Cataract surgeons take their techniques very seriously, sticking with what works and discarding what doesn’t. Over time, however, techniques change with the advent of new technology or the promise of improved results. On this year’s survey of cataract technique, surgeons delve into their preferred techniques, as well as what they’re thinking of trying in the future.

This year, 2,818 of the 10,065 surgeons receiving the survey opened it (28 percent open rate), and 99 completed the survey. To see how your approaches compare with theirs, read on.

Breaking up the Lens

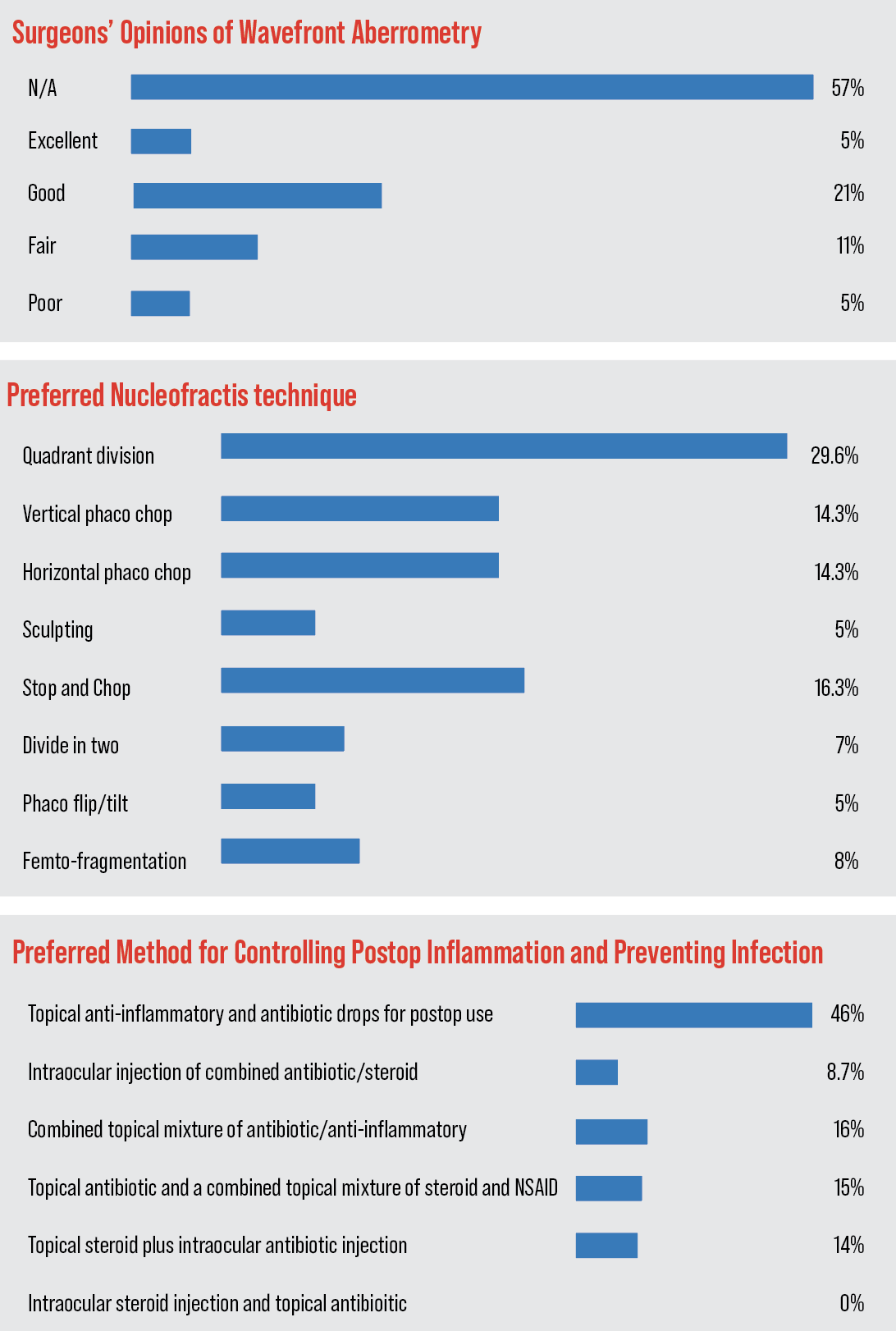

Like last year, quadrant division is still the most popular single option for nucleofractis, chosen by 29.6 percent of respondents. Some other methods are popular, as well, however.

“[Quadrant division] is simple and applies to nearly everything,” says Babak Marefat, MD, of Topeka, Kansas. “I can divide two quadrants and chop the rest with the connor wand easily. Versatile to redirect and convert.” John Willer, DO, of The Dalles, Oregon, also likes quadrant division. “It’s tried and true. Endothelial protection isn’t as important as it was in the past due to modulated ultrasound,” he says. Peter A. Rapoza, MD, says quadrant division is “widely applicable to most cataracts, fast and safe.”

Though it may be early to call it a trend, vertical chop increased from 7 percent on last year’s survey to 14 percent this year. “[With vertical chop], section size is tailored to lens density,” says one surgeon. “All activity is away from the endothelium and within the safe zone inside the CCC, and the technique is efficient and reproducible.” Chicago surgeon Robert Fantus prefers the technique because of its “decreased phaco time/energy,” and says that it’s “more efficient than grooving in certain cases.”

Another popular option selected by the surgeons on the survey is stop and chop (16 percent). “A central groove allows more working space and adds minimal time and phaco energy,” says a surgeon from Washington. “Horizontal chopping after the central groove is created is efficient with both time and phaco energy.” Sid Moore, MD, of Macon, Georgia, also prefers stop and chop. “I’m able to use it on almost any type of cataract, it’s zonule friendly, versatile, and allows for ‘open field running,’ if needed,” he says. “[Stop and chop] is more versatile and effective with less chance of corneal complications,” says an ophthalmologist from North Carolina.

The other preferred methods appear in the graph below.

|

Alternative Technologies

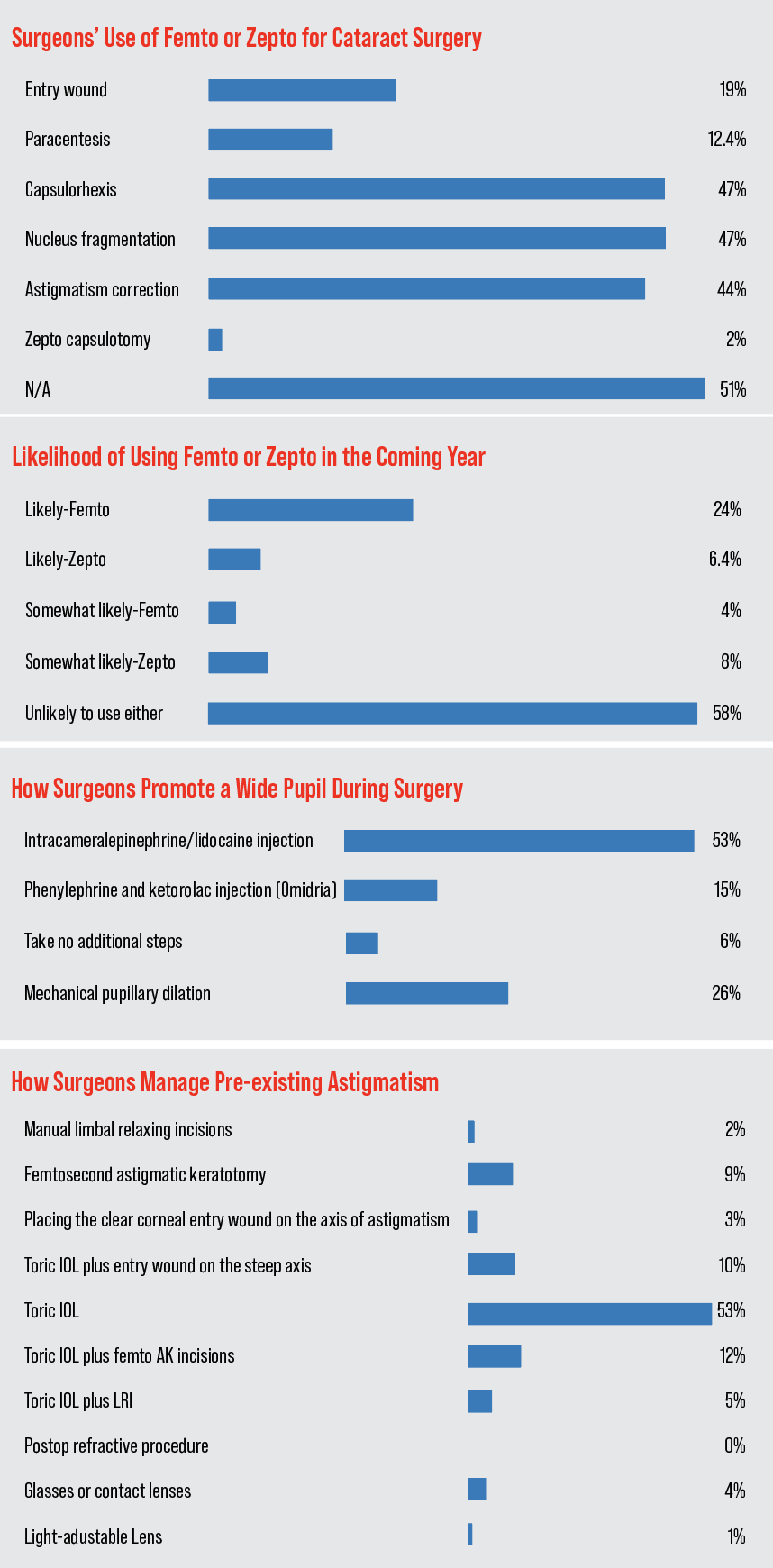

Surgeons also discussed their use of technology such as the femtosecond laser and the Zepto device. Forty-eight percent of the surgeons on the survey use one or the other for their procedures. Of the surgeons who use the devices, 98 percent use the femtosecond for some aspect of the surgery, and 2 percent use the Zepto for capsulotomy creation. In terms of what surgeons use the femto for the most, it’s a tie between the capsulorhexis and nuclear fragmentation (47 percent each), with femto astigmatic cuts coming in second (44 percent). The rest of the uses appear in the graph below.

“[The femtosecond] is safer and protects endothelium,” says Alan Aker, MD, of Boca Raton, Florida. “It helps in patients on Flomax and those with poor dilation. There’s quicker healing, and it makes perfect capsulotomies. A surgeon from New York agrees, saying, “It’s very accurate, reliable, and it makes the surgery more predictable and safe.”

Ligaya Prystowsky, MD, of Nutley, New Jersey, believes her results with the femto have trended better than if she didn’t use it. “It definitely is better for the patient in the long run over the years,” she says. “I noted slower PCO formation, though this could have been the ZCBOO [IOL], better cleanup and centration of the IOL.” She adds, however, “The expense to the patient is hard to justify when phaco alone has excellent results as well.”

On the topic of Zepto, Chicago’s Dr. Fantus thinks it can be helpful. “I think Zepto is useful in complex cases and for centering the ‘rhexis in toric cases.”

The femto skeptics, however, say they don’t see the benefit.

“It’s expensive, slower and the results aren’t demonstrably better [than manual],” says a surgeon from Washington.

“Femto is a waste of time and money. It just increases the complexity of the surgery and, if anything, is a disadvantage to a proper ‘rhexis done with manual technique,” says Steve Safran, MD, of Lawrenceville, New Jersey. “There’s nothing that it offers that I can’t do better without it. It’s a distraction and an expensive one at that! The astigmatic cuts it makes have created problems in many corneas and the nucleus fragmentation is nowhere near as efficient as what can be done with modern chopping. Pass.”

The physicians also discussed the use of intraoperative wavefront aberrometry for zeroing in on the right IOL power. Forty-two percent of the respondents say they use it in some capacity.

Only 5 percent of the users rate the technology as “excellent,” though 21 percent say it’s “good.”

The ratings appear in the graph above.

Five percent rate it as “poor.” Twenty-four percent of them say they intend to use it less in the coming year, 4 percent will use it more and 72 percent say they’ll be using the same amount of intraoperative aberrometry as last year.

Dr. Rapoza has found value in intraoperative aberrometry. “[It gives] increased accuracy in post laser vision correction and premium IOL cases, plus those with long and short axial lengths,” he says. Virginia Beach’s G. Peyton Neatrour, MD, agrees for the most part, saying, “I used it for 13 years pre Light-Adjustable Lens, which has replaced intraoperative aberrometry for post-refractive patients. I still use it for the best EDOF results.”

A majority of the surgeons continue to hang back, though.

“I’m unimpressed by the patient results that I see following intraoperative aberrometry,” says a surgeon from Colorado. “Yes, all procedures have a given failure rate, but when people pay for added precision, they should get improved precision. They shouldn’t be going elsewhere for second opinions on what went wrong.” Oregon’s Dr. Willer is also dubious, saying, “It’s way too expensive, there’s a learning curve, it takes up microscope real estate, and it’s not all that useful.”

|

When IOLs Need Support

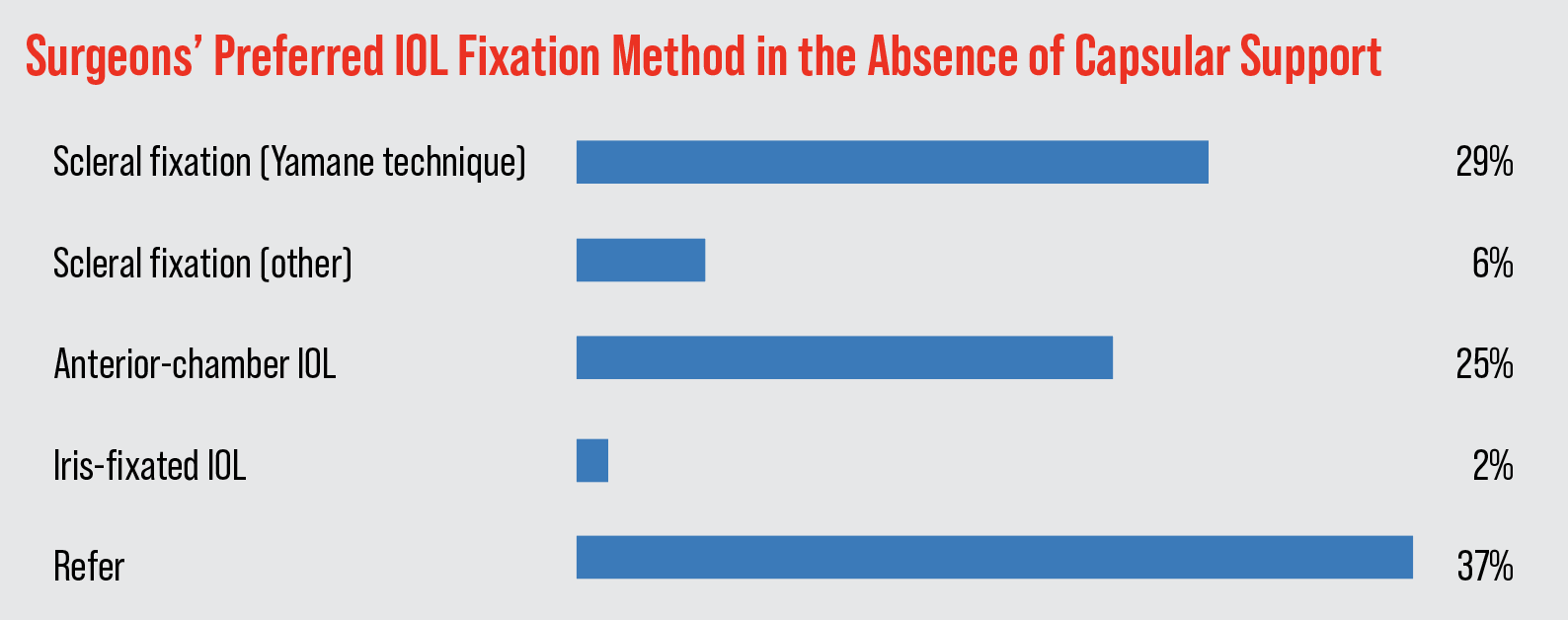

In those unfortunate cases in which there’s little or no capsular support, surgeons outlined the routes they like to take.

The most popular single option was to refer the patient (37 percent), followed by scleral fixation with the Yamane technique (29 percent) or the placement of an anterior chamber lens (25 percent). The graph of the options appears below.

|

“While [Yamane] can be technically challenging, it is effective,” says a New York surgeon. Jason Jones, MD, of Sioux City, Iowa, opines: “[The Yamane technique] is elegant and simple when executed well.” Dr. Safran agrees, saying, “[Yamane] is reliable, efficient and yields excellent outcomes.”

Proponents of anterior-chamber lens placement feel it offers other benefits. “It’s easiest,” says a surgeon from Ohio. “I’ll do Yamane but it’s more challenging and sometimes the IOL ends up tilted. An ACIOL is easy and, although some might disagree, is very well tolerated.” A physician from Washington says safety has improved with the technique. “Modern

ACIOLs give good visual outcomes and stability without the high incidence of UGH syndrome that was seen with older designs,” he says.

For surgeons who feel discretion is the better part of valor and choose to do neither technique, they say a referral can be best for a patient. “I don’t have enough volume to feel comfortable that I’m the best person to be providing this service, given the volume performed by my local peers,” says a surgeon from Colorado. Dr. Waller shares that sentiment, saying, “I haven’t performed any of the IOL fixation techniques often enough to be proficient, so I refer the patient.”

Managing Astigmatism

Similar to previous years, most surgeons (53 percent) turn to toric IOLs to manage pre-existing astigmatism.

“Toric lenses give good refractive results without having to add extra corneal incisions or modify placement into less ergonomic location,” says a surgeon from Washington. A physician from California outlines his thought process, saying, “It depends on the magnitude and the desired refractive distance result. For less than 1 D, often glasses are preferred by patients rather than a toric IOL. For large astigmatic errors, toric IOLS are preferable. As for the distance, if a patient wishes to remain myopic, then I often don’t recommend a toric IOL unless the cylinder error is greater than 2 D.”

Nine percent of respondents use femtosecond astigmatic incisions. “It’s easy and has the other advantages of FLACS,” says a surgeon from Illinois.

The rest of the options appear in the graph above.

Take-home Pearls

In addition to weighing in on specific techniques, surgeons also provided their best tips for surgical success.

“Wait one full second in foot position zero (no irrigation) before removing the phaco or I&A tip from the eye. This lowers the IOP prior to removal of the instrument. This technique decreases the chance of iris prolapse in IFIS cases,” says John C. Hart Jr., MD, of Farmington Hills, Michigan.

In a similar vein, Kathryn Hart, MD, of Greensboro, North Carolina says, “Slow down when you notice weak zonules, floppy capsule, or any other red flags. Another few minutes of operating time can keep you out of trouble.” Boston’s Dr. Rapoza says, “Optimal globe positioning allows for ease with the remaining steps.”

Dr. Fantus offers specific advice to avoid errors. “Pantomime the steps of the most common surgical procedure you do until it is muscle memory,” he says, “so that if something requires deviation from this you’re ready without throwing off your rhythm.” If you’re doing a lens exchange, Alex Hacopian, MD, of Houston suggests that you “trace the haptic with a Sinskey hook to the terminal bulb in order to free it up during IOL exchange.”

One surgeon says that experimenting with new techniques isn’t always the best idea. “Stick to the technique that works best in your hands and that you are most comfortable with,” he says. “Sometimes great is the enemy of good.”