Advancing technology has obviously improved the treatment of eye disease for patients and ophthalmologists alike during the past 20 years. However, some advances have exposed pockets of uncertainty for all specialists involved—one way or another—in cataract and refractive surgery. Varying standards for managing surgical risk to the retina and optimal vision have emerged, spurring a quiet debate among some anterior segment surgeons and retinal specialists.

“Small-incision refractive cataract surgery, femtosecond lasers, wavefront technology, intra-operative aberrometry, new technology IOLs, LASIK, and PRK—combined with today’s marketing—have increased patients’ postop expectations of quality of vision,” says Steve Charles, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Tennessee Hamilton Eye Institute. “There’s a substantial emphasis in our profession on refractive surprises associated with cataract surgery—and an insufficient focus on visual surprises, primarily associated with macular disease, co-existing with cataract. Avoiding both types of surprises should be priorities.”

In this article, surgeons discuss strategies they have developed—and that you can use—to try to benefit both parts of the eye.

|

|

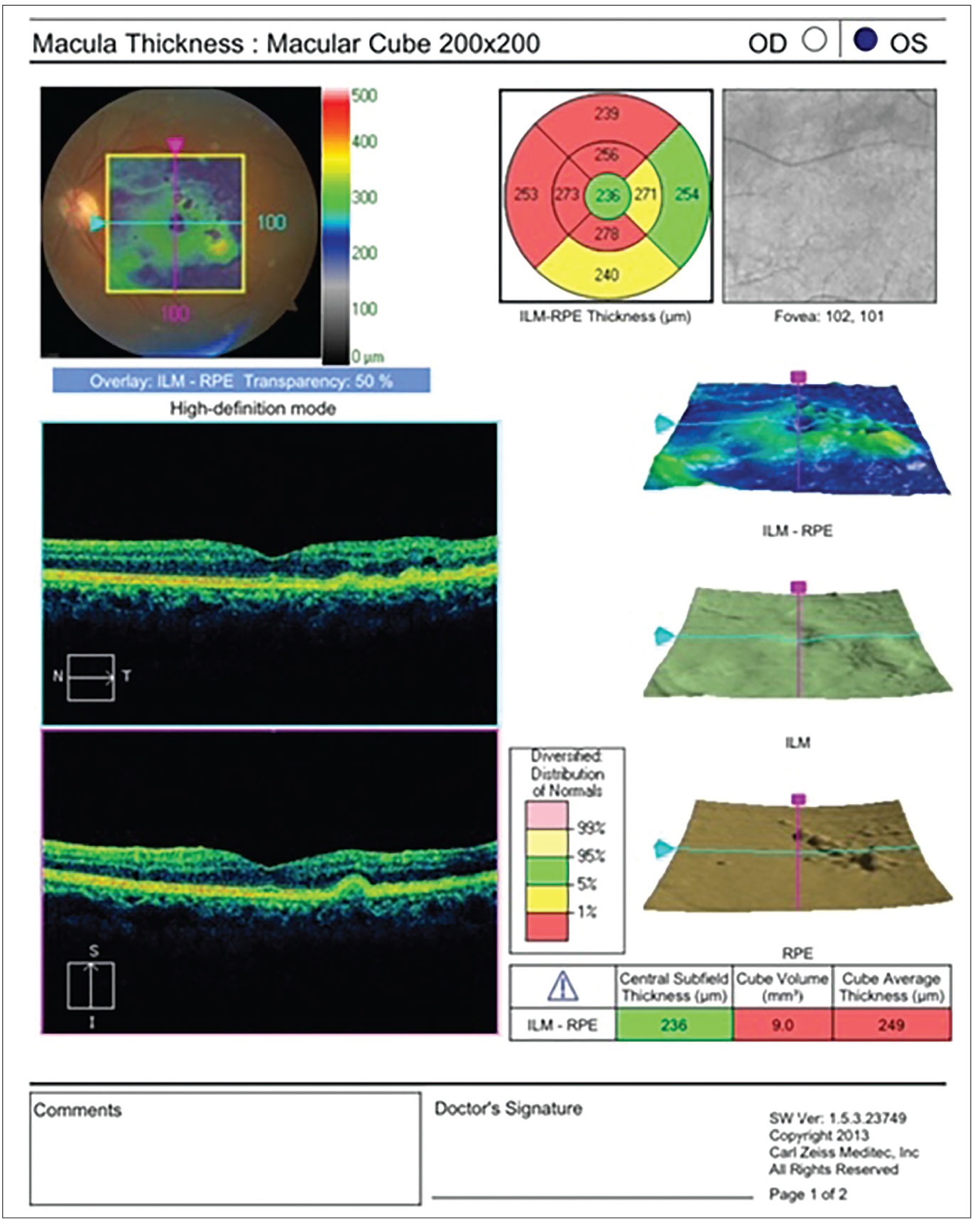

Figure 1. Many cataract surgeons insist on obtaining an OCT screening for their patients before cataract surgery. Among a number of pathologies, the scan can help rule out dry AMD, evident in this patient’s finding. |

Prioritizing the Retina

Kendall Donaldson, MD, Medical Director of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Florida, may be an anterior segment surgeon, but when she’s planning surgery, she says she focuses “from the very start” on the retina. “The retinal exam is an essential component of any anterior segment surgery,” she explains. “With premium lens technology, complex optical mechanisms and high patient expectations, if we overlook even minor retinal pathology, it may yield a devastating visual outcome.”

Often, she acknowledges, patients may present with significant cataracts that not only impact their vision but also preclude detailed visualization of the posterior segment by the surgeon. “For denser cataracts, an ultrasound may provide more general information, revealing potential retinal detachments, tears or—in rare cases—tumors.”

Andrew Kao, MD, a partner at Empire Eye & Laser Center, Bakersfield, California, considers a retinal exam a priority for every surgical patient. “You never know what you’re going to find,” he says. “For example, you may discover that a patient has had a recent retinal tear or a retinal schisis.” Dr. Kao adds that patient expectations also factor into his consideration. “The expectations you communicate to the patient before the surgery can help make sure there are no surprises,” he notes.

According to Doug Grayson, MD, a cataract and glaucoma surgeon at Omni Ophthalmic Management Consultants, a multi-practice group headquartered in Iselin, New Jersey, the more complex you make your preop exam, the more you safeguard patients against untoward events and achieve the highest standards of care.

“There are many pathologies available for discovery now, especially with today’s technologies,” he says. “But if the patient has a real hard white cataract, we have to let the patient know that we can only see so much back there, documenting the conversation.1 Then, after the cataract has been removed, we may find other pathologies that we have to investigate and take care of.”

You can best avoid refractive and visual surprises if your patient benefits from a preop retinal exam that involves “clinically appropriate approaches” to identify pathologies—and a preop retinal exam that recognizes the effects that each “clinically appropriate approach” may have on the outcome of surgery, according to Dr. Charles.

“A preop exam of the retina requires the use of specific diagnostic technologies—and using them to potentially uncover overt and subtle manifestations of disease that could rule out certain types of surgery, such as a premium IOL procedure,” he says. Besides the classic suboptimal view of the retina caused by a dense cataract, he lists the following additional challenges that may need to be overcome when managing any given patient:

• insufficient training, knowledge, or emphasis on macular disease;

• fragmentation of care, resulting in separation of the preop examiner and the surgeon;

• older OCT technology;

• the distracting and arguably superfluous display designs of older or newer OCTs, potentially masking scan findings;

• inadequate interpretations of findings;

• macular holes;

• subretinal fluid without bleeding and with a small choroidal neovascularization, found in early age-related macular degeneration; and

• central serous retinopathy.

“It’s also important to keep in mind that A-scan ultrasound axial length measurements may be inaccurate in the presence of any of these conditions,” he continues. “Low coherence optical measurement from the retinal pigment epithelium is mandatory (with the use of IOLMaster, the Lenstar 900 or similar devices).”

Offering a slightly different view on one aspect of preop screening, Sara J. Haug, MD, PhD, a retinal specialist at Southwest Eye Consultants in

Durango, Colorado, believes the older, time-domain OCTs can still play a helpful role. “Sure, having the latest technology is always best,” she acknowledges. “But is it necessary for a cataract surgeon to have the latest and greatest OCT? Probably not. If they see any problems or changes, they can consider a consult with a retinal specialist.” (See “To OCT or Not to OCT Before Cataract Surgery?” below.)

To OCT or Not to OCT Before Cataract Surgery? “We don’t routinely order a macular OCT for every cataract patient,” says Andrew Kao, MD, an anterior segment surgeon and partner at Empire Eye & Laser Center, Bakersfield, California. “That would be a bit cumbersome. If we’re doing several hundred cataract consultations in a year, depending on our clinic flow, it may not be feasible to do the OCT on every patient. However, when we do premium IOLs, we routinely do get a macular OCT.” To ensure each case proceeds without surprises, Dr. Kao continues, he relies on “a very good history” for every patient. “If exam findings don’t match the level of cataracts or refractive error, a more thorough preop work-up should be done. If there is any clinical suspicion, then, yes, an OCT is appropriate.” Kendall Donaldson, MD, an anterior segment surgeon and the medical director of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Florida, typically obtains an OCT before every cataract surgery—most significantly before implanting a premium IOL, she notes.1 “A mild epiretinal membrane may easily be missed during a slit lamp exam through a significant cataract,” she says.2 “This may be a significant impediment to optimal vision if a diffractive multifocal IOL is implanted. Besides an ERM, we also need to be concerned about the possibility of a lamellar hole, a full-thickness macular hole, drusen, dry AMD, wet AMD, diabetic retinopathy, a peripheral retinal tear or a retinal detachment. To avoid these problems, perform your best slit-lamp exam (not just look at the cataract) and consider a screening macular OCT on all cataract preop patients.” Sara J. Haug, MD, PhD, a retinal specialist at Southwest Eye Consultants in Durango, Colorado, also believes anterior segment surgeons should arrange for an OCT on every patient before cataract surgery. “I think it’s pretty standard these days,” she says. “Based on the OCT image, they can determine if a retinal consult is required.” Doug Grayson, MD, a cataract and glaucoma surgeon at Omni Ophthalmic Management Consultants in Iselin, New Jersey, believes OCTs are critical to use before every cataract surgery. “The OCT could find a lamellar hole, or an epiretinal membrane, or some other pathology that’s too hard to see with direct observation,” he points out. “It could be diabetic retinopathy, or lesions that are very difficult to see without OCT.” Steve Charles, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Tennessee Hamilton Eye Institute , is another firm believer in OCT before surgery. “The presence of many critical macular diseases are simply invisible without the use of spectral domain or swept source OCT,” he says.

1. Ahmed TM, Siddiqui MAR, Hussain B. Optical coherence tomography as a diagnostic intervention before cataract surgery—a review. Eye (Lond) 2023;37:11:2176-2182. 2. Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T, et al. Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes. The Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:6:1033-40. |

Critical Preop Decisions

One central question is whether or not to refer every preop patient to a retinal specialist before anterior segment surgery. Dr. Kao says he insists on it for many cataract procedures. “Certain conditions can worsen after cataract surgery, such as diabetic retinopathy, even if the patient doesn’t have macular edema before surgery,” he says. “The inflammation from the surgery can cause swelling after the procedure. If a patient has moderate diabetic retinopathy, I want the patient to see a retinal specialist first.”2

As a retinal specialist, Dr. Haug says she prefers seeing all cataract surgery candidates preoperatively. She explains that she has “a pretty low threshold” for obtaining a fluorescein angiogram in the presence of intermediate macular degeneration or diabetes. “This prevents a postop surprise,” she points out. “The data tells us that treating early wet macular degeneration before cataract surgery, or that making sure that diabetic retinopathy is under reasonable control before the surgery—without macular edema—positively impacts cataract surgery results.3

“In these cases, I usually say, ‘Give me a couple months (before performing cataract surgery).’ I definitely want to give one or two anti-VEGF injections before we continue with cataract surgery for these patients.”

Dr. Grayson delays surgery if the patient’s visual acuity isn’t consistent with what he expects, based on his examination, and if he suspects the retina requires attention. “Even when there is a hard cataract, we may hold off,” he says. “We might refer the patient out to one of the two retinal specialists in our practice. It’s always better to get these things cleared beforehand.”

|

|

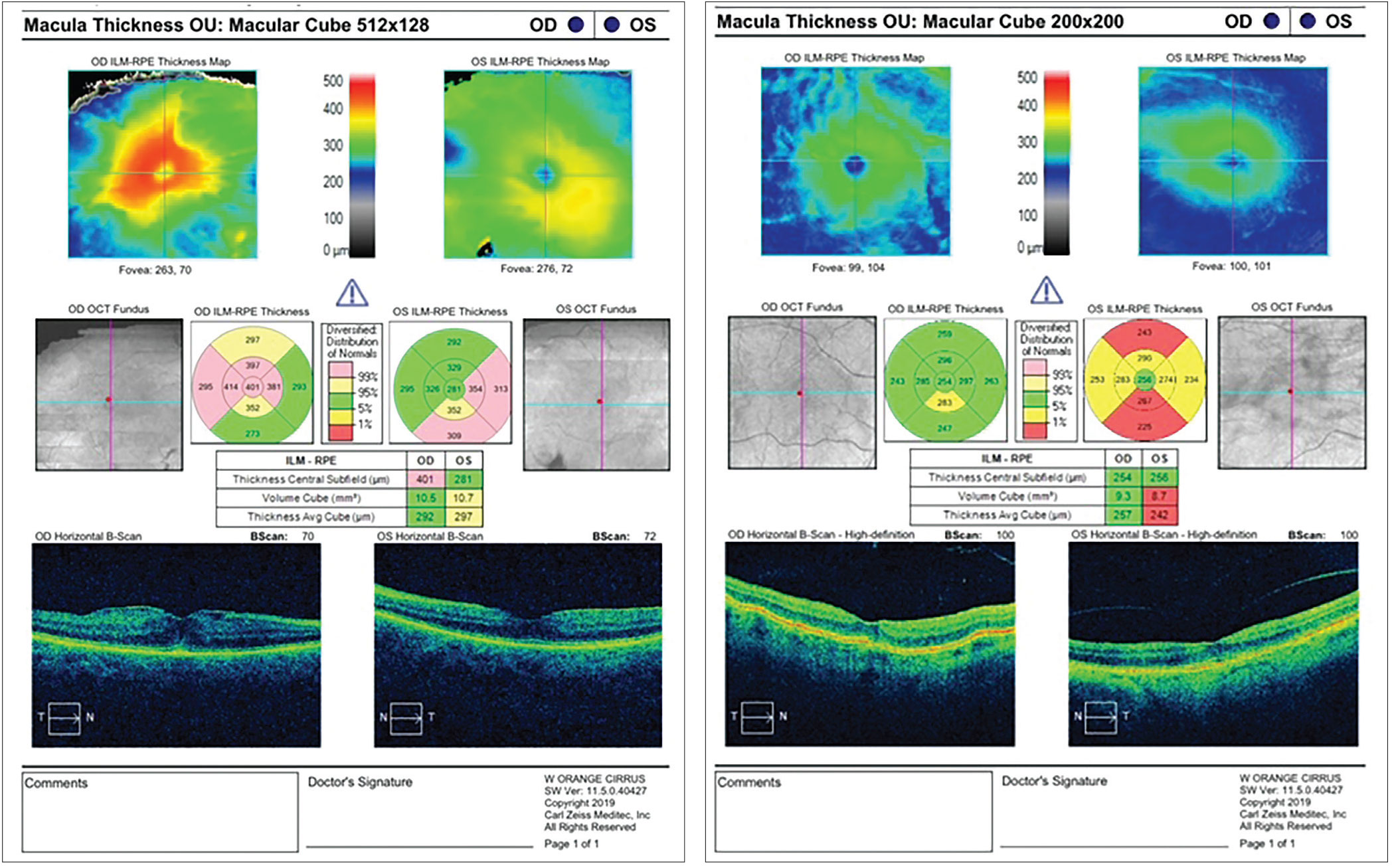

Figure 2. (Left) This patient has an epimacular membrane. Preop and postop topical NSAIDS may be a necessary treatment, as there could be a potential higher incidence of CME. Also, the surgeon should have a detailed discussion with the patient of the potential for cataract surgery to compound the issues related to the epiretinal membrane, and the possible need for retinal surgery. Figure 3. (Right) A check of the retina also may be indicated after cataract surgery. In this case, the patient has hypotonous maculopathy, possibly having occurred from a chronic wound leak or ciliary body cleft. |

In extreme hyperopes, Dr. Grayson continues, “we may have a patient with very narrow angles. You don’t want to dilate them. So you have to rely heavily on OCT and any other findings. It makes the case more challenging. You want to look at the OCT as closely as possible and compare what you find at the back of the eye to the patient’s visual acuity.”

Dr. Donaldson refers a patient to a retinal specialist before surgery for two primary reasons: “Number one, if I’m making a new retinal diagnosis that requires treatment before I can safely proceed with surgery, such as a retinal detachment or a diabetic vitreous hemorrhage, and number two, if I’m making a diagnosis of a condition that may evolve or worsen in the near future (with or without surgery). I need to make sure such a patient initiates a relationship with a retinal specialist. I’m thinking of cases when ERM that may develop fluid and evolve into CME after surgery,4 or diabetic retinopathy affecting the macula. A new diagnosis of a macular hole that may limit the postop vision is another good reason to have a retina specialist investigate first.”

In the context of these issues, Dr. Grayson adds: “The importance of documentation can’t be overstated. The thing that’s going to matter the most if your patient isn’t satisfied with your surgery—for whatever reason—is what you’ve put in the chart.”

How to Apply Technologies

Dr. Charles emphasizes judicious use of today’s technologies, noting that “the pseudo-color algorithms, thickness maps, and three-dimensional renderings that are featured by some of today’s OCT devices can hide crucial pathology. Also, the photographer or technician may select a single image for the electronic medical record, and that’s also very bad. The surgeon should look at all B-scan OCT slices, and those images should be grayscale B-scan slices.”

Screening should be completed with a 78 D-to-90 D lens, using an optimal optical view and a plano fundus contact lens with anti-reflective coating, he continues. “I believe angiography is rarely needed—and in fact never needed for pre-phaco screening,” he adds. “Also, Optos wide-angle imaging has insufficient resolution for a macular evaluation. And blue light auto-fluorescence is optimal for geographic atrophy in AMD and previous cases of central serous retinopathy.”

Dr. Charles adds: “The presence of many, large, placoid, confluent drusen poses a much greater risk of AMD than do a few fine drusen. Also, macular drusen are considered much more of a significant risk factor than extra-macular drusen. Finally, as demonstrated by the AREDS data, cataract surgery has not been found to cause AMD progression.”5

He continues: “CME prevention and treatment strategies don’t need to be modified for AMD, DME or epimacular membrane patients,” he continues. “The definition of high CME risk should be reserved for patients with uveitis, such as pars planitis or sarcoid uveitis. And remember that wet AMD and vitreomacular traction syndrome are very common. AMD and VMT, though unrelated, must both be treated—AMD with an anti-VEGF agent and VMT with pars plana vitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling, not ocriplasmin (Jetrea).”

Premium IOL Considerations

Most surgeons agree that implantation of premium IOLs is a primary challenge to the retina in many cases. Multifocal IOLs decrease contrast sensitivity and should therefore be avoided in most patients with any macular disease, including patients with significant drusen (intermediate, placoid), hyperpigmentation, and wet AMD, observes Dr. Charles.

But Dr. Grayson takes a different approach here, employing a guarantee to his patients that enables him to avoid patient dissatisfaction with multifocals that can arise because of macular or retinal issues. “You have to exchange a premium IOL if it doesn’t work out—unless you’re going to cause more of a complication by exchanging it,” he says. “And you have to explain this to the patient.”

Dr. Grayson typically avoids offering absolute solutions to patients with retinal pathology. “You can’t just group all the multifocals together,’ says Dr. Grayson. “Each has different characteristics and different tolerances for retinal conditions. Patients, for different reasons, such as occupational or preference for less spectacle dependence, etc., have varied needs, despite which pathologies we might tell them exist. I generally say that bad macular degeneration, bad glaucoma, bad epimacular membrane and other nerve pathologies are contraindications for any type of multifocal lens. However, the so-called bad pathologies can come in gradations. Certainly we have implanted multifocals in patients with glaucoma who have arcuate defects but don’t have severe glaucoma. Occasionally, we have implanted multifocals in patients with severe glaucoma and advanced superior arcuate scotomas, if we are using the more forgiving IOL, such as an extended-depth-of-field, like the Symfony.”

Dr. Donaldson, on the other hand, takes a “very conservative approach” to premium IOLs. “I generally rule out any patient with macular pathology when considering a multifocal IOL,” she says. “Even if the macular pathology is relatively mild, a multifocal lens may amplify it significantly, affecting vision. I would much rather implant a monofocal or monofocal-plus lens and target for some degree of monovision, if the patient desires more spectacle freedom.”

She remains ever mindful that patients have very high expectations for their vision following cataract surgery. “Screening for retinal pathology, corneal pathology, ocular surface disease and other pre-existing conditions is paramount to making the best decisions as we counsel our patients before surgery,” says Dr. Donaldson. “This lets us achieve our best outcomes and sets reasonable patient expectations to avoid disappointments postoperatively.”

|

|

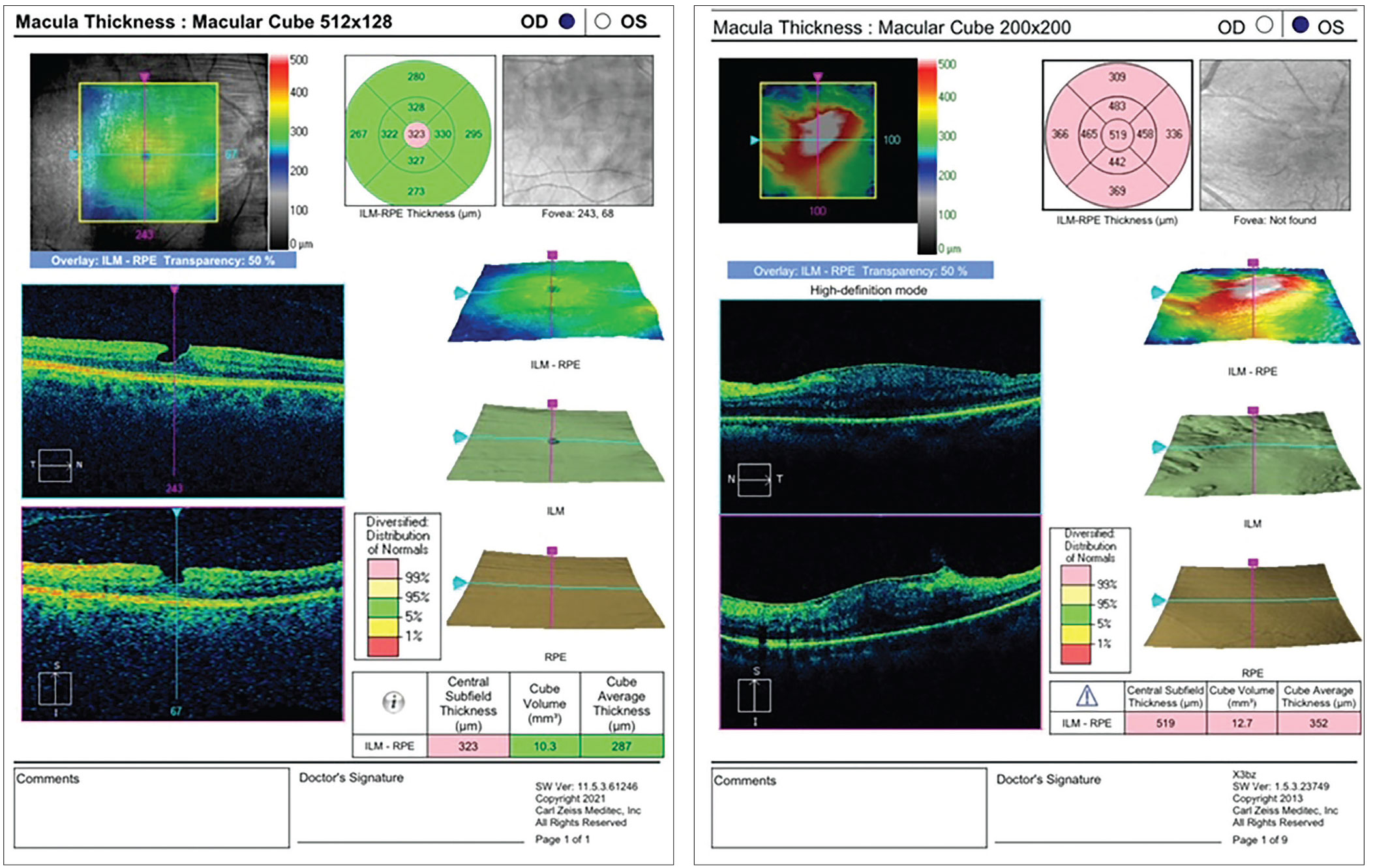

Figure 4. (Left) A lamellar hole, such as the one found in this patient, may be a relative contraindication to implantation of a diffractive multifocal IOL, and can significantly affect vision if the patient insists on giving the lens a try. The patient may need the hole closed prior to cataract surgery and should be informed that the cataract alone may not be the etiology causing decreased vision. Figure 5. (Right) Retinal pigment epithelium and glial cells can proliferate along the surface of the inner limiting membrane, resulting in premacular gliosis, which can sometimes be exacerbated by cataract surgery, as shown in this image. |

Dr. Charles emphasizes the importance of forecasting the effects of retinal pathology that will likely develop after any anterior segment surgery. “Remember, for example, that the frequency of geographic atrophy and neovascular AMD increases with each decade of a patient’s life,” he says. “Use of a multifocal IOL in a healthy 55-year-old with intermediate macular drusen is not a good plan.”6

When preparing to implant a multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus lens, Dr. Kao says he uses “careful counseling” in a patient with concerning retinal pathology. “The patient may not have the best quality vision after surgery,” he adds.

When Refractive Surgery Is Planned

Specialists report that evaluating patients before refractive surgery isn’t as challenging. “One of the biggest issues is that some of these patients are high myopes,” says Dr. Kao. “You want to be really careful and look for retinal pathology, such as a retinal tear or lattice degeneration. We will have a retina specialist take a look. The specialist can determine if the patient needs to be lasered—before we do LASIK or a refractive lens exchange. This will ensure that we’re not dealing with a retinal tear or something along those lines after surgery.”

Dr. Haug agrees with this precaution from her retinal specialist perspective. “High myopes are more likely to have some of these peripheral retinal changes,” she says. “It’s a low likelihood, but higher than your average person for developing a tear or detachment. I think it’s important to do a really good peripheral exam on those patients and treat anything you see that could lead to problems down the road. Myopic degeneration is also important to watch for, but it’s fairly obvious when it appears, even during a fundus exam.” She points out that refractive surgery patients are typically young, without much macular pathology. “I would imagine that some refractive surgery surgeons are giving preop OCTs, but it’s probably less critical to do so.”

For corneal refractive surgery, such as LASIK, PRK or SMILE, Dr.

Donaldson says her team always does a dilated exam. “Macular OCTs are not the standard of care,” she says. “However if we note an abnormality of the retina or nerve during our exam, we would proceed to the next step with imaging or we would arrange for a consultation with an appropriate specialist,” she says. “For patients with high myopia (over -7 D or so), we often refer to a retinal specialist for clearance, especially if the patient has lattice degeneration with or without holes, or tears in the retinal periphery.”

Final Analysis

Given the complexity of pathologies now discoverable in the retina, all specialists agree that a cookbook approach isn’t possible.

“Nothing is that straightforward in cataract or refractive surgery,” Dr. Kao is quick to point out. “Challenges arise when a patient has had trauma or uveitis in the past, for example. It can be difficult to do a posterior exam on these patients. Another challenge is when the pupil is small or scarred down, or when we encounter a patient with a hard brunescent nucleus.”

Dr. Grayson ultimately believes it’s up to the surgeon’s procedural skills and patient management efforts to steer clear of significant difficulty. “It’s hard to imagine today that you would be doing cataract surgery on anyone without becoming aware of the retinal issues,’’ he says. “There are so many different ways you can determine whether or not the retina might also have an issue.”

Dr. Charles has a consulting relationship with Alcon. Dr. Haug has a consulting relationship with Genentech. Dr. Donaldson is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision, Bausch + Lomb, Alcon and Zeiss. Dr. Kao is a consultant and speaker for Glaukos. Dr. Grayson has no related financial disclosures.

1. Scanlan D, Siddiqui F, Perry G, Hutnik CML. Informed consent for cataract surgery: What patients do and do not understand. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:10:1904-12

2. McKeague M, Sharma P, Ho AC. Evaluation of the macula prior to cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018;29:1:4-8.

3. Baek J, Lee MY, Kim M, et al. Ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography findings in patients with macular edema following cataract surgery. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019;3:29:610-614.

4. Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T, et al. Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes. The Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:6:1033-40.

5. Chang JR, Koo E, Agron E, et al. Risk factors associated with incident cataracts and cataract surgery in the Age-related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): AREDS report number 32. Ophthalmology 2011; 118:11:2113-9.

6. Farooghian F, Agron E, Clemmons TE, et al. Visual acuity outcomes after cataract surgery in patients with age-related macular degeneration: Age-related eye disease study report no. 27. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;116:11:2093-100.