Workup, Diagnosis and Treatment

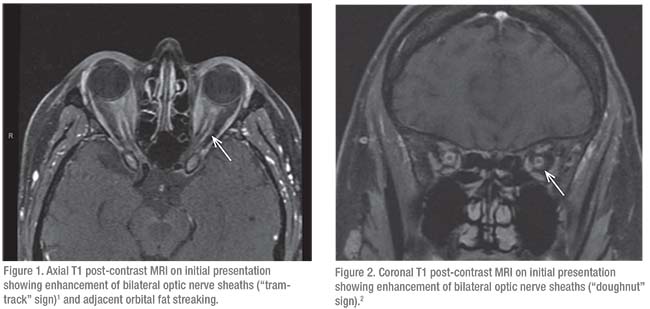

Initial serologic evaluation for potential causes of bilateral optic nerve edema included QuantiFERON-TB Gold for tuberculosis and RPR/FTA-ABS for syphilis, both of which were negative. Angiotensin converting enzyme levels were within normal limits. Lyme disease antibodies were non-reactive. Complete blood count, basic metabolic panel and liver function tests were unremarkable. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated to 79 mm/hr (normal: 0 to 29 mm/hr). Lumbar puncture was performed with an opening pressure of 22 cm H2O. Cerebrospinal fluid was colorless with 16 red blood cells and two white blood cells. There was an absence of oligoclonal bands. Infectious PCR panels, gram stain and CSF culture were negative, as was cytology. MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast revealed enhancement of bilateral optic discs and optic nerve sheaths (Figures 1 and 2). A partially empty sella was also noted. MRV was unremarkable.

|

Following the initial workup, the patient was diagnosed with bilateral optic perineuritis. She was admitted and started on intravenous methyl-prednisolone. Concurrently, her clinical trial medications (pembrolizumab with or without talimogene laherparepvec) were discontinued. After these interventions, the patient noted subjective improvement in her visual acuity and pain. She was discharged on a tapered regimen of oral prednisone.

At a one-month follow-up appointment in the Neuro-ophthalmology Service, visual acuity was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. Color plates remained full. There was no rAPD. Over the course of three

|

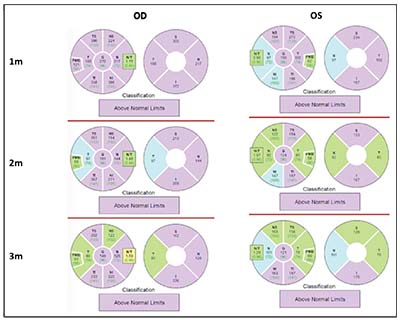

| Figure 3. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness reports showing bilateral elevation of the optic nerves one month following initial presentation and initiation of steroids. |

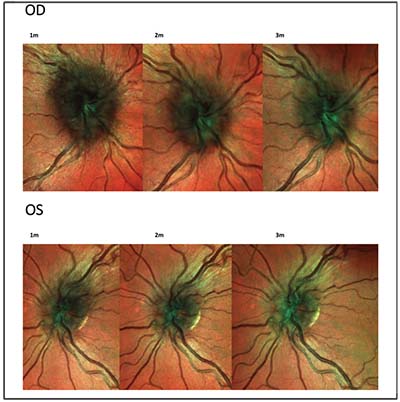

months of follow-up, she continued to report an overall subjective improvement in vision, but noted some rebound discomfort with extraocular movements accompanying each steroid taper. Spectral-domain OCT revealed thickening of the retinal nerve fiber layer bilaterally (Figures 3 and 4). Over the course of follow-up, there was notable improvement in RNFL thickness bilaterally (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

Bilateral optic disc edema has a broad differential that includes increased intracranial pressure as well as paraneoplastic optic neuropathies, both of which warrant special consideration in patients with known metastatic malignancy. Additionally, physicians must be cognizant that the mechanisms of action of the systemic immunotherapies used to treat various malignancies can themselves lead to far-reaching immune dysregulation impacting various organs, including the globe, orbit and optic nerve.1-3

In the case of our patient, early use of MRI imaging of the brain and orbits and magnetic resonance venography enabled an evaluation for metastatic space-occupying lesions and venous thrombosis, and also a

|

| Figure 4. Spectral-domain OCT multicolor imaging of the right and left optic nerves, revealing bilateral edema of the retinal nerve fiber layer one, two and three months after initial presentation and initiation of steroids. |

llowed for visualization of intra-orbital optic nerve inflammation. In our patient’s case, MRI narrowed our differential diagnosis based on the characteristic MRI findings consistent with optic perineuritis, namely the “doughnut” and “tram-track” signs on axial and coronal T1 post-contrast images.4,5

Optic perineuritis is a rare form of optic nerve sheath inflammation that is a part of the orbital inflammatory disease spectrum.4 Secondary causes of optic perineuritis include infections such as syphilis, Lyme disease, tuberculosis and herpes zoster, as well as inflammatory conditions such as granulomatosis with polyangitis, giant cell arteritis, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease and Behcet’s disease.6-12 Despite the diversity of secondary causes of optic perineuritis, the majority of cases ultimately have a negative workup and are considered idiopathic.

In our patient’s case, the timing of her symptom onset and resolution corresponded to exposure to pembrolizumab and/or talimogene laherparepvec. Pembrolizumab is an anti-PD1 antibody, which is a part of the broader class of medications referred to as immune checkpoint inhibitors. Broadly speaking, ICIs disrupt tolerance-inducing checkpoints that would normally function to inhibit T-cells from attacking host tissues. Such inhibition is strategic with respect to targeting tumors, as malignant cells utilize immune-escape strategies to evade being targeted by the immune system. Despite the clear advantages associated with enhancing the immune system’s ability to eradicate cancer cells, this approach has been associated with a class of complications known as immune-related adverse events.2 In a recent review of the existing literature on this topic, the incidence of irAEs secondary to a single ICI was estimated at 15 to 90 percent, but notably only 0.5 to 13 percent were severe enough to require ICI discontinuation.13 The incidence of ocular irAEs was <1 percent.14

Importantly, like many patients with advanced metastatic melanoma, our patient had been exposed to multiple ICIs, namely pembrolizumab at the time of presentation and ipilimumab approximately one year prior. Though individual ICIs have been associated with various ocular irAEs, there is potential for a synergistic, potentiating effect on immune dysregulation with exposure to multiple ICIs with differing mechanisms of action. Furthermore, as our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial comparing pembrolizumab and placebo versus pembrolizumab and talimogene laherparepvec, we must consider the potential impact of talimogene laherparepvec on overall immune activation. Importantly, talimogene laherparepvec is a genetically modified HSV-1 oncolytic virus, which has been hypothesized to target tumor cells by both direct destruction and by enhanced immune response secondary to a shift in the proportion of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells.15

Though our patient’s exposure to multiple systemic immune-dysregulating medications prior to and at the time of presentation suggests a role for iatrogenic inflammation secondary to a loss of immune tolerance, we must also consider the possibility of idiopathic optic perineuritis, as this remains the most common cause. Furthermore, though symptoms and examination findings improved with discontinuation of immune modulating agents, this intervention coincided with the initiation of corticosteroids, which are known to cause a dramatic resolution of idiopathic optic perineuritis.4 Regardless, we believe this case highlights special considerations in the evaluation of bilateral optic nerve edema in the setting of known malignancy and adds to the evolving body of literature detailing the diverse secondary effects of strategic systemic immune dysregulation. REVIEW

1. Papavasileiou E, Prasad S, Freitag SK, et al. Ipilimumab-induced ocular and orbital inflammation-—A case series and review of the literature. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2016;24:2:140-6.

2. Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: A comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer 2016;54:139-48.

3. de Velasco G, Bermas B, Choueiri TK. Autoimmune arthropathy and uveitis as complications of programmed death 1 inhibitor treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2:556-7.

4. Purvin V, Kawasaki A, Jacobson DM. Optic perineuritis: Clinical and radiographic features. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:9:1299-306.

5. Fay AM, Kane SA, Kazim M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of optic perineuritis. J Neuroophthalmol 1997;17:4:247-9.

6. O’Connell K, Marnane M, McGuigan C. Bilateral ocular perineuritis as the presenting feature of acute syphilis infection. J Neurol 2012;259:1:191-2.

7. Elamin M, Alderazi Y, Mullins G, et al. Perineuritis in acute lyme neuroborreliosis. Muscle Nerve 2009;39:6:851-4.

8. McClelland C, Zaveri M, Walsh R, et al. Optic perineuritis as the presenting feature of Crohn disease. J Neuroophthalmol 2012;32:4:345-7.

9. Ryu WY, Kim JS. Optic perineuritis simultaneously associated with active pulmonary tuberculosis without intraocular tuberculosis. Int J Ophthalmol 2017;10:9:1477-1478.

10. Purvin V, Kawasaki A. Optic perineuritis secondary to Wegener’s granulomatosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009;37:7:712-7.

11. Morotti A, Liberini P, Padovani A. Bilateral optic perineuritis as the presenting feature of giant cell arteritis. BMJ Case Rep. Jan 29, 2013. pii: bcr2011007959.

12. Yu-Wai-Man, P. Optic perineuritis as a rare initial presentation of sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;35:7:682-4.

13. Kang SJ, Zhang Q, Patel SR, et al. In vivo high-frequency contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of choroidal melanoma in rabbits: Imaging features and histopathologic correlations. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:7:929-33.

14. Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:49.

15. Bommareddy PK, Patel A, Hossain S, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) and other oncolytic viruses for the treatment of melanoma. Am J Clin Dermatol 2017;18:1:1-15.