Today, combined surgery is performed for a number of indications including epiretinal membrane, macular hole, prior complicated cataract surgery, retinal detachment, pars plana glaucoma drainage device insertion and corneal surgery. However, the logistics of combined surgery, such as sharing an OR with another surgeon and coordinating surgical schedules, can make this a daunting task. Here, I’ll share some pearls from a retina standpoint for ensuring both surgical teams are successful.

The Golden Rule

As with any type of relationship, it’s important to establish good rapport early on. The first case you do with another surgeon may be followed by many more cases in the future. Your operating room time may correspond with that of a particular retina surgeon, so it’s a good idea to get to know them and their preferences, and vice versa. Also consider what the other surgeon’s day looks like and how busy it is. Anterior segment surgeons may be quite a bit busier in terms of volume than retina surgeons, so being patient on both of our ends goes a long way. Also be sure to consider the retina surgeon’s level of experience doing combined cases. Have they done many before or is this their first time?

|

|

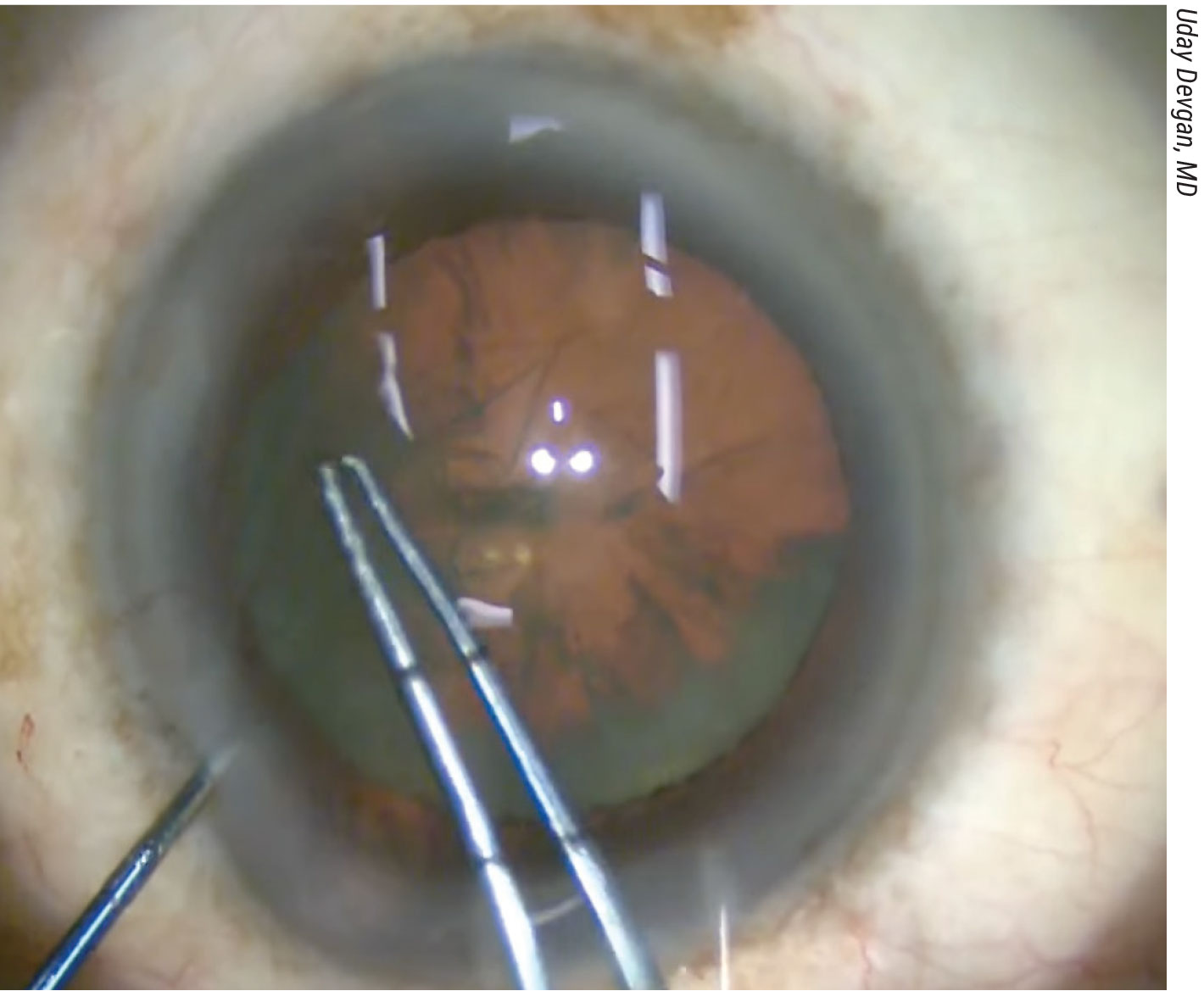

Creating a smaller capsulorhexis than usual (≤5 mm) will help to ensure that the IOL optic doesn’t prolapse during or after the case due to increased posterior pressure from an air or gas bubble. |

Order of Operations

Communicating clearly about surgical steps and comfort level with varying conditions in combined cases will help ensure that the procedures go smoothly. Here are three common combined surgery scenarios that benefit from discussion beforehand:

• Silicone oil removal. From the retina point of view, there’s not always a need to remove the silicone oil. However, relatively few anterior segment surgeons are comfortable with having silicone oil in the eye because of the potential migration of the oil to the anterior segment, which could disrupt visualization. The retina surgeon can remove the oil first to make the anterior segment surgery easier.

On the other hand, some surgeons are comfortable with keeping the silicone oil in while they perform phacoemulsification. If that’s the case, be sure to discuss how to proceed. Oftentimes, irrigation pressure from the anterior handpiece is increased in these cases to maintain stable fluidics to counter the increased posterior pressure.

• Trocar placement. Before surgery, be sure to communicate about preferences on trocar placement, position and infusion status. Do you prefer no trocar, or do you prefer to control the infusion? It’s important to note that during combined surgery, the intraocular pressure status isn’t apparent, and there are always risks for hypotony and choroidals. I prefer to pre-place an infusion trocar, whether or not a cannula is inserted. The infusion might not be turned on, per the anterior segment surgeon’s preference, in order to not apply additional posterior pressure from pars plana infusion.

• Scleral buckling. Scleral buckling will raise the posterior pressure. If done first, the anterior segment surgeon will need to keep in mind that the posterior pressure has increased.

|

|

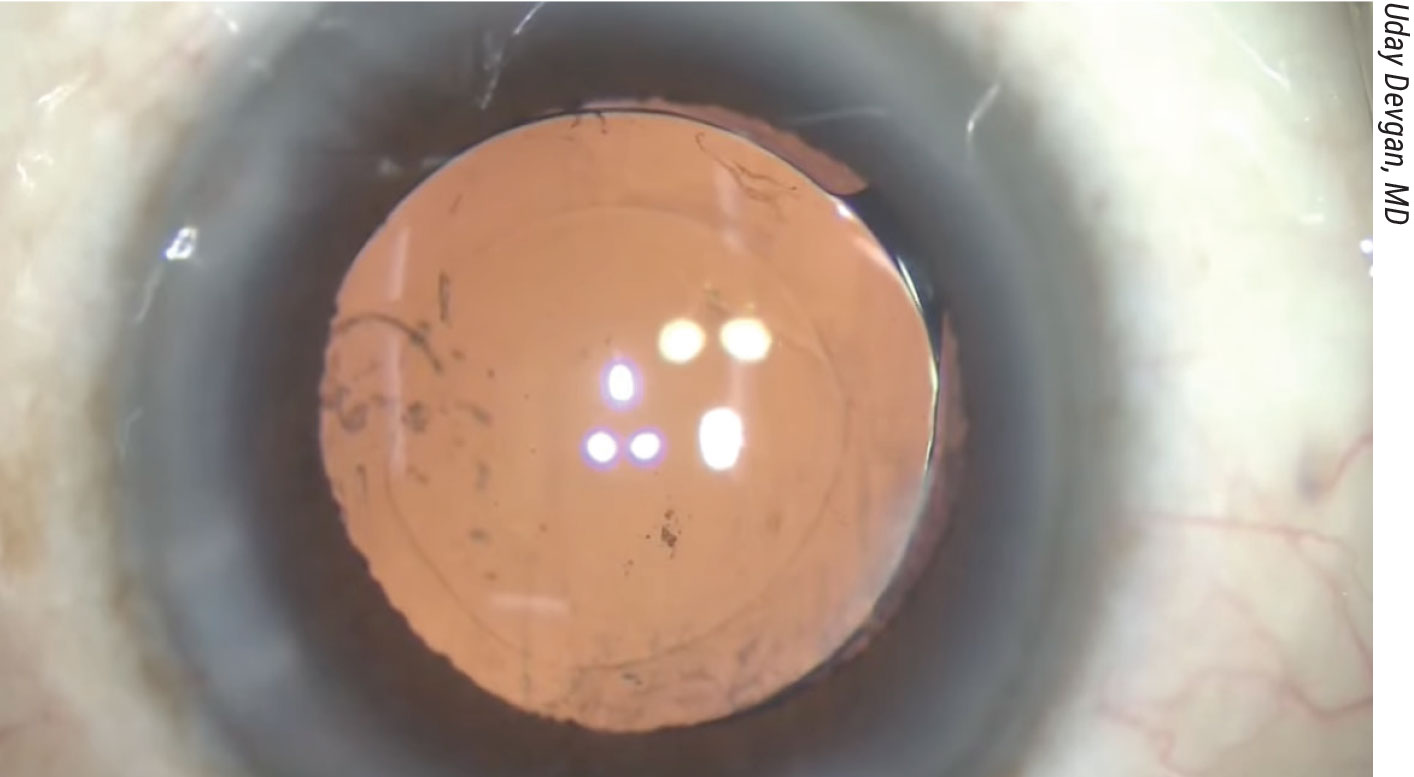

A 4.5-mm capsulorhexis with an acrylic monofocal IOL. Acrylic IOLs are preferable to silicone IOLs in combined surgery cases. |

Strategic Pearls

Here are some pearls to consider for one of the most common combined procedures, phacovitrectomy:

• Use what’s comfortable. When performing a combined phacovitrectomy procedure, it’s often advantageous for the cataract surgeon to perform the procedure using the machine they feel most comfortable with. I’ve found that this tends to be more efficient. Having this discussion prior to the surgery is key.

• Adapt the size of the capsulorhexis. A slightly undersized capsulorhexis (≤5 mm) will help to reduce the risk of IOL optic prolapse during or after the case.

• Avoid stromal hydration. Combined cases, especially the second part done by the retina surgeon, may take a while, especially for patients with conditions such as tractional retinal detachments. Having plenty of corneal clarity and avoiding stromal hydration during I/A is key.

• Be aware of PC laxity. Oftentimes after combined surgery, the bag may be distended. Though uncommon, the retina surgeon may bite the bag during anterior vitrectomy. At the end of the surgery, there may be a small capsulotomy. Usually this isn’t an issue provided the rest of the cataract surgery goes well but be aware that the Viscoat or ProVisc may create a laxness of the PC and increase the risk for that.

• Discuss the preferred type of wound closure. Some retina surgeons prefer suture closure of the main wound.

• Assess IOL position and AC morphology. At the end of the case, because of the fluidics, the optic may peak out of the pupil a bit or there may be some anterior chamber shallowing. Sometimes the retina surgeon may bring the anterior segment surgeon back in. Or, if the retina surgeon feels comfortable, then they may help by putting more fluid into the anterior chamber, changing the infusion pressure and/or putting in some Miochol to constrict the iris to prevent IOL prolapse anteriorly.

• Assess the retina. Be sure to perform scleral indentation and look at the peripheral retina to assess for any retinal breaks.

• Communicate postoperative positioning. Early postoperative positioning may be required in cases requiring tamponade for retinal breaks.

•Hold off on cycloplegia. Miotics often aren’t needed unless there’s evidence of significant IOL prolapse. In these cases, try to avoid cycloplegia until postop day one or later.

In summary, when performing combined surgery, it’s important to know your partner, conduct a thorough pre-planning discussion and communicate clearly with each other. Phacovitrectomy can be executed safely using single-piece IOLs with appropriate modifications to microsurgical technique: wound construction; small capsulorhexis; and avoiding stromal hydration.

Dr. Rao is the Leonard G. Miller Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and an associate professor of ophthalmology, pathology and human genetics at the University of Michigan. He has no related financial disclosures.