Dealing with a malpositioned intraocular lens is always a challenge. Nevertheless, there are multiple options for dealing with a malpositioned three-piece IOL, including scleral and iris fixation. That’s not the case when the dislocated lens is a one-piece lens. In that situation—especially if the haptic is exposed—many surgeons would opt to remove the lens and replace it.

Recently, Kenneth J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the John A Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, and surgeon director at Fifth Avenue Eye Care and Surgery/Rosenthal Eye Surgery in New York, developed two new techniques for suturing a one-piece lens in place that appear to be safe and effective. Here, he shares how he proceeds when faced with this type of scenario.

The Problem

“If the patient has a malpositioned one-piece lens, it’s usually a bad idea to place it in the sulcus, where you could end up with apposition and resulting chafing between the haptics of the one-piece and the posterior iris,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “When deciding how to deal with this, it matters whether the haptic is exposed. If it’s a dislocated capsular bag/lens complex—in other words, if the lens and haptics are still within the capsular bag, but the zonules have let loose—then you can lasso the haptic and pull it in.

|

|

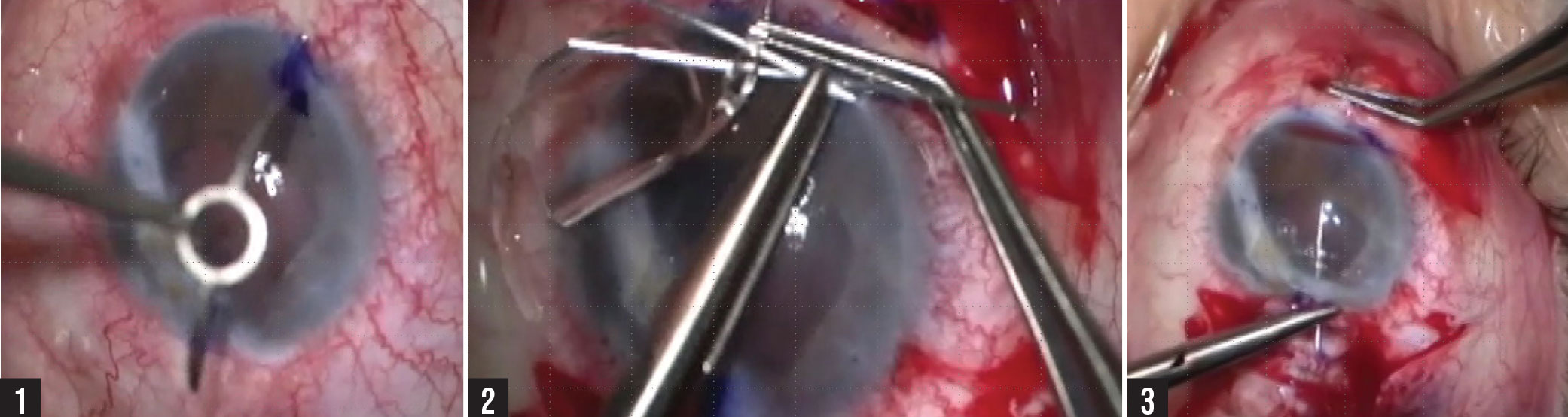

This patient, who had a previous penetrating injury, developed endophthalmitis following implantation of a toric lens. A vitreoretinal surgeon removed the lens, leaving the patient with high astigmatism. Because a corneal scar made treating the astigmatism at the cornea impossible, the original surgeon decided to replace the lens and suture the new one in place, using a new technique. 1) Marking the steep axis for the astigmatism. 2) Forceps hold the haptic of the new toric lens while two needles (for a double-armed 9-0 prolene suture) are passed through it. 3) The suture is passed across the eye and pulled out through a scleral groove placed 2 mm behind the limbus. |

“On the other hand, if it’s a bare haptic, it has to be handled differently,” he continues. “If you have a one-piece lens that’s been dislocated with the haptic exposed, that lens would normally be explanted, to avoid contact between the haptic and the posterior iris. You can’t just lasso it and suture it using standard techniques, because the likelihood of it rubbing on the back of the iris is too great.

“However, there are cases in which there’s a compelling reason to leave the lens in the eye, such as when it’s a toric lens,” he notes. “In the United States, at least, all toric lenses are one-piece acrylic. If you remove a toric lens and replace it with a spherical lens, the patient will be left with all the astigmatism the lens was correcting.

“For that reason, I’ve developed two surgical techniques for fixating the haptic in this situation—not previously published but presented at national meetings—in which the lens is repositioned with the haptic fixated to the scleral wall posterior to the iris, making sure that there’s no iris-haptic contact,” he explains. “This can be done using either of two techniques.”

The Two Techniques

Dr. Rosenthal explains that the first technique involves passing a suture—usually a polypropylene suture on a long, curved needle—through the haptic itself. “Most haptics are thick enough that you can actually pass the suture through the parenchyma or substance of the haptic,” he points out. (See photos.) “Then, you fixate the haptic in the posterior part of the ciliary sulcus, typically about 2.5 mm behind the limbus, inspecting it carefully to make sure there’s no contact with the iris. You can do this with an intraocular endoscope or an intraocular UBM.

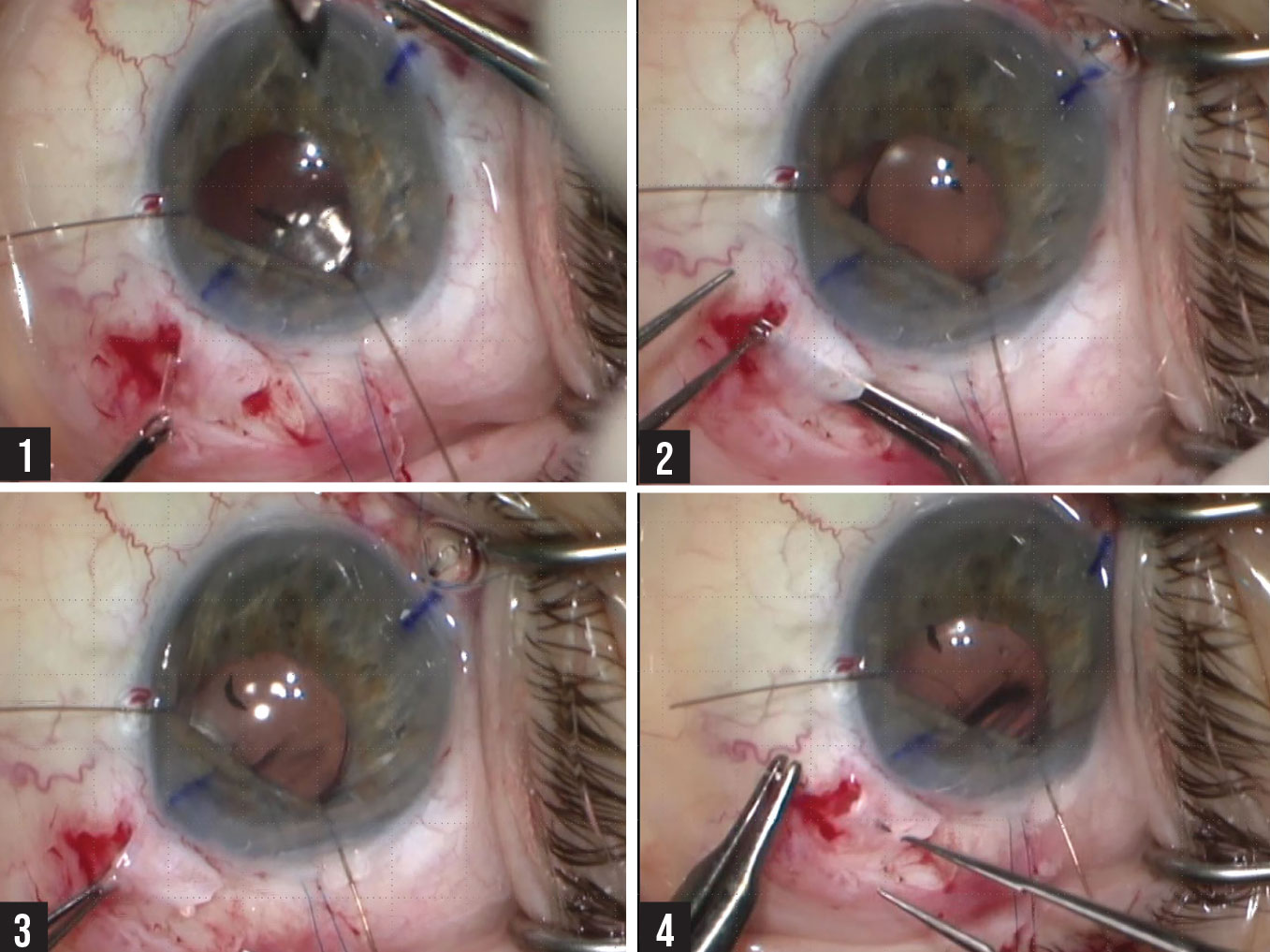

“The second technique involves a modified Yamane-style fixation of the one-piece lens,” he continues. “In standard Yamane, you withdraw the haptic to the scleral surface through the barrel of a 30-ga. thin-walled needle; with my modified one-piece technique, you make a 1-mm intrascleral groove and reach in and grasp the haptic and pull it out. Then you pass a suture through the haptic and then the sclera. (See photos, right.) Using this technique, we know where the haptic is, and it’s away from the back of the iris. (I’ve designed an instrument specifically for reaching in and grasping the haptic that’s not yet in production, but should be soon.)

|

|

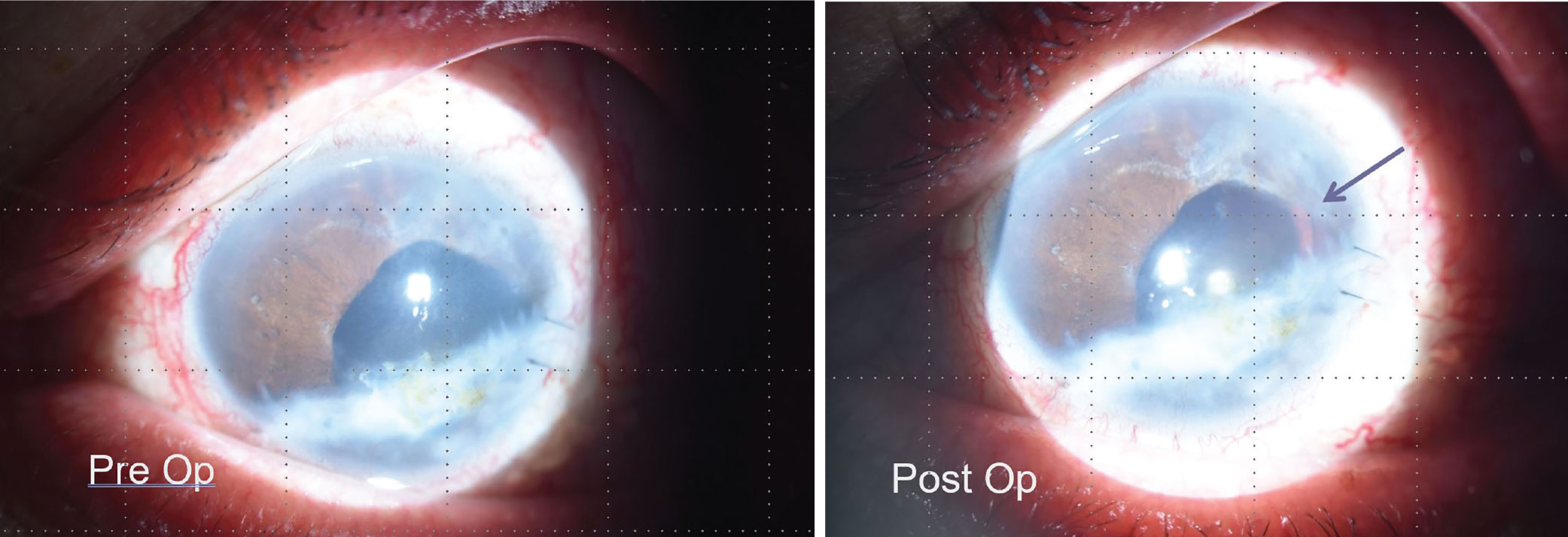

The eye shown in the series in the previous figure, before and after the procedure. The arrow points to the toric lens alignment marks. |

|

|

External one-piece haptic fixation. 1) The haptic is pulled out through the sclera. 2) The surgeon has created a scleral sleeve and grabs the haptic. 3) The haptic has been pulled through the sleeve; the end of the haptic can be seen sticking out. 4) A 9-0 prolene suture is passed around the haptic and through the sclera, securing the haptic in place. |

“I’m aware that this technique is controversial,” he notes. “Some surgeons have misunderstood this as being the same as leaving the haptic in the sulcus without fixation. That’s not recommended because of the potential for the haptic to cause uveitis, pigment loss and so forth. However, this approach is very different from that. In fact, I have successful five-year follow-up on a small case series in which I used this technique.

“Incidentally,” he adds, “when using this technique the fixation of the toric lens is absolute. A toric lens can rotate inside a capsular bag. That’s one of the potential issues with these lenses, although the newer designs make rotation less likely. But when you fixate the lens with a suture, the lens is locked in position—it won’t move a micron.”