Though the use of Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty has become more common, there are still patients for whom penetrating keratoplasty is the only option. For these patients, managing their post-PK astigmatism becomes the next order of business. In this article, I’ll review how I treat these cases.

The Evaluation

When approaching a case of astigmatism after PK, it’s important to know the reason the patient had the transplant. This will help guide your management decision.

After practicing for 26 years, I’ve noticed that patients who develop astigmatism after PK are usually patients with keratoconus. Interestingly, after you remove the sutures from these patients, you’ll sometimes see the astigmatism increase year after year. This occurs because these patients have a further emergence of ectasia in the corneal transplant. The approach to such a patient is different from someone who had a PK due to trauma, herpes or Fuchs’ (in older patients who had transplants before the advent of DSAEK and DMEK).

|

In the first month post-PK, I look at the level of corneal edema and epithelial healing, and focus on surface rehabilitation and dryness. After the first three months, we still evaluate the ocular surface integrity, dryness, possible tissue rejection and inflammation, but the priority shifts to the topography and the refractive error.

Three months postop, I evaluate the topography in earnest and perform a detailed refraction. We perform and refine the refraction, identifying the axis of astigmatism. When viewing the topographic map, we try to determine if the tissue was distributed properly, the trephination was well-centered, and the corneal tissue was properly distributed when they sutured it, and we check the eccentricity and quality of the trephination in the donor and the host. We also use tomography. Even though topography is still my number-one tool for deciding how to selectively remove the sutures and get a handle on the astigmatism, tomography helps me see if the corneal thickness and tissue distribution make sense.In the first month post-PK, I look at the level of corneal edema and epithelial healing, and focus on surface rehabilitation and dryness. After the first three months, we still evaluate the ocular surface integrity, dryness, possible tissue rejection and inflammation, but the priority shifts to the topography and the refractive error.

|

The beauty of corneal tomography is that it gives you a volumetric analysis. It’s not just measuring anterior elevation; it also gives some idea of the posterior elevation and the overall corneal thickness. When looking at the topography, I note the K1 and K2 values, and whether the pattern of astigmatism is orthogonal. If it is orthogonal, then the visual recovery will be better. If it’s not—which, unfortunately, is often the case—you then attempt to make it more orthogonal by removing certain sutures, which leads us to a discussion of astigmatism management.

Tackling the Astigmatism

Here are the current approaches to managing post-PK astigmatism, from early postop to years later.

• Suture removal. In the immediate postop period, when the patient still has the transplant sutures in his cornea, you can adjust the astigmatism by manipulating the sutures. If a patient has interrupted sutures, you can judiciously remove some to try to redistribute the tissue and lessen the astigmatism. In evaluating the astigmatism, you may find that the sutures are tighter, and the astigmatism higher, in some meridians. You can remove these systematically to adjust the astigmatism. If I have a patient with interrupted sutures, I usually start removing them every couple of weeks, starting after the first 12 weeks postop; I usually remove one to three at a visit, based on the topography and the tightness of the sutures.

|

On the other hand, if the patient has running sutures, it’s harder to control the astigmatism with selective suture removal because if you cut the suture anywhere, it all has to come out. However, in some cases of running sutures, I’ve chosen to take the patient to the minor procedures room at about four weeks postop, removed the epithelium, and tried to rotate the sutures. I try to loosen the quadrants that are tight, and tighten the sutures in the loose quadrants. This isn’t as effective as working with interrupted sutures, of course, and the results are variable.

Once the sutures are out, and it’s a year or two postop, you have to look to other options. Usually, this type of patient has a lot of anisometropia, and can’t, or won’t, tolerate wearing contact lenses. Here are your options:

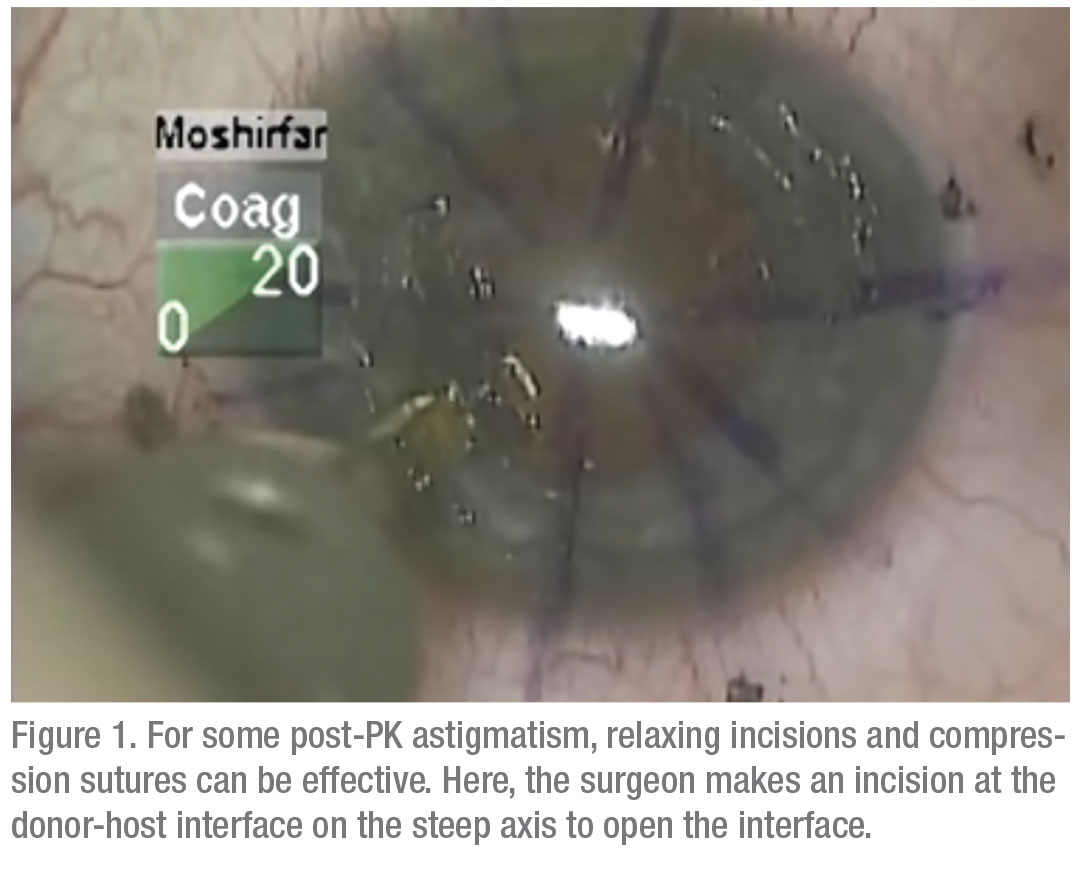

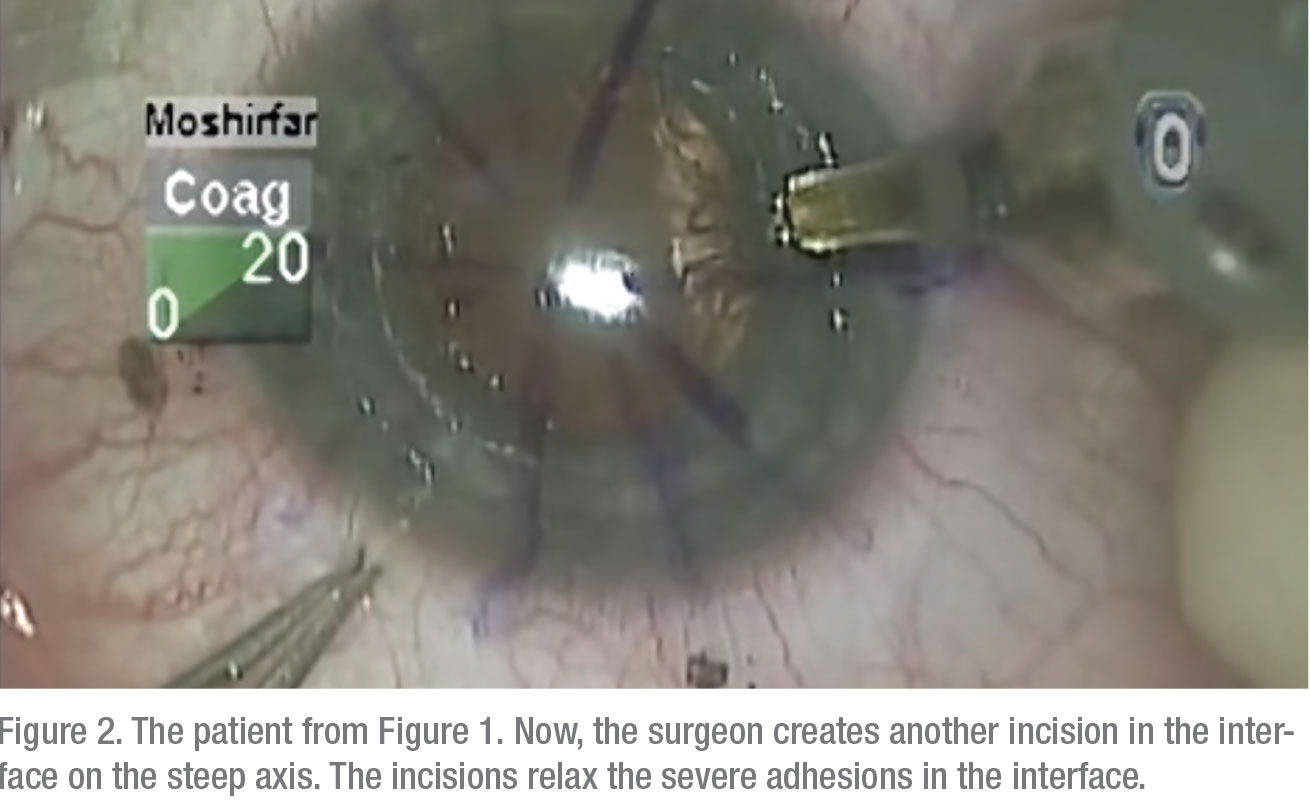

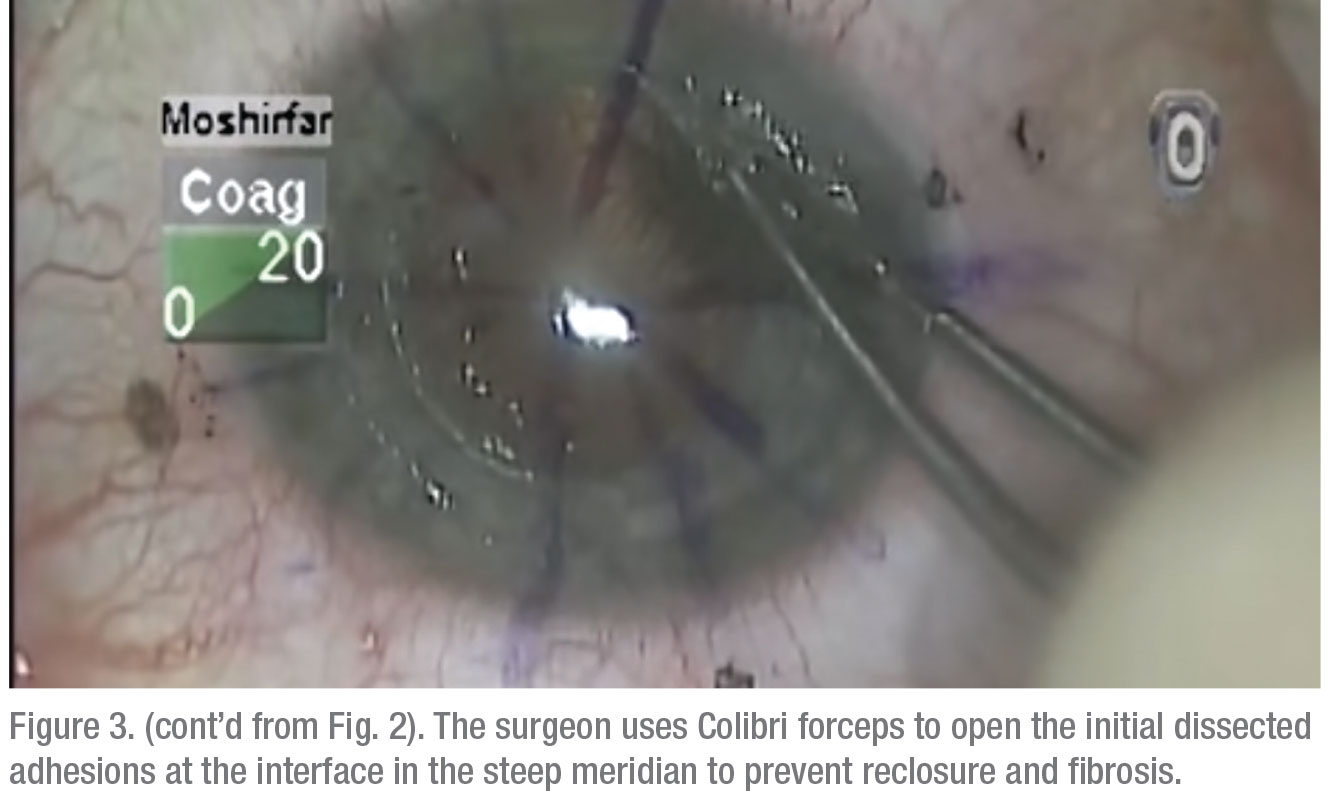

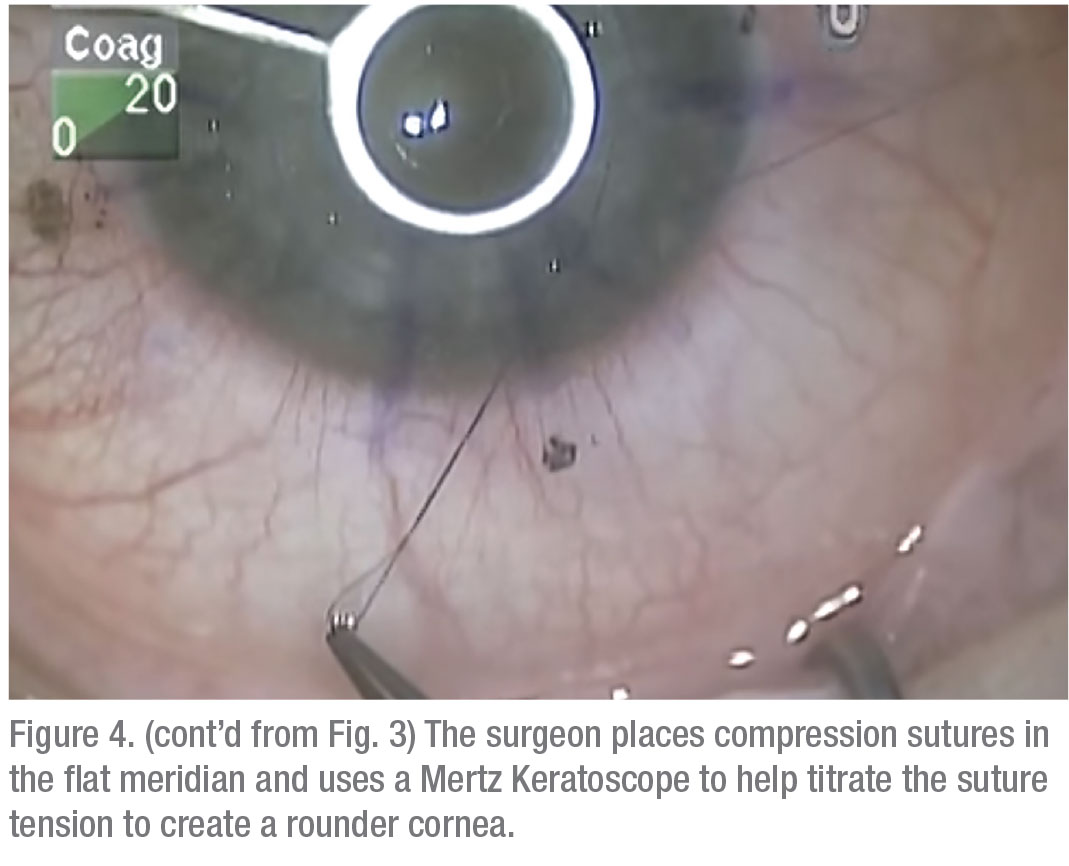

• Relaxing incisions/compression sutures. If the astigmatism is very orthogonal and symmetrical, i.e., it has that nice figure eight configuration, and it’s less than 6 D, many times you can do a relaxing incision in the steep meridian of the donor/host interface to reduce the astigmatism. On the other hand, if it’s greater than 6 D—more like 8 D—sometimes you need to both place a relaxing incision in the steep meridian at the donor/host interface and place some compression sutures in the flat meridian 90 degrees away. Topography is invaluable for planning both the relaxing incision and the placement of any compression sutures.Once the sutures are out, and it’s a year or two postop, you have to look to other options. Usually, this type of patient has a lot of anisometropia, and can’t, or won’t, tolerate wearing contact lenses. Here are your options:On the other hand, if the patient has running sutures, it’s harder to control the astigmatism with selective suture removal because if you cut the suture anywhere, it all has to come out. However, in some cases of running sutures, I’ve chosen to take the patient to the minor procedures room at about four weeks postop, removed the epithelium, and tried to rotate the sutures. I try to loosen the quadrants that are tight, and tighten the sutures in the loose quadrants. This isn’t as effective as working with interrupted sutures, of course, and the results are variable.

|

• Toric ICL. The toric version of the Staar ICL was recently approved, giving us a new option for patients. If the patient is pseudophakic and has significant but orthogonal and symmetrical astigmatism, a toric ICL could be a good option. The benefit of the toric ICL is that it takes care of any myopia as well as the astigmatism.

• Refractive lens exchange/toric IOL/femto incisions. In some cases, if the astigmatism is orthogonal and symmetrical, the patient’s cornea is otherwise normal and the patient is in the early cataract age range, sometimes RLE with the placement of a toric intraocular lens is a good option. An example of this would be the 62-year-old post-PK patient who comes to me with high astigmatism and high myopia, and has problems wearing contact lenses.

In some of these RLE patients, their astigmatism is too high to be corrected with just a toric IOL. For them, I follow the surgery with femtosecond-created, intrastromal arcuate keratotomy incisions located about 1 mm inside the donor/host interface. Sometimes I open these incisions at the time of their creation, sometimes not. In the latter, I’ll return another day to try to titrate their effect by opening them.

• Laser refractive surgery. In the past, surgeons tried LASIK for these patients, but found that the results always regressed. At this point, for selected patients, PRK with adjunctive mitomycin-C has actually proven to be a better option. The candidates for this are usually anisometropic, with unilateral pathology (maybe a corneal laceration), who’ve had their cornea, iris or lens changed and we’re not willing to perform a piggyback IOL procedure on them for some reason.

One note, though: if these patients have an old graft (older than eight years), sometimes they have significant endothelial edema, which will result in corneal folds and edema for weeks after the PRK before the eye eventually recovers. These patients can have retarded epithelial healing and may still develop haze in spite of the mitomycin use.

• Wedge resection. If the astigmatism is over 8 D, you may have to consider revising the corneal wound by way of a wedge resection. In the wedge resection, we selectively remove some tissue from certain quadrants. It’s a classic approach that corneal surgeons have developed to manage a wide range of astigmatism.

• Regraft. Some problems are too big for a wedge resection, and require a new graft. For example, if the patient has 12 D of astigmatism eight or nine years postop, a regraft may be the best option. The regraft involves trephinating the cornea with a larger size, and re-transplanting a larger graft.

Though there’s not a lot of reimbursement for these post-PK procedures, much of the reward comes from improving patients’ vision and overall quality of life.

Dr. Moshirfar is medical director of the Hoopes Vision Refractive Research Center in Draper, Utah, and a professor of ophthalmology at the Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah.