Techniques for mixing and matching intraocular lenses have been around for several years now. Experts say these lens pairings have continued to evolve as IOL technology gets more advanced. “In an ideal world,” says Kendall E. Donaldson, MD, of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Florida, “we wouldn’t have to mix and match because the patient would achieve optimal quality and range of vision in the first eye and would want the second eye to be the same. However, the reality is that increased range can be accompanied by a loss in clarity and may be associated with dysphotopsias such as glare and halos. Due to this type of compromise, mixing and matching may help provide a functional range while maintaining adequate quality of vision.”

Here, cataract surgeons share their go-to lens combinations and pearls for ensuring patient satisfaction with a mix-and-match approach.

The Best of Both Worlds

Using a different lens in each eye is possible thanks to the brain’s ability to neuroadapt, explains Marjan Farid, MD, of the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute, University of California, Irvine. “The brain is an amazing computer and can take the images from each eye and combine them into one,” she says. “We’ve been taking advantage of this ability with monovision for years. Similarly, we can also mix and match different lens technologies to optimize range and quality of vision for patients.”

“Nighttime visual disturbances such as glare and halos are frequently associated with diffractive presbyopia-correcting IOLs, so mixing and matching lenses can decrease some of those visual side effects,” says Dagny Zhu, MD, of Hyperspeed LASIK (NVISION) in Rowland Heights, California. “Another reason surgeons might mix and match lenses is if the two eyes are different in terms of which lens they’re candidates for. If one eye has pathology—a significant epiretinal membrane, for example—you can typically put only a monofocal in that eye. But if the other eye is healthy, the patient could still gain some spectacle independence with a presbyopia-correcting lens in the contralateral eye. So, a different lens could be used in each eye, based on pathology and what the patient qualifies for.”

Experts say that when mixing and matching IOLs, it’s best to choose two lens models from the same platform to ensure some degree of IOL uniformity, such as the material platform, the correction for spherical aberration or whether there’s any lens tint.

“The thought is that the optics of lenses from the same platform won’t be too different, and the patient will be better able to tolerate the differences between the optical designs,” Dr. Zhu explains. She says that for some patients she likes “to mix and match within the Clareon family (Alcon) using the Vivity and the PanOptix lenses” and for others, she mixes and matches “the Symfony OptiBlue and Synergy, which are part of the Tecnis InteliLight platform (Johnson & Johnson Vision).”

Dr. Farid says she’s seen some patients in which lenses from two different companies or two different platforms were implanted. “Because of neuroadaptation, this sometimes works out very well,” she says. “However, keeping the platforms the same usually results in a better combination profile. When I mix and match lenses, I try to keep the platforms consistent between the two eyes.”

If a mix-and-match combination results in a high amount of anisometropia, patients are likely to become preoccupied with comparing one eye to the other. Mixing diffractive and refractive optics or different lens tints isn’t advisable. “If a yellow chromophore is used in the first eye, this should also be used in the second eye,” Dr. Donaldson adds.

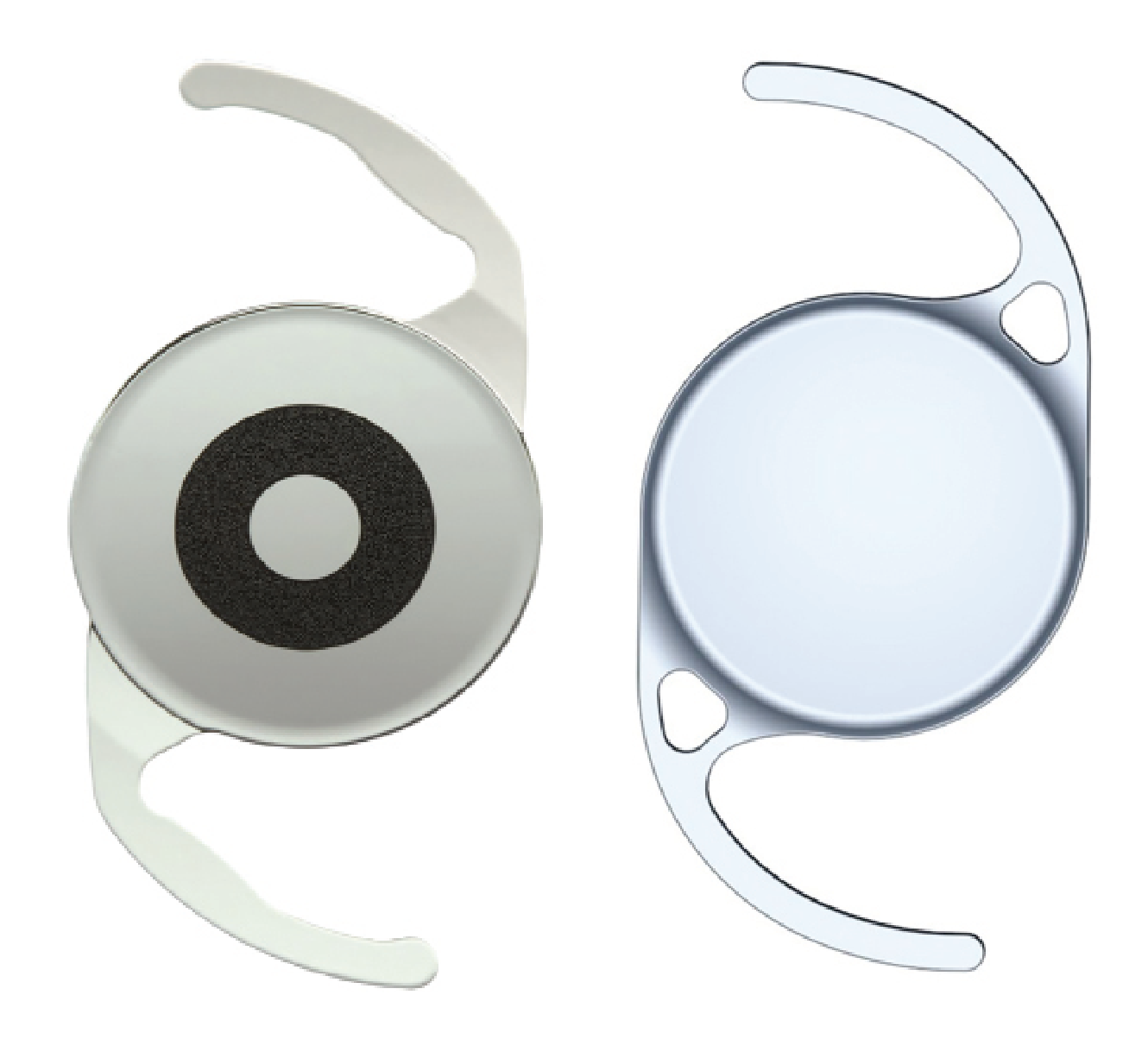

|

| The PanOptix trifocal (left) and Vivity EDOF (right) can be combined in a mix-and-match strategy to reduce dysphotopsias. (Courtesy Alcon). |

Strategies for Different Goals

Mix-and-match combinations can include monofocals, multifocals, EDOFs and other lens technologies. Here are some ways surgeons create complementary strategies to improve patients’ quality and range of vision:

• EDOFs and multifocals. Dr. Zhu says, “a common strategy I use to reduce dysphotopsias is to mix and match the Vivity and PanOptix. I place the Vivity, which is an EDOF lens, in the dominant eye, and I place the PanOptix, which is a trifocal, in the non-dominant eye. In that manner, I’ve found I’ve been able to decrease some of the nighttime halos and glare for the patient, compared to bilateral trifocal implantation, while still providing a good level of spectacle independence.

“Based on my mix-and-match data, which I presented at ASCRS this past year, close to 90 percent of my patients are still able to achieve complete spectacle independence with the Vivity-PanOptix approach,” she continues. “I’ve also found in my own data that there are far fewer complaints about significant visual disturbances with this mix-and-match combination vs. bilateral PanOptix. My younger, active patients are better able to drive at night with a mix-and-match approach.”

Mitchell C. Shultz, MD, of Shultz Chang Vision in Los Angeles, says, “I tend to use EDOF technologies in combination with trifocal technologies, making the decision [to mix and match] based on the first eye. My preference is minimizing night-vision aberrations. So, if I can achieve an excellent range of vision with an EDOF lens, then I’m likely to use it in the other eye, but if the patient isn’t satisfied with the near vision of the dominant eye with an EDOF lens, then as long as everything looks okay to support using a trifocal lens in the other eye, I’ll certainly do that to maximize range.”

One of Dr. Farid’s favorite presbyopia-correcting mix-and-match combinations is the Symfony EDOF in the dominant eye and the Synergy [a hybrid multifocal-EDOF] in the non-dominant eye. “The Symfony EDOF provides good distance and intermediate vision with a great contrast sensitivity profile,” she says. “If the patient needs more reading vision, I use the Synergy, which is also on the Tecnis platform. You do lose a little more contrast with this particular lens because it’s a multifocal optic, but it helps to maximize near vision. Patients have been very happy with this combination of lenses because they get distance, intermediate and near vision with the two eyes combined.

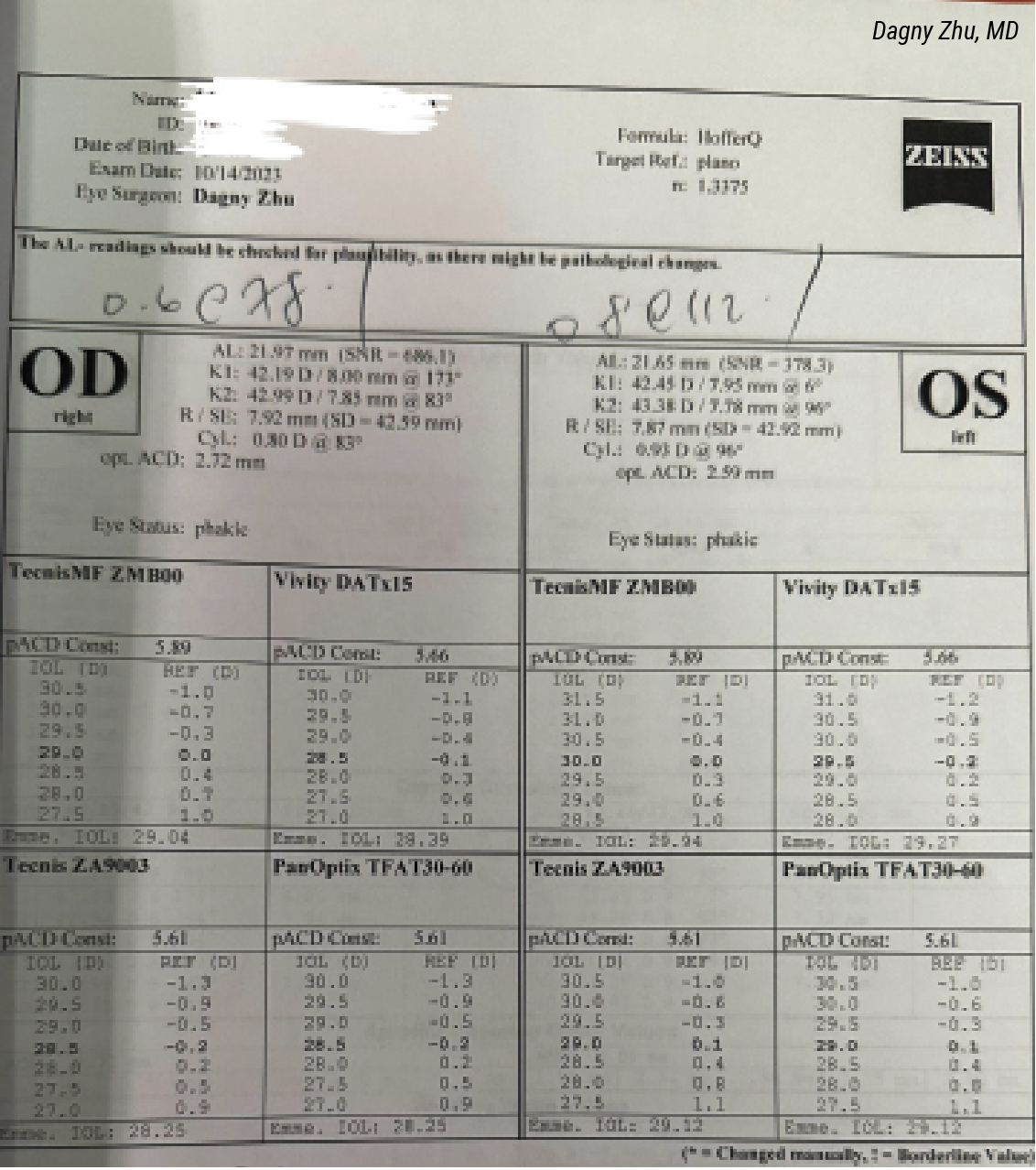

|

| This hyperopic patient initially tested left-eye dominant, but the biometry and refractive error suggested the opposite (i.e., right-eye dominant, based on longer/closer-to-normal axial length). A loose-lens trial confirmed that the patient indeed preferred the add over her left eye, and so an EDOF was placed in her right eye, and a trifocal was placed in her left eye. The patient was very happy with her final visual outcome. |

Steven H. Dewey, MD, of Colorado Springs Eye Clinic, also favors the Synergy-Symfony combination to maximize range of vision. “One of my go-to combinations is a Synergy in the non-dominant eye targeted for the least amount of hyperopia that I can target and then a Symfony in the dominant eye targeted for plano. Probably about 70 to 75 percent of my patients with a Synergy in their non-dominant eye are pleased with their range of vision. They get good distance, intermediate and reading vision.”

Dr. Dewey says that he uses this mix-and-match combination in some patients who, after receiving a Synergy lens in the first eye, notice that their distance vision isn’t necessarily as sharp as they were hoping for. “In those cases, we put the Symfony in the dominant eye to enhance distance clarity,” he says. “I had a patient a few months back who had a Synergy in her first eye. Based on our conversations, she was sure she was going to get the Synergy in her second eye as well. During the check-in between the two surgeries to confirm the plan for the second procedure, I found that between the time I had first met her and time I was doing her second surgery, she’d taken up birding. She was now a birdwatcher. And she had noticed that she wasn’t seeing the birds at the same distance that other people were seeing them. These were little birds at 50 to 60 yards away, not large birds at 10 feet. So, we put the Symfony in her second eye, and she was thrilled.”

• Monofocal combinations. “I sometimes use a monofocal lens in the distance eye of a patient, and if they do well with that and still want more range in the second eye, I’ll implant an EDOF, multifocal or trifocal in the non-dominant eye,” Dr. Farid says. “This approach requires more patient education because the patient won’t have the same degree of dysphotopsias in the monofocal eye as they will in the multifocal eye. As long as they understand that the night vision and degree of glare in the two eyes will be different, then I’m okay using this combination as well.”

An epiretinal membrane or some kind of macular pathology in one eye but not the other eye can also be grounds for a mix-and-match strategy with a monofocal. “It’s important to think about quality of vision first whenever an eye has a compromised visual pathway,” says Dr. Shultz. He adds that it’s also important to explain to patients that “sometimes we’ll stick with a monofocal or monofocal toric, or even an EDOF. I think with Vivity, it’s sometimes safe to place it in an eye that may have a mild epiretinal membrane, but the other eye is okay. We can use technology that achieves the patient’s visual demands in that respect, so we may choose to use a PanOptix lens in the second eye to give them that range they’re looking for.”

• Small-aperture combinations. The Apthera (Bausch + Lomb) lends itself well to mix-and-match approaches since it’s typically placed in only one eye. Dr. Shultz says the Apthera is a good option for “patients who want to have extended range of vision but can’t necessarily afford having technology in both eyes. One of the nice things with the Apthera lens is being able to provide depth of field without compromising distance significantly, certainly during the daytime.” He says patients who have the Apthera lens in one eye “still wind up with excellent distance vision and an enhanced range of vision” in that eye.

“Sometimes patients have corneal pathology, whether it’s a scar from previous pterygium excision or something else, or irregular astigmatism, and though this may be slightly off-label for the technology, using the Apthera lens to help reduce the visual aberrations associated with those problems is another reason for mixing and matching,” he says.

When Dr. Shultz uses the Apthera, he says he usually implants a monofocal spherical, monofocal toric or distance plus lens in the other eye. “I’ve used Eyhance (Johnson & Johnson Vision) lenses in the other eye,” he says. “Now we have access to the Aspire (Bausch + Lomb) monofocal as well for maximizing range of vision. Those two lenses offer a kind of slight distance plus, and then we can get a little bit more out of the Apthera or stick with a straight monofocal, depending on what the issues are.”

Dr. Shultz says he’s also had success using an Apthera and a Light-Adjustable Lens mix-and-match combination in certain patients with mild or forme fruste keratoconus. “I use the Light-Adjustable Lens to maximize the vision in the eye [with milder disease] and in the eye that may have more advanced keratoconus or more than a diopter and a half of manifest cylinder refraction, I’ll use the Apthera with the Light-Adjustable Lens to maximize the astigmatic treatment and also reduce the aberrations from the keratoconus.”

Dr. Donaldson says the Apthera/Light-Adjustable Lens combination is also good for patients with aberrated eyes, such as post-LASIK or post-RK. “A Light-Adjustable Lens in the dominant eye (targeted for distance) and an Apthera lens in the non-dominant eye (targeted at -0.75),” is another useful combination, she says.

Dr. Shultz agrees that post-RK patients are sometimes good candidates for a mix-and-match approach with the Apthera. “If they’ve had more than an eight-cut RK, they tend to have lots of peripheral aberrations that don’t do well with any IOL technology, so this is another area we’ve started using the Apthera, at least in one eye,” he explains. “Sometimes we’ll use it in both eyes, depending on the outcome of the first eye and how satisfied the patient is with both the quality of vision and the potential issues with their night vision.”

Pearls for Success

Here are some points to keep in mind when mixing and matching IOLs:

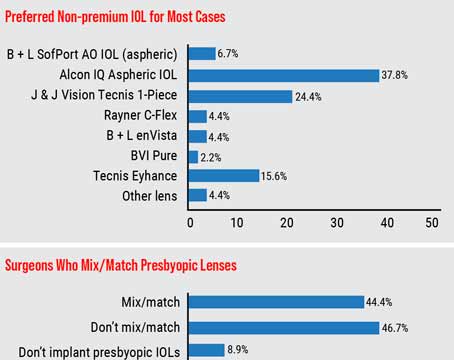

|

| A Symfony IOL in the dominant eye can provide good distance and intermediate vision in mix-and-match approaches, surgeons say. (Courtesy Johnson & Johnson Vision) |

• Check for previous experience with monovision. If a patient has previously had monovision in contact lenses, they’re likely a good candidate for a mix-and-match approach because they’ve already demonstrated neuroadaptability.

Dr. Dewey says, “One of my favorite combinations for these patients is an Eyhance in the dominant eye for distance and a Symfony in the non-dominant eye targeted anywhere from -0.75 D to -1.25 D, depending on the height of the individual and their previous myopic refraction. I employ this specific option for patients who’ve been monovision contact lens wearers. If they drove at night with a nearsighted contact lens in their non-dominant eye, they were dealing with glare and halos. With this mix-and-match approach, they’ll still have glare and halos in the non-dominant eye, but they’re pre-adapted to it. It gives them something they didn’t have before, because a lot of these monovision patients were wearing glasses for intermediate distance, so when you give them the enhanced depth with the Symfony, they’re ecstatic.”

This form of augmented monovision also solves a bigger issue—that of anisometropia. “Most of these patients are in the 24/40 range at distance, so they achieve the -2.50 effect at near, with only 1.25 D of anisometropia. It’s very well tolerated,” Dr. Dewey says.

• Perform a careful evaluation and get consistent measurements. Myriad factors can impact a lens plan, so conducting a careful evaluation of the visual pathway and the ocular surface is always necessary. “We have to be realistic about what patients and their eyes can tolerate,” Dr. Shultz says, noting that dilating the patient and evaluating for dry eye is key. “Fluorescein staining without any anesthetic is critical for looking at the ocular surface before surgery to evaluate candidacy for certain technology and how we’re going to optimize vision.”

“I like to have consistent keratometry, topography and astigmatism measurements on two different machines,” Dr. Farid says. “Regardless of the type of lens I put in, I want to make sure I nail the refractive outcome in each eye. I like to use the newer generation formulas such as the Barrett Universal formula to ensure I’m hitting my targets.”

|

| The Synergy IOL (above) is often paired with the Symfony to provide reading vision. (Courtesy Johnson & Johnson Vision) |

For multifocal lenses, such as PanOptix, Dr. Donaldson says she generally targets first plus. “For monofocal plus lenses such as the Eyhance or Rayner EMV, I target first plus in the dominant eye and second minus in the non-dominant eye to extend the range of vision,” she explains. “I find these targets to be similar for the Light-Adjustable Lens as a starting point, but then tend to dial up the near closer to a -1 D in the non-dominant eye to achieve optimal range without loss of distance.”

• Set realistic expectations. As with any premium lens technology, experts say it’s important that patients understand the limitations of their own vision compared with that of their friends, as well as the limitations of the technology. “We have to explain upfront what the potential risk factors are in their case if they’re not a great candidate for the same technologies as their friends or family,” Dr. Shultz notes.

“From the outset, patients should be advised that cataract surgery is a process involving two eyes,” Dr. Donaldson says. “We tell them that the two eyes work together to fill in gaps and to give us a more complete range of vision. Starting with the non-dominant eye helps assess the dysphotopsia profile for an individual patient—the non-dominant eye tends to be a bit more forgiving of side effects. Also, always remember to be honest with the patient and discuss potential compromises and limitations before surgery in order to set reasonable expectations.”

“I make sure that every patient understands the potential refractive issues we may be encountering, such as how conditions such as keratoconus or previous refractive surgery are going to affect the outcome,” Dr. Dewey says. “If you explain to patients the limitations on the choices they’re making, they better understand why things aren’t as sharp and crisp as they’d like. Patients going through the premium lens channel have higher expectations, so for them this is a given. Patients not going through the premium channel deserve to know what the likely outcome of their surgery is going to be every bit as much [as premium-channel patients].

“It amazes me that even when you’ve got all the bases covered as well as you possibly can, patients are still going to find ways to end up needing task glasses,” he continues. “One cautionary tale is to emphasize to that -4 myope who wants amazing clarity throughout all ranges that their near vision with our current technologies is going to stop at about 12 inches close to their nose, as opposed to eight. So, for some patients who are really accustomed to being able to take their contacts out or glasses off and just hold things right under their nose and see them, you just have to point out that this will put them back to where their bifocals had them. If they want to hold things closer, they’ll need some supplemental magnification.”

|

| Surgeons say the small-aperture Apthera (left) can be mixed with monofocals such as Aspire (right) and enhanced monofocals such as Eyhance and the Light-Adjustable Lens to improve the range of vision in certain patients. (Courtesy Bausch +Lomb) |

• Determine true eye dominance. “It’s really important to determine the proper dominant and non-dominant eye in the patient,” Dr. Zhu says. “We typically check eye dominance by having the patient hold up their hands to create a circle, and then with both eyes open, they’ll place a distance target within that circle, then close each eye. Whichever eye maintains that distance target within the circle is typically the dominant eye, or distance eye, and you’d place the monofocal or EDOF in that eye. The other eye would be the non-dominant eye or near eye, and you’d place the full-range vision (e.g. trifocal or multifocal) lens in that eye.

“However, in my experience, about 20 to 25 percent of patients don’t follow that rule, meaning that even though the test might show the left eye as dominant, the patient actually prefers that eye as their ‘near’ or ‘reading’ eye—meaning that they prefer the multifocal in their left eye, which is the opposite of what you might think,” she continues. “So, I don’t rely solely on that test for some patients. I often have my in-house optometrist double check the ‘true dominance’ by placing a loose lens over each eye. Basically, I correct both eyes with the patient’s manifest refraction and then I place a +2 loose lens first over the left eye and then over the right eye. In both situations, I tell the patient: ‘This loose lens is going to make the distance vision look worse. But over which eye is the distance vision a little bit less blurry, or over which eye is it more clear?’ I document whichever eye the patient preferred the add over (i.e., felt less blurry), and that becomes the true non-dominant eye or near eye, in which you’d place the full-range presbyopia correcting lens.”

Dr. Zhu says she doesn’t use this approach with every patient, as it’s not always necessary and can be more time-consuming, but finds it helpful in patients whose eye dominance seems to switch back and forth from one eye to the other; in patients who have a similar refractive error in both eyes; or in patients where the eye dominance appears to be the opposite of expectations. “For example, I’d generally expect the shorter eye to be the non-dominant eye in a hyperope, and I’d expect the longer eye to be the non-dominant eye in a myope,” she says. “If that doesn’t correlate with the initial eye dominance test where they hold out their hands, then I’ll definitely have the OD double check by doing the loose-lens trial. Oftentimes, the loose-lens trial will confirm the opposite dominance of what was initially obtained and align with what I would have expected based on the refractive error or axial length.”

• First eyes first. Waiting and assessing the first-eye outcome before operating on the second eye creates more opportunity for better-informed lens selection, surgeons say. “When possible, I prefer to start with the non-dominant eye, particularly when implanting a multifocal or EDOF lens,” Dr. Donaldson says. “This gives us an opportunity to assess any potential dysphotopsias. If the patient notices the dysphotopsias and is significantly bothered by them, I’ll combine this with a monofocal or EDOF lens in the dominant eye—for example, a PanOptix in the non-dominant eye and an EDOF lens (such as the Vivity or Synergy) or monofocal plus distance lens in the dominant eye, targeted for distance (such as the Eyhance or the Rayner EMV).”

“My preference is typically, when possible, to operate on the dominant eye first, so that I can really assess whether or not the non-dominant eye is going to get the same technology or if we need to use a secondary technology, depending on the outcome of the first eye,” says Dr. Shultz.

Dr. Dewey agrees with the sequential approach, saying he doesn’t perform bilateral simultaneous cataract surgery. “My surgeries are usually two weeks apart, or more if the patient prefers,” he explains. “As much as I love the enthusiasm about bilateral simultaneous, when the patient is going to be living with the result for the rest of their life, and I can give them a better result by tailoring their second surgical result to meet the needs that we’re working to achieve by reviewing their first surgical result, I think two weeks out of a lifetime is probably worthwhile.”

Laying out the steps of the mix-and-match process is helpful for patients. Dr. Farid says, “When I’m talking to patients, I let them know what I’m planning to do. I tell patients, ‘Let’s do the first eye with the lens I think is going to be ideal for this eye.’ We start with that. And then I say, ‘Before we do the second eye, we’re going to have a conversation to see how you’re doing with the first eye and to then use your second eye to fill in gaps.’ Those are the words I use so that patients realize we’re really personalizing their vision. We’re taking our time even between the two eyes to find out where we landed with the first eye before we finalize our decision on the second eye. Patients really like that because they’re playing an active role in their final lens decision.”

Dr. Farid is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision, Bausch + Lomb and Alcon. Dr. Zhu is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision, Bausch + Lomb, LensTec and Alcon. She also receives research grants from Alcon. Dr. Shultz is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision and a consultant and investigator for Bausch + Lomb. He has an investigative contract with RxSight. Dr. Dewey is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Donaldson is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision, Bausch + Lomb, Alcon and Zeiss.

.png)