Retinal specialists are pleased with the progress they’ve made while treating neovascular age-related macular degeneration in recent years, using anti-VEGF injections to help keep half of diagnosed patients at 20/40 or better, according to one major retrospective study.1 Gone are the days of automatically using focal macular laser photocoagulation to seal leaking vessels in a primitive attempt to temporarily spare parts of the macula not yet ravaged by disease. But as physicians well know, reflecting on how far they’ve progressed does nothing to prepare them for how far they still must go.

The sad and challenging fact is that even with today’s revolutionary drugs quieting the maculas of so many sighted success stories, some patients struggle to maintain their vision, even when faithfully following their intravitreal injection schedules. In this report, retinal specialists discuss strategies you can use for stabilizing these ever-hopeful patients before their view of their world blurs into legal blindness.

|

The Basics

For now, your choices when a patient’s vision isn’t getting better are bevacizumab (Avastin), ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Elylea) and brolucizumab (Beovu). As you know, successful treatment can depend on myriad factors, including administration frequency, drug selection, schedule management, novel treatments, recognizing masquerade syndromes and confronting special challenges, such as intraretinal and subretinal fluid management and the perplexing downturns triggered by tachyphylaxis. Retinal specialists say the keys to progress can be found in how you use these anti-VEGF medications. Validated by the definitive findings of randomized, prospective trials, the treatments are paradoxically used with broad variability in many practices, depending on a clinician’s experience, successes, failures and willingness to try something new.2

The continuing study of anti-VEGF therapy, at an individual level and as part of ongoing research, is what continues to drive patient care toward tomorrow, specialists say. In the words of J. Sebag, MD, FACS, FRCOphth, FARVO, a senior research scientist at the Doheny Eye Institute/UCLA and a professor of clinical ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA: “Research and clinical trials provide the scientific basis of our approach to patient care in this area of our practices. But individualizing patient care is what enables us to also practice the art of medicine.”

Most retinal specialists point out that the possibility of producing no response or a partial response with the injection of anti-VEGF medication is rare. “Virtually all patients who have neovascular AMD are sensitive to anti-VEGF therapy,” notes David Boyer, MD, senior partner at the Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group, based in Los Angeles and surrounding areas. Nonetheless, safeguarding against less-than-adequate results remains a high priority.

|

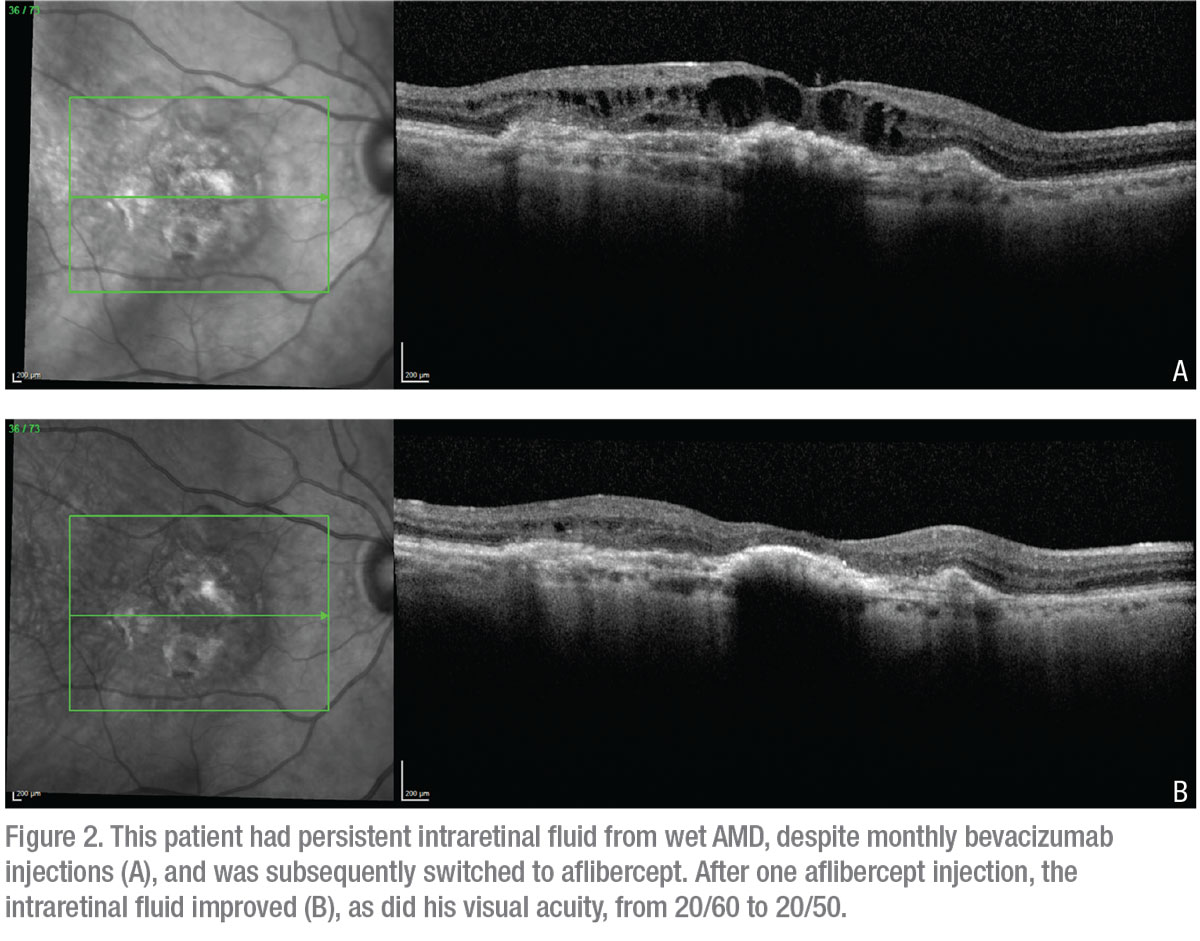

Responding to Poor Response

If Dr. Boyer sees evidence of no response after one treatment, he immediately changes therapy. “I usually start my patients on Avastin or one of the branded medications, if needed,” he explains. “If I see that the patient isn’t doing well one month later, I make a change to Eylea or Lucentis and have the patient return in two weeks.” (Although approved dosages are monthly for Lucentis and once every two months after three months of initial treatment for Eylea, Dr. Boyer has found little difference between these two agents in these situations.)

If he finds even the slightest response in a recalcitrant wet AMD case two weeks after the replacement treatment, he labels the patient a “poor responder” and proceeds with a customized approach to continuing to provide anti-VEGF therapy. “This disease is not like diabetes, which might not respond at all to an injection,” he points out.

Chirag Shah, MD, MPH, a partner at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston, says he often takes a “modified stepwise approach” to patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration who don’t respond to initial therapy, relying on a number of strategies. “In general, I start patients on Avastin because it’s an affordable and effective drug,” he says. If he’s not satisfied with the initial response, he considers switching patients to Eylea or Lucentis, each of which, he notes, has a greater pharmacological binding affinity to VEGF when compared to Avastin.

Like Dr. Boyer, he’ll also try a two-week interval, although not necessarily after only one failed treatment. “In this situation, I often alternate between Avastin and Lucentis or Eylea every two weeks, enabling twice-a-month dosing,” Dr. Shah explains. “Some insurance plans will cover both treatments each month. For other plans, I may need to absorb the cost of Avastin and only bill for the on-label drug. In my practice, however, this approach is very uncommon and only reserved for very aggressive wet AMD cases.”

Carl Regillo, MD, chief of the retina service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, also occasionally administers anti-VEGF agents every two weeks for challenging cases. “I do this mainly to determine whether I’m dealing with a condition that’s VEGF-responsive and to find out if the patient’s therapeutic effect is wearing off in fewer than 30 days,” he notes. “Sometimes that’s the case, but rarely. During this 30-day period, you need to ensure continuous VEGF blockade.

“Of course, there are exceptions to everything,” he continues. “You may discover a slightly better effect at week two than at week four, which implies that the medication is wearing off a little too quickly. We do this early on in the treatment of patients who aren’t responding as well as we’d hoped they would. When you’re finding significant exudation or experiencing a suboptimal response, you must first make sure you’re administering the drug as frequently as it needs to be administered. You test the waters. But in my experience, it’s very rare that you have a patient receiving injections less than every 30 days.”

Dr. Regillo is reluctant to quantifiably describe the advantages and disadvantages of today’s wet AMD therapies. “These drugs are more alike than different,” he notes. “There’s no study that shows significant differences in efficacy, safety or even durability. Anecdotally and in practice, we appreciate and sometimes see some different effects—one may provide a little bit more drying, a little bit more durability or be a little bit longer acting, for example. But when we first start using any one of these drugs to treat a patient’s onset of AMD, we almost always see some reduction in exudation.”

When a patient’s wet AMD is well-established by a previous response to anti-VEGF therapy or the presence of neovascularization is confirmed by OCTA, Dr. Regillo uses alternative anti-VEGF medications, intensifying therapy after three or four non-productive injections of his initial choice of medication. “Interestingly, the newer drugs do seem to have a little more of a drying effect than the earlier ones,” he notes. “Anecdotally, we’ve seen this effect progress from Avastin to Lucentis and then to Eylea. Now, Beovu seems to dry a little more than Eylea. The OCT results show a greater degree of reduction in OCT central retinal thickness.

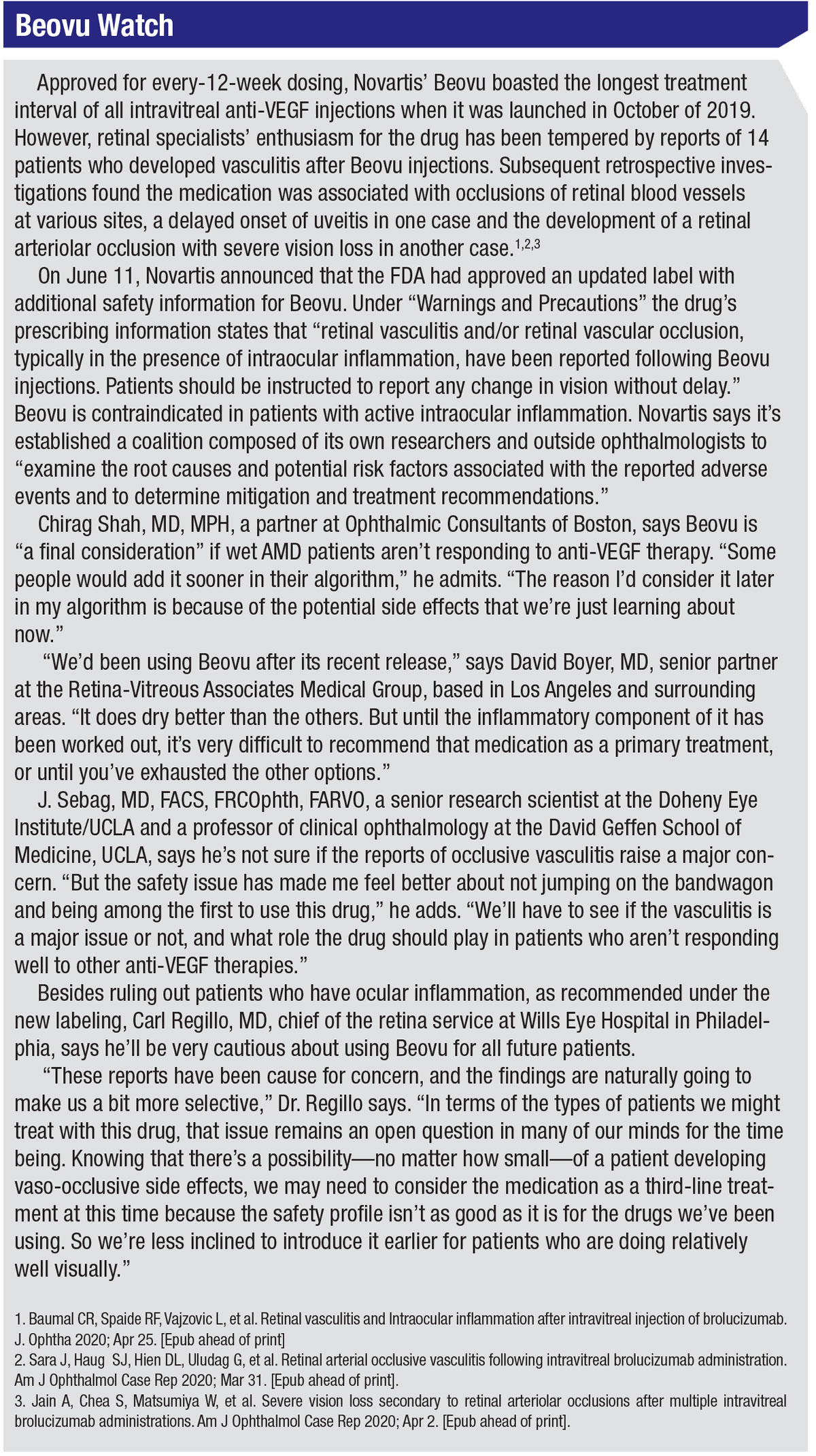

“Subsequent subgroup analysis from the phase 3 studies has shown that Beovu dried at a greater and faster degree,” he adds. “So at this stage, if the drugs I’m using don’t adequately dry up a patient’s exudation, I’ll consider using Beovu, but I’ll need to do so with great care, now that we’ve seen recent safety issues come to light with this new drug. In the context of new FDA labeling and risks that have surfaced, I’ll need to be certain I’m selecting the right patients who might benefit from this medication.” (See “Beovu Watch” below.)

Dr. Sebag says he’s eager to learn more about the comparative effects of Beovu and Eylea from the MERLIN study (Study of Safety and Efficacy of Brolucizumab 6 mg Dosed Every 4 Weeks Compared to Aflibercept 2 mg Dosed Every 4 Weeks in Patients With Retinal Fluid Despite Frequent Anti-VEGF Injections), the results of which he expects will be released in 2021, following a COVID-19-related delay of a planned 2020 release. “The purpose of this study is to compare Eylea to Beovu in patients who aren’t responding to long-term anti-VEGF therapy,” he notes. “It’s perfectly in line with what we’re discussing here.”

|

When Persistence Pays Off

Unlike most of his peers, Dr. Sebag’s typical approach to wet AMD patients who don’t respond sufficiently to anti-VEGF therapy is to continue with injections. “The first thing I would say is that I don’t jump to conclusions, even after my patient has undergone four or five treatments,” he notes. “I usually try to go longer before concluding that a patient isn’t responding to my approach.”

Dr. Sebag recalls one patient, a frail seamstress in her 80s, who was intent on regaining visual acuity. She endured 10 injections of Lucentis over 10 months, achieving no change in her 20/200 vision. “I told her she had been a really good patient but that she was not responding,” he says. “Then I told her I really didn’t want to put her through any more duress.”

The patient pleaded for a few more injections, to which Dr. Sebag agreed. “Little by little, with continuing injections, her visual acuity remarkably improved to 20/20,” he recalls. “She began to sew again. I was totally amazed. It taught me a lesson about how difficult it is to translate the results of clinical trials to a given individual. The only way you’re going to be able to approximate the results of a clinical trial is if you’re dealing with a patient who’s exactly the same as the ones in the clinical trial.”

Dr. Sebag now individualizes all of his treatment regimens, declining to stringently adhere to the results of when clinical challenges compel him to try a new approach. “For example: I have eight or nine patients who initially responded to monthly treatments, successfully extended, then stopped responding,” he says. “I went back to monthly treatments and they still didn’t get better. I proposed to them that we inject every two weeks for three to four months. So I used a half of a dozen injections to jump start their systems to see if that would work, which, anecdotally, it did. These patients received samples alternating with a standard drug treatment covered by insurance, which only pays for treatment intervals of 28 or more days. This approach seemed to get these patients back on track. They went back up to monthly injections and then once every two months.”

More Novel Approaches

Like Dr. Sebag, other specialists also use individual approaches to managing recalcitrant wet AMD patients. Below is a summary of a few:

• Increasing doses. A higher dose of the anti-VEGF agent can sometimes help produce a better response in suboptimal responders, according to Dr. Shah. “For me, this isn’t possible when treating with Avastin,” says Dr. Shah, who uses this technique as part of his modified stepwise approach to non-responders. “We get Avastin from a compounding pharmacy and there isn’t enough volume of the drug in the syringe to administer a higher dose. For Eylea and Lucentis, though, I can administer a higher dose. Instead of the standard 50 microliters, I can inject 75 or 100 microliters. Although the HARBOR study didn’t show an advantage of 2 mg of Lucentis compared to the standard dose of 0.5 mg, we find that a higher dose can sometimes dry the macula better in clinical practice.”3

• Adding topical dorzolamide hydrochloride-timolol maleate (Cosopt) to the mix. Dr. Shah says the additive effect of this topical glaucoma medication can enhance anti-VEGF therapy in recalcitrant cases, helping to decrease macular leakage. “Jason Hsu and colleagues [including Dr. Shah] found that this therapy can help in this way,” says Dr. Shah, describing this third strategy in his stepwise approach to these cases.4 He notes that the reasons the medication helps some patients aren’t known, although Cosopt includes a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which could play a role, as well as a beta blocker that might help improve the effectiveness of the anti-VEGF drug at the receptor level. “Through the action of aqueous suppression, Cosopt could also potentially help reduce clearance of the anti-VEGF drug from the eye, allowing its extended presence to continue to better dry the macula,” he adds.

• Overcoming the paralysis of tachyphylaxis. Dr. Boyer says tachyphylaxis can initially signal apparent treatment failure. “You’re injecting a stable patient once every three months, then the effects of the treatment suddenly only last two-and-a-half months,” he notes. “Next, it’s two months and it goes down from there, losing its effect. No one knows why this occurs. In these cases, you just need to replace the medication you’re using with another one. Patients will start responding again and you can actually return to the initial medication at some point, if you wish. This occurs in only 5 to 10 percent of patients. Usually, the biggest problem for wet AMD patients is that we don’t treat them frequently enough. So you want to make sure tachyphylaxis doesn’t lead to undertreatment.”

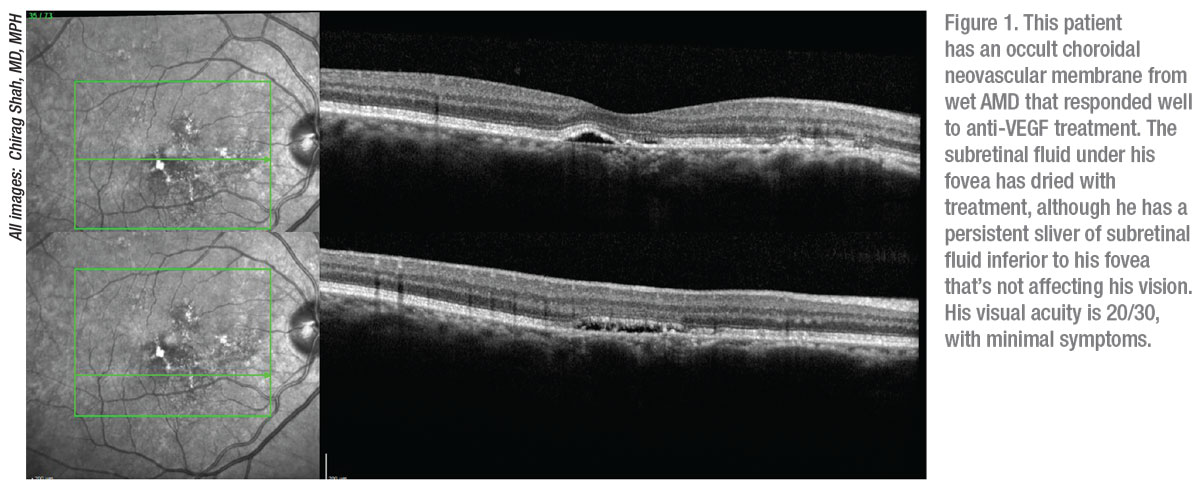

• Managing fluid. One of Dr. Boyer’s treatment goals is to eliminate intraretinal fluid, which he notes is a dangerous threat to vision. On the other hand, “if you’re treating a patient and subretinal fluid persists but the patient continues to have good vision, that’s usually tolerable,” says Dr. Boyer. “But you don’t stop treating the patient. Reports show that subretinal fluid is not detrimental but also that patients are continuing to be treated to get rid of the fluid. In these cases, the doctors just couldn’t eliminate the fluid. It’s not that they gave up on treatment. You have to be careful about this, but it’s true that subretinal fluid doesn’t bother vision as much as intraretinal fluid. It’s not affecting vision, so you’re not as concerned about it.”5,6

Although improvement and good visual outcomes usually go together when you’re drying the macula, Dr. Regillo points out that getting the macula completely dry is not always necessary. “That being said,” he continues, “when we see fluctuating fluid or decreasing vision and increasing intraretinal fluid in particular, we need to do a better job of reducing the exudation to a limited amount. We have no other choice but to switch among the anti-VEFG drugs. Whichever drug you choose first, you need to consider trying another and then trying another. At first, you should try them very frequently—every four weeks, sometimes more frequently, to see if the fluid is anti-VEGF responsive. It’s possible that no agent will completely dry the macula.”

• Maximizing frequency. When he sees unwanted regression during his evaluations, Dr. Sebag reviews the history of the patient’s frequency. “If the patient hasn’t responded, I find that frequency is usually the primary reason,” he notes. “It seems you’re never able to maximize frequency. I usually start with monthly injections for three months in a row before I transition to injections of Eylea every two months.”

He typically prefers to eventually start patients on a treat-and-extend protocol, when possible. “It’s quite variable from patient to patient,” he notes. “No matter how you design treatment, however, a lot of factors can disrupt the schedule—patients not getting a ride to the office, patients feeling ill, conflicting doctors’ appointments. All kinds of issues can interfere with the treatment you design.”

|

Masquerade Ball

The manifestations of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, central serous chorioretinopathy and other conditions can be present in the retina, disguised as the signs and symptoms of neovascular disease until their true identities are identified and responded to accordingly. “A number of masquerade syndromes can mimic the findings of a neovascular disease,” says Dr. Boyer. He identified the primary offenders:

• chronic central serous chorioretinopathy;

• polypoidal disease;

• adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy;

• macular telangiectasia;

• acquired vitelliform maculopathy;

• basal laminar drusen; and

• acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy.

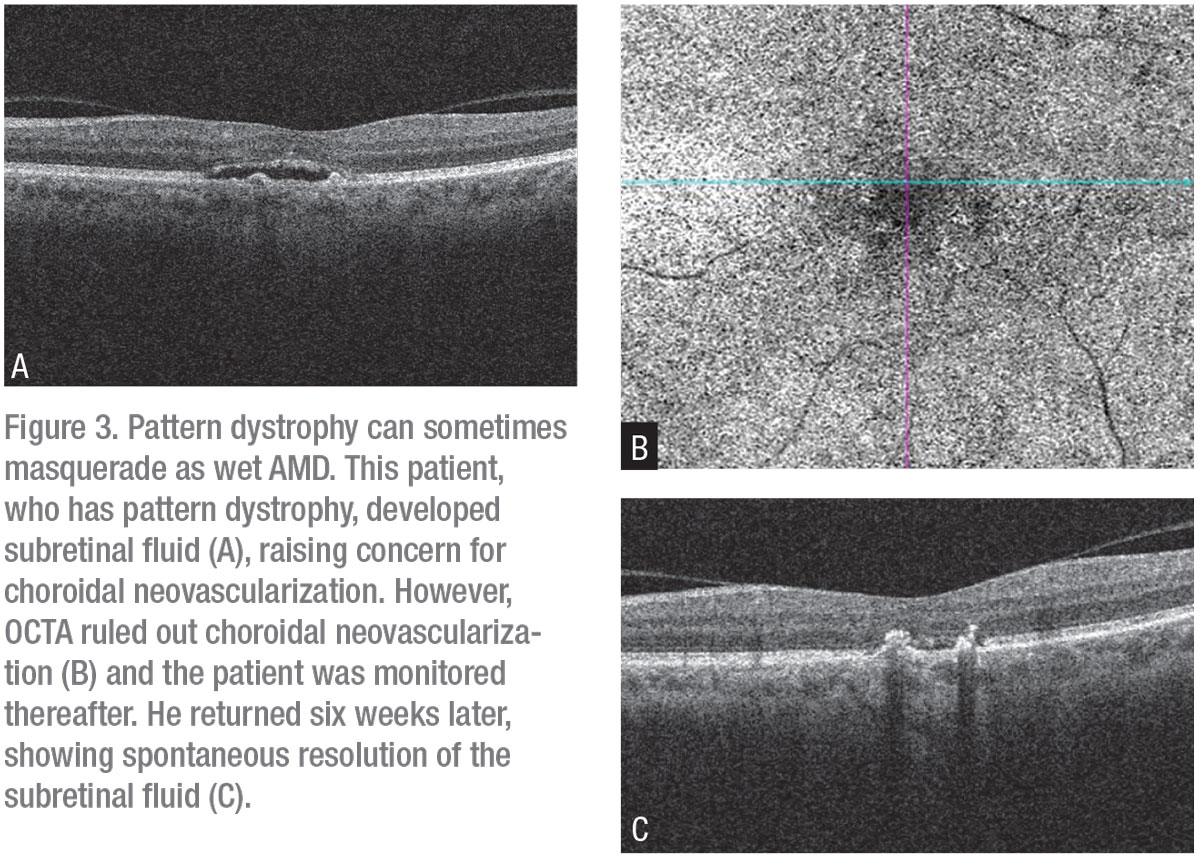

“We’ve seen lesions sent to us that have resulted in totally unexpected findings,” he continues. “One turned out to be associated with lymphoma. These are the types of patients who wouldn’t respond to anti-VEGF therapy. So, when I see this, I rework them up, getting an OCTA, which I find is usually helpful in identifying some of these conditions. Of course, I always look for these unusual findings at baseline, but sometimes they’re not initially obvious.”

Macular dystrophies are among the other classic examples of these distractions that Dr. Regillo has diagnosed. “Patients may get started on anti-VEGF and the response is not seen,” he says. “So the first thing I ask myself when I don’t see any response: ‘Is the diagnosis correct?’ ICG angiography is superior to fluorescein angiography in helping us view the choroidal base for choroidal lesions. If you see the polyps and you’re not seeing an adequate response to anti-VEGF therapy, then adding photodynamic therapy is a potential option for you to consider. It’s very rarely used now, but it’s an option in these cases.”

In a “desperate situation,” Dr. Boyer says he will also use PDT. “Then, though, you run the risk of creating a scar, depending on the thickness of the choroid. If the choroid is thick, you can get away with it, but if it’s not, the use of PDT may not be best. And it’s important to always remember that the visual results of PDT are nowhere near the level of quality that we can achieve with anti-VEGF therapy.”

Dr. Shah modifies PDT to minimize risks in these cases. “As we all know, PDT involves intravenous administration of verteporfin, which is activated in the retina by a non-thermal laser,” he says. “I often use half-fluence laser, which can yield a similar response to full-fluence laser but with reduced complications, such as an episode of choroidal hyperperfusion that can lead to darkening of the central vision.”

Best You Can Do

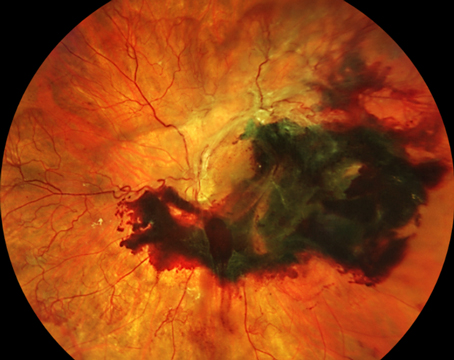

In a complex interweaving of pathologies, Dr. Boyer says that he’s seen neovascularization that’s led to a retinal and choroidal anastomosis. “These patients continue to leak and you unfortunately aren’t going to be able to stop this leaking,” he says. “The blood vessels are large and probably not sensitive to anti-VEGF factors. These patients are end-stage or patients who have had AMD for a long period of time.”

In the final analysis, retinal specialists agree, the best you can do for these patients is to keep trying all therapeutic options and remain open to improvements in safety and new treatments on the R&D horizon. “We can’t give up on our patients,” says Dr. Sebag. “We must always find ways to keep trying to help them see better.” REVIEW

1. Maguire MG, Martin DF, Yinggs, et al, for the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group. Five-year outcomes with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: The comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology 2016;123:8:1751-1761.

2. Erie JC, Barkmeier AJ, Hodge D, Mahr MA. High variation of intravitreal injection rates and Medicare anti-vascular endothelial growth factor payments per injection in the United States. Ophthalmology 2016;123:6:1257-62.

3. Busbee BG, Ho AC, Brown DM, et al, for the HARBOR Study Group. Twelve-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013;120:5:1046-56.

4. Hsu J, Patel SN, Wolfe JD, et al. Effect of adjuvant topical dorzolamide-timolol vs placebo in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2020;138:5:560.

5. Guymer RH, Markey CM, McAllister I, et al, for FLUID Investigators. Tolerating subretinal fluid in neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with ranibizumab using a treat-and-extend regimen: FLUID study 24-month results. Ophthalmology 2019;126:5:723-734.

6. Sharma S, Toth CA, Daniel E, Grunwald JE , et al. Macular morphology and visual acuity in the second year of the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology 2016;123:4:865-75