The goal of minimally-invasive glaucoma surgery is a noble one: Offer patients with mild or moderate glaucoma an option that can treat their disease without exposing them to the risks associated with more invasive procedures. However, even the best-laid plans can go awry, and you sometimes have to manage MIGS complications.

In this article, surgeons detail what complications could arise during MIGS procedures and offer advice on how to manage them. We’ll start by discussing general complications that can occur across many of the MIGS procedures, regardless of which outflow or inflow source the doctor is tackling. Then we’ll discuss the specific procedures, what each accomplishes, their most common complications and how to manage them.

General MIGS Complications

While MIGS is an effective way to manage glaucoma in some patients, there are complications associated with each procedure. However, as Robert Noecker, MD, MBA, the director of glaucoma at Ophthalmic Consultants of Connecticut says, “MIGS procedures aren’t problem-free, but they have fewer problems than standard procedures, and these problems are quite manageable. You just have to be aware of the potential issues. If you address them during the procedure or immediately after, then you should be successful.”

Common issues associated with MIGS include challenges using a gonioscope, locating the trabecular meshwork, and preventing and managing excess blood reflux.

Since many procedures require the use of a goniolens, Reay Brown, MD, a glaucoma specialist practicing at Atlanta Ophthalmology Associates, says, “Perhaps the most important thing is to absolutely insist that you achieve a good view before you perform one of these procedures.” Dr. Noecker says manipulating a goniolens can be one of the toughest aspects of an angle procedure. “Using the goniolens with your non-dominant hand with the tool in your dominant hand takes getting used to,” he adds. He urges users not to apply too much pressure on the cornea when using the gonioscope, explaining, “Wrinkling is possible, which will further obstruct your view of the angle.”

Dr. Brown remarks that the goniolens is not ideal, and says he’s working to achieve a better and wider view. To accomplish this, Dr. Brown uses a disposable goniolens that’s like a contact lens. “You don’t have to hold it in place, which is very helpful,” Dr. Brown says. While he acknowledges gonioscopy technology’s need to improve, he is adamant that it can and will improve.

Locating the trabecular meshwork is another crucial step in performing many MIGS procedures. “It’s very important to learn the anatomy, as all of these procedures require you to place something in a particular location,” says Brian Flowers, MD, a glaucoma specialist and managing partner of Ophthalmology Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “You can practice viewing the angle in your office by doing a lot of gonioscopy,” he says. Dr. Brown suggests staining the meshwork with Vision Blue, saying that he’s found that to be a big help.

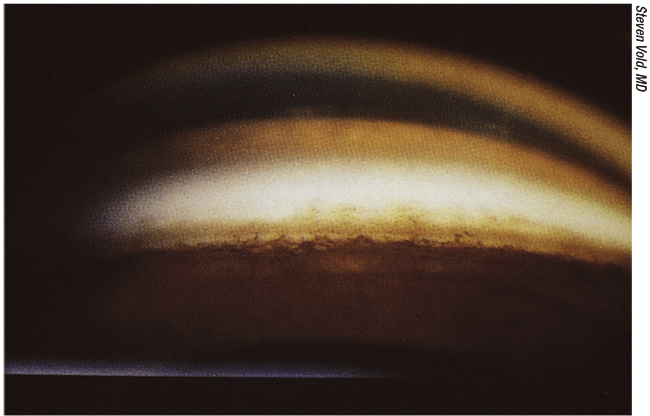

|

| Figure 1. Locating the trabecular meshwork is a crucial step in many MIGS procedures. Fort Worth, Texas’ Brian Flowers, MD, says learning the anatomy of the angle is important since many MIGS procedures require you to place something in a particular location. |

Another potential issue to be aware of is blood reflux. Since the main goal of MIGS is to lower IOP, this makes it easier for blood to reflux back into the canal, Dr. Noecker points out. While experiencing some blood reflux can serve as a confirmation that you’re in the right area, Dr. Noecker adds, “It’s like tapping oil, it’s a good thing…however it can become excessive.” In order to prevent or reduce blood reflux, Dr. Noecker says that viscoelastic is helpful. “I like to keep the pressure a little bit on the high side to push back on the blood. Doing this makes it harder for the blood to enter the eye. That usually works quite well. You may have some blood cells floating around, but not a frank hyphema, which would obscure the vision a lot.”

Another more intuitive way to limit blood flow is to minimize trauma to the iris or ciliary body, which can bleed more readily than an area like the trabecular meshwork. “When you do these canal-based procedures you should get a little blood,” says Dr. Noecker. “But if you’re getting a lot of blood, you may have traumatized the ciliary body or the iris.” To combat this, he suggests inflating the entry chamber very wide. “This can help to push the vascular tissues away. Also, keeping the pressure a little on the higher side is helpful in getting a good view and confirming that you’re entering the canal and not getting posterior, where the ciliary body is.”

Trabecular Outflow Techniques

Moving on to techniques that increase trabecular outflow, these MIGS procedures deal with removing or bypassing part of the trabecular meshwork or Schlemm’s canal in order to increase flow through the conventional outflow path.

• iStent and Hydrus. Glaukos’ iStent and iStent Inject can be inserted into Schlemm’s canal, effectively bypassing the trabecular meshwork and creating a path for aqueous humor to move from the anterior chamber into the canal to restore natural outflow. Similarly, Ivantis’ Hydrus can be inserted into Schlemm’s canal; it aims to open the channel so blocked fluid can flow more freely. The two procedures have similar challenges: implanting the device fully and managing hyphemas.

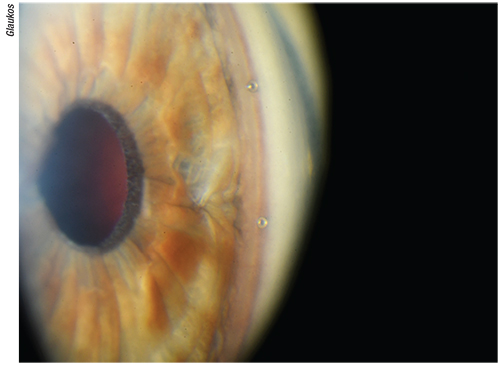

|

| Figure 2. Surgeons say rotating the patient’s head can position the trabecular meshwork into an almost verticle position which creates an easy, flat target for the iStent or iStent Inject, helping the surgeon properly insert it into Schlemm’s canal. |

For both the iStent and the Hydrus, it’s possible to inject the device into the wrong location, such as the sclera or the posterior wall. “The issue is making sure it’s placed in the right location,” says Dr. Flowers referring to the Hydrus. However, Dr. Brown notes, “You can tell when it’s stuck because you can’t move it along the canal.”

“In the case of a superficial implantation, the iStent doesn’t sit properly and the rings are too visible.” Dr. Brown continues, “The fix is to simply pull back, flatten the approach and then it will slide freely along the canal.” Rotating the head farther can help to position the meshwork into an almost vertical position, creating an easy, flat target, surgeons say. “It’s an intraoperative issue; you simply adjust your positioning,” Dr. Flowers says.

When it comes to managing a hyphema or a microhyphema, it’s important to remember that, because you’re performing a pressure-lowering procedure, blood will flow more readily and you should expect to have to deal with at least some blood reflux, remarks Dr. Noecker. “Rinse out the blood that refluxes when you tap in but at the same time, prevent it from accumulating overnight,” he says. Blood reflux can be common in these procedures, which is why understanding how to manage it is crucial. “You just keep washing it out and eventually it stops,” says Dr. Brown. “I haven’t had a problem with blood postop.”

Another issue to be aware of is reimbursement. If an insurance company deems a patient’s glaucoma case too advanced, it may deny reimbursement for the iStent or iStent Inject and be more in favor of a procedure that more significantly lowers IOP. “Insurance companies are very strict about denying coverage for patients who have more serious disease,” Dr. Brown says. This is where it can be beneficial to know how to perform multiple MIGS procedures and interpret which will work best for a given patient, depending on the severity of her glaucoma versus how much IOP you are looking to lower, surgeons say.

• Trabectome. The Trabectome aims to improve outflow by using electrocautery to ablate a portion of the trabecular meshwork. Complications here sometimes arise as a result of difficulty in maneuvering the device, which might mean less angle access, issues with coordination and potential thermal injury.

“[The Trabectome] is somewhat cumbersome to use because it’s a little bit big,” says Dr. Noecker. “Since you rely on electrocautery and are therefore using a thermal effect, you have to have some fluid flowing to keep the temperature down. The worst-case scenario is you can burn something you don’t want to burn.” As far as avoiding that, Dr. Noecker says technique is important, “The main thing is to have a gentle touch with the goniolens,” he says. “You can get a wrinkly view, which makes it hard to keep the Trabectome just in that trabecular space. Don’t press down on the cornea to try to get all of the air out and get a good view. Pressing the cornea can deflate it. I put viscoelastic on the cornea so that the goniolens can kind of float on that and give you a good view.”

Surgeons say that they can only treat between 90 and 120 degrees using the Trabectome, which, again, makes it important to understand the patient, his specific glaucoma case and IOP-lowering needs. “[The Trabectome] is sometimes not enough to have an impact,” remarks Dr. Brown. “The makers of the Trabectome are trying to make a comeback with some newer designs which may have a role in the future.”

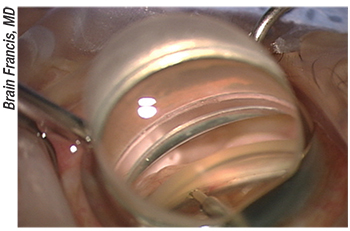

|

Figure 3. Ablation of the trabecular meshwork is seen through the white appearance of the outer wall of Schlemm’s canal to the right of the Trabectome tip. Dr. Noecker suggests using viscoelastic on the cornea to avoid wrinkling when using the goniolens. This can help provide a good view and aid in keeping the Trabectome in the trabecular space. |

• Kahook Dual Blade. This procedure completely removes a strip of the trabecular meshwork in order to increase outflow. “It’s kind of like [the Trabectome],” Dr. Noecker says, “but without the cautery part. It’s very straightforward and it’s a relatively inexpensive device, but you’re limited in how much of the trabecular meshwork you can open in one sitting.” It can involve complications that have already been discussed, such as problems using the gonioscope, accessing more than 120 degrees of the meshwork and dealing with blood reflux.

• Circumferential trabeculotomy procedures. This MIGS method lowers IOP by inserting a suture (GATT), or device (Trab360) into Schlemm’s canal, navigating 180 or 360 degrees around the canal, and then performing a trabeculotomy. Complications involve the suture or device getting stuck (which we’ll discuss in the next section), accidentally pulling it out of the canal and dealing with more blood reflux than usual as you remove the meshwork tissue.

Dr. Brown discusses what to do in the case of a device accidentally being pulled out. “Regarding the portion of the catheter that’s outside of the eye, it’s easy for that to get caught on something, or be pulled out. You have to know how to deal with that portion of the catheter,” he says. “In that event you just start over. As you get more experienced, that shouldn’t happen.”

When it comes to blood reflux, Dr. Flowers says, “Each time you do a trabeculotomy you’ll get bleeding. [To manage this], it’s always important when you pierce the eye that you keep it pressurized afterwards. If you have the eye full of viscoelastic, you have to leave it in there for a while to tamp on the blood. Once you rinse the viscoelastic out, immediately make sure that the balanced salt solution goes right in so that the pressure stays above 20 mmHg while the viscoelastic discourages bleeding right afterwards. It’s transient; blood usually goes away within a few days.”

Dr. Brown agrees, saying, “It’s usually managed just by waiting. I’ve never had to re-operate on a patient.”

ABiC Procedures

An ab interno canaloplasty procedure seeks to improve outflow by catheterizing the canal and dilating the natural outflow pathways, including Schlemm’s canal, the trabecular meshwork and the distal outflow system. Complications associated with an ABiC procedure include overinflation of Schlemm’s canal and the device getting stuck. “I think the main complication could be overinflation of Schlemm’s canal with the Healon,” notes Dr. Flowers. “When you’re doing ab interno there are two ways to do it; you can do it with Sight Sciences’ device (the OMNI) which determines for you how much viscoelastic is going to be injected, or you can do it with the Ellex probe (iTrack) where you control how much gets injected.” In regard to Ellex’s iTrack, Dr. Flowers continues, “When you’re doing ab interno, you don’t have to worry about a scleral window rupturing because you’ve injected too much viscoelastic, so you can inject a little more than you would in an ab externo procedure. It’s nice to be able to be a little bit more aggressive, but if you get carried away and overdo it with the injecting, you can create a Descemet’s detachment, which can be an issue.”

Dr. Flowers says that how you manage these complications depends on their location. “If you have a Descemet’s detachment and it’s superior, you can leave a little bit of air in the eye, which will tend to flatten it out,” he says. “Sometimes you can hit it, pop it with a YAG laser and the fluid will leak out. [However] I’ve never had a Descemet’s detachment that ultimately compromised the vision.”

When discussing the propensity for the device to get stuck, Dr. Flowers estimates it happens about 10 percent of the time; however he goes on to explain how to remedy this issue. “If you can’t advance it all the way around, you can do various maneuvers to try to advance it as far as possible,” he says. “A typical maneuver would be to pull back and then advance it again—a back-and-forth motion that breaks through the blockage.” Dr. Flowers offers additional management techniques: “You can put a little external pressure on the eye where the iTrack is,” he says. “You can pull it out one way then turn around and go the other direction. If that doesn’t work, you inject and treat the areas that you can. Think about a circle; if you get a quarter of the way around one way, then halfway around going the other way, at least you can inject those areas and treat three quarters of the eye.”

More specifically, with regard to the OMNI, Dr. Flowers says, “It’s really a combination of canaloplasty and GATT, so it has similar complications.” The OMNI device first catheterizes and viscodilates, then performs a trabeculotomy. In terms of bleeding, Dr. Brown says that since viscodilation is done first, that reduces the blood reflux, both at the time of surgery and postop. “There’s more direct control of what you’re doing in this procedure as it’s less likely for the catheter to get caught on something or to have the tech inadvertently pull it out,” he says. While issues may not be as pronounced as those with GATT or an ABiC procedure, Dr. Noecker says there are things to be aware of. “Don’t do the procedure until the view is great. Pressurize the eye as much as possible during the procedure, which can help enhance the view so that the cornea is not wrinkling and you have a nice clear view of the trabecular meshwork. This also keeps the other structures away from the trabecular meshwork so you don’t traumatize them inadvertently. And the most important thing to prevent bleeding is to make sure the pressure is on the higher side.”

| The Promise of MIGS |

| Many doctors choose to treat glaucoma using medication because trabeculotomies and tube shunts are seen as more aggressive approaches that carry inherent risks despite IOP-lowering efficacy. However, many patients don’t need a dramatic reduction in pressure. Wills Eye Hospital’s Marlene Moster, MD, presented an overview of minimally-invasive glaucoma surgery at the 2014 FDA Workshop in Washington, D.C., “Supporting Innovation for Safe and Effective MIGS.” She estimated that 75 to 80 percent of patients have the ability to control glaucoma symptoms using medication. By undergoing MIGS, patients can decrease their dependency on medication and therefore minimize risks associated with prolonged medicinal use, which include drug side effects, the medications’ financial burden and problems with adherence. MIGS aims to lower IOP by improving outflow or reducing inflow from an ab interno approach. This can be achieved through bypassing or eliminating the trabecular meshwork, shunting aqueous humor into the suprachordial or subconjunctival space or reducing aqueous humor production. MIGS differs from traditional procedures in patient head position, microscopic or gonioscopic view, as well as placement of the surgeon’s hands. There’s minimal trauma associated with MIGS because there’s less disruption to the normal anatomy of the eye, surgeons say. In most instances, this can lead to a quicker postop recovery, possibly allowing patients to resume day-to-day activities after only a short period of time. MIGS procedures can also be combined in order to achieve higher efficacy. Since there are various ways in which MIGS seeks to lower pressure, should an initial procedure fail or not achieve desired results, a doctor can try another MIGS method. This is why it’s suggested to know how to perform more than one procedure, preferably ones that seek to lower pressure through different paths. Brian Flowers, MD, a glaucoma specialist and managing partner of Ophthalmology Associates in Fort Worth, Texas, suggests learning how to do a Schlemm’s canal procedure and also learning to do some form of gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, or GATT. Learning procedures that lower IOP through different methods, he reasons, can allow you to analyze a patient and decide which MIGS would best suit her specific glaucoma case. While MIGS isn’t as efficient in lowering IOP as a traditional surgical approach, these procedures can provide modest reduction in pressure, and they continue to show increases in efficacy as MIGS methods and devices advance. MIGS can decrease and, in some cases, completely eliminate the risks associated with traditional surgery, which is why it continues to gain popularity. Reay Brown, MD, a glaucoma specialist practicing at Atlanta Ophthalmology Associates discusses the aims of the procedures. “The goal is to lower the pressure, that’s number one, and number two is to get patients off medication as much as possible,” he says. “That’s also very important and is a great benefit to the patient. Reducing the medication burden is a gain financially, but it also helps with side effects.” Robert Noecker, MD, MBA, the director of glaucoma at Ophthalmic Consultants of Connecticut, says, “It’s a whole new era with these procedures and they’re certainly, as a group, safer than traditional glaucoma surgery.” —A.S. |

Subconjunctival Outflow

Using this technique, IOP is lowered by bypassing the conventional outflow pathway altogether. Here, aqueous humor moves from the anterior chamber into the subconjunctival space, effectively creating a new drainage canal.

• Allergan’s XEN gel stent. Complications associated with inserting this device involve issues with patient facial anatomy, ensuring flow is established and monitoring the patient postop.

“The biggest challenge is the injector itself,” Dr. Brown acknowledges. “Especially in the left eye, it can be hard to work over a high cheekbone.” Similarly, Dr. Noecker notes, “It can be difficult depending on patient anatomy, as you ideally want to get the stent to inject between 11 and 1 o’clock superiorly underneath the eyelid.” In order to manage facial-anatomy complications, Dr. Noecker says, “You can use a second instrument to twist the eye in order to kind of move it away from the bad anatomy site. It takes a little practice, but you can rotate the eye a few clock hours, and then you have space to do the injection.”

For a successful procedure, flow from the anterior chamber into an internal bleb must be established. “You confirm this by increasing the pressure in the eye and washing the viscoelastic out,” Dr. Noecker says. “That’s an important step. Once the device is placed, you want to rinse the eye out and remove all the viscoelastic so that it doesn’t clog the tube. You want to establish that fluid is going through the tube and puffing up the conjunctiva to make a bleb. Then you can be confident in the function of the stent. If you don’t do that, the flow may not start and it’s easier for subconjunctival scarring to begin.”

Since this is a bleb procedure, albeit an ab interno one, there can be cases of leakage and scarring of the bleb in addition to exposure of the tube. For these reasons, Dr. Noecker says that you have to follow patients fairly closely postop. “You need to manage the bleb,” Dr. Brown adds. “It’s important to be able to needle these blebs, which is something not necessary with other internal procedures.” Dr. Noecker points out that, in terms of postop monitoring and intervention, “The good thing is that you can do something. The bad thing is that you have to do it.”

Aqueous Humor Reduction

Here, the ciliary body is treated in an effort to lessen the production of aqueous humor and, ultimately, lower IOP.

• Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation. Complications that can occur when performing an ECP procedure include inflammation and problems working with the probe.

Dr. Flowers says that the biggest complication to be aware of with ECP is inflammation. Dr. Noecker agrees, saying, “You tend to get more inflammation because you’re treating the ciliary body. [To manage this] the patient has to be on steroids a little bit more.” Dr. Flowers says intracameral steroids have been a great help. “We used to get fibrin—a protein buildup—in the eye after the surgery,” he says. “But years ago we started using intracameral steroids and it virtually eliminated fibrin. A very robust anti-inflammatory treatment will minimize inflammation complications.”

To avoid further inflammation, Dr. Noecker says, “You have to be careful with the endo probe in the eye so as not to traumatize the iris by either lasering or bumping the iris, because that will lead to a fair amount of inflammation.”

| “It’s a whole new era with these procedures and they’re certainly, as a group, safer than traditional glaucoma surgery.” — Robert Noecker, MD |

Dr. Flowers has some final tips. “Make sure that the lens [at the tip of the probe] is clean before it is autoclaved,” he says. “If you leave any debris on the lens of the camera then it’ll get baked on and mess up your view. The lens is very durable so you can wipe it with some force to make sure the tip is clean. Also, when you insert the camera into the eye, make sure you’re in a blood-free zone so you don’t get blood on the tip of it, which would obscure your view.”

The Future

MIGS is at the cutting edge of glaucoma surgery; and Dr. Flowers says, “MIGS is here to stay.” Dr. Brown calls it “the greatest breakthrough in glaucoma to come about in [my] 30 years within the industry. The goal now is to increase efficacy so that we’re able to lower pressure in patients who have more advanced disease and higher pressure.”

MIGS is still a relatively new category in glaucoma treatment and while each procedure has its complications, doctors continue to explore management practices as MIGS provides an alternative to medical therapy and more invasive surgery. “We appreciate having these procedures,” Dr. Noecker says. “They aren’t perfect, however, and anything we do involves a little bit of a risk or a downside. However, by knowing the downsides, we can make these surgeries safe and give people good vision quickly while, at the same time, addressing IOP.” REVIEW

Dr. Noecker reports financial ties to Glaukos, Ellex, Sight Sciences, BVI and Allergan. Dr. Brown is the chief medical officer for Sight Sciences. Dr. Flowers is a consultant for and does research with Glaukos, Ivantis, Alcon, iStar, InnFocus and Sight Sciences.