Uveitis is one of the most challenging diseases to treat, both in its infectious and non-infectious forms. Specialists who regularly help manage the condition have to consider the many types of uveitis and the various therapeutic pathways that are available, some of which come with considerable side effects and can take years to work fully.

In this article, experts discuss the more severe cases of uveitis and the treatment plans that work best.

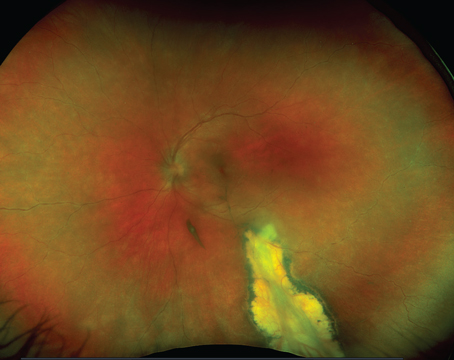

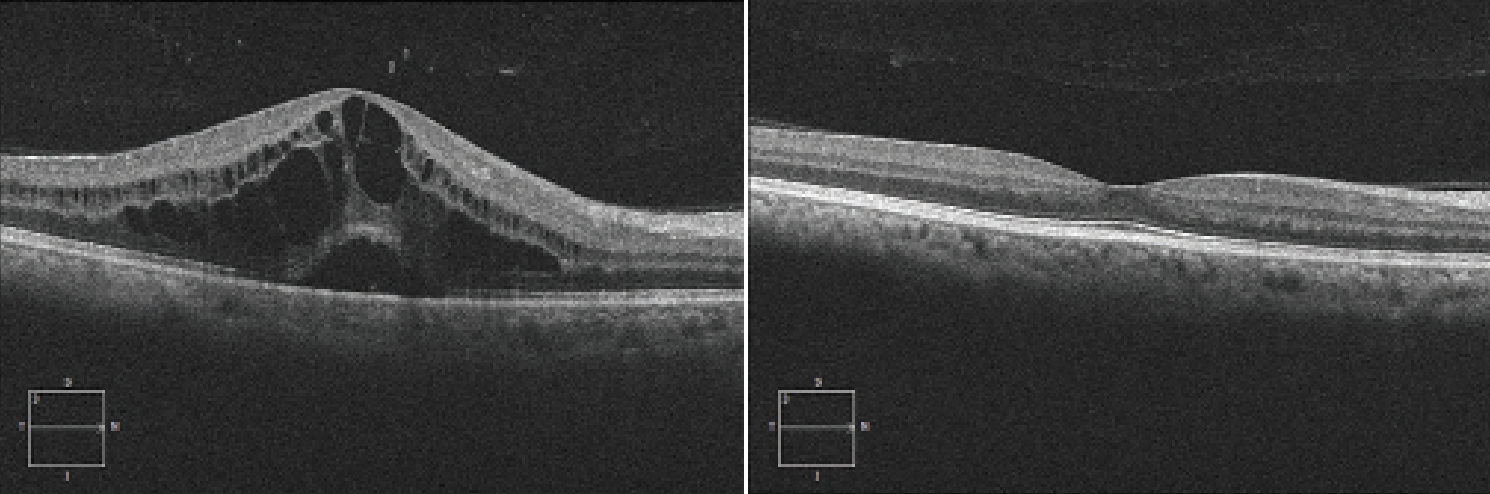

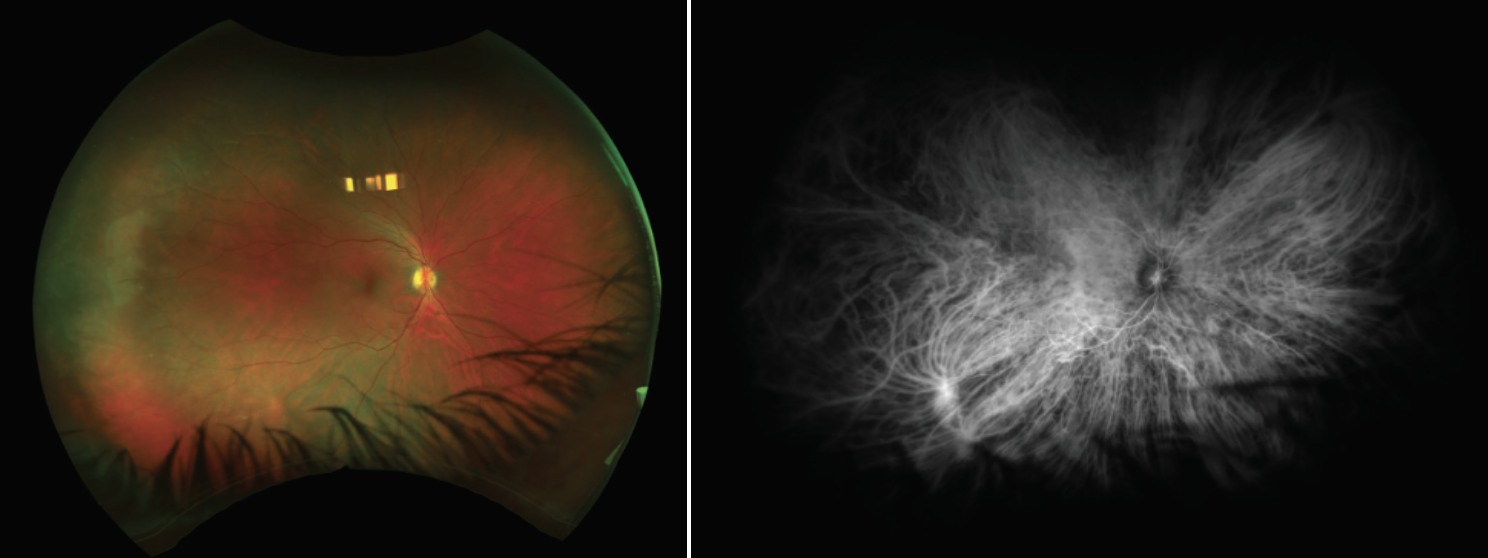

|

| The image on left demonstrates 4+ uveitic macular edema with a subretinal fluid component. The image on right shows macular edema resolution after treatment with intravitreal steroids and immunomodulatory therapy. (Courtesy Sam S. Dahr, MD, MS) |

Categorizing the Uveitis

“I think the trickiest thing is that uveitis is heterogeneous,” says Christopher R. Henry, MD, a medical and surgical retina specialist practicing in Houston. “Uveitis encompasses hundreds of different ocular conditions which can be autoimmune, infectious or a masquerade. There’s a broad spectrum in terms of how serious a disease is, how much of a risk to sight it is, and there’s a really broad range of treatment strategies. For instance, a problem such as an isolated, unilateral, acute anterior uveitis can be very easy to treat, but bilateral, severe, chronic panuveitis will likely be a lot harder.”

In a way, the challenge can be exciting, according to Sruthi Arepalli, MD, an assistant professor in the Vitreoretinal and Uveitis Service at Emory University. “What attracted me to the field of uveitis is that no two patients will present exactly the same, and that keeps the job fun,” she says. “Despite this, there are overarching similarities, which allows us to rely on pattern recognition while teasing out their nuances. These nuances include a different constellation of systemic signs, or maybe their ocular manifestations and complications aren’t exactly the same as the person before them. These differences can dictate treatment algorithms. The field of uveitis becomes an art of balancing their manifestations, medication side effects and patients’ short- and long-term goals.”

Dr. Henry says there are some key factors to examine before proceeding with treatment. “You’ll want to assess how serious the disease is,” he says. “You’re going to look at:

- is it unilateral or bilateral disease;

- the anatomic location: anterior; intermediate; posterior; or panuveitis;

- is it an acute disease or chronic;

- how aggressive the process is;

- the degree of vision loss at baseline; and

- how likely is this to progress quickly?

“For the majority of cases I’ll usually order lab testing—unless it’s a straightforward, isolated anterior uveitis—to try to figure out the cause. The lab work will really be driven by the clinical appearance of what the disease looks like,” Dr. Henry says.

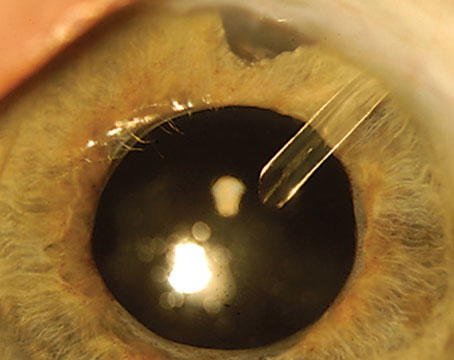

|

| This 58-year-old female presented with a 30-year history of idiopathic intermediate uveitis. Vision is currently 20/200 bilaterally. The patient had a documented history of macular edema in the first 10 to 15 years of her disease course treated with topical steroids only. This case demonstrates that undertreated macular edema may develop foveal thinning and central vision loss. |

Dr. Arepalli first rules out infection. “My first rule of thumb when I’m seeing a uveitis patient is to rule out an infection or masquerade condition,” she says. “While masquerades can take a while to present themselves, infectious causes should be ruled out immediately. Emory is a big referral center for vitreoretinal lymphoma and I often get referrals for uveitis that isn’t improving with the standard regimen, so I think about masquerades a lot.”

“For severe disease, once you’re sure it’s noninfectious uveitis, most of those patients will need more than just topical steroids, and that can include oral steroids, local steroid injections, and some patients will need systemic immunosuppression,” says Dr. Henry.

Steroids, Immunomodulators or Both?

Starting off with steroids is common, say experts. “I’d say the majority of times you’ll treat with both topical and oral steroids initially and then depending on what the lab work-up shows and how a patient responds, and whether the disease is likely to be chronic or vision-threatening, then you may need to transition them over to a longer term steroid-sparing agent,” says Dr. Henry.

Dr. Arepalli gathers information while initiating steroids. “I’ll typically first start with topical steroids for two reasons: First, I’m building a relationship with this patient, so it gives me an opportunity to see how they tolerate a regimen and see how compliant they’re going to be,” she says. “It’s also an easy thing to stop if something surprises me in their workup and I want to change directions. Lastly, it helps me test how they’re going to react to steroids, like if they will develop a pressure response.”

More often than not, her patients will need treatment with immunomodulators. “At Emory, I’m often seeing tertiary referral patients, and they’ve failed topical or oral steroids,” Dr. Arepalli says. “With these patients, I often graduate them to immunosuppression or local therapy pretty quickly because I can see evidence of uncontrolled inflammation.”

For aggressive disease, it often requires early and aggressive management, Dr. Henry says. “A common mistake that doctors make is to undertreat. You want to squash the inflammation quickly and taper in a structured manner. Where you actually run into more trouble is if you don’t quiet it quickly and you let it linger,” he says. “I think patients end up doing more poorly that way. If you do keep them on topical steroids for a long period of time, it’s critical that you monitor the eye pressure. If a patient is a steroid responder you need to be on top of that and treat that as well.”

Moving forward with long-term immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) is a major decision. “What are the thresholds that prompt the treating ophthalmologist to recommend IMT?” asks Sam S. Dahr, MD, MS, the director of the retina division in the Ruiz Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science at the University of Texas Health Houston McGovern Medical School. “In cases of chronic or recurrent anterior uveitis, prevention of anatomic sequelae such as inflammatory glaucoma, cataract, progressive posterior synechiae, peripheral anterior synechiae, band keratopathy and macular edema may also indicate IMT. Regarding intermediate uveitis, chronic macular edema that repeatedly recurs after local therapy with an intravitreal steroid injection is often an indication for IMT. In cases of posterior uveitis or panuveitis, macular edema, chorioretinal scarring, inflammatory choroidal neovascularization, inflammatory retinal degeneration, visual field loss or severe retinal vasculitis can be indications for immunomodulatory therapy.

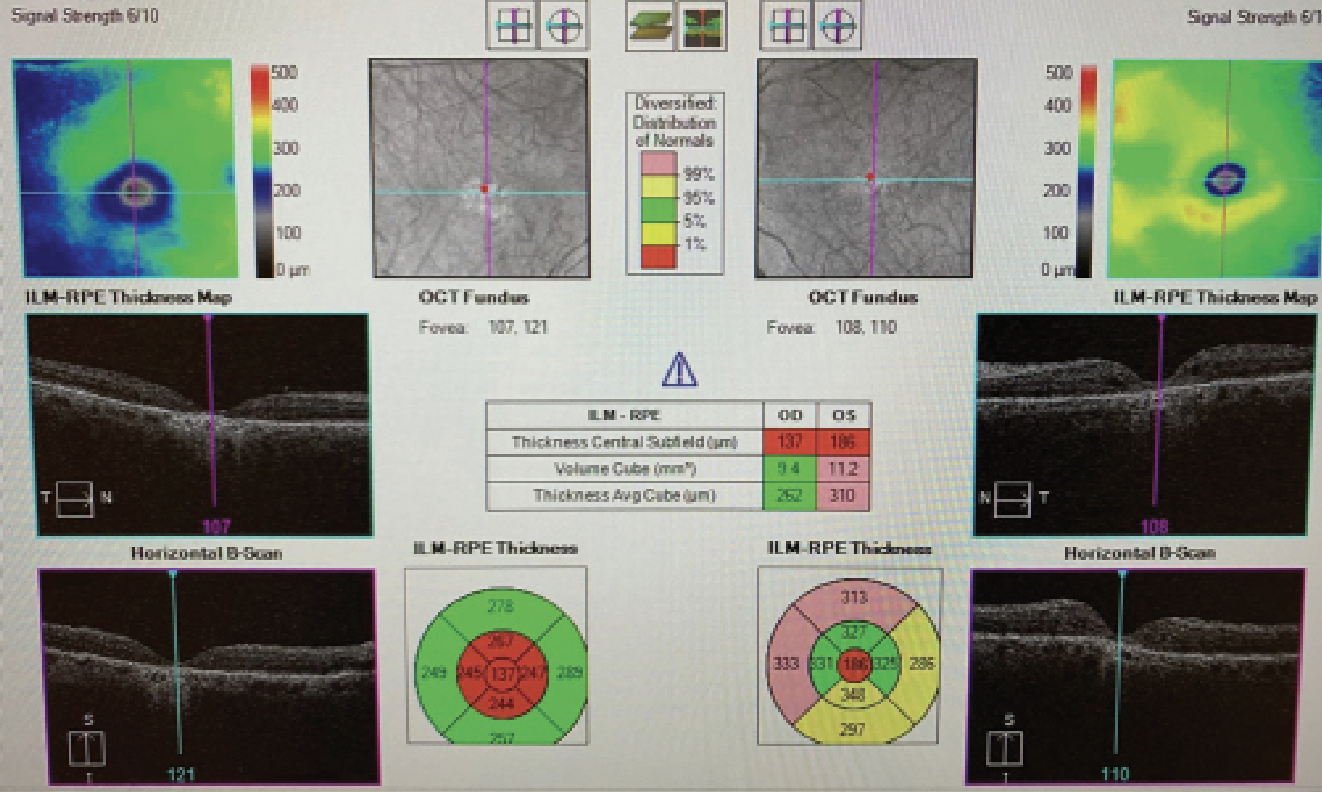

“To answer the question of whether or not to initiate IMT, we really use all of our metrics,” he continues. “We use our ophthalmic exam. We may use OCT, the fluorescein angiogram, and visual fields. If we have a sense that the disease is progressing or is going to progress because of the nature of the disease, then we have to step up and go in the direction of immunomodulatory therapy.”

Due to her uveitis fellowship training, Dr. Arepalli says she has a low threshold for immunosuppressives. “In general, we’ve seen in the uveitis literature that the ‘see-saw’ effect, or those situations in which we chase flares with steroids rather than preventing them, results in worse outcomes,” she says. “In particular, if a patient has bilateral disease or disease in their good eye that’s encroaching on their central vision, I push for immunosuppression. We have really good data from the SITE (Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Disease) study that has shown us that when you get complete control of posterior or panuveitis with immunosuppression, you can significantly decrease the complications from uveitis, particularly things like choroidal neovascular membrane formation. That data also shows us that you don’t get that same effect if patients are minimally controlled, meaning that we let them smolder and they’re not completely quiet. That forms my treatment paradigm and I lean on immunosuppression earlier, because I know that we get better results.

“Also, I see a good number of pediatric uveitis patients, and in addition to balancing everything we’ve already discussed, I’m also trying to keep them with good vision and functioning for as long as possible,” continues Dr. Arepalli. “Therefore, I may opt for immunosuppression earlier in these patients as well to prevent long-term complications from their uveitis.”

SITE was a retrospective cohort study showing that, one year after starting IMT, sustained control of inflammation was attained in 62.2 percent, 66 percent, 73.1 percent, 51.9 percent, and 76.3 percent of patients taking azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine and cyclophosphamide, respectively.1 It also revealed that the rate of inflammatory control dropped when oral prednisone was stopped, regardless of the IMT agent used.

|

| A 53-year-old male was treated by a physician for recurrent anterior uveitis, but referred for poor control with topical steroids. The patient was treated with local steroids for years. On dilated eye examination, there was a small amount of vitreous cell, and while the fundus examination was fairly bland, an ICG revealed a multitude of choroidal granulomas. A review of systems revealed that the patient had a history of tattoos that would periodically swell, and chest imaging was consistent with sarcoidosis. The patient was started on immunosuppression and has done well since. |

Antimetabolites, Biologics and More

We asked these experts about the combination of agents they typically turn to first for patients with noninfectious uveitis.

“With immunosuppression, we have a lot of different treatments that we can consider,” says Dr. Arepalli. “There are antimetabolites, which tend to be the first-line therapy, and that’s made up of methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate. Then you’ve got your biologics like adalimumab and newer drugs as well. You also have other therapies, including alkylating agents or calcineurin inhibitors and each one of those carries a very specific panel of side effects. It’s a matter of matching what the patient wants and can tolerate with what the side effects of those treatments are.” (More on side effects later.)

“In the era before anti-TNF inhibitors such as Humira (adalimumab), and Remicade (infliximab), we would often use an anti-metabolite plus a T-cell inhibitor,” says Dr. Henry. “But now, we generally start a patient with an antimetabolite such as methotrexate or mycophenolate, and we have good Level I evidence for that pathway from the FAST trial.”

FAST (First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment) was a trial that screened 265 adults with noninfectious uveitis who were randomized to receive oral methotrexate, 25 mg weekly, or oral mycophenolate mofetil, 3 g daily. In the posterior or panuveitis patients, treatment success occurred in 74.4 percent of patients in the methotrexate group vs. 55.3 percent in the mycophenolate group, whereas 33.3 percent of those with intermediate uveitis had success with methotrexate vs. 63.6 percent with mycophenolate.2

“The two first-line agents I use the most often are antimetabolites (such as methotrexate, mycophenolate or azathioprine) and biologic agents,” Dr. Henry says. “The anti-TNFs are probably the most common biologic that I use: Humira; Remicade (infliximab); Simponi Aria (golimumab); or Cimzia (certolizumab pegol). For more aggressive diseases, I’ll sometimes use rituximab.”

Dr. Dahr says approximately 40 to 60 percent of patients will need combination therapy. “Then we typically add the anti-TNF agent to the antimetabolite,” he says. “This pathway has become acceptable for both children and adults: first, the antimetabolite and then, as needed, go to combination therapy and add the anti-TNF agent.”

Some patients who need combination therapy may not tolerate the antimetabolite, or they may not tolerate the anti-TNF, continues Dr. Dahr. “In those patients, we could consider a T-cell inhibitor such as tacrolimus or cyclosporine as a component of combination therapy. Even though it’s a steroid and is injected into the vitreous as a form of local therapy, the Yutiq (fluocinolone 0.18 mg) implant features a long duration of action (two to three years) and can function as a building block in a long-term treatment regimen,” he says. “Hence, many different combinations exist. For example, an antimetabolite plus a T-cell inhibitor is a classic combination that can work well and is inexpensive. As another combination, we may use a Yutiq implant in conjunction with an anti-TNF in a patient who doesn’t tolerate the antimetabolite but needs more than the anti-TNF alone.”

Dr. Henry says he rarely uses T-cell inhibitors, such as cyclosporine. “There are some uveitis specialists who use that regularly, but in my practice, I use it very sparingly,” he says. “I typically will use mainly antimetabolites and biologics and then supplement with local steroids if they need extra control.”

“T-cell inhibitors and alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil) are, in my mind, the heaviest hitters,” says Dr. Arepalli. “I’ve reserved those for patients who have the most severe disease. I really rely on rheumatology for going down that route because they can cause a lot of side effects. I have a handful of patients who are on alkylating agents. One that comes to mind is a patient who has a terrible case of scleritis in the setting of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. We had gone through everything else and ended up on cyclophosphamide because she just couldn’t get controlled any other way. So while they’re older drugs and they’re among the harshest drugs we have, they’re still very useful on patients for whom you can’t get control with some of our newer medications.”

Interleukin-6 inhibitors are a new frontier for treating noninfectious uveitis. “IL-6 antibodies, like tocilizumab, are relatively new,” Dr. Arepalli continues. “I’ve had really nice success in certain patients, particularly those with posterior uveitis and uveitic macular edema. We also have studies that are looking at the intravitreal administration of IL-6, such as DOVETAIL, a Phase I study, with positive results.”

Preliminary results from the Phase I DOVETAIL study showed injection of RG6179 resulted in improvement in both vision and retinal thickness in all dosing cohorts, and was well-tolerated.3

In terms of future therapies to watch, Dr. Arepalli believes IL-6 is the most promising right now. “DOVETAIL showed a significant reduction in uveitic macular edema with intraocular administration,” she says. “Traditionally, intravitreal treatment for uveitic macular edema requires steroids, so this presents an opportunity to do a local, steroid-sparing treatment.”

Dr. Henry mentions that patients are currently in clinical trials for janus kinase (JAK or JAK/Tyk2) inhibitors. “It can be another tool in our toolbox,” he says. “There’s a lot to learn in uveitis. As we gain more knowledge about different disease entities, we may find that one systemic therapy has advantages over others for certain conditions.”

With any of these therapies, it’s best to discuss expectations with patients, not only regarding their efficacy, but also what’s expected of the patient while undergoing treatment.

“With the classic traditional agents such as the antimetabolites and the T-cell inhibitors, those often take three to six months to start to take effect, and their full effect may take six to 12 months,” Dr. Dahr says. “During that initial period we’re often using oral corticosteroids or some form of local corticosteroid injection in an ‘induction’ fashion until the immunomodulatory agent takes effect. With regards to the anti-TNFs, those work a little bit faster. We often start to see some effect within six to eight or six to 12 weeks. I explain to patients that we have short-term goals, medium-term goals and long-term goals. Of course, most patients desire to achieve drug-free remission in the future. Some patients can achieve that goal over a period of time; some patients can’t, but it certainly is a goal for which to aspire.”

When it comes to taking patients off of treatment, that’s an in-depth discussion, says Dr. Arepalli. “A lot of my younger patients are in their family-planning stages of life,” she says. “In these patients, we’ll talk to them about what is safe during pregnancy. I generally leave this up to rheumatology, but adalimumab has good evidence to be well-tolerated during the majority of pregnancy, and azathioprine is safe as well. I also tell patients that uveitis tends to calm down during pregnancy, so if they want to come off immunosuppression, we can try to treat locally or with oral steroids if necessary.”

“Our hope is that the corticosteroid essentially goes to zero, the immunomodulatory agents take effect and the disease remains controlled,” adds Dr. Dahr. “Once we achieve that status of the disease control and the patient is off the corticosteroid, we then essentially start a clock. Our goal is a minimum of one year and most specialists really like two years with essentially no need for corticosteroids. If a couple of years pass and the disease stays quiet with no need for corticosteroids, we may then consider a taper of the immunomodulatory agents. That’s the approach most uveitis specialists follow.

“I call that period the ‘cruise-control’ period,” he continues. “If the patient’s doing well—no corticosteroids, tolerating immunomodulatory therapy well, exam looks good—I will typically follow that patient every four months or so. Of course the patient is encouraged to call and come for an appointment should he or she perceive a flare up. If, upon a slow taper of IMT, the disease reactivates, one usually goes back to IMT (often with some corticosteroid re-induction) and tries again a few years later.”

Patients will also need to be monitored over the course of treatment. “Those on antimetabolites are going to need regular lab testing approximately every three months looking at a CBC and their liver and kidney function,” says Dr. Henry. “Once in a while, we can see liver enzymes go high with antimetabolites, or we can see the blood counts drop too low, so that’s something that needs to be regularly monitored.”

Dr. Arepalli says it’s helpful to work closely with rheumatology, especially if the patient has multiple medical conditions in addition to their uveitis. “Here at Emory, we have a lot of patients with multiple chronic and complicated systemic conditions, or they’re traveling from far away and it makes monitoring them hard to do by myself. In those patients, I really think it’s nice to work synergistically with rheumatology,” she says. “When monitoring these medications each one carries its own set of requirements. Most commonly, every drug requires a CBC and CMP. You’re often checking for anemia, low white blood cell counts, kidney function and renal function. Other medications might require that you get a urine analysis. There’s not one algorithm for every drug, it’s more personalized based on the mechanism of the drug.”

Tolerance and Side Effects To Expect

Side-effect profiles further complicate treatment of uveitis, and that goes for both steroids and immunomodulators. It’s best to have an open discussion with patients about the risks and benefits of pursuing treatment.

“I remind patients that they have a vision-threatening, sometimes debilitating disease and my job as a uveitis specialist is to put them on the medication that’s going to quiet their disease with the least amount of side effects,” says Dr. Arepalli. “I also remind them that when we coordinate with other subspecialities, it’s my job to update the other physicians on the status of the eyes, because these can flare up independently of the rest of the body, and that may mean that they need to change around their medications. I also set the stage when I first meet patients that their medication cocktail is going to fluctuate until we find the best fit for them, and this can take many months to years.”

Every single drug comes with side effects, including topical and local steroids. “With oral steroids, we have literature that shows that patients are often treated for too long and too high of a dose before they transition over to immunosuppression,” continues Dr. Arepalli. “Our literature also says that 7.5 milligrams or lower of oral steroids is the best tolerated long-term, but that’s often too low of a dose to get control of uveitis.”

Antimetabolites carry side effects that are typically well-tolerated, but become more serious depending on a patient’s lifestyle.

“Around two-thirds of patients tolerate anti-metabolites pretty well,” says Dr. Henry. “The most common side effects I see are probably fatigue or nausea on the day of treatment. If they’re not able to tolerate oral methotrexate, it’s also available in an injectable form. In my experience, biologics are really well-tolerated. Humira, for instance, is a shot that patients give themselves every two weeks and you need to get at least an annual chest X-ray but the lab testing and monitoring aren’t as intensive on a biologic. Some patients do experience fatigue, but many patients can’t even really tell they’re on a biologic. They feel normal. With Remicade, or other infusions given in an infusion center, occasionally we can see infusion or allergic reactions, so you do need to discuss this with patients in advance of this possibility.”

Depending on a person’s stage of life, there are some considerations to make about these medications and requires frank conversations with patients, says Dr. Arepalli. “This is by no means a complete review of the side effects or considerations for immunosuppression, but when I start the conversation with a patient, I mention a few key things,” she says. “When discussing antimetabolites, there are certain ones that you can’t prescribe if the patient is in the family-planning stages of life. Also, if you drink a certain amount of alcohol per week, you’re not a candidate for methotrexate. It’s really important that they’re open with me about those things so we can come up with the best plan with rheumatology.

“Occasionally, I’ll have a patient who’s been doing well on methotrexate, but now they’re interested in trying alcohol,” continues Dr. Arepalli. “In these cases, we can switch them from one antimetabolite to another, or to a biologic. Alternatively, I might tell them since they’ve been quiet for a few years we can talk to rheumatology about tapering the medications and seeing how they do.”

Even though there’s a lot for patients to think about, it’s best to remind them of the reliable and safe track record for these drugs. “We tell patients that all of these immunomodulatory medications have been used by hundreds of thousands of patients in the last several decades, and a Google search will find a broad spectrum of reported complications for any of the medicines we use,” Dr. Dahr says. “Certainly, those potential complications sound scary. What’s important to keep in mind is that the overall incidence of complications is low. There’s always a benefit-to-risk calculation that’s being made and the treating ophthalmologist and the patient should always discuss the benefit of a medication in terms of treating the uveitis and preserving vision vs. the risk. In most cases, the benefit-to-risk ratio for these severe uveitides favors using the medication, but no pathway is risk free. At the same time, losing vision in an irreversible fashion because of uveitis increases the risk of everyday life.”

This is exactly what uveitis specialists are balancing daily. “It’s helpful to keep in mind that this is all a balancing act of what we’re trying to achieve and the medication side effects,” says Dr. Arepalli. “Especially because we want to focus on the short term of controlling their inflammation, but also keeping them an active member of society by preserving vision and allowing every chance to enjoy their life. And if there’s concern that you’re not striking the right balance, it can be helpful to get a second opinion. Referring early can be really powerful.”

Dr. Arepalli is a consultant for AbbVie and Alimera. Dr. Dahr has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Henry is a consultant for Bausch + Lomb, Clearside Biomedical, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals and has previously consulted for Allergan.

1. Kim JS, Knickelbein JE, Nussenblatt RB, Sen HN. Clinical trials in noninfectious uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2015;55:3:79-110.

2. Rathinam SR, Gonzales JA, Thundikandy R, Kanakath A, Murugan SB, Vedhanayaki R, Lim LL, Suhler EB, Al-Dhibi HA, Doan T, Keenan JD, Rao MM, Ebert CD, Nguyen HH, Kim E, Porco TC, Acharya NR; FAST Research Group. Effect of corticosteroid-sparing treatment with mycophenolate mofetil vs methotrexate on inflammation in patients with uveitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;10:322:10:936-945.

3. Sharma S, Suhler E, Lin P, Pauly-Evers M, Willen D, Peck R, Storti F, Rauhut S, Gott T, Passemard B, Macgregor L, Haskova Z, Silverman D, Fauser S, Mesquida M. A novel intravitreal anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody for uveitic macular edema (UME): Preliminary results from the phase 1 DOVETAIL study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2023;64:8:5100.