Cyclodialysis clefts occur when the longitudinal ciliary muscle fibers separate from the scleral spur,1 forming a pathway from the anterior chamber to the suprachoroidal space. The subsequent increased uveoscleral outflow may result in hypotony maculopathy and other sequelae such as anterior chamber shallowing, choroidal effusions, retinal folds and vision loss.2

Cyclodialysis clefts can arise as a complication of any minimally invasive glaucoma surgery, but they’re most likely to occur with goniotomy. Fortunately, this is rare. A review of the FDA’s MAUDE database3 found 30 case reports of clefts associated with Cypass (which is now off the market), iStent and Xen over a 10-year span, which is a very small number considering the thousands of MIGS surgeries performed every year.

Here, I’ll discuss how to avoid cyclodialysis clefts with MIGS, as well as the non-surgical and surgical approaches to repair.

Preoperative Considerations

To minimize the chances of this complication occurring, identify patients who may be at higher risk. Risk factors include patients with a suboptimal gonioscopic view (e.g., due to corneal opacities, edema, arcus or scarring); patients with very lightly pigmented trabecular meshwork whose angle anatomy may be misidentified; and uncooperative patients, such as those who might cough or jerk their head suddenly in the middle of surgery.

Intraoperative Considerations

The right tools and tricks can make a difference. Here are three intraoperative strategies that can help:

• For eyes with lightly pigmented trabecular meshwork, consider using trypan blue to stain the tissue. Trypan blue is readily available and easy to incorporate into the surgery.

• Consider a retrobulbar block in a patient who’s uncooperative to get complete akinesia of the eye and decrease the risk of a movement-related complication.

• Novice surgeons who may not have as much experience using intraoperative gonioscopy may press down too hard on the eye with their off hand, creating corneal striae that impede the view of the angle, subsequently increasing the risk for a complication. If you’re training a resident, consider using a hands-free gonio lens that couples itself with the corneal surface such as the Ocular SecureFlex HF Surgical Gonio. Another option is the Transcend Vold Gonio (Volk) which is designed to have the goniolens float freely on the corneal surface, so even if the surgeon is pressing down on the eye, the gonio lens won’t compress the cornea and cause corneal striae.

Non-surgical Management

If the cleft is small (less than one clock hour), the management decision is pretty easy: Most surgeons will opt to observe. If left alone, a cleft of this size will probably close on its own. Spending extra time in the operating room to perform a primary closure is usually unnecessary.

Here are some options to consider for encouraging spontaneous closure:

• Reduce the amount of postoperative steroid. This allows some more inflammation in the eye.

• Administer topical atropine drops once or twice daily for several weeks. Atropine drops will dilate the pupil and relax the ciliary muscle, making it more likely that the ciliary muscle will be in close proximity to the scleral wall.

• Laser the cleft using a diode laser. This produces some inflammation to encourage closure. Use higher power, large spot size and long duration. Suggested power settings for 100 spots in overlapping rows: 700 to 900 mW, 200-µm spot size, 500 milliseconds duration.

Surgeons may differ in their approach for larger clefts. For a cleft that’s two clock hours or more, some may choose to close it primarily and others may elect to give the cleft a chance to close on its own before taking the patient back the operating room. In general, larger cleft size is a preoperative risk factor for spontaneous closure failure.4

Timing of Surgical Repair

Permanent visual acuity decrease from hypotony maculopathy may occur without timely intervention. So, how long should you wait before heading to the operating room? It’s a tricky question. The general recommendation is to intervene within the first three months—perhaps give the cleft a month and a half to close on its own, and if it hasn’t by then, make plans to return to the operating room.

This three-month recommendation comes from a small study of nine patients who had hypotony maculopathy after trabeculectomy.5 Six eyes had vision restored after undergoing surgery to elevate the IOP. Three eyes didn’t return to preoperative vision; these eyes all had hypotony for more than three and a half months.

However, there are documented cases of vision being restored with surgical repair even years after hypotony. In one report of 32 eyes, postoperative visual acuities were significantly better than preoperative acuities, even when surgical repair was done 54 months after trauma.6 This same study noted that mean IOP was 3.2 mmHg regardless of cleft size, and that larger clefts took longer for postoperative elevated IOP to normalize after direct cycloplexy.

Nevertheless, we can’t know which eyes will recover vision and which won’t, so timely surgical repair is advised.

Surgical Repair Techniques

Here are four approaches to consider:

• “Bucket Handle” docking technique. This technique requires that the patient be pseudophakic. It’s suitable for small- to moderate-sized cyclodialysis clefts and involves mostly internal closure with some minor external dissection.

|

|

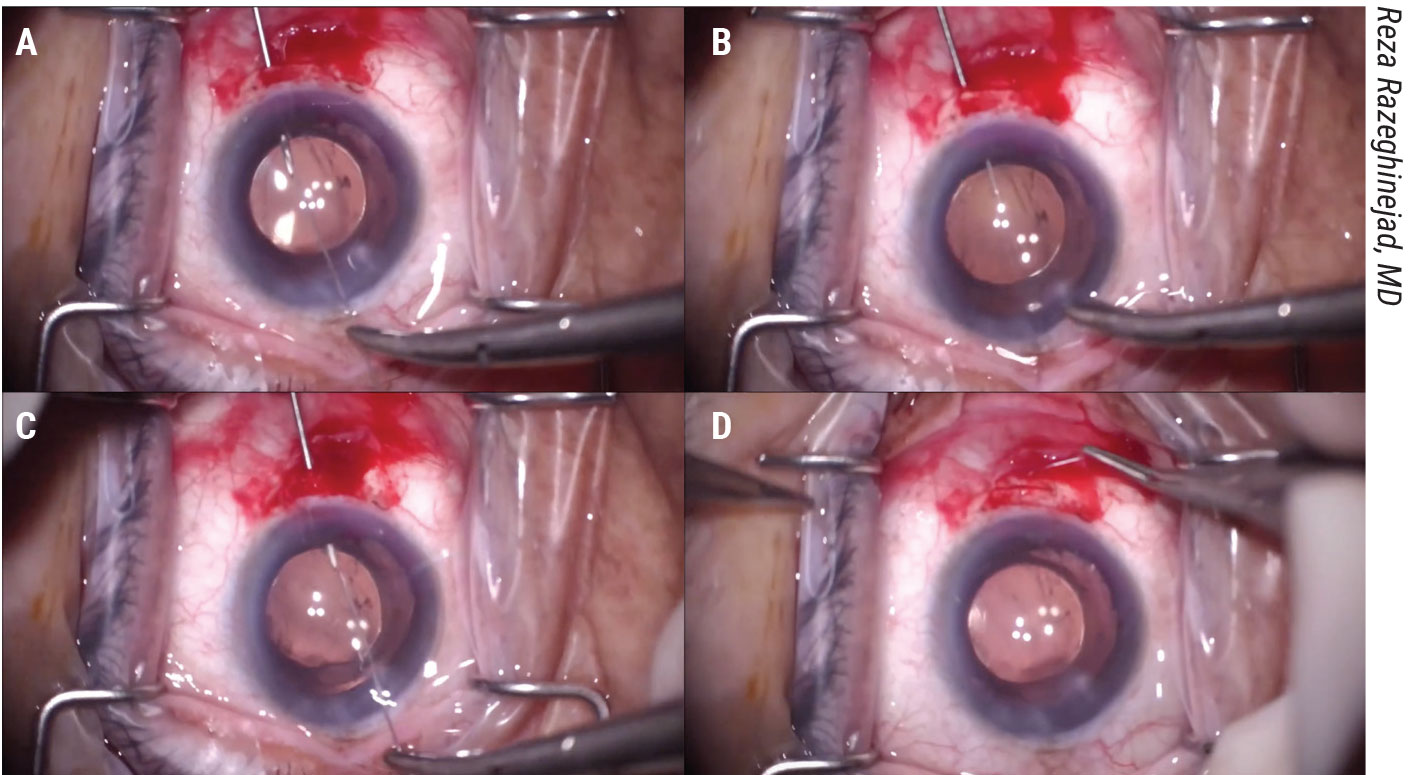

Figure 1. In the “Bucket Handle” closure demonstrated by Reza Razeghinejad, MD, a 27-ga. needle is passed through a scleral groove 1.5 mm posterior to the limbus under a peritomy which passes into the ciliary sulcus and docks with the long straight needle of a Prolene suture passed across the anterior chamber through a clear cornea wound. This is repeated with the other end of the Prolene. Tying reapproximates the ciliary body and buries the knot in the groove. View the video at https://youtu.be/3cuw2vDV05U. |

First, make a conjunctival dissection. Then, carve a partial thickness scleral groove parallel to the limbus and 1.5 mm posterior to the limbus. Make a clear corneal incision opposite the scleral groove and fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic. Next, pass a 27-ga. hypodermic needle through the scleral groove into the ciliary sulcus just past the outer extent of the cyclodialysis cleft. Then, pass the long straight needle of a double armed Prolene suture across the anterior chamber through the clear cornea wound and dock it with the 27-ga. hypodermic needle (Figure 1A).

Withdraw the 27-ga. needle, bringing the long needle and Prolene suture along with it (Figure 1B). Repeat this docking technique with the other needle of the double-armed Prolene suture on the opposite side of the cyclodialysis cleft (Figure 1C).

Tying the suture reapproximates the ciliary body to the scleral wall and buries the knot into the scleral groove to prevent erosion. You then close the conjunctiva (Figure 1D).

• Modified Cionni ring closure. This capsular tension ring-assisted technique also requires that the patient be pseudophakic. It’s suitable for large cyclodialysis clefts and involves mostly internal closure with some minor external dissection.

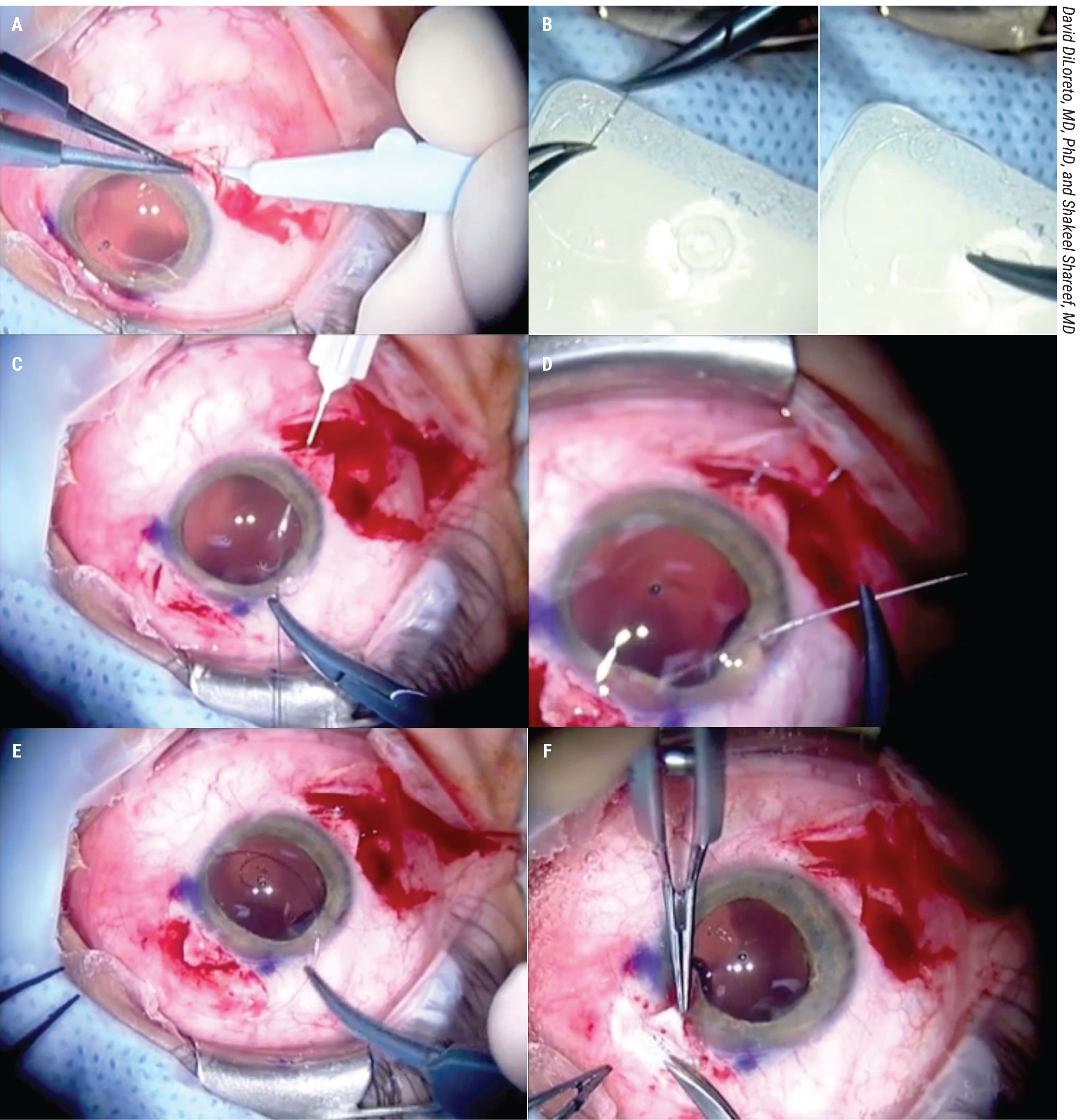

First, open the conjunctiva in two sections 180 degrees apart. Create partial thickness scleral flaps 180 degrees apart (Figure 2A). Then, pass the Prolene suture into both eyelets of the Cionni ring and tie them to the eyelets (Figure 2B).

Dock the long straight needles of the Prolene suture into the 27-ga. hypodermics passed into the sulcus under the scleral flaps. This is repeated with both needles of the double-armed Prolene (Figure 2C).

Perform this docking procedure 180 degrees away under the second scleral flap for the Prolene suture that was tied to the second eyelet of the modified Cionni ring (Figure 2D). Then, tuck the modified Cionni ring into the ciliary sulcus (Figure 2E).

You can then tie the sutures with the knots buried under the scleral flaps to prevent erosion (Figure 2F). This gives a circumferential tension with the ring allowing for closure of very large cyclodialysis clefts.

|

|

Figure 2. In this CTR-assisted closure for large clefts, David DiLoreto, MD, PhD, and Shakeel Shareef, MD, use a modified Cionni ring. You first create scleral flaps 180 degrees apart. Then, pass the Prolene suture into the eyelet and tie it to the eyelet. Dock the long straight needles into the 27-ga. hypodermics passed into the sulcus under the scleral flaps. This is repeated with the other eyelet. Then, carefully tuck the ring into the ciliary sulcus. You can then tie the sutures, providing circumferential tension from the ring, and allowing for closure of very large clefts. |

• Ab interno closure without docking. This technique is suitable for phakic patients. It’s good for small cyclodialysis clefts and involves mostly internal closure with some minor external dissection. Some peripheral anterior synechiae and corectopia will be created.

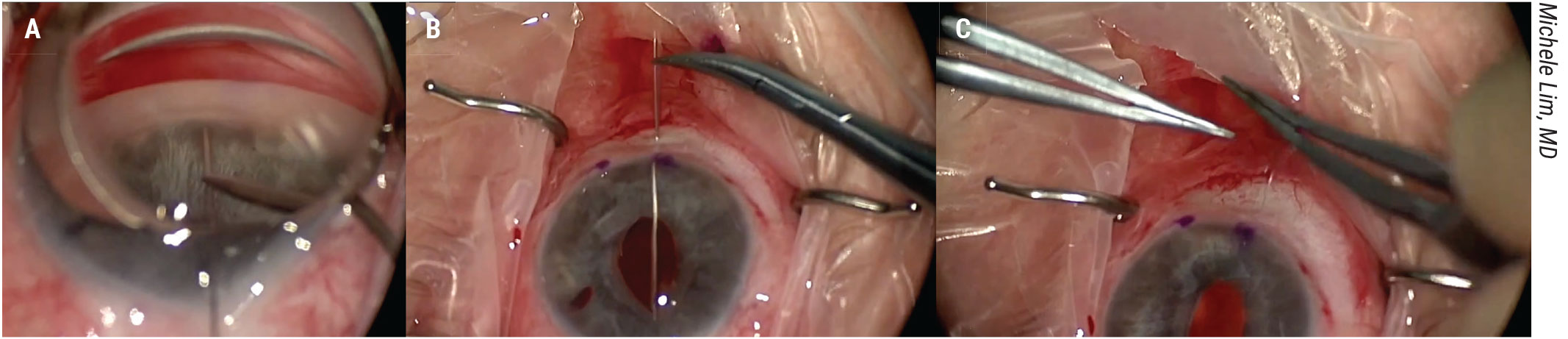

First, open the conjunctiva, create a clear corneal incision and fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic. Pass a long needle of a Prolene suture across the anterior chamber, piercing through far peripheral iris and through the anterior chamber angle (Figure 3A).

Bring the needle out through the sclera. Repeat this process with the second needle of the double-armed Prolene suture (Figure 3B). Tie the suture and bury the knot (Figure 3C). Finally, close the conjunctiva.

|

|

Figure 3. This ab-interno closure procedure demonstrated by Michele Lim, MD, doesn’t involve docking. A long needle of a Prolene suture is passed across the anterior chamber, piercing the far peripheral iris and angle. The needle is passed out through the sclera. This is repeated with the second needle of the double-armed Prolene suture. The suture is tied and the knot is buried. View the video at https://youtu.be/CuEMcgzdV_0. |

• Ab externo direct closure. This technique is also suitable for phakic patients. It requires a large conjunctival dissection and scleral flap dissection. It’s especially helpful if the cyclodialysis cleft is difficult to visualize.

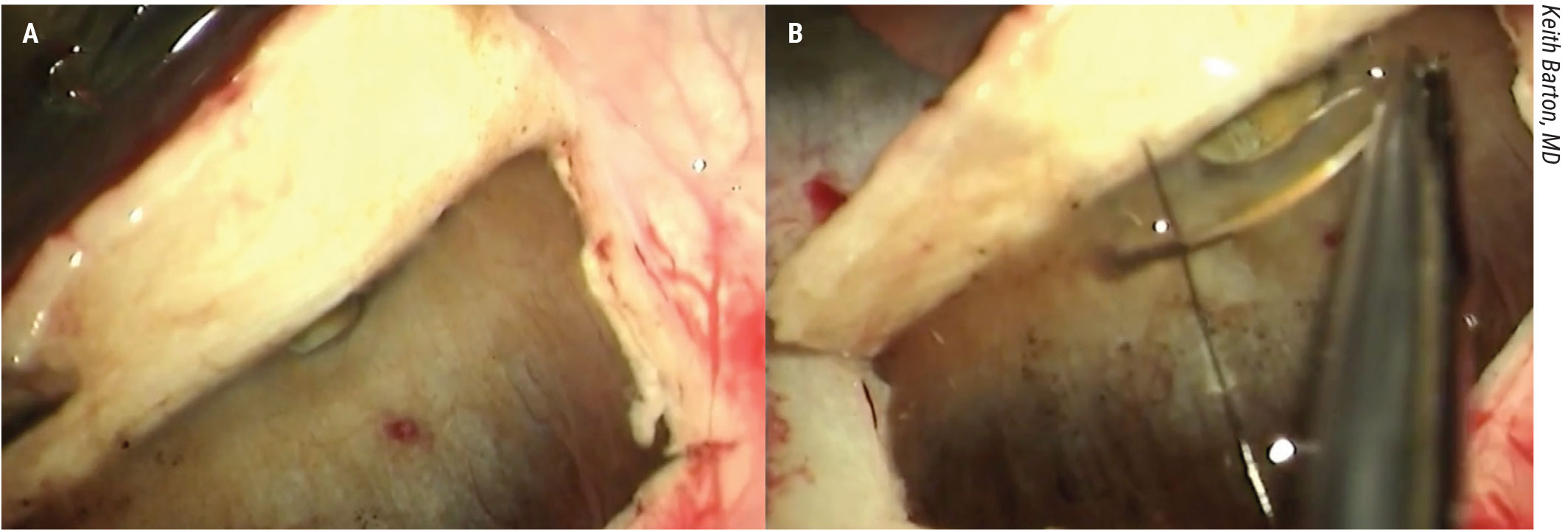

First, a full thickness scleral flap is created. Lifting it reveals the area of the cyclodialysis cleft (Figure 4A). Suture is passed through the scleral flap and across the tissue posterior to the defect and tied, closing the defect (Figure 4B). The scleral flap and conjunctiva are then closed.

|

|

Figure 4. In this ab-externo direct closure through a full thickness scleral flap demonstrated by Keith Barton, MD, there’s unimpeded flow of aqueous through the suprachoroidal space. The surgeon identifies the cleft under the scleral flap and closes it under direct visualization with 9-0 nylon. |

Postoperative Patient Counseling

Once the cleft is closed, it takes about 24 to 48 hours for the body’s natural outflow system to reset itself. During this time, the patient’s IOP may increase to pressures as high as 50 or 60 mmHg. Glaucoma drops are used to bring down the pressure during this period.

It’s very important to warn patients that there’s a high chance that successful closure of the cleft may be accompanied by a dramatic and often painful IOP elevation. This IOP elevation is usually self-limited but may rarely require filtering surgery. It’s thought that the longer a patient has had a cyclodialysis cleft and therefore a non-functional outflow pathway, the longer the eye will take to normalize.

In summary, cyclodialysis clefts with MIGS are rare. We can take proactive steps to prevent them from happening. Waiting a few months and applying diode laser for spontaneous closure is reasonable. Plan to return to the OR for closure within three months of onset, and be sure to prepare the patient for a postoperative IOP spike.

Dr. Kim is in private practice with Eye Doctors of Washington in the D.C. area. He has no related financial disclosures.

1. Ioannidis AS, Barton K. Cyclodialysis cleft: Causes and repair. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2010;21:2:150-154.

2. Agrawal P, Shah P. Long-term outcomes following the surgical repair of traumatic cyclodialysis clefts. Eye 2013;27:1347.

3. Duong A, et al. Adverse events associated with microinvasive glaucoma surgery reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Opthhalmol Glaucoma 2021;4:433-435.

4. Ioannidis A et al. The evaluation and surgical management of cyclodialysis clefts that have failed to respond to conservative management. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2014;0:1.

5. Cohen S, Flynn H, Palmberg P, Gass D, Grajewski A. Treatment of hypotony maculopathy after trabeculectomy. Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers & Imaging 1995;26:435.

6. Hwang J, Ahh K, Kim C, Park K, Kee C. Ultrasonic biomicroscopic evaluation of cyclodialysis before and after direct cyclopexy. Archives of Ophthalmology 2008;126:9:1222.