Holding safety paramount to efficacy is the overarching principle for determining whether a patient is a candidate for corneal-based refractive surgery, according to Gaurav Prakash, MD, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “You will have some patients who are borderline, and you may have to say ‘no’ or offer something else,” he says. “That said, if I randomly see 100 patients, about 60 to 70 percent will probably fit into some sort of refractive surgery, corneal-based or otherwise.”

Here, veteran surgeons discuss the steps they take and the red flags they look for when evaluating prospective corneal refractive surgery patients.

Communicating Expectations

“Giving patients very realistic expectations early on is important,” says Dr. Prakash. “I always tell patients that the aim is to make them less dependent on glasses, but that might mean they still need glasses for challenging tasks, and they’ll eventually need glasses for reading as they grow older. If the patient tells me they definitely want to be free of glasses, then refractive surgery and especially corneal refractive surgery is probably not for them. There’s always an amount of variation in outcome that we have to be mindful of.

“Additionally, I mention that healing can vary from person to person,” he adds. “There are risks with corneal refractive surgery as well as certain side effects. Patients should expect some amount of dryness, for which we give them drops, and may have some halos and glare in the night when driving. LASIK flap dislocation is a potential risk.”

Helen K. Wu, MD, of the New England Eye Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, notes that setting patient expectations further down the line is also important. She educates patients about cataract formation and about the eventual need for cataract surgery. “I tell them what to expect over years’ time, so they understand that laser vision correction doesn’t induce early cataracts. I also mention that laser vision correction changes the shape of the cornea, necessitating alternative methods of calculating lens implant power for cataract surgery to get the best refractive outcome.”

|

|

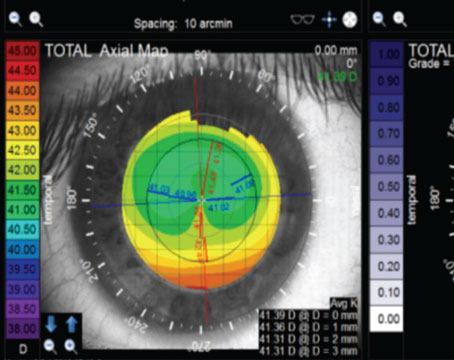

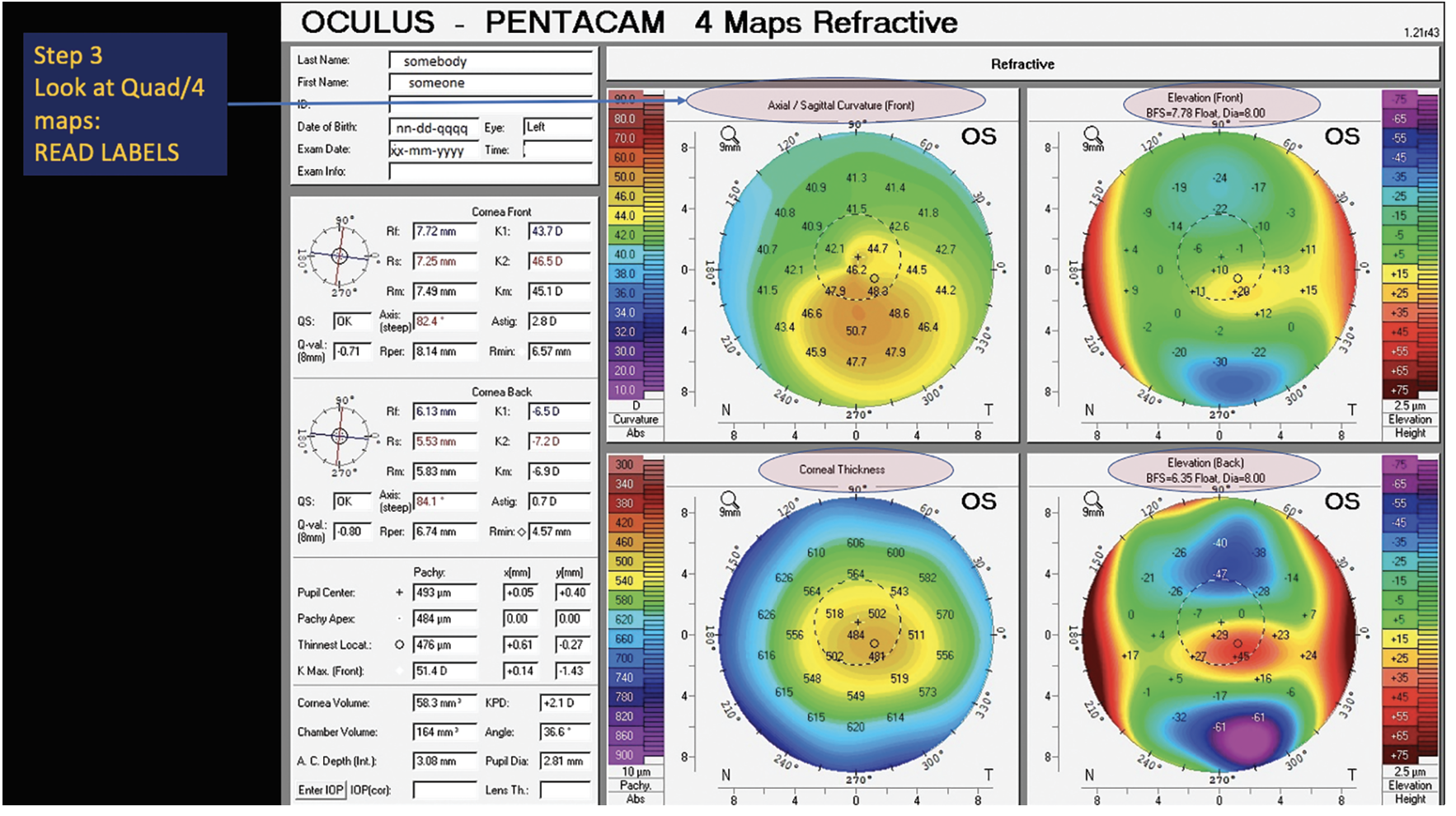

Figure 1. With the high number of scans clinicians look at every day, it’s important to double check that the topography matches the right patient in the EMR. In the upper left corner, review key demographics, including the patient’s name, date of birth, date of exam and eye. |

Ascertaining Visual Goals

Part of the screening process involves trying to understand what the patient’s goals are and how to meet those goals. The first thing Dr. Wu asks patients is why they want to have LASIK done. “Occasionally, these goals stem from vocational requirements. However, certain professions, like first responders such as firefighters, face scenarios where LASIK flaps might not be ideal—entering smoke-filled buildings, for instance. Similarly, individuals in the military or involved in contact sports are susceptible to facial impact, making them less suitable candidates for LASIK.”

Correcting both eyes for distance is a common strategy for young patients in their 20s, but this approach might not meet the visual goals of some older patients, says Dr. Wu. “When we see patients in their 40s, I don’t automatically correct both eyes for distance,” she says. “Their aim may be to eliminate the need for glasses entirely, but given their age, they’ll soon require reading glasses as natural accommodation diminishes. It’s crucial for them to comprehend this. I prefer to present blended vision as an alternative.”

A trial with disposable contact lenses can help determine candidacy for blended vision (monovision). “I work side-by-side with my optometry colleague when I’m seeing refractive surgery consultations,” Dr. Wu says. “She might provide trial lenses to achieve plano in their dominant eye and, for example, -1 D, -1.25 D, or -1.5 D in their non-dominant eye, depending on their age. Then we assess their tolerance to this setup.”

She says that while a five-day trial is often done, it may take more time than that to get completely used to blended vision. “If they tell me they’re happy with it right away, that’s a good sign,” she says. “If patients experience difficulty adapting, we can assist by allowing them to wear their contacts for a bit longer to see if their brain adjusts. It’s important to convey to highly motivated patients seeking freedom from glasses that complete elimination of glasses for reading fine print or in dim lighting may not be achievable.”

Sometimes holding off on surgery is the best option. Young patients in their mid-20s interested in LASIK may need counseling about the potential for a myopic shift, especially if they’re going to graduate school. “We call it graduate school myopia, or medical/law school myopia,” Dr. Wu says. “Patients may experience a myopic shift after LASIK due to extensive reading or screen usage, or simply because they’re in their mid-20s. If this isn’t acceptable to them, they may opt to continue wearing contact lenses until they’ve completed graduate school and then reconsider. Over the years, I’ve observed patients, perhaps initially at -2 D, undergo treatment in their early 20s, only to return to -1 D after graduate school. This could be attributed to a normal myopic shift for them, but it’s not uncommon. Refractive stability in your early 20s may vary depending on your activities.”

Dr. Prakash notes that the candidacy criteria for SMILE is similar to that of LASIK. “Any patient who isn’t a good candidate for LASIK won’t be a good candidate for SMILE,” he says. “This new procedure might offer some advantages [over LASIK] because it doesn’t have a flap, but it’s not at the same point we’re at with LASIK right now. Down the line, it might be a good treatment to consider but it’s still a bit far away from the accuracy of treatment we’re getting with LASIK.”

|

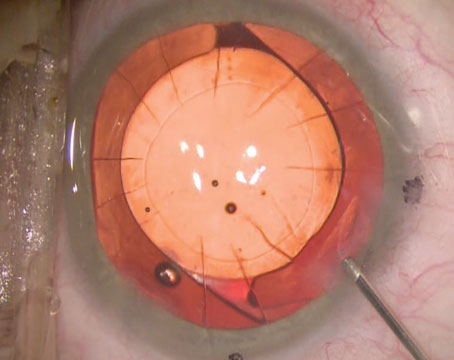

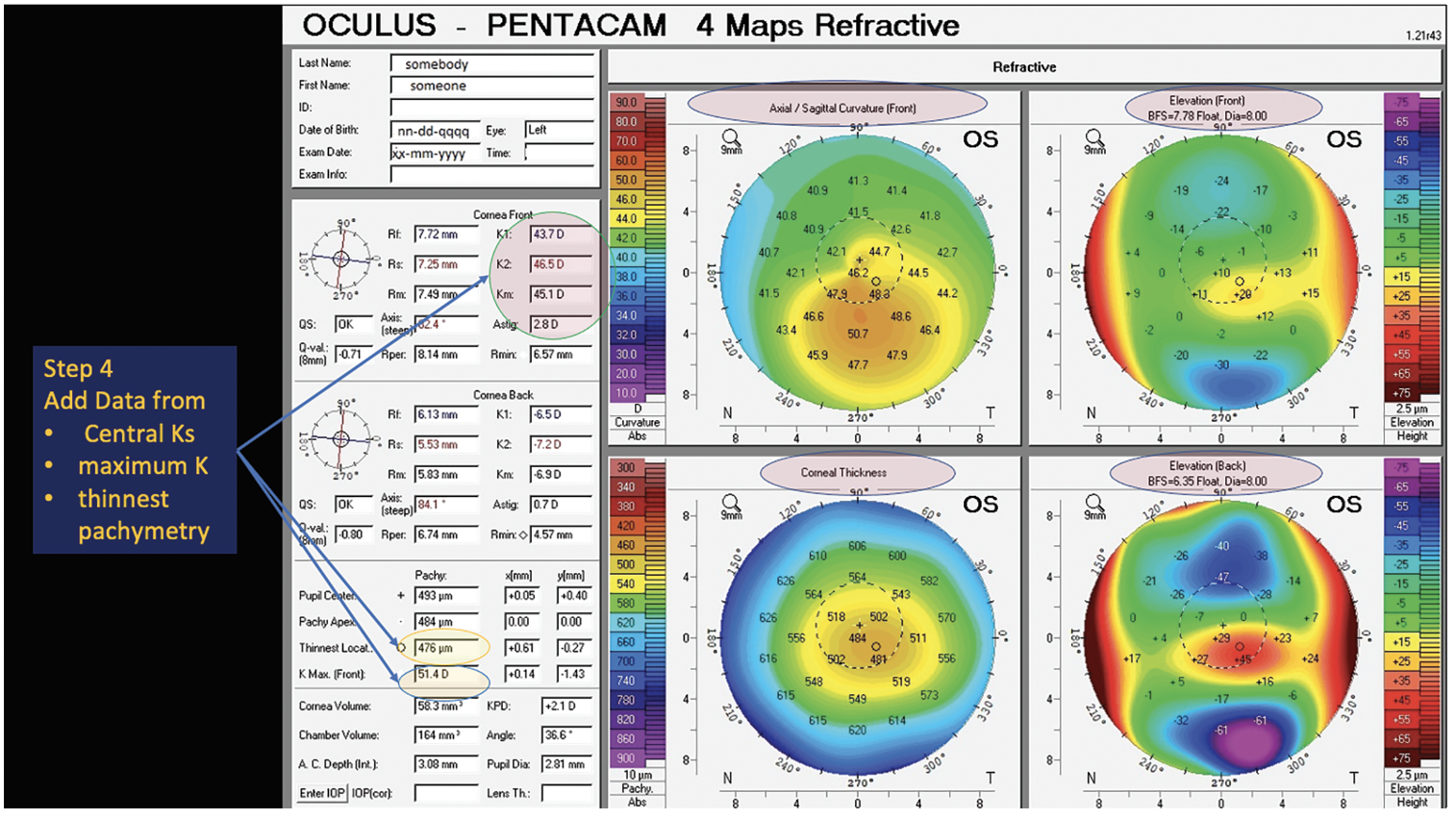

| Figure 2. Most topographers include information on scan quality. Referring to the quality score can help rule out bad-quality scans and artifacts, but experts caution against relying solely on this indicator when evaluating scan quality. |

Objective Screening

“Potential refractive patients will undergo a comprehensive eye exam to evaluate uncorrected and best-corrected vision at distance and near,” explains Dr. Wu. This includes manifest refraction and cycloplegic refraction with cyclopentolate. Additionally, it’s important to check intraocular pressures and do fluorescein staining to screen for ocular surface disease.

“Always look carefully at the lids and lashes,” she advises. “Check for blepharitis and ensure the lids close properly, especially if the patient has a history of blepharoplasty. In some cases, the lids may not fully close after aggressive blepharoplasty, leading to potential exposure issues.” Other key evaluations include dim-light and bright-light pupil size, eye dominance and checking the patient’s current glasses prescription.

Mitchell P. Weikert, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, says that dry eye and ocular surface disease are at the forefront of surgeons’ minds when screening patients. He says that a careful history can help create a picture of a patient’s subjective dryness while a slit lamp exam with fluorescein and/or lissamine green staining and tests such as tear breakup time can paint an objective picture. “We like to see a TBUT of seven to 10 seconds or more,” he says. “When you start to get below seven seconds, it’s not a deal-breaker, but we’ll look more closely.

“Dry eye can masquerade as other things, such as forme fruste keratoconus, so before making any final judgments on corneal shape, be sure that the ocular surface is healthy,” he continues. “On Placido topography, we’ll look for blurring or smudging of the mires and potential reasons behind that. Distorted mires could be a sign of dry eye or ocular surface disease, but it can also reveal epithelial basement membrane dystrophy that might otherwise go unnoticed. There are indices for dry eye [on topography], but I find them more useful when managing a dry-eye patient over time to monitor treatment response. [For refractive screening], we’re getting more of the gestalt by looking at the mires.”

On Placido-based topography, Dr. Weikert says the old-school but still valid I-S value showing the average dioptric power difference between the inferior and superior hemispheres is a good early indicator of inferior steepening. “The I-S value should be below 1.2 to 1.4,” he says. “You can visualize [inferior steepening] when you’re looking at the topography.”

Scheimpflug tomography is the gold standard for corneal evaluation today, says Dr. Prakash. “When trying to determine whether a patient will be a good candidate for corneal-based refractive surgery, we have to map the entire cornea,” he says. “The earlier testing modalities using keratometry or surface topography were limited by the amount of cornea they could cover. If there were pathology in the periphery of the cornea, you might miss it. That’s why Scheimpflug imaging has been revolutionary. Scheimpflug instruments such as Pentacam, Galilei and Sirius have a camera that rotates around the corneal curvature, resulting in a much better, parallax-free image of the periphery, which gives us much more information.”

For ectasia risk assessment, many surgeons refer to the Belin/Ambrósio Enhanced Ectasia Display on Pentacam, an AI-based method for predicting ectasia susceptibility that provides a global view of the cornea. Dr. Prakash explains that this tool analyzes multiple factors, including how the cornea changes in terms of pachymetry from the center to the periphery, the steepest point, the relational thickness (how the cornea changes from point to point) and the overall posterior and anterior surfaces of the cornea, among other metrics.

“It results in a composite algorithm to see whether a cornea is at risk for developing ectasia or not,” Dr. Prakash says. “The D-score has a range of normal, and anything outside of the normal range falls in the yellow zone—where you might think of [doing] a different procedure than LASIK, such as PRK or an ICL—or in the red zone, which is a red flag.”

|

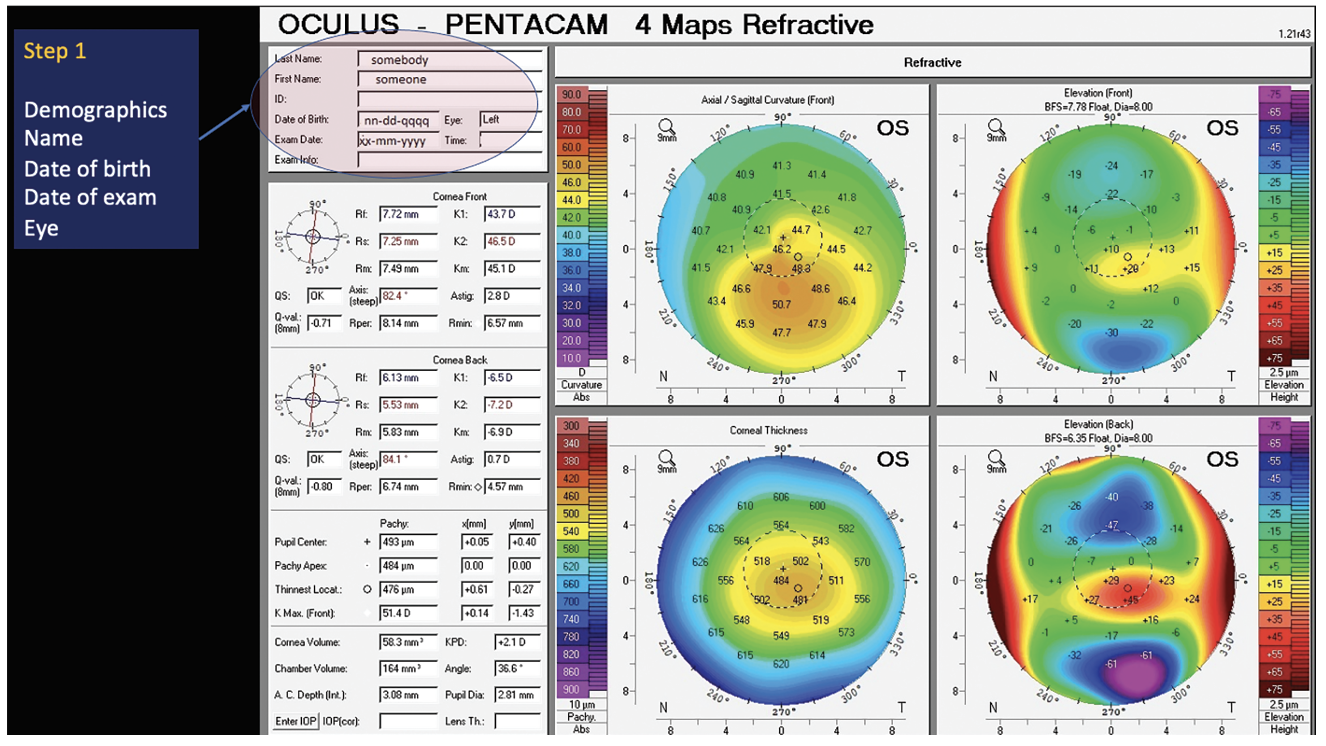

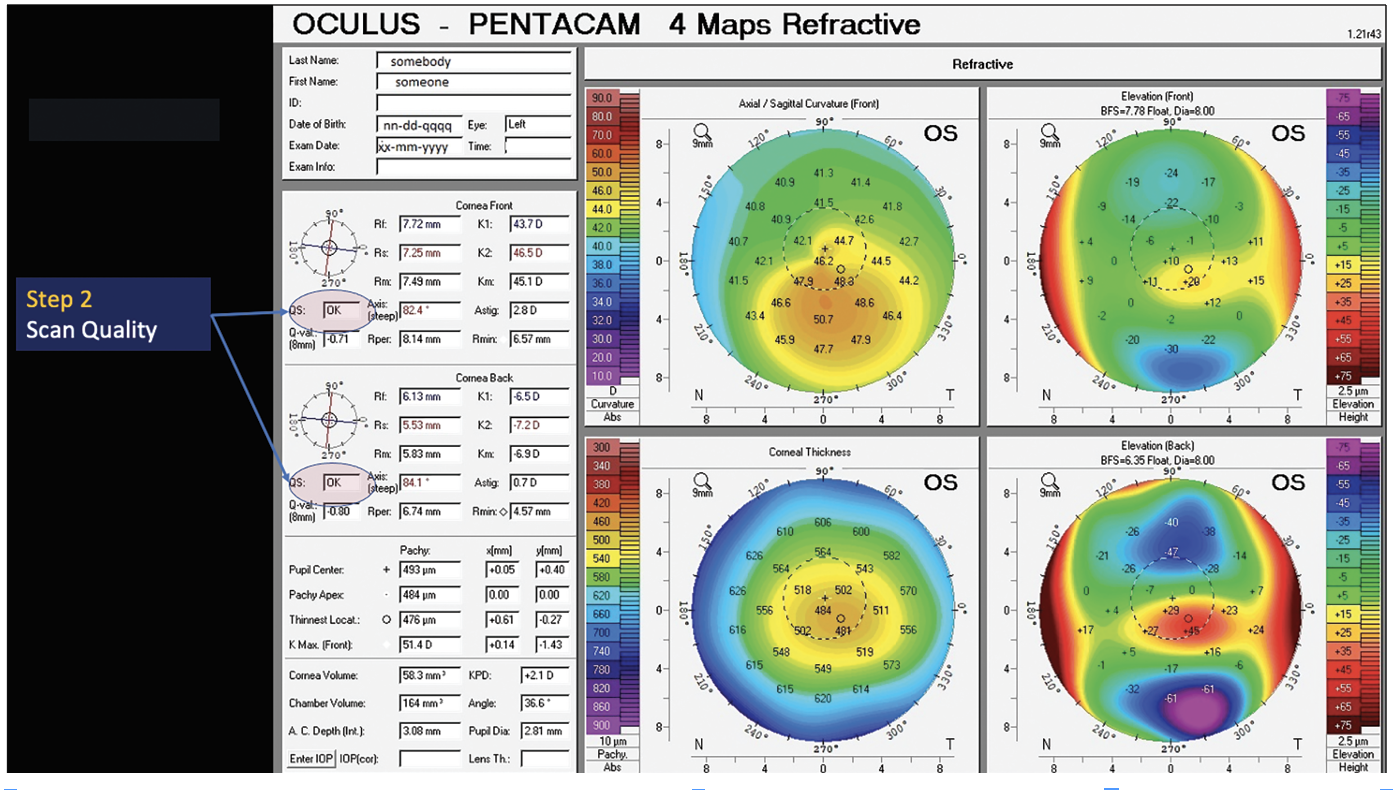

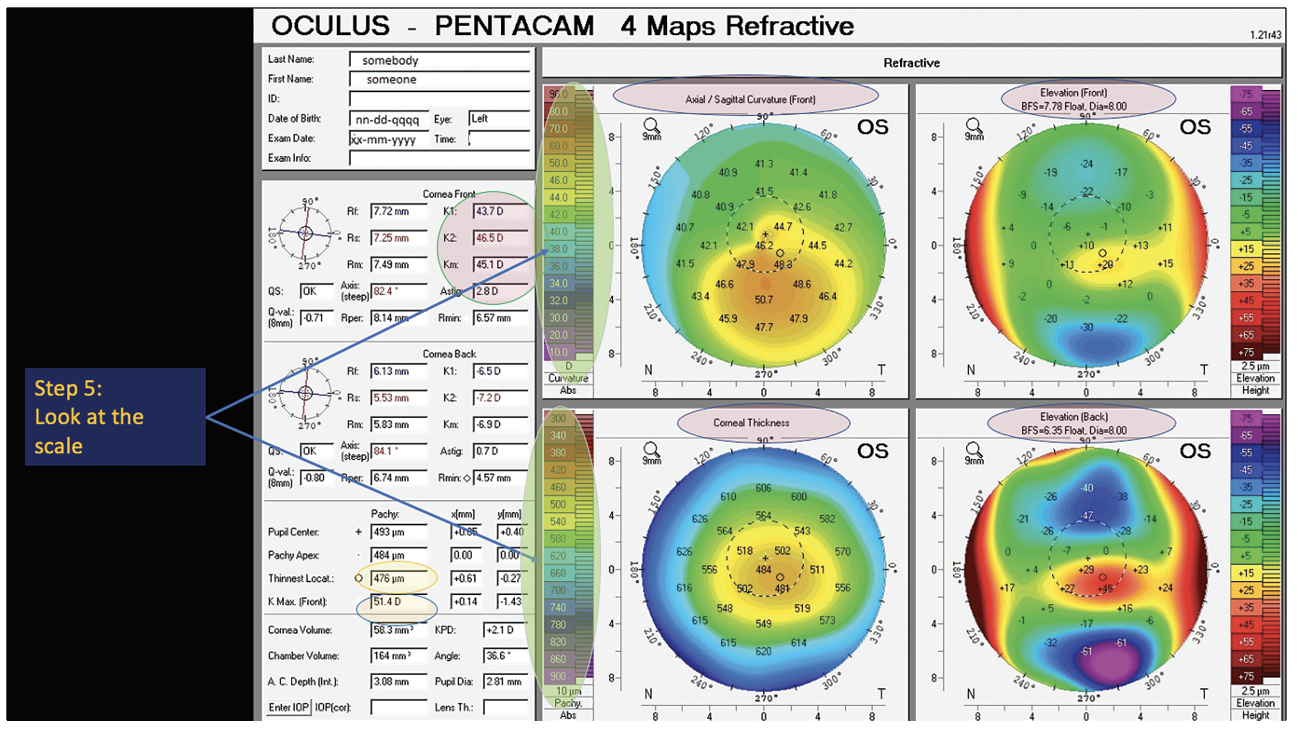

| Figure 3. Double check the labels of each map to ensure you’re looking at the correct one. |

“On the elevation maps, the posterior surface is compared to a reference surface, which is usually a sphere,” Dr. Weikert says. “When you see it deviate from that standard pattern, that will raise your suspicions. You can also use a toric reference surface and do a best-fit sphere or best-fit toric asphere, which will cancel out the normal, regular astigmatism on the elevation maps and reveal irregular, asymmetric astigmatism or foci of abnormal elevation. Other indices such as the posterior asphericity asymmetry index (PAAI), which looks at the difference between the lowest and highest points on the posterior elevation map fit with a toric asphere, can be helpful. If the PAAI is more than 21.5 µm, that’s another red flag.”

Other instruments such as Galilei and Anterion AS-OCT have their own ectasia analysis systems, and the Corvis ST’s air-puff tonometry paired with Pentacam can also supplement analysis. However, there’s no single index or analysis that will flag every patient, Dr. Weikert cautions. “Some may flag one individual and not another,” he says. “If a patient has a small ectasia risk, you’re never going to be able to totally rule someone out with just one device at this point. The more [data] you can get, the better, but you at least need to have the tomography, which gives you [data on] the front and back of the cornea, and the pachymetry across its surface.”

How do you reconcile data from different devices? “If I use five devices and one shows a suspicious index, I’ll have to weigh it by how much faith I have in that particular index versus the others,” Dr. Weikert says. “But, if I see different indices lighting up on more than one device, then that will obviously raise suspicions. A single index on a single device means you need to look a bit deeper, and it may not be a deal breaker.”

He adds that most analysis systems judge whether the patient’s cornea is safe for LASIK. “The indices are developed for post-LASIK ectasia,” he says. “PRK can often still be a safe option since you’re not going as deep into the cornea or creating a flap. That’s not to say ectasia can’t happen after PRK, but it’s less likely.”

Another of many corneal criteria that surgeons consider is percentage tissue altered, or the sum of the flap thickness and ablation depth, divided by the preoperative central corneal thickness. A value ≥40 percent thickness indicates a high risk for post-surgical ectasia.

“I generally don’t do LASIK [on corneas] under 500 µm,” Dr. Wu says. “I typically opt for PRK unless there’s an abnormality in the corneal topography. Depending on the specific abnormality, or if the patient experiences severe dryness, I may refrain from proceeding with either LASIK or PRK. In such cases, addressing the dry eye first and ensuring the cornea is free from fluorescein staining before considering a corneal-based procedure is essential.”

Dr. Wu says that in addition to pachymetry and Scheimpflug and Placido-based imaging, patients also undergo a dilated fundus exam and anterior segment OCT for epithelial thickness mapping. “We typically don’t conduct macular OCT or nerve fiber layer OCT imaging unless there’s a specific indication to do so. For example, if the patient’s vision is inconsistent with the clinical exam, or if there’s uncertainty regarding amblyopia or subtle retinal pathology, we may then opt for additional testing in such instances.”

To mitigate potential false positives from the BAD-D scores, surgeons frequently cross-reference the results with epithelial thickness maps. “We often observe posterior elevation on Pentacam,” notes Dr. Wu. “However, if epithelial mapping reveals a ‘donut sign’—indicating an area of epithelial thinning overlying the area of posterior elevation seen on Pentacam, surrounded by epithelial thickening—it strengthens the likelihood that the posterior elevation seen on Pentacam is genuine. This significantly reduces the probability of proceeding with a corneal-based procedure for that patient.”

Quick Tips for Scans

When evaluating scans, surgeons say to keep these points in mind:

• Check the quality. “It’s simple ‘garbage in, garbage out,’ and if the quality isn’t good—the patient may have been moving or the tester may be new or not have focused the instrument well—then the data is of no value,” Dr. Prakash says. “It’s easy to look at the scan and determine the quality. There are metrics for that, but obviously common sense is important too. If you don’t feel that the scan looks good, do it again.”

• Confirm the patient data. “Double check the EMR, especially when looking at multiple scans throughout the day,” Dr. Prakash says. “Be sure to verify you’re getting the correct patient, the correct eye and the correct date.”

• Double check the scale. “Look at the scale of the scan,” Dr. Prakash says. “Each device has its own criteria because they’re proprietary. Many surgeons are used to a 0.5-D scale and a certain color pattern, but the colors and their corresponding ranges vary slightly from device to device. That said, it’s better to stick to the same device and do the scan a couple of times.”

Determining whether a scan is good or bad takes time. “Especially for surgeons just starting out with refractive surgery, the more scans you see, the more you learn,” Dr. Prakash says. “There’s a finite learning curve, and a bit of an art to assessing a good scan. It’s more than just pure science. You may look at a scan and say, ‘Oh, this looks abnormal,’ even though it looks clinically okay. What do you do? You might offer a slightly safer option or a procedure more suited to that patient. For example, let’s say a patient comes in with a borderline scan for even PRK. You could still do PRK in that patient, but you might want to offer an ICL because it’s a safer option. It’s that overarching principle of safety first.”

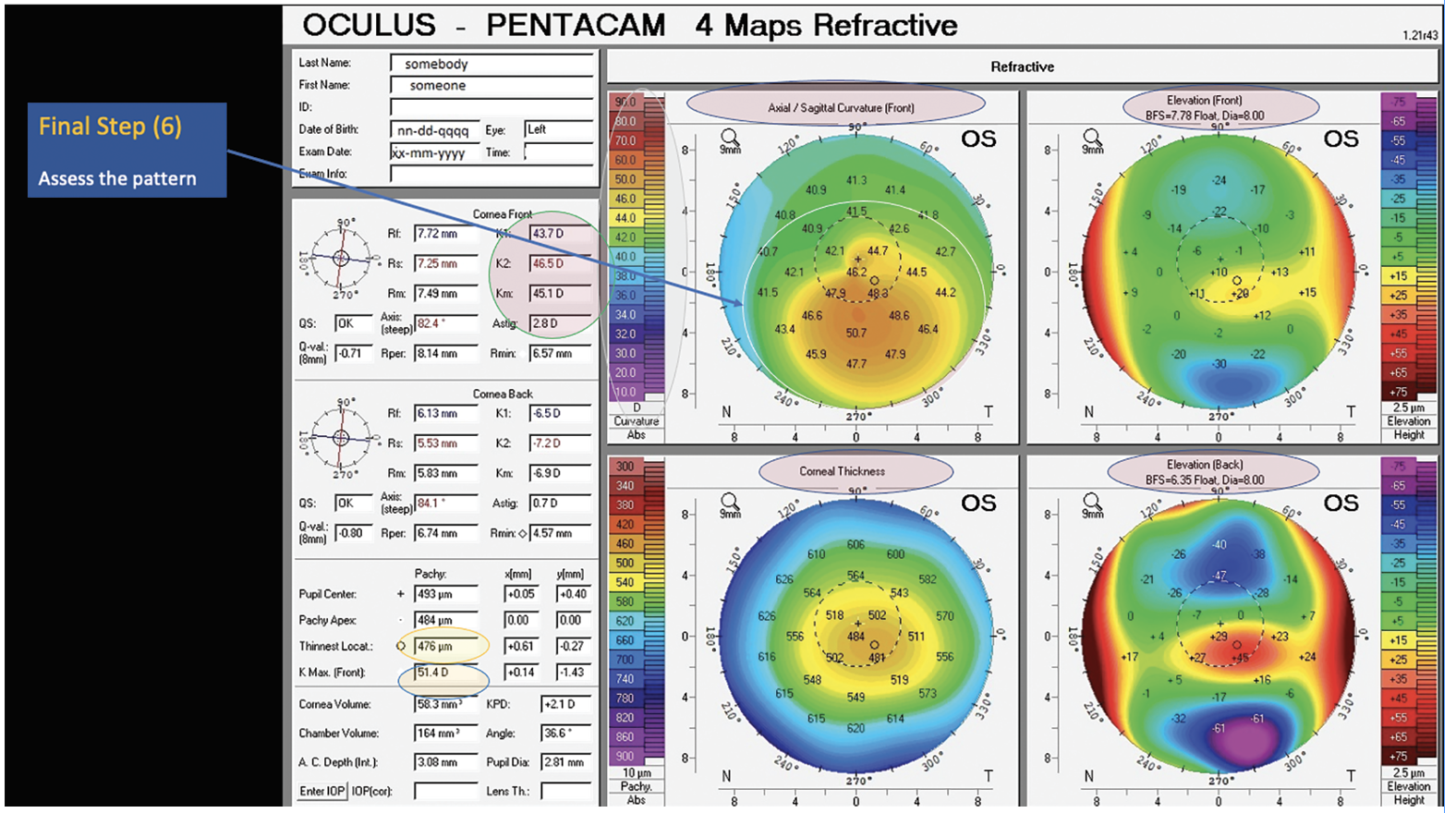

“I don’t think you can beat a visual interpretation of corneal topographic maps,” Dr. Weikert says, agreeing that scan interpretation is more than looking at the numbers. “Looking for symmetric bowties, asymmetric bowties, ‘crab claws’ or other patterns—that pattern recognition is very useful.”

|

| Figure 4. Add the data from central Ks, maximum K and thinnest pachymetry. |

|

| Figure 5. Always double check the scan’s scale, especially if looking at scans from multiple devices since each device has its own proprietary criteria. The corresponding colors and ranges may differ slightly among devices. |

|

| Figure 6. Finally, assess the pattern. Visual interpretation of topography goes hand-in-hand with the numbers. Experts say to look for patterns such as symmetric bowties, asymmetric bowties, crab claws and other patterns. |

Red Flags

What other circumstances should give surgeons pause before deciding whether or not to proceed with a corneal-based refractive procedure? Here are a few key contraindications and some conditions that may warrant additional attention prior to surgery:

• Contact lens overwear or dry eye. Patients in soft contact lenses are instructed to discontinue wear for a week, while those in rigid gas-permeable lenses are advised to wait two weeks at minimum. “If there’s any suspicion of topographic irregularity due to dry eye or contact lens overwear, then we’ll keep the patient out of their contact lenses longer—the longer, the better,” Dr. Wu says. “If irregularities persist, we may schedule the patient for sequential corneal topography and tomography to monitor normalization. If normalization doesn’t occur, we may discuss topo-guided procedures or potentially no procedure at all with the patient. If there are concerns about forme fruste keratoconus or if we’re unsure about the shape and thickness of their cornea, we may explore options such as ICLs or other lens-based procedures.”

• Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. In EBMD, the upper layer of epithelium is a bit loose and doesn’t stick as well to the rest of the cornea, Dr. Prakash says. “These patients might not be good candidates for LASIK, but you can do PRK.”

• Certain skin conditions. “We perform an external examination of the patient’s face to check for conditions such as rosacea or eczema or any other skin disorder that might affect the results of the laser vision correction,” says Dr. Wu. “Atopic dermatitis, for example, can harbor gram-positive bacteria. If patients exhibit eczema around the lids or on the face, we may want to either treat that ourselves or have a dermatologist address it prior to the refractive procedure.”

Another condition to inquire about is keloids. “A keloid is a pathological skin condition,” Dr. Wu explains. “Keloids tend to be more prevalent in people of color, although this is not always the case, so I avoid making assumptions. I ask patients about any surgical scars or other scars they may have. While this association hasn’t been firmly established in the literature, there are numerous anecdotal instances and several published case reports of individuals with keloids experiencing excessive haze after laser vision correction. Therefore, although I have performed LASIK on patients with keloids, I don’t recommend surface ablation for them.”

• Sensitivities and allergies. Managing patients’ allergies beforehand is an important part of the initial screening process. “Patients with uncontrolled allergies may rub their eyes quite a lot,” Dr. Prakash says. “I definitely want to take care of that first.”

He says he once had a patient with papillae who had been referred for refractive surgery due to contact lens intolerance. “The contact lenses were causing the papillae,” he says. “We put her on olopatadine for a few months to control the papillae and then once it was resolved we did the surgery. If patients have active allergies or other triggers we shouldn’t do refractive surgery at that point. Refractive surgery is an elective, planned procedure that should be done only when the eye is most optimized.”

• Previous eye surgery or trauma. “Eye trauma causing a rupture in a cornea unfortunately happens, and any refractive surgery will become very challenging on that eye,” Dr. Prakash says. “In these patients we have bigger issues than to get them out of glasses, so refractive surgery is probably not a good idea.

“For a previous surgery, it depends on what’s been done,” he continues. “Say a patient had cataract surgery done when they were young and unfortunately had a pretty big refractive error left, -4 or -5 D. Or they had cataract surgery when they were young and as they’ve grown, the eye has changed and now they have glasses which are very thick. Refractive surgery is definitely an option provided they have a normal cornea with a stable refractive error.

“Patients with significant, deep scarring on the cornea from, say, a corneal ulcer, may not be good candidates,” he says. “You could do PTK for a faint scar to clean up the cornea and then do PRK.”

Previous retina surgery may require some more planning. “These patients can get refractive surgery, but we’d run it by a retina specialist to make sure there’s nothing else happening in the eye,” Dr. Prakash says. “There’s always a small probability of pushing on the back of the eye, making it weaker, when doing LASIK. That risk is less with PRK, so that’s an option. If a patient who had retinal detachment surgery wants to be less dependent on glasses down the line, we can do PRK but not LASIK.”

• Autoimmune diseases. Performing a comprehensive medical history review can help identify conditions that may indicate poor candidacy for laser vision correction. Dr. Wu explains that she’s less inclined to proceed with a laser vision correction procedure in patients with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, or in those with a family history of autoimmune diseases, due to concerns regarding potential disruption in wound healing or corneal melting. “Studies1 indicate that patients who are well-controlled and don’t have dry eye can achieve good results, and I certainly concur with that,” Dr. Wu adds. “However, as a general practice, I would likely recommend lens-based procedures for such patients.”

She says ICLs are a great option for young patients with autoimmune diseases. “I often prescribe perioperative oral steroids to modulate their wound-healing,” she says. “Generally, the dry eye resulting from a lens-based procedure is more manageable and shorter-lived than a corneal-based procedure.” Similarly, Dr. Wu says she exercises an extra degree of caution in patients with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. “These patients may experience poor epithelial wound healing and an increased risk for infection, making them less suitable for PRK, and I may lean toward LASIK instead. If their disease is poorly controlled, they have diabetic retinopathy and they’re young, then then they may not be the most suitable candidate for any sort of procedure.”

• Neurologic conditions. “It’s important to ask about systemic conditions that may be associated with nerve abnormalities, such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes, autoimmune disease, small fiber neuropathy or fibromyalgia,” Dr. Wu says. “Damage to the corneal nerves from trauma, surgery, dry eye or underlying systemic conditions can cause the nerves to regenerate abnormally, resulting in their sending off pain signals without a stimulus or with a subthreshold stimulus. Individuals may, for example, be oversensitive to light or wind hitting their eyes. Some cases of corneal neuropathic pain have resulted in suicide. While it’s a very rare condition that occurs in perhaps 1 in 10,000 cases or less, it’s a devastating outcome that can occur after ocular surgery.

“The most significant associations with corneal neuropathic pain are anxiety, depression, PTSD and migraine headaches,” Dr. Wu explains further. “When patients mention having any of these conditions, I inquire about the duration, medications they use to manage symptoms, and whether they’ve ever been hospitalized for them. I discuss neuropathic pain with every patient, informing them about what’s considered normal after laser vision correction—typically a few days of discomfort after PRK and perhaps a day or less after LASIK—so they have realistic expectations. I emphasize that we don’t expect prolonged eye pain beyond these periods and encourage them to inform us if they experience symptoms. If necessary, we can use confocal microscopy at our center to image their nerves and assess if any abnormality is present in terms of nerve regeneration.”

Dr. Wu says corneal neuropathic pain is more manageable if it remains localized to the peripheral nervous system. “If it’s early and it stays within the cornea, treatment is relatively straightforward. However, if it evolves into centralized pain, management can be more challenging. In these cases, patients may require agents such as gabapentin, pregabalin or other tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline or low-dose naltrexone, which target the central nervous system.

“Patients with a history of fibromyalgia or existing neuropathic pain elsewhere in the body from conditions like diabetes, especially if they’re already on medications like gabapentin, may be at higher risk for this outcome,” she continues. “While this doesn’t necessarily rule out refractive surgery, I may advise against corneal-based procedures in these cases. However, it’s important to note that neuropathic pain can also occur after lens-based surgery, so open communication about potential risks and expectations is essential—not to alarm patients, but to prepare them for what may occur and what constitutes abnormal symptoms.”

Dr. Wu explains that patients at greater risk for this outcome may have what’s called “pain without stain,” experiencing symptoms of dry eye without the typical signs. “Everybody has seen these patients in their clinic if they’ve been in practice long enough,” she says. “They may mistakenly attribute their symptoms to psychiatric causes due to the overlap with anxiety and depression.”

• A history of herpes. “I inquire about any history of fever blisters or cold sores,” says Dr. Wu. “Typically, it’s necessary to inquire whether patients had cold sores during childhood, as they may not associate herpes with their condition if they haven’t experienced a cold sore in a long time. If there’s a history of herpetic infection, I usually prescribe valacyclovir or another oral antiviral around the time of their laser vision correction. Procedures such as cataract surgery or those involving excimer lasers can activate herpes in the cornea due to UV light exposure or the trauma of surgery itself. Therefore, patients need not have a prior history of ocular herpes for concern. However, I do consider a history of ocular herpes a contraindication for laser vision correction.”

Dr. Wu gives patients with oral or skin herpes either a maintenance or a treatment dose of antiviral medication. “The full treatment dose for herpes simplex virus is valacyclovir 500 mg three times a day or famciclovir 250 mg three times a day. You can also give acyclovir 200 mg five times a day, but I usually give 800 mg three times a day for convenience. For herpes zoster treatment, it’s double the simplex dosage—valacyclovir 1 g three times a day, famciclovir 500 mg three times a day and oral acyclovir 400 mg five times a day.”

• Medications. Patients who are taking or have taken medications that are known to cause dry eye, such as Accutane or multiple glaucoma medications, often are not considered ideal candidates for corneal-based procedures.

When examining potential surgical candidates, Dr. Wu examines the meibomian gland structure and expresses the glands to evaluate for meibomian gland dysfunction. “If they have significant meibomian gland dysfunction, I inquire about Accutane usage,” she says. “Sometimes these patients may exhibit severe meibomian gland dysfunction, making PRK less suitable for them. They may achieve better outcomes with LASIK or alternatively, if they have moderate to severe dry eye—which is common after Accutane use—a lens-based procedure may be more appropriate.”

Dr. Wu, Dr. Weikert and Dr. Prakash have no related financial disclosures.

1. Schallhorn JM, Schallhorn SC, Hettinger KA, et al. Outcomes and complications of excimer laser surgery in patients with collagen vascular and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery 2016;42:12:1742-1752.