For that identification to happen, people need to hear the message about glaucoma from someone they can trust, relate to and approach. With that in mind, this article is my call-to-action for ophthalmologists, glaucoma specialists, optometrists and anyone else who is seeing patients with glaucoma. Here are some ways you can help ensure that your patients are educated about glaucoma and its hereditary component, and a few strategies you can share with patients to help them convey the information to their family members.

The Importance of Heredity

Genetic studies have suggested that more than 50 percent of glaucoma is familial.1 It’s very strongly hereditary, especially among siblings; the rate of glaucoma can be 10 times higher among individuals with a sibling who has glaucoma. For example:

• The Baltimore Eye Survey not only found that open-angle glaucoma was much more prevalent in African Americans than Caucasians, it also found that if there was a family history of glaucoma the risk of developing glaucoma was significantly higher. That risk was even higher within the African-American population, and was highest among siblings.2

• A study of 2,500 African-American individuals being conducted at the Scheie Eye Institute in Philadelphia found that those with a family history of glaucoma were 3.5 times as likely to have glaucoma as those with no family history of the disease; the risk was even greater if it was a sibling that had glaucoma. A family history of glaucoma was also associated with more aggressive disease, a three-year-earlier onset and a greater likelihood of undergoing glaucoma surgery.3

• Tasmanian studies also found that glaucoma occurs about three years earlier and was more severe when other members of the family had had the disease.4,5

• The Barbados Eye Study looked at more than 1,000 relatives of about 200 glaucoma patients who were followed for nine or 10 years. Out of those relatives, about 23 percent who were examined had glaucoma. In fact, the researchers found that the second highest risk factor for developing glaucoma was glaucoma being part of the family history.6,7

• The Rotterdam Eye Study in the Netherlands found that having a family history of glaucoma increased the risk of a family member having glaucoma ninefold.1

All of this data shows that family history matters, so if you have a patient with glaucoma you will probably also find it in other family members. It’s likely that at least 15 percent of our glaucoma patients have at least one sibling who has glaucoma, and that individual may be totally unaware of the disease. In other words, our patients are linked to a population of individuals who are much more likely to have glaucoma than a random sample of people. That means we have an opportunity to reach out to a number of individuals who have glaucoma but don’t know it—without having to cast too wide a net.

|

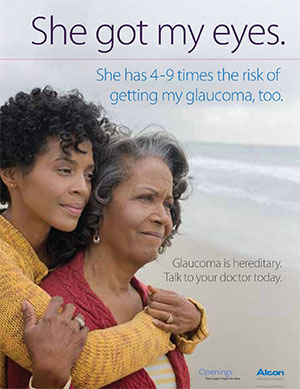

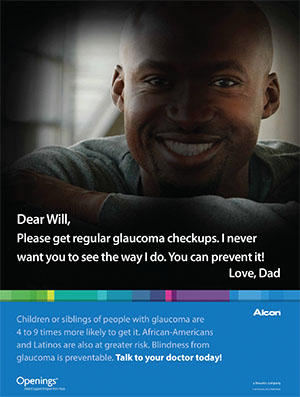

One easy way to alert glaucoma patients in your office to the likelihood that family members may be at risk is to display posters like the ones shown above and on p. 62. Both are available at no cost from Alcon. |

Clearly this is an avenue worth pursuing. However, there are two practical problems: First, communication within families is often incomplete, making pa-tient reports of family history somewhat unreliable, and making the sharing of information with other family members potentially awkward. Second, as physicians we tend to be pressed for time, making it seem like a daunting task to pursue this concern with most of our glaucoma patients.

Intra-family Communication

There’s not much question that the odds of a family member getting screened increase dramatically if that family member understands the nature of glaucoma and the fact that it runs in families. That makes it crucial to get the word out to our patients’ blood relatives. The problem is, even if we manage to educate each and every glaucoma patient, there are other obstacles to reaching family members.

In general, when patients are already being treated for glaucoma, the outlook for spreading the news is good. The Baltimore Eye Survey found that most patients who were in the system, diagnosed and being seen, knew a lot more about their family history of glaucoma than individuals who weren’t being treated. That suggests that when they were diagnosed they were educated about the family history component, and other family members had been willing to share their health histories. But someone who is newly diagnosed is most likely not aware of how glaucoma works, or any family history of the disease.

Another issue that relates to this is that not every family shares their health history. The Tasmanian glaucoma study found that nearly 30 percent of the time glaucoma patients didn’t realize that other family members did have glaucoma. Along these same lines, I did some research when I was a resident at Wilmer Eye Institute trying to target family members who were at risk for glaucoma.8 We asked glaucoma patients what they knew about glaucoma; then we asked if it was OK to call family members to find out how much they knew. Were they aware of their family’s positive history of glaucoma? Did they know that glaucoma can be hereditary? Had they ever been checked for glaucoma?

What we found was that in Baltimore, only 77 percent of the family members we spoke to knew our patient had glaucoma. And when other family members reported having glaucoma, only 61 percent of our patients knew about it. So there’s some level of disconnect within families when it comes to talking about a glaucoma diagnosis.

In addition, we found that there was a mental disconnect between the idea that glaucoma is hereditary and the reality that this means family members are at risk. When we talked to our patients who were aware that there is a hereditary component, 30 percent of them still didn’t think it was important to tell their family members about the diagnosis and ask them to get their eyes checked.

The bottom line is that educating patients about glaucoma being hereditary is often not sufficient to get them to spread the word. Patients may not make the connection that this means family members are also at risk; they may not be aware that other family members have already been diagnosed; and they may not bother to pass along the information to other family members who are at risk.

Better Educating Patients

All of this means that we have a critical role to play when patients come into the system, to educate them about the hereditary component of glaucoma and the fact that it runs in families, and to do as much as possible to get patients to spread the word and encourage family members to get screened.

Here are some strategies that will help ensure that your patient’s family members get checked:

• Make this a regular part of your discussion when a patient is diagnosed with glaucoma. Many times my patients say, “Thank you so much for letting me know and giving me this information,” because they care about their family members and they don’t want them to go blind. This discussion gives them a sense of responsibility. It usually takes less than 60 seconds to have the conversation before you leave the room.

• Don’t assume that patients will make the connection between glaucoma having a hereditary component and family members being at risk. The reality is that we need to spell things out very clearly. We have to convey that it’s important for the patient to let the family know that some family members may be at risk of vision loss, and that they all should be checked regularly.

• Suggest that patients make a point of asking family members if they have glaucoma. The research mentioned above indicates that awareness of glaucoma in the family is not guaranteed. The only way to be sure is to ask. If there’s a family history of glaucoma, it may make a difference in how carefully our patients need to be followed, since those with a family history tend to have more aggressive disease. Asking about family health history also gives your patient a platform to spread the word about familial risk.

• Frame the sharing of this in-formation with family as a gift, not a burden. Some family members may take the attitude that getting screened is like looking for trouble: Everything is fine, don’t make me seek out bad news. We need to make it clear to patients that glaucoma may have no symptoms at first, but the earlier glaucoma is caught, the easier it is to treat. Encouraging family members to get checked is a way to make sure they don’t lose vision, because once they do, they can’t get it back. Sharing this information with family members is potentially giving them the gift of sight, even if it feels like a burden to bring it up.

• When relatives come in with the patient, take the opportunity to talk to them about this. This is a chance to spread the word among the very group that’s at elevated risk. You could even suggest that they make an appointment to get screened while they’re in your office.

• Get your staff to help spread the message. Staff members who are aware of the patient’s diagnosis can help spread the message that family members should be screened.

• Suggest that the patient mention this at family gatherings. Often, this is a good opportunity not only to spread the word but to get valuable family health history information, when multiple family members are present and can contribute their knowledge.

• Host your own screenings for the family members of your patients. Consider hosting a once-a-year event at which you provide free screenings for family members of your glaucoma patients, perhaps during glaucoma awareness month, or World Glaucoma Week. Then, make sure your patients know about it. Offering a free special event may inspire people to get checked who would otherwise not bother. (And be sure to participate in community screenings, especially in areas with higher African-American populations, or environments with primarily elderly individuals.)

|

• Partner with patients who have large family reunions. If some of your patients have family re-unions attended by a large number of individuals, consider offering to arrange a free screening during the reunion.

• Participate in programs that provide free care, such as the AAO Glaucoma EyeCare Program. Having this option available removes a major roadblock for family members who aren’t insured.

• Put up posters in your waiting area and exam rooms. Even with my personal passion for this cause, the realities of a busy clinical practice often used to leave me feeling like I had failed to communicate the issue of glaucoma running in families as completely as I should have. We’re all trying to be efficient and make sure we get to the next patient in a timely manner, so it’s easy to forget to mention that family members are also at risk and should be getting checked for the disease.

To help remedy that, I worked with Alcon to develop two posters that address this issue; they can be put up in your waiting room and/or exam rooms. The hereditary posters (shown on p. 61 and 62) include statistics about glaucoma and how members of the family are at higher risk; they talk about how untreated glaucoma can lead to blindness, and how being screened is important.

I’ve found that having these posters in the office greatly increases the likelihood of a discussion about getting the family screened. Either the patient points out the poster and asks about it, or I see it and it reminds me to mention the subject before I leave the exam room. Sometimes I’m in the room with family members, and they see the poster and start the discussion.

Having the posters up has made a big difference in terms of getting family members to come in. I’ve even had patients request copies of the posters to put up in their workplace. (Your drug rep should be able to get the posters for you.)

• If your glaucoma patient is young, suggest that younger family members be screened as well. If your patient is younger—say, in his 40s or 50s—with moderate or worse glaucoma, I would definitely tell him to get his teenage kids checked. (I sometimes treat glaucoma patients as young as 6 years old.) If the primary patient is diagnosed in the late 60s or later, I would suggest having family members in their 20s or older be screened. The age of diagnosis and stage of disease upon presentation gives you a sense of how aggressive the disease may be.

• Provide your glaucoma patients with pamphlets or brochures addressing this. It’s a lot to ask patients to remember all the details about why glaucoma is so problematic. A take-away brochure that can be passed along to family members can help ensure that complete information makes its way to those who are at risk. You can also provide links to videos that family members can watch. (We need to come up with more ways to encourage patients to spread the word, even if they have mixed feelings about starting the conversation with family members themselves.)

• Join my campaign to make sure family members get screened. There’s a lot that we can do to make sure this population of at-risk individuals doesn’t sneak under the radar. Many of the strategies I’m suggesting here are very simple, fast and free; we don’t have to do anything heroic. Meanwhile, these small steps could have a major impact on the disease. I think if we encourage physicians across the nation and around the world to pursue this, we can definitely reduce the number of people with glaucoma who remain undiagnosed (currently estimated at 50 percent).

Because of the nature of the doc-tor-patient relationship, we have a significant opportunity to educate patients about glaucoma. For the patient, the message is most likely to be heard if it comes from you. For the family member, the message is most likely to be heard if it comes from your patient. Hearing this from a family member can be much more motivating than hearing it from a public service announcement; people actually will make the effort to get checked.

Please join me and make a commitment to reaching your patients’ family members and encouraging them to get screened. We can definitely be more aggressive and creative about telling our patients how important it is for them to spread the word and urge family members to get checked. I’m already working with a number of individuals and organizations to further this cause. If a significant portion of eye-care professionals also make a commitment, we can have a major impact on reducing the number of undiagnosed individuals with glaucoma. REVIEW

Dr. Okeke is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Va., and a glaucoma specialist and cataract surgeon at Virginia Eye Consultants. You can reach her at iglaucoma@gmail.com.

1. Wolfs RC, Klaver CC, et al. Genetic Risk of primary open-angle glaucoma: Population-based familial aggregation study. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:1640-1645

2. Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Family history and risk of primary open angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:1:69-73.

3. Sankar P, Miller-Ellis E, et al. Family History in the Primary Open-Angle African American Glaucoma Genetics (POAG) Study Cohort. AAO Poster Presentation Nov 2015.

4. McNaught AI, et al. Accuracy and Implications of a reported family history of glaucoma experience from the Glaucoma Inheritance Study in Tasmania. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:7: 900-904.

5. Wu J, et al. Disease severity of familial glaucoma compared with sporadic glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:7: 950-954.

6. Leske MC, Wu SY, et al. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: The Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1:85-93.

7. Nemesure B, He Q, et al. Inheritance of open-angle glaucoma in the Barbados family study. Am J Med Genet 2001;103:1:36-43.

8. Okeke CN, Friedman DS, et al. Targeting relatives of patients with primary open angle glaucoma: The help the family glaucoma project. J Glaucoma 2007;16:6:549-55.