Presentation

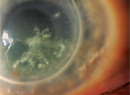

A 42-year-old black male presented to the Wills Eye Emergency Room complaining of a stye on the right upper lid for three months. He noted mild itching of the lid with minimal tenderness. He attempted frequent warm compresses with no improvement. Three weeks prior to presentation he squeezed the lid with clear discharge and no pus. He had no change in his visual acuity, but the lesion had enlarged to obscure his visual axis (See Figure 1a and 1b). The patient reported no diplopia, pain, previous surgery, trauma, fevers or chills. He reported no past ocular history.

Medical History

The patient reported a history of hypertension controlled without medication. The patient reported no smoking, alcohol or illicit drug use history. He traveled frequently for work. Review of symptoms was otherwise negative.

Examination

His ocular examination revealed a visual acuity of 20/40 OD and 20/30 OS. His pupils, ocular motility and visual fields to confrontation were normal. Intraocular pressures were 13 mmHg OU. External exam of the right upper lid showed extensive violaceous edema with multiple chalazia-like lesions and madarosis. The lesion was non-tender to palpation and firm. Blepharitis was noted on both eyelids. Slit-lamp examination revealed no additional findings. Dilated fundus exam was normal OU.

Diagnosis, Workup and Treatment

The differential diagnosis for this eyelid lesion is broad, and can best be approached as infectious, inflammatory or neoplastic. Although the chronicity of the lesion argued against an acute infectious process, the patient was initially started on Augmentin and warm compresses, and referred to Oculoplastics for chalazion excision and biopsy. The patient presented to Wills Eye two weeks later having finished his course of Augmentin. The lesion had continued to enlarge, but remained painless. He noted that it had softened. A cellulitic process seemed less likely. A chalazion excision was performed with tarsal biopsy. A large cystic area was incised with only minimal purulent material. Significant bleeding occurred during the procedure and hemostasis was difficult to maintain. The patient was started on topical antibiotic/steroid ointment after the excision.

Two weeks after the initial excision and biopsy, the patient had no improvement in symptoms. The pathology sample showed evidence of scarring with hemosiderin deposition, but no evidence of malignancy. However, the atypical clinical picture along with poor response to antibiotic and anti-inflammatory treatment prompted a more extensive biopsy. This biopsy was taken from an external lid crease approach. It was again noted during the procedure that hemostasis was difficult to maintain, and a vascular tumor was suspected. No purulent material was noted. The repeat biopsy revealed a spindle cell vascular tumor with hemosiderin, as well as CD34 positivity (See Figure 2). This was highly suspicious for Kaposi's sarcoma, and further testing revealed positive staining for HHV8 (See Figure 3).

Upon further questioning, the patient had a history of intercourse with men. HIV testing was positive, and the patient was referred for initiation of HAART therapy. At the time of this case report, the patient had started HAART therapy but was lost to follow-up with his primary-care physician.

Discussion

Kaposi's sarcoma is a highly vascularized, mesenchymal tumor that clinically presents as a circular, violaceous skin lesion. It has irregular borders that may be located above the epidermis or subdermally. KS is associated with human herpesvirus-8, and the color of the lesion varies from a deep red to purple. The tumor may present early as a firm palpable mass, but as time progresses, KS lesions can soften. KS initially presents on the distal extremities, eyelids and conjunctiva. As the disease progresses, lesions can develop on the torso.

Ocular manifestations of KS are commonly localized to the anterior segment of globe and the ocular adnexa. Ocular adnexal KS is divided into three stages. Stages I and II are flat and clinically visible for approximately four months after which they commonly disappear due to the action of several inflammatory cytokines that induce apoptosis. Stage III lesions are more elevated and have a nodular appearance that persists for longer than four months.

There are four subgroups of KS, including classic, African, iatrogenic and HIV-related. Classic KS occurs in healthy, middle-aged males from Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean and equatorial

The introduction of HAART has drastically changed the landscape of KS. The prevalence of KS has decreased from 40 percent to 20 percent, with an increase in one-year survival from 59 percent to 79 percent. There is a significant clinical response in 60 percent of patients with KS on HAART alone. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor regimens and protease inhibitor regimens are equally effective. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome has been described after initiation of HAART with a decline in clinical status. Other forms of therapy have been introduced with variable success, including local radiation, excision, cryotherapy and chemotherapy.

Early diagnosis and control of HIV/AIDS is critical in prolonging life expectancy and reducing opportunistic infections. Ophthalmologists can play a role in early diagnosis of HIV by recognizing the ocular manifestations of a patient with Kaposi's sarcoma.

The authors would like to thank Jacqueline Carrasco, MD, and Ralph Eagle, MD, for their assistance with this case.

1. Sezer N, Erqikan C. Kaposi's Sarcoma with Ocular Manifestations. Brit. J. Ophthal 1964;48,223.

2. Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, Jaff HW. Kaposi's Sarcoma among persons with AIDS: A sexually transmitted infection? Lancet 1990 Jan 20;335(8682):123-8.

3. Rao NA. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and its ocular complications. Indian Journal of Ophthal 1994;42:51-63.

4. Cunningham ET, Margolis TP. Ocular Manifestations of HIV Infection.

5. McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran, D. HIV Infection in the

6. Stürzl M, Hohenadl C, Zietz C, Castanos-Velez E, Wunderlich A, Ascherl G, Biberfeld P, Monini P, Browning PJ, Ensoli B. Expression of K13/v-FLIP Gene of Human Herpesvirus 8 and Apoptosis in Kaposi's Sarcoma Spindle Cells. JNCI 1999;91(20):1725-1733.

7. Freedberg KA, Losina E, Weinstein MC, Paltiel AD, Cohen CJ, Seage GR, Craven DE, Zhang H, Kimmel AD, Goldie SJ. The Cost Effectiveness of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Disease. N Engl J Med 2001;344:824-831.