According to the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II, “dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”1

Many therapeutic strategies currently on the market have been used to manage dry-eye disease. In recent years, though, new regenerative therapies have provided a new perspective for managing this complex condition.2

“We’ve learned a huge amount about the disease during the past 10 to 15 years,” says Michael A. Lemp, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at Georgetown University. “However, it’s still very confusing for a lot of doctors. Because there’s been so much research done in different areas, ophthalmologists are really not clear on how to apply it.”

The first step toward a potential cure is understanding the disease process. “Many people believe that inflammation is the principal mechanism at work in dry-eye disease,” Dr. Lemp says. “I’m not one of those people, but there are a number of papers indicating that dry eye is an inflammatory disease. While it is an inflammatory disease in a lot of people, inflammation isn’t present in a lot of others. So, when it’s there, and it is there in most moderate to severe cases, it is an attractive target to deal with. The whole inflammatory process in the body is complicated, which makes it a great area for research because there are many entry points. This means that there are many opportunities to interfere with those entry points and decrease inflammation. In short, anti-inflammatories are very useful for patients with moderate to severe disease.”

According to Dr. Lemp, researchers are finding out more about the epigenesis of the disease. “We don’t know what the initiating factor is, and it’s probably not the same in all people, he says. “In other words, the development of dry eye as a disease probably started out in different ways in different people. Each person has some type of proclivity for developing it. If a patient has a systemic disease that has an inflammatory component, the inflammatory state can include the lacrimal glands. They’re affected by inflammatory cells, which damage tissue and tear production. These are some of the patients who have the most severe form of the disease, which is probably less than 10 percent of the dry-eye population.”

Understanding Dry Eye

According to Dr. Lemp, most patients develop dry eye over time. “There are two basic subtypes of the disease. One is aqueous tear-deficient dry eye, and the other is evaporative dry eye, where the tears evaporate abnormally rapidly. The latter can be a result of meibomian gland dysfunction or other ocular surface or lid problems,” he explains.

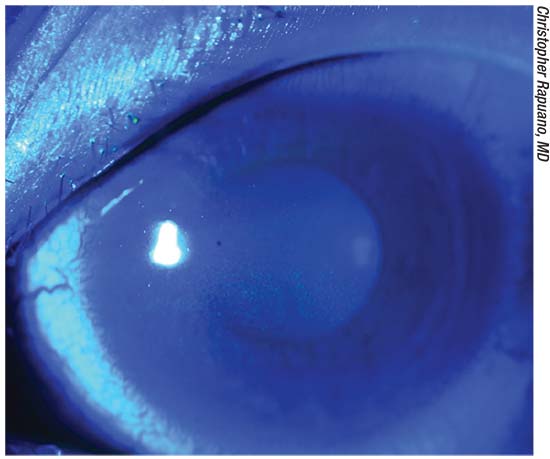

|

| Fluorescein staining with the cobalt blue light demonstrating superficial punctate keratopathy related to dry eyes. |

Dr. Lemp adds that patients who have moderate to severe dry eye almost inevitably have both types. “For example, if a patient has meibomian gland dysfunction, in which he or she is not producing enough of the right kind of oil, and water is evaporating from the tear film, the patient will get a concentrated tear film,” he says. “That drives up tear osmolarity and signals the lacrimal glands to start producing more tears. So, it’s thought that the glands react as a compensatory mechanism. Then, what initially starts off as a compensatory process may actually worsen the disease if it continues. Many doctors continue to treat meibomian gland dysfunction as a separate disease, when it’s actually the most common subtype of dry eye. It’s been reported that 65 to 70 percent of dry-eye patients have evaporative dry eye. It should be noted, however, that early onset of meibomian gland dysfunction may not present itself as classical dry-eye disease.”

Patients with evaporative dry eye have extremely concentrated tears, which can negatively affect the ocular surface. “Tear osmolarity is one way of demonstrating that concentration,” Dr. Lemp notes. However, as measured in a laboratory test, it requires a significant sample of tears, which most dry-eye patients don’t have. In 2008 or 2009, TearLab brought in-office tear osmolarity technology to the market. And, it turned out to be quite accurate. We conducted a 300-patient test, and it performed better than seven other tests that we evaluated. Tear osmolarity was the best identifier of dry eye. However, there was a lot of variability in dry-eye patients.”

Ophthalmologists were concerned that the test was not repeatable, but it was only not repeatable in dry-eye patients. It was then found that tear-film instability, reflected in the nonrepeatable results, is actually a marker for dry eye. “After dry-eye patients are treated effectively with an anti-inflammatory or other drug, the tear osmolarity variability disappears,” Dr. Lemp explains.

Tear-film instability is typically measured by tear-film breakup time, which is highly subjective. “You’ve got to look for the first spot that breaks up in the tear film after a blink, and you might miss it. That’s why it’s difficult to get reproducible results. Fortunately, OCT products that are currently on the market can show pictures of the tear film breaking up. You can program these machines to do that, and you can get an accurate picture of how long it takes from a blink to the first breakup of the tear film. This technology has just become available in the past two years,” Dr. Lemp continues.

Additionally, a very small group of people suffer from a very severe form of ocular pain that is similar to dry-eye disease. “No matter what surface medications you treat them with, they remain in almost unbearable pain. We now know that it is a central nervous system problem in which some of the impulses that are going in from the eye are becoming misdirected on a different pathway that has been built up in the central nervous system. It’s detached from what’s actually happening on the ocular surface, and treatment should be directed to the central nervous system,” Dr. Lemp says.

According to Stephen Pflugfelder, MD, director of the Ocular Surface Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, if ophthalmologists hope to eventually cure dry eye, they need to be better at diagnosing and classifying the condition based on the underlying problem. “Unfortunately, I don’t think we do a good job of this right now,” he says. “This involves determining which glands are not functioning well and then maybe using targeted therapies, either medications, surgical therapies, or cell-based therapies, to try to treat that. This could involve the meibomian glands, the conjunctival goblet cells or the lacrimal glands.”

Conventional Treatments

Treatment of dry eye has traditionally been focused on treating the symptoms, and is mostly based on lubrication and the control of inflammation. However, Dr. Lemp explains that anti-inflammatories haven’t been wholly successful. Some people respond well to them, while others don’t. “Cyclosporine [Restasis, Allergan] was the first one that came on the market, and researchers looked at whether treatment with cyclosporine could increase tear production,” he recounts. “They found a statistically significant improvement in 15 percent of the people in the study, as opposed to 5 percent of the people who received placebo. A 15 percent improvement rate is not terribly impressive, but it was statistically significant, and that’s why the Food and Drug Administration approved it,” he says.

Dr. Lemp adds that ophthalmologists and patients are thankful for these anti-inflammatories, but that they’re not as effective as some had hoped.

Dr. Pflugfelder agrees. “Cyclosporine has the unique property of actually increasing the number of mucus-producing goblet cells,” he says. “So, in some ways, it addresses the underlying problem. However, that’s only beneficial in people who have a goblet-cell deficiency to begin with. In the future, having better diagnostic tests to differentiate between a lipid deficiency and a mucus deficiency or specific deficiencies in tear components would be very valuable.”

“This has led people to look at other treatment possibilities,” Dr. Lemp adds. Allergan, for example, has developed TrueTear, which stimulates tear production by stimulating the nasal mucosa, a type of reflex tearing,”

New Treatment Strategies

The latest research is focused on the development of new biological strategies, with the goals of preventing disease progression, regenerating affected tissues and maintaining corneal transparency.2 New treatments include growth factors and cytokines, as well as using different cell sources—specifically mesenchymal stem cells.

|

| Researchers say most dry eye consists of a combination of aqueous deficiency and meibomian gland dysfunction (above). |

An important advance in the management of severe cases that don’t respond to conventional therapy is the use of drops of different blood products. The most common choices are the use of autologous or allogeneic serum drops, platelet-derived plasma products and umbilical cord blood serum.2

“Autologous serum tears are gaining popularity. They use the patient’s own antibodies and growth factors to combat dry eye,” says Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, chief of the Wills Eye Cornea Service in Philadelphia. “However, the downsides are that the patient has to get his or her blood drawn, it’s expensive and it’s often not covered by insurance. There are a few companies that are researching immune components. Some companies are looking at amniotic membrane components, and some are looking at other components. As we learn more about the immune system related to dry eye, better immune treatments will be developed. Cyclosporine is an immune modulator, but it’s broad-spectrum. In the future, I think we’re going to be able to target it better.”

Autologous serum was first successfully used in patients with dry eye in 1984, and it gained widespread acceptance as an adjuvant therapy in different ocular-surface disorders in 1999. It helps to lubricate the eye, and also performs anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and epitheliotrophic functions through certain biomolecules that are similar in composition to natural tears.2 Patients can use autologous serum as often as hourly.

Allogeneic serum from healthy blood donors can be used if a patient’s own serum is unavailable. Additionally, platelet-rich plasma products have successfully treated cases of severe dry eye that didn’t respond to conventional therapy.2 Umbilical cord blood serum (recommended for use at a 20-percent concentration instilled four to six times per day2) also contains a high concentration of tear components. In one study, umbilical cord serum eye drops decreased symptoms and increased goblet-cell density in severe dry-eye syndrome more effectively than autologous serum drops.2

Stem-cell Therapy

During the past decade, there’s been an increasing interest in using stem-cell therapy to treat a number of different pathologies, including ocular diseases.

Mesenchymal stem cells have been proposed as cell therapy for many diseases with an inflammatory and immunomediated component. Mesenchymal stem-cell therapy in experimental dry-eye syndrome models was found to improve tear volume and tear-film stability, increasing epithelial recovery and the number of goblet cells and decreasing the number of meibomian gland injuries in the conjunctiva.2

“I think stem cells could be helpful for regenerating the meibomian or lacrimal glands,” Dr. Pflugfelder says. “Let’s say you could inject stem cells into the lacrimal gland, and they would make it secrete again. Animal studies have shown that lacrimal-gland stem cells or mesenchymal stem cells may work. Another option would be to use the stem cells that are already present and stimulate them to start regenerating the tissue.”

Another potential treatment that’s in the early stage of research is lubricin, which is a protein in the tear film that facilitates the lubrication between the lid and the surface of the eye as you blink. It’s the same protein that’s present in joints to provide lubrication. “Lubricin is thought to be decreased in dry eye, and there is now a manufactured protein (ECF843 by Novartis) that is identical to it, which is being used in orthopedics and is in early stages of development for dry-eye disease,” Dr. Lemp explains.

Low-dose corticosteroid drops are also being investigated for the treatment of dry eye. “None of those treatments are being touted as a cure for dry eye, however,” Dr. Rapuano says. He adds that, as researchers learn more about the mechanisms of dry eye, physicians will have better targeted therapies. “As we treat conditions such as conjunctivochalasis better and look for other disorders, including superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis and floppy eyelids, we’ll improve our treatment of problems that fall under this huge umbrella of ‘dry eye.’ Certainly, we would love to have an anti-inflammatory medication that works better than cyclosporine and lifitegrast with very few side effects, and we’d love a nice strong steroid without the steroid side effects. Currently, those don’t exist,” Dr. Rapuano says.

Dr. Pflugfelder says he is hopeful for a cure. “I hope there will be a cure for dry eye, but I’m not sure it’s going to happen immediately,” he says. “It’s probably going to take a while, because cell-based therapies, such as stem-cell treatments, are complex. But, I do think it will eventually happen.” REVIEW

Dr. Lemp has served as a consultant to TearLab and Santen. Dr. Pflugfelder is a consultant to and receives research funding from Allergan. Dr. Rapuano is a consultant to and/or lecturer for Allergan, Bio-Tissue, Kala, Shire, Sun Ophthalmics and TearLab.

1. Winebrake JP, Drinkwater OJ, Brissette AR, Starr CE. The TFOS Dry Eye Workshop II: Key Updates. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2017.

2. Villatoro AJ, Fernandez V, Claros S, et al. Regenerative therapies in dry eye disease: From growth factors to cell therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017;18:11:2,264.