Presentation

A 63-year-old Caucasian male with one week of pain, redness and decreased vision in the left eye initially presented for ophthalmic evaluation with his local ophthalmologist. On examination, he was determined to have a bacterial keratitis with corneal cultures taken and was started on hourly fortified cefazolin and tobramycin topical drops. A thorough ocular/medical history at the time was only remarkable for nocturnal lagophthalmos; the patient denied any soft contact lens use or recent ocular trauma. Culture data at follow-up resulted in pan-sensitive Pseudomonas and the patient was transitioned to hourly fortified tobramycin and moxifloxacin drops. Despite culture-guided therapy, the patient continued to develop worsening pain, leading to presentation to the Wills Eye emergency room.

History

Prior ocular history is notable for cataract extraction with intraocular lens placement in both eyes. Past medical history is significant for asthma, hyperlipidemia and Goodpasture syndrome status post failed kidney transplantation now with end-stage renal disease requiring peritoneal dialysis. His family history was noncontributory. He denies any current or previous tobacco or recreational drug use and reports only occasional alcohol intake.

Current medications included oral prednisone 2.5 mg daily, calcium acetate three times per day with meals, Symbicort/albuterol inhalers, Aspirin 81 mg once daily and atorvastatin 40 mg daily.

|

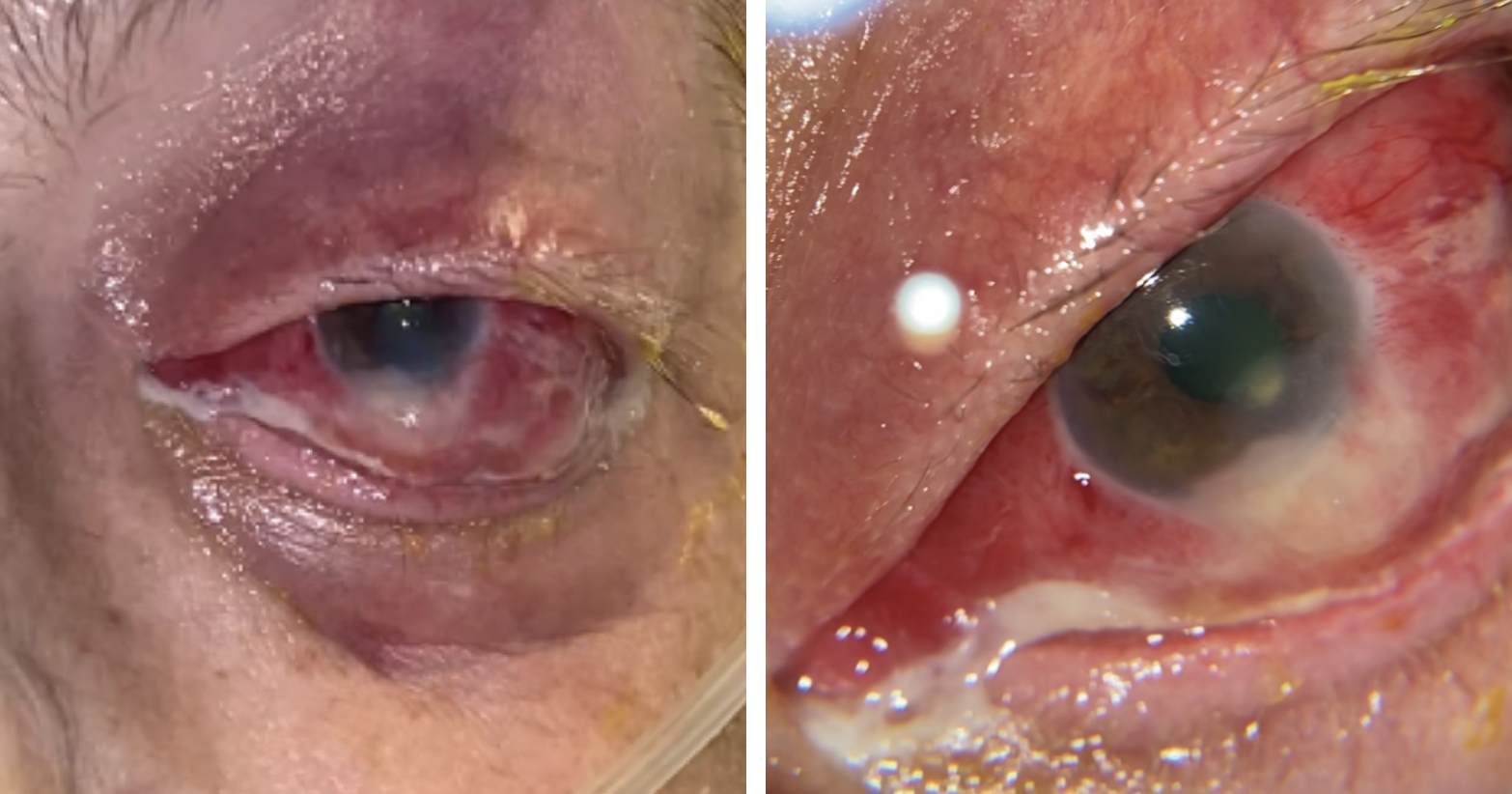

| Figure 1 A and B. External photographs of the left eye at initial time of presentation demonstrating severe scleral injection, suppurative discharge and a focal whitening of the inferior perilimbal sclera with thinning and adjacent scleral abscess. |

Examination

The patient’s vital signs were stable. He was afebrile. Ocular examination demonstrated best corrected near visual acuity of 20/20 OD and Hand Motion OS. Intraocular pressure by Tonopen was 16 and 12 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Pupillary exam demonstrated an irregular pupil shape of the left eye though without an afferent pupillary defect. External exam of left eye revealed pronounced periorbital erythema, soft tissue edema and mildly restricted ocular movements (Figure 1). The anterior segment was notable for severe diffuse scleral injection, suppurative discharge and a 3 x 3-mm focal whitening of the inferior perilimbal sclera with thinning and adjacent scleral abscess at 6 o’clock. A dense white corneal infiltrate with overlying sliver epithelial defect inferiorly was noted; the rest of the cornea showed moderate stromal edema. There was a concurrent 1.5-mm, non-mobile hypopyon and a centered posterior chamber intraocular lens. Dilated fundus exam was limited secondary to media opacity. The anterior and posterior segment examination of the right eye was unremarkable except for a well-positioned PCIOL. B-scan ultrasonography of the left eye revealed moderate anterior vitreous opacities layering inferiorly, underlying inferior scleral abscess and mild posterior scleral thinning. CT orbits with contrast noted left orbital wall thickening with surrounding fatty infiltration and accompanying preseptal inflammation without post-septal extension.

What’s your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

The differential diagnosis for this patient presenting with acute onset scleritis includes infectious and inflammatory etiologies. Infectious causes include bacterial (Pseudomonas spp, Staphylococcus spp, Streptocococcus spp, and tuberculosis), fungal, protozoan and viral (VZV and HZV). Inflammatory etiologies may be idiopathic or associated with an underlying rheumatologic history. Given the patient’s clinical history, particularly a preceding culture-positive bacterial keratitis, the highest consideration was placed on infectious sources.

A repeat corneal scraping and culture of the suppurative discharge was performed, and the patient was started on fortified vancomycin/tobramycin hourly, ciprofloxacin drops hourly, atropine b.i.d. and intravenous ciprofloxacin. Subconjunctival tobramycin was administered, and the patient underwent scleral deroofing in the operating room the next day with additional cultures taken. Bacterial cultures revealed heavy-growth, pan-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The patient was continued on topical ciprofloxacin and fortified tobramycin drops hourly, ciprofloxacin ointment every four hours (q4h), atropine b.i.d. and systemic IV ciprofloxacin with close daily observation. He additionally received daily subconjunctival tobramycin until ultimately requiring further surgical debridement. On day seven, he underwent sclerectomy and abscess drainage with amniotic membrane scleral patch graft with an intravenous angiocatheter insertion, conjunctivoplasty and punctal occlusion of the left eye. Subsequently, a tobramycin infusion (40 mg/mL) twice daily was administered through the intraoperatively inserted subconjunctival catheter for two days (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2 A and B. External photographs of the left eye postoperatively, demonstrating amniotic membrane scleral patch graft with intravenous angiocatheter insertion (A) and subsequent dressing to allow for continuous tobramycin infusions (B). |

On evaluation on Day 10 from initial presentation, the visual acuity in the left eye had improved from hand motion to 20/200 with notable improvement of scleral injection, discharge and intraocular inflammation. At this point, the catheter was removed and a temporary tarsorrhaphy was placed; topical therapy was continued with ciprofloxacin and tobramycin ointment q4hr, atropine b.i.d. and topical prednisolone acetate q.i.d. along with oral ciprofloxacin. The patient was eventually discharged with plan for close follow-up in the outpatient cornea clinic.

Discussion

Infectious scleritis is a rare, severe ocular disorder that’s often associated with poor prognosis due to its diagnostic challenge and delay in treatment. Characterized by deep inflammation of the sclera, scleritis most commonly occurs secondary to immune-mediated inflammation, though about 5 to 15 percent of all cases are due to infectious etiologies.1 Inappropriate recognition of IS may lead to use of immunosuppressive therapy, risking exacerbation of active infectious process. Thus, a thorough patient history and evaluation for infectious processes should be considered in cases of severe monocular presentations.

IS can be classified as primary and secondary etiologies––the former occurs as a consequence of preceding scleral surgery or trauma, while the latter typically refers to extension of disease from a primary infection, such as a keratitis as suspected in our case. Preceding ocular surgery is the most common risk factor, particularly pterygium excision, though other cited surgical associations include cataract extraction, vitreoretinal surgery, strabismus surgery and glaucoma filtration surgery.2 Additional risk factors of IS include trauma, local (ocular) or systemic immunosuppressive agents, radiation therapy, iatrogenic sources (subtenon or intravitreal injections) and immunocompromising disorders (HIV infection, diabetes mellitus).2,3 Bacterial sources account for the majority of cases with Pseudomonas spp being the most common (up to 85 percent).4 Gram-positive bacteria, specifically Staphylococcus spp and Streptococcus spp, are also frequently associated, particularly following invasive ocular procedures.5,6 Additional microbial sources have been implicated, especially in the setting of various environmental factors/exposures, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis in endemic regions (e.g., India) and fungi in developing countries and tropical climates.2 While much rarer, other sources cited in current literature include spirochetes (e.g., Lyme disease, often with concurrent neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations), protozoa (e.g., Toxoplasma gondii-associated posterior scleritis with chorioretinitis, panuveitis), helminths (e.g., toxocariasis) and viruses (Herpesviridae family).1,2,6

Early recognition and culture-guided antimicrobial therapy are the mainstays of treatment for IS; delayed diagnosis can lead to visually devastating complications including endophthalmitis, perforation and dissemination. Prompt initiation of topical antimicrobial therapy as well as concurrent systemic agents has been associated with improved prognosis; additional prolonged therapy duration even beyond clinical improvement has been associated with better outcomes for IS.6,8 Despite appropriate initiation of antimicrobials, medical therapy alone is often insufficient for true source control due to scleral avascularity, dense collagen fiber networks and prohibitive biofilms. In fact, up to 80 percent of cases of IS require surgical intervention including surgical debridement, patch graft placement, conjunctival flap, tenonplasty and tarsorrhaphy.2 In a 10-year consecutive case series of culture-positive Pseudomonas scleritis, the authors reinforced that surgical intervention not only aids in confirming diagnosis but also allows for therapeutically reducing microbial load.9 Additionally, the use of subconjunctival antibiotics in conjunction with surgical therapy has been associated with improved outcomes.9,10 However, frequent subconjunctival administration of therapy with injections carries many disadvantages.

Recognition of this challenge prompted the development of the suprapalpebral lavage, first described in 1966.11 SPL was originally derived from veterinary medicine allowing for continuous local delivery of antimicrobial therapy and, to date, the technique has undergone many modifications to allow for maximized antibiotic delivery while minimizing surgical complications (e.g., ptosis).12,13 One report described a case series of six patients with IS and keratitis refractory to topical antibiotic therapy that improved with SPL, citing the ability to reduce bacterial load on the ocular surface and improved antibiotic penetration.14 In our case, we used a novel variant of a SPL by directly placing an intravenous angiocatheter underneath the amniotic membrane scleral patch graft to allow for twice daily antibiotic infusion. To our knowledge, this is the first case report detailing such an approach and ultimately resulting in a favorable outcome.

In conclusion, IS is a serious ocular disorder associated with poor prognosis, particularly in the setting of delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. Successful treatment is dependent on aggressive, culture-guided antimicrobial therapy, often in conjunction with surgical management. While inspiration from veterinary medicine has allowed for breakthrough in treatment of severe cases, ongoing exploration of therapeutic approaches may prove invaluable in managing this challenging and vision-threatening disease.

1. Jabs DA, Mudun A, Dunn JP, et al. Episcleritis and scleritis: Clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:469-476.

2. Yu J, Syed ZA, Rapuano CJ. Infectious scleritis: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Eye Contact Lens 2021;47:8:434-441.

3. Reynolds MG, Alfonso E. Treatment of infectious scleritis and keratoscleritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112:543–547.

4. Meyer JJ, Espandar L, Marx DP, et al. Pseudomonas scleritis resistant to fourth-generation fluoroquinolones in a patient without prior trauma or surgery. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2008;16:127–129.

5. Jain V, Garg P, Sharma S. Microbial scleritis-experience from a developing country. Eye 2009;23:255–261.

6. Reddy JC, Murthy SI, Reddy AK, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of bacterial and fungal scleritis at a tertiary eye care hospital. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2015;22:203–211.

7. Lane J, Nyugen E, Morrison J, et al. Clinical features of scleritis across the Asia-Pacific region. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019;27:920–926.

8. Moreno Honrado M, del Campo Z, Buil JA. A case of necrotizing scleritis resulting from Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cornea 2009;28:1065–1066.

9. Ahmad S, Lopez M, Attala M, et al. Interventions and outcomes in patients with infectious Pseudomonas scleritis: A 10-year perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019;27:499–506.

10. Syed ZA, Rapuano CJ. Umbilical amnion and amniotic membrane trans- plantation for infectious scleritis and scleral melt: A case series. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2021;21:101013.

11. Hessburg PC. Treatment of pseudomonas keratitis in humans. Am J Ophthalmol 1966;61:896–903.

12. Yang LY, Huang JJM, Toohey TP, et al. Subpalpebral antibiotic lavage as safe, emergent, and cost-effective management of acute infectious keratitis related to contact lens overwear: Case report and literature review. Cornea 2022;41:249–251.

13. Maeng, MM, Casella, A, Herrera, G, et al. Subpalpebral antibiotic lavage for the treatment of refractory infectious scleritis. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2023;39:2:e55-e58.

14. Meallet MA. Subpalpebral lavage antibiotic treatment for severe infectious scleritis and keratitis. Cornea 2006;25:159–163.