The differential diagnosis of retinal or choroidal infiltrative lesions is broad and includes infectious, inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. The most important are listed below:

• Infectious

– acute retinal necrosis

– fungal endophthalmitis

– bacterial endophthalmitis

– syphilis

– toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis

– tuberculosis

• Inflammatory

– sarcoidosis

– acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment

• Epitheliopathy

– multifocal choroiditis

– serpiginous choroidopathy

– idiopathic posterior uveitis

– autoimmune choroidopathy

– CTLA4 choroidopathy

• Neoplastic

– vitreoretinal lymphoma

– uveal lymphoma

– uveal metastasis

|

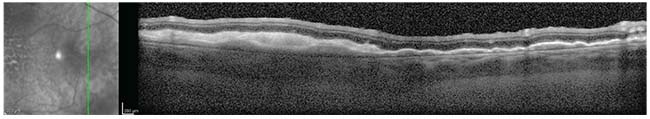

| Figure 2. OCT of the temporal macula demonstrating an undulating configuration of hyper-reflective sub-RPE deposits below an intact retina. |

Diagnosis and Workup

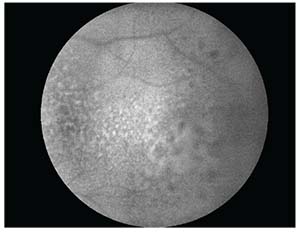

Given the patient’s age and presentation, vitreoretinal lymphoma was at the top of the differential diagnosis. Diagnostic testing using optical coherence topography revealed undulating, hyper-reflective sub-RPE deposits below an intact retina (See Figure 2). Fundus autofluorescence demonstrated mottled hyperautofluorescent RPE in the macular region at the site of the sub-RPE lesions. (See Figure 3) Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits revealed thickening and layering of material in the posterior aspect of the left eye, but otherwise normal orbits. A lumbar puncture was performed and cerebrospinal fluid studies were within normal limits. Cytology did not demonstrate abnormal lymphocytes.

The patient subsequently underwent fine needle aspiration biopsy of the sub-RPE deposits. Cytopathological examination revealed a few small, well-differentiated lymphocytes not typical of lymphoma, but consistent with a diagnosis of chronic vitreous inflammation. Knowing that multiple biopsies are often required to demonstrate positive pathology for ocular lymphoma,1 a vitreous

|

| Figure 3. Fundus autofluorescence of the temporal macula demonstrating mottled hyperautofluorescence in the region of the lesion. |

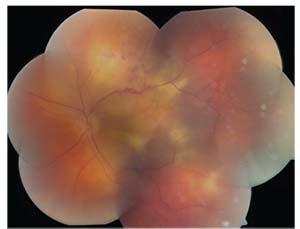

After two negative biopsies for lymphoma, it was decided to treat the patient for presumed autoimmune uveitis. The patient received 40 mg of sub-Tenon’s fascia Kenalog. Nine days after the administration of STK, repeat fundoscopic examination revealed rapid enlargement and coalescence of the creamy yellow sub-RPE lesions, in addition to intraretinal hemorrhage along the superior arcade (See Figure 4). Concern for persistent tumor, rather than inflammation, was raised, despite the negative biopsies.

Rapid expansion of the lesions following injection of STK was also concerning for possible infectious etiologies and the differential diagnosis was refocused to include HIV ELISA, ANCA, CBC, CMP, ESR, RPR, FTA-ABS, quantiferon gold, toxoplasmosis and bartonella titers. An anterior chamber tap was performed and aqueous was sent for PCR testing to assess for toxoplasmosis, CMV, VZV and HSV. The patient subsequently underwent a second PPV, diagnostic retinectomy and drainage of the subretinal fluid. The SRF was sent for fungal and bacterial stain, culture and PCR analysis.

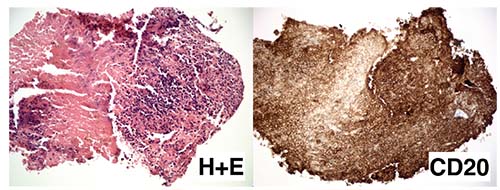

The previous serological workup and PCR results didn’t identify a specific etiology. Fungal, Gram stain and AFB stain were negative for microorganisms. Fungal and bacterial cultures showed no growth. Pathological examination of the retinal biopsy demonstrated a segment of extensively necrotic retina diffusely infiltrated with small lymphocytes (See Figure 5). Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse positive reactivity for B-cell marker CD20 (See Figure 5), consistent with a diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma. The patient was diagnosed with bilateral primary vitreoretinal lymphoma without central nervous system involvement.

Treatment

The patient was treated with bilateral intravitreal methotrexate injections. After the twelfth injection OD and the sixth OS he had resolution of the floaters and vitreous cells OU, and involution of the sub-RPE lesions OS. His vision after the final treatment was 20/20 OD and hand motion OS.

Discussion

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma is a subtype of intraocular lymphoma that includes primary CNS lymphoma with vitreoretinal involvement, termed primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. PVRL is a variant of PCNSL that originates in the eye and demonstrates extension to the CNS.2 Most patients with PVRL present symptomatically, most commonly with blurred vision (71 to 86 percent) or floaters (25 to 43 percent).3,4 However, up to 17 percent are completely asymptomatic at the time of presentation.4 Clinically, 64 to 80 percent of patients have bilateral involvement at the time of presentation.3,4

By

|

| Figure 4. The left eye demonstrated rapid enlargement and coalescence of creamy yellow sub-RPE lesions, in addition to intraretinal hemorrhage along the superior arcade after administration of STK. |

Ancillary testing of PVRL is important to guide the diagnostic evaluation, but pathology is required to make a definitive diagnosis. OCT imaging demonstrates a multifocal, dome-shaped elevation of the RPE from sub-RPE tumor deposits, retinal elevation or thickening from direct tumor infiltration, and cystoid macular edema from the associated inflammatory reaction.6 Fluorescein angiography often shows clusters of round hyper- or hypofluorescent lesions, in both the early and late phases, along with heterogenous choroidal fluorescence.5 Fundus autofluorescence demonstrates multiple weak or strong hyperautofluorescent spots, suggesting overlapping of PVRL and RPE cells, and hypoautofluorescent areas that suggest PVRL cells above the RPE, or RPE atrophy.5

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy or pars plana vitrectomy with cytopathologic diagnosis remains the mainstay of diagnosis of this condition. In questionable cases, Myd88 mutation testing can guide the diagnosis of PVRL and is positive in 83 percent of cases.7 Measurement of IL-6 and IL-10 in aqueous or vitreous fluid can raise the suspicion for PVRL, but an elevated IL-10/IL-6 isn’t diagnostic.8

Cytopathological features can be varied in PVRL. PVRL cells are large, atypical lymphoid cells with large, irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli and scant basophilic cytoplasm. These cells are prone to spontaneous necrosis, which may contribute to the high false-negative rate of pathologic diagnosis, so careful and prompt processing is critical.9 One study documented that multiple vitreous biopsies are often required to demonstrate adequate pathology in PVRL, requiring three vitreous biopsies in some cases.1 MRI of the brain and LP should be performed in all individuals suspicious for PVRL to assess for CNS involvement.5 The findings of CNS lesions on MRI or lymphoma cells in the CSF support the diagnosis of PVRL and can negate the need for ocular biopsy.5

There’s no consensus defining the single best therapy for PVRL. Treatment options include intravitreal methotrexate or rituximab, and external beam radiation therapy (EBRT).10-12 The largest reported series of patients treated with intravitreal methotrexate included 44 eyes in 26 patients using an induction-consolidation-maintenance regimen.10 All cases achieved clinical remission after an average of 6.4 injections with 95 percent of eyes responding to 13 injections or less.10 None of the patients treated with intravitreal methotrexate relapsed during a follow-up period ranging from 41 to 107 months.10

Both animal and human studies suggest that intravitreal rituximab may require fewer injections (median: four) and have fewer side effects than

|

| Figure 5. Hemotoxalin and eosin preparation (low power, left) of the retinal biopsy demonstrating extensively necrotic retina diffusely infiltrated by small lymphocytes with uniform positive reactivity to the B-cell marker CD20 (right). |

The treatment for PVRL with CNS spread is similar to that for PCNSL with or without vitreous involvement, with systemic intravenous methotrexate the most commonly used agent.13 A large, multicenter, retrospective study found that the median progression-free and overall survival was 18 and 31 months, respectively.13

The prognosis of PVRL is unfortunately bleak, with 65 to 90 percent of patients going on to develop CNS lymphoma during their lifetime.5 In a large multicenter study, of 60 patients diagnosed with PVRL with a negative MRI done at the time of diagnosis, 15 percent were found to have positive CSF cytology, indicating subclinical involvement of the CNS at the time of diagnosis.2 The study’s authors went on to note that of 83 patients initially diagnosed with and treated for localized PVRL, 56 percent relapsed and 62 percent went on to have CNS involvement by 19 months.2 Median progression-free time and overall survival were 30 and 58 months, respectively, and were unaffected by treatment type.2 Regardless of which therapy is used, there’s a very high likelihood of local recurrence and CNS involvement, justifying the need for periodic CNS monitoring with MRI.

Although there is a high likelihood for PRVL to progress to CNS disease, a 17-center European study showed there was no significant difference in the development of CNS lymphoma between patients treated with local chemotherapy or radiotherapy versus prophylactic systemic therapy.14 CNS involvement occurred in 32 to 43 percent (median time of occurrence: 49 months) and wasn’t statistically different between the treatment groups.14

In summary, a 60-year-old man presented with bilateral floaters, vitritis and rapidly progressing retinal lesions of the left eye. Two biopsies demonstrated chronic inflammation. A third biopsy of the retina and vitreous revealed a diagnosis of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. The patient was successfully treated with intravitreal methotrexate to remission. He’ll be monitored for recurrence and involvement of the central nervous system. REVIEW

1. Char DH, Ljung BM, Deschênes JE, Miller TR. Intraocular lymphoma: Immunological and cytological analysis. Brit J Ophthalmol 1988;72:12:905-911.

2. Grimm SA, Pulido JS, Jahnke K, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma: An international primary central nervous system lymphoma collaborative group report. Ann Oncol 2007;18:11:1851-55.

3. Hoffman PM, McKelvie P, Hall AJ, et al. Intraocular lymphoma: A series of 14 patients with clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Eye 2003;17:4:513-521.

4. Peterson K, Gordon KB, Heinemann MH, DeAngelis LM. The clinical spectrum of ocular lymphoma. Cancer 1993;72:3:843-849.

5. Chan CC, Rubenstein JL, Coupland SE, et al. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A report from an international primary central nervous system lymphoma collaborative group symposium. The Oncologist 2011;16:11:1589-99.

6. Say EA, Shah SU, Ferenczy S, Shields CL. Optical coherence tomography of retinal and choroidal tumors. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;385058:Epub 2011 Jul 18.

7. Raja H, Salomão DR, Viswanatha DS, Pulido JS. Prevalence of MYD88 L265P mutation in histologically proven, diffuse large B-cell vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retina 2016;36:3:624-628.

8. Akpek EK, Maca SM, Christen WG, Foster CS. Elevated vitreous interleukin-10 level is not diagnostic of intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma. Ophthalmology 1999;106:12:2291-2295.

9. Char DH, Ljung BM, Deschênes JE, Miller TR. Intraocular lymphoma: Immunological and cytological analysis. Brit J Ophthalmol 1988;72:12:905-911.

10. Frenkel S, Hendler K, Siegal T, et al. Intravitreal methotrexate for treating vitreoretinal lymphoma: 10 years of experience. Brit J Ophthalmol 2008;92:3:383-388.

11. Kitzmann AS, Pulido JS, Mohney BG, et al. Intraocular use of rituximab. Eye 2007;21:12:1524-1527.

12. Berenbom A, Davila RM, Lin HS, Harbour JW. Treatment outcomes for primary intraocular lymphoma: Implications for external beam radiotherapy. Eye 2007;21:9:1198-1201.

13. Grimm SA, McCannel CA, Omuro AM, et al. Primary CNS lymphoma with intraocular involvement International PCNSL Collaborative Group Report. Neurology 2008;71:17:1355-1360.

14. Riemens A, Bromberg J, Touitou V, et al. Treatment strategies in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A 17-center European collaborative study. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:2:191-197.