Although children as young as 2 years old have successfully undergone free tissue transfer for smile restoration,14 waiting until at least 5 or 6 years of age, around the time the child is school-aged and becomes self-aware, is preferred. Delaying major procedures until this age provides time for the growth of nerves and vessels, whose small caliber may lead to free flap failure, and allows children to be mature enough to understand and participate in their own care.14

Postoperative Care

Postoperative healing in FNP patients can be prolonged due to the impaired venous and lymphatic drainage system. Lymphatics play a crucial role in the body's healing process by removing excess fluid, debris and immune cells from the surgical site. In facial paralysis, the physiologic action of the musculoskeletal pump is impaired. There’s a lack of rhythmic contraction and relaxation of facial muscles and therefore slowing of venous and lymphatic drainage. Some considerations for postoperative healing in patients with facial paralysis include the following:

• Elevate the surgical site above the heart. Sleep with the head elevated and avoid sleeping on the surgical side as edema will accumulate with gravity.

• Proper wound care involves keeping the surgical site clean, dry and protected from infection. Cool compresses in the immediate postoperative period have also been shown to decrease bruising. Close monitoring of the wound is essential to detect any signs of infection or delayed healing.

• Manual lymphatic massage using gentle pressure creates rhythmic movements that help to mobilize fluid and promote drainage. This may also improve circulation, promote wound healing and reduce swelling. In one study, manual lymphatic drainage has been effective in reducing facial measurements in orthognathic surgery postoperatively. However, when considering the patient’s pain and swelling perception, the researchers found no difference.15

• Close follow-up and monitoring: Patients with poor lymphatics require close monitoring during the postoperative period. Regular follow-up appointments with the surgical team are necessary to assess wound healing, manage complications and adjust the treatment plan as needed.

Edema is part of the normal healing process after surgery. However, in patients with poor facial muscle function, swelling can be more significant and persistent. The surgeon should set these expectations for the patient and provide education. This can be a challenging period for our patients and requires reassurance and emotional support throughout the postoperative course.

Complications

Prolonged or poorly managed exposure keratopathy can be detrimental, especially in the setting of poor corneal sensation. Concomitant corneal hypesthesia and exposure put the eye at high risk for corneal ulceration, corneal melt with perforation and blindness, which may precede evisceration or enucleation. Facial muscle wasting over time can lead to significant facial asymmetry that may be difficult to manage. The postoperative course after reconstructive surgeries can be prolonged with pronounced periorbital and facial edema. This is mainly due to impaired venous static pumps of the facial lymphatics from lack of muscular impact.

Prognosis

Recovery from facial paralysis varies and depends on the etiology and severity of paralysis at presentation. Patients with idiopathic Bell’s palsy typically begin to recover at three weeks and continue to recover for six months. These patients typically don’t require surgical management. However, patients with Ramsay-Hunt syndrome carry a poorer prognosis. Although self-limiting, complete recovery occurs in only half of cases.1 Among patients who present with dense, flaccid paralysis, approximately 61 percent recover with full function.

In contrast, patients who present with facial weakness, but not complete paralysis, recover full function in 94 percent of cases.1 The most devastating facial nerve paralysis cases are in those instances after trauma or tumor, where the facial nerve must be sacrificed during surgical resection. This results in permanent and complete facial paralysis; these cases should be considered for permanent surgical interventions, including static or dynamic facial nerve reanimation.

In conclusion, the medical and surgical management of FNP is highly individualized, and the specific treatment plan will depend on the underlying cause, severity of symptoms and the patient’s overall health. A more general way to approach facial nerve palsy is based on suspected time for improvement for return of facial nerve function and severity of symptoms. Time periods can be generalized by:

• “Soon” (weeks to months). This necessitates supportive management with tears, ointment, taping eyelid shut, etc.

• “Later” (six months to a year). Depending on the severity of problems (corneal exposure, concomitant corneal hypesthesia with risk for ulceration, functional status, and patient comorbidities), start with conservative measures and after the observation period, you may consider proceeding with surgical management (gold weight, ectropion repair, etc.). These patients may later be considered candidates for facial reanimation.

• “Never” (i.e., transected facial nerve). These are the typical facial reanimation patients; however, as nerve regeneration will take one to two years; it’s prudent to provide further support with static eyelid and/or facial reconstruction.

While medical and surgical interventions can be promptly initiated, extensive eyelid and facial reconstruction should involve consultation with a skilled oculoplastic or facial plastic surgeon who specializes in facial nerve palsy to determine the most appropriate surgical approach for each patient.

1. MacIntosh PW, Fay AM. Update on the ophthalmic management of facial paralysis. Surv Ophthalmol 2019;64:1:79-89.

2. Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, Schwartz SR, Drumheller CM, Burkholder R, Deckard NA, Dawson C, Driscoll C, Gillespie MB, Gurgel RK, Halperin J, Khalid AN, Kumar KA, Micco A, Munsell D, Rosenbaum S, Vaughan W. Clinical practice guideline: Bell's palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;149(3 Suppl):S1-27.

3. Monsanto RD, Bittencourt AG, Bobato Neto NJ, Beilke SC, Lorenzetti FT, Salomone R. Treatment and prognosis of facial palsy in Ramsay Hunt Syndrome: Results based on a review of the literature. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016;20:4:394-400.

4. Rahman I, Sadiq SA. Ophthalmic management of facial nerve palsy: A review. Surv Ophthalmol 2007;52:2:121-44.

5. Upaphong P, Tangmonkongvoragul C, Phinyo P. Pulsed oral azithromycin vs 6-week oral doxycycline for moderate to severe meibomian gland dysfunction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2023;141:5:423-429.

6. Hu J, Zhu S, Liu X. Efficacy and safety of a vectored thermal pulsation system (Lipiflow) in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2022;260:1:25-39.

7. Ellis MF, Daniell M. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) when used to produce a protective ptosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001;29:6:394-9.

8. Jeong J, Lee JM, Kim J. Neuromuscular retraining therapy combined with preceding botulinum toxin A injection for chronic facial paralysis. Acta Otolaryngol 2023;143:5:446-451.

9. Jeffers J, Lucarelli K, Akella S, Setabutr P, Wojno TH, Aakalu V. Lacrimal gland botulinum toxin injection for epiphora management. Orbit 2022;41:2:150-161.

10. Nagendran ST, Butler D, Malhotra R. Direct brow lift and skin contraction in facial nerve palsy: A switch technique. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2021;37:(3 Suppl):S130-S131.

11. Charlson ES, Pepper JP, Kossler AL. Corneal neurotization via dual nerve autografting. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2022;38:1:17-19.

12. Davis RE, Telischi FF. Traumatic facial nerve injuries: Review of diagnosis and treatment. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 1995;1:3:30-41.

13. Marszał J, Bartochowska A, Gawęcki W, Wierzbicka M. Efficacy of surgical treatment in patients with post-traumatic facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Pol 2021;75:4:1-6.

14. Banks CA, Hadlock TA. Pediatric facial nerve rehabilitation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2014;22:4:487.

15. Yaedú RYF, Mello MAB, Tucunduva RA, da Silveira JSZ, Takahashi MPMS, Valente ACB. Postoperative orthognathic surgery edema assessment with and without manual lymphatic drainage. J Craniofac Surg 2017;28:7:1816-1820.

16. Fay AM, Dolman PJ. Diseases and disorders of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Section 7: Neurologic disorders. In: Management of Facial Nerve Palsy. New York: Elsevier, 2016:593-600.